This policy brief is based on ECB Working Paper Series, No 3126. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Our study documents the central role of the foreign sector in the market for safety and explores its macroeconomic implications. Using new data for advanced economies since 1980, we show that foreign demand for safe assets has steadily increased, and that is has been mainly met by safe asset issuances of the domestic financial sector. Such issuances, however, are typically backed by risky loans, and thus the increases in foreign demand for safety may result in domestic credit booms that contribute to macroeconomic instability. The results highlight the importance of carefully managing the creation of safe assets within the global financial system.

Safe assets play a pivotal role in the modern economy. Broadly defined as financial assets with highly certain payments, they are a cornerstone of modern financial markets due to their unique ability to be reliable stores of value, act as collateral in transactions, help fulfil prudential requirements, and serve as key price benchmarks (Gourinchas and Jeanne, 2012).

In recent decades, the demand for safe assets has surged, particularly from emerging economies (Bernanke, 2005). This demand has been met by advanced economies, either through liabilities of the public sector (e.g., government bonds) or the financial sector (e.g., deposits and asset-backed securities). However, it is not clear whether advanced economies can sustainably supply safe assets abroad without jeopardising their own financial stability—especially when these assets are created by private financial institutions (Caballero, Farhi, and Gourinchas, 2017; Maggiori, 2017; Caballero and Simsek, 2020; Ahnert and Perotti, 2021). These challenges raise the question of how global demand for safety interacts with the domestic supply of safe assets, and what this implies for macro-financial stability.

In a recent study, Foreign Demand for Safety and Macroeconomic Instability (Castells-Jauregui, Kuvshinov, Richter, and Vanasco, 2025), we address these issues by analyzing the sectoral composition of safe-asset markets in 21 advanced economies since the 1980s. The study documents the central and growing role of foreign demand, the dominance of the domestic financial sector in meeting that demand, and the macroeconomic consequences of this interaction. The findings show that as foreign demand for safety rises, financial institutions respond by creating safe liabilities backed by risky loans, and that increases in foreign demand for safety are followed by lower medium-term GDP growth.

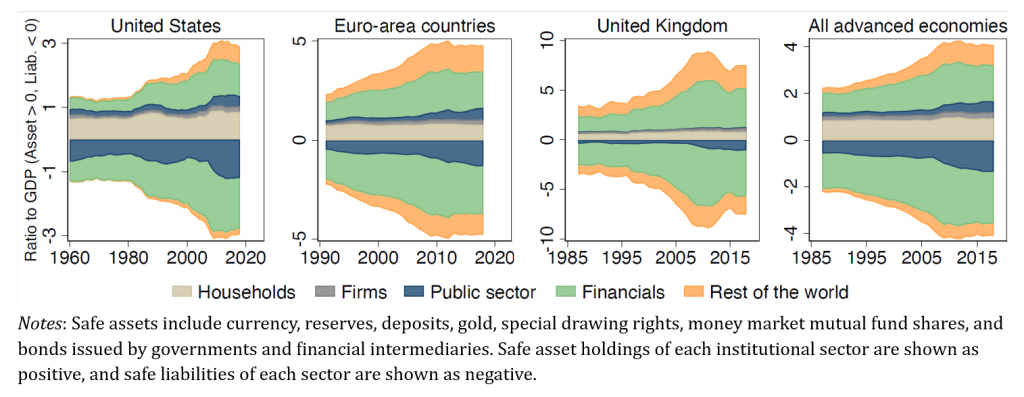

We start by analyzing which sectors are the dominant holders and issuers of safe assets. Figure 1 presents the evolution of gross safe-asset positions for the major economies in our sample, where safe-asset holdings appear as positive values and safe liabilities as negative values. The first takeaway is that safe-asset positions have expanded markedly relative to GDP, and that most of the growth in both holdings and liabilities has been driven by the financial and foreign sectors, pointing to increased safe-asset intermediation both within and across borders. More careful regression analysis in the paper further shows that the foreign and financial sectors are responsible for almost all fluctuations—i.e., issuances and acquisitions—of safe assets, confirming their dominance.

Figure 1. Gross safe asset positions of different institutional sectors

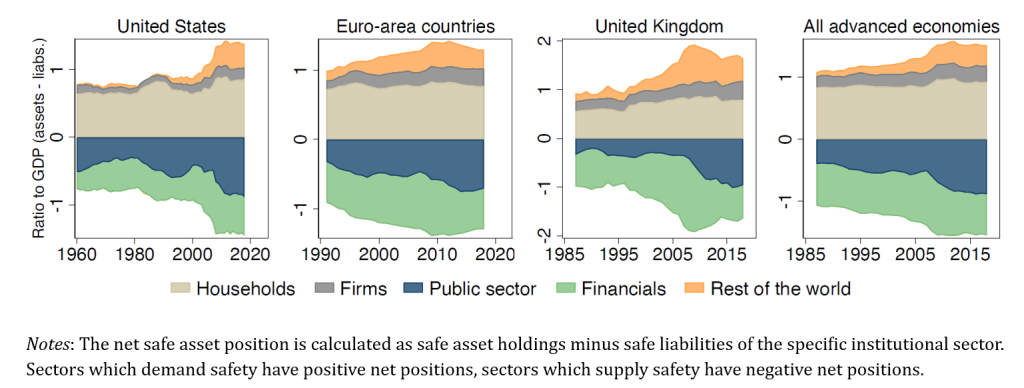

We then turn to net safe-asset positions—defined as the difference between safe assets and safe liabilities—which allows us to differentiate between safe-asset demand (positive net positions) and supply (negative net positions). Figure 2 shows that since 1980, the foreign sector has been increasing its net holdings of safe assets, meaning that the advanced economies in our sample have been increasingly exporting safety, both to each other and to the economies not in our sample (such as emerging markets). Increases in safe-asset supply were largely driven by domestic financial institutions before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–08, with a substitution toward public-sector safe assets after the GFC.

