This policy brief is based on BOFIT Discussion Papers 7/2025. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Bank branches hold locally acquired “soft” information about borrowers, raising the question of whether such information can be transmitted effectively across units. Using the universe of corporate loans issued by a major commercial bank in a decade, we find that when firms switch branches within the same bank, their new loans carry significantly lower spreads. Yet these benefits fade: within a year, loan spreads revert to market levels and eventually exceed them, revealing a clear pattern of intra-bank hold-up. These findings demonstrate that organizational frictions within banks materially distort lending outcomes, linking relationship lending to broader theories of delegation, coordination, and imperfect information transmission inside firms.

Relationship lending is traditionally viewed as creating informational advantages for banks, enabling better credit assessment but also potentially raising switching costs for borrowers. Most prior research analyses switching across banks. However, large banking groups operate extensive branch networks, raising a fundamental but understudied question: What happens when firms switch within the same bank, that is, moving their borrowing from one branch to another? At first glance, one might expect switching within the same banking institution to be seamless: branches share internal information systems, operate under common ownership, and should have aligned reputational and risk-management incentives. Under this view, the transfer of borrower information should be nearly frictionless, implying little room for pricing differences or hold-up behavior.

However, insights from organizational theory offer a contrasting perspective. Dessein (2002) shows that even within firms, the transmission of “soft” information is inherently strategic and imperfect, creating a fundamental tension between centralized control and effective use of private information. Similarly, Alonso et al. (2008) argue that decentralized units may fail to coordinate efficiently unless private information can be credibly communicated, while Stein (2002) highlights how hierarchical structures can impede the flow of information from local offices to higher-level decision makers. Applied to banking, these theories suggest that branch-level autonomy in customer management, pricing, and loan approval can generate organizational frictions that hinder information sharing across branches, despite shared systems and formal integration. In this setting, switching within a bank becomes an economically meaningful event rather than a trivial administrative transfer. By leveraging the population of a decade of branch-level loan origination data, the study provides new evidence on this overlooked margin of credit market competition.

To study switching within a bank, the study distinguishes branches by their recent lending history with each firm following Ioannidou and Ongena (2010). A branch that has extended credit within the previous twelve months is classified as an “inside branch,” reflecting an ongoing lending relationship. By contrast, a branch that has not lent to the firm during that period is deemed an “outside branch.” When a firm receives a new loan from an outside branch, that loan is labeled a “switching loan,” signaling that the borrower has shifted its primary lending relationship within the same banking organization.

Applying this definition yields 7,628 switching loans, representing 7% of all loan originations. About 22% of firms switched branches at least once over the decade, implying an annual switching rate of 2.2%. This is lower than the 4-4.5% annual bank-switching rates seen in prior research, which is intuitive: switching within a bank is less costly and operationally simpler than switching to a new bank, yet information frictions may still discourage firms from switching unless they anticipate tangible gains.

Using a double matching approach, comparing switching loans to similar non-switching loans issued by either inside or outside branches in the same month, the study uncovers pronounced dynamics in how borrowing costs evolve around a switch. Initially, firms that move from their incumbent inside branch to a new outside branch obtain loans with interest rate spreads about 6 basis points lower than those paid by comparable existing customers. Although modest in absolute terms, this reduction is meaningful: it represents roughly 1% of the average loan rate and 7% of the average loan spread, confirming that switching delivers an immediate and economically relevant price advantage.