Figure 2. Net safe asset positions of different institutional sectors

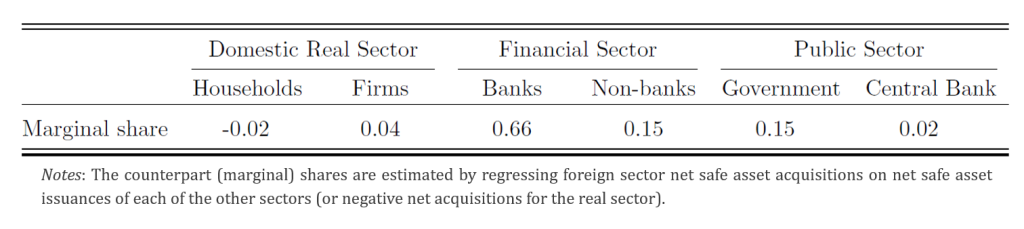

We document that domestic financial institutions are crucial for meeting increases in foreign demand for safe assets. A simple decomposition exercise shows that whenever the foreign sector acquires $1 extra of safe assets, 81 cents of this dollar is supplied by the domestic financial sector, with the remainder supplied by the public sector (see Table 1). These results continue to hold when we instrument foreign-sector acquisitions with a proxy for foreign demand for safety, exploiting variation in foreign reserve accumulation by Asian economies and the differential responses of the advanced economies in our sample to these shifts, building on Nakamura and Steinsson (2011).

Table 1. Counterparts to $1 of foreign sector net safe asset purchases

The interaction between foreign demand and private-sector supply of safe assets can create macroeconomic risks. When foreign investors seek more safe assets, domestic financial institutions often respond by creating them—typically backed by increased domestic lending. As a result, rising foreign demand can indirectly fuel household and corporate credit booms at home, with potentially adverse effects on the broader economy.

In the paper, we show that higher foreign safe-asset demand is associated with large increases in domestic risky credit: for every $1 of safe assets acquired by the foreign sector, the domestic financial sector increases its lending by 61 cents. Moreover, higher safe-asset demand from abroad, or higher safe-asset supply by domestic financial institutions, is followed by low medium-term real GDP growth.

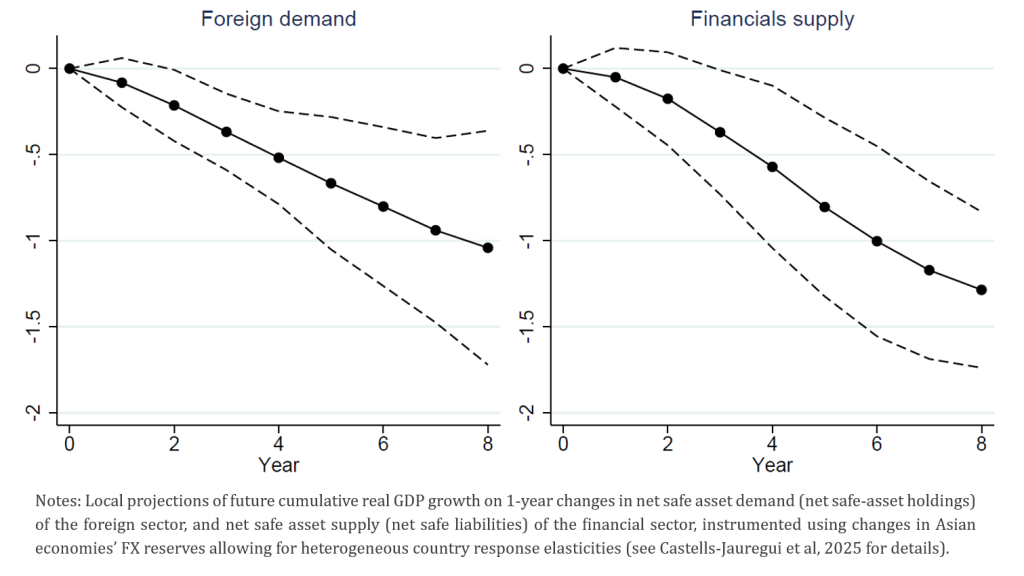

Figure 3 summarizes the estimated effects of increases in foreign demand for safe assets and in safe-asset supply by financial institutions on real GDP growth (using local projection methods and the instrumental variable based on Asian reserve accumulation described above). Both stronger foreign demand for safe assets, and its mirror image – the financial-sector supply – are associated with lower real GDP growth in the medium term. The effects are large and persistent: an instrumented 1% of GDP increase in foreign demand