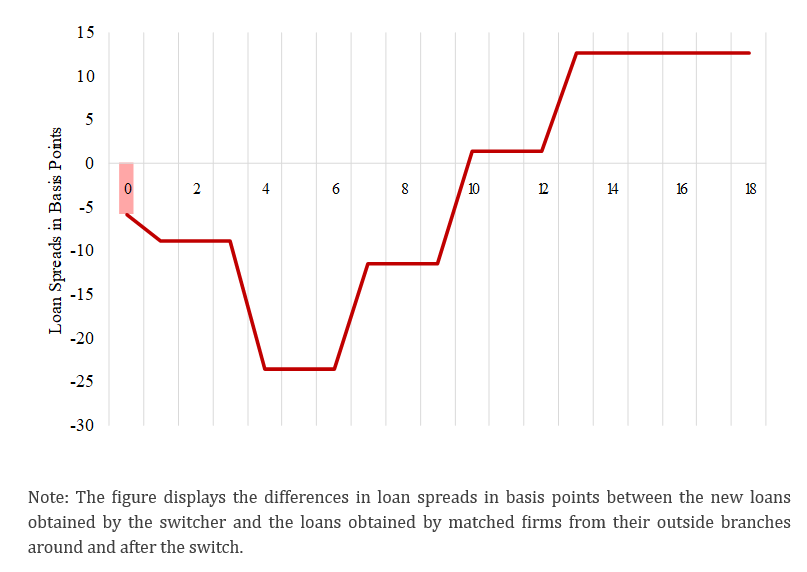

These initial pricing benefits do not remain static, as shown in Figure 1. The spread discount deepens by an additional 18 basis points over the first two quarters following the switch, indicating that outside branches engage in particularly aggressive pricing during the early phase of the new relationship. Such introductory discounts are consistent with branch-level incentives to expand client portfolios and demonstrate competitive behavior even within the boundaries of a single banking institution. Yet these advantages gradually dissipate. Within about a year, switching firms’ loan spreads converge back to the average borrowing cost, and eventually even rise above it. This rise-and-revert cycle indicates that once the outside branch develops sufficient borrower-specific knowledge, it leverages this informational advantage to extract rents, effectively becoming a new incumbent. Such dynamics imply that soft information does not flow seamlessly across branches. Instead, intra-bank organizational frictions meaningfully constrain information transmission, causing each branch to rebuild its own information set and adjust prices accordingly. These dynamics reinforce the broader conclusion that, even within a single bank, loan pricing is shaped by localized incentives, limited internal coordination, and incomplete sharing of relationship-specific information, leading to intra-bank hold-up.

Figure 1. Loan spread differences after switching

A series of additional analyses provides further support for intra-bank hold-up. First, we investigate cases where branch managers move together with the borrower to the new branch. In such scenarios, the usual spread discount associated with switching disappears entirely. This pattern is consistent with the idea that the manager carries soft information that would otherwise be lost during the switch; when this information travels with the borrower, the new branch no longer needs to compensate for informational gaps, and the hold-up dissipates.

Second, we examine the role of geography and find that switching costs are smaller when borrowers switch to nearby branches. This suggests that local competition constrains the pricing power of incumbent branches, mitigating their ability to charge informational rents. Third, switching to newly established branches leads to markedly larger reductions in spreads around 27 basis points. New branches, facing minimal entrenched clientele and eager to expand their portfolios, appear especially aggressive in offering introductory discounts. These results indicate that hold-up is strongest when incumbent branches face limited competitive pressure and that the scope for internal competition varies across the bank’s branch network.

Fourth, we exploit the staggered rollout of China’s Social Credit System (SCS) as a natural experiment in information disclosure. After the introduction of SCS, firms experienced substantially lower hold-up costs when switching, suggesting that enhanced transparency reduced the informational advantages historically held by incumbent branches. Finally, we show that deeper FinTech adoption similarly weakens hold-up by converting traditionally soft, relationship-based information into hard, verifiable data. By improving data accessibility and standardizing information across branches, digital tools reduce asymmetries that typically underpin hold-up.

Intra-bank hold-up generates important distributional and welfare consequences. Because informational rents are largest where borrower transparency is weakest, smaller, privately owned, and financially constrained firms bear a disproportionate share of the cost. These firms rely heavily on relationship lending and have limited outside options, making them more vulnerable to rent extraction once a branch accumulates soft information. In contrast, large firms and state-owned enterprises, who benefit from better disclosure, diversified funding sources, and institutional advantages, experience significantly weaker hold-up effects. This uneven burden amplifies existing credit access disparities and raises borrowing costs precisely for the firms that are most dependent on bank financing for growth.

As a result, such strategic rent extraction produces a clear trade-off at the branch level. Branches that exploit their informational advantage succeed in screening out weaker borrowers and reducing non-performing loans, improving the quality of their credit portfolio. Yet these gains come at the expense of scale, market share, and inclusivity. Higher spreads accelerate borrower attrition among cost-sensitive firms, reducing the breadth of lending relationships and weakening long-run franchise value. In effect, hold-up strategies strengthen branch-level credit risk profiles while diminishing allocative efficiency and limiting access to finance. This pattern highlights how internal organizational incentives, shaped by performance metrics, delegation structures, and information silos, can materially influence credit market outcomes.

Taken together, these findings show that intra-bank hold-up is not merely a pricing phenomenon but a structural friction with aggregate implications. By pushing vulnerable firms toward more costly financing and constraining borrower mobility, internal informational frictions reduce the efficiency with which credit is allocated across the economy. The resulting distortions echo classic predictions from organizational economics: when local managers retain private information and internal communication is imperfect, divisions behave like semi-autonomous units that maximize their own rents rather than overall organizational performance (Garicano, 2000). This underscores the broader policy relevance of improving information portability and aligning incentives within multi-branch banking organizations.

Alonso, R., Dessein, W., & Matouschek, N. (2008). When does coordination require centralization?. American Economic Review, 98(1), 145-179.

Dessein, W. (2002). Authority and communication in organizations. Review of Economic Studies, 69(4), 811-838.

Garicano, L. (2000). Hierarchies and the organization of knowledge in production. Journal of Political Economy, 108(5), 874-904.

Ioannidou, V., & Ongena, S. (2010). “Time for a change”: Loan conditions and bank behavior when firms switch banks. Journal of Finance, 65(5), 1847-1877.

Stein, J. C. (2002). Information production and capital allocation: Decentralized versus hierarchical firms. Journal of Finance, 57(5), 1891-922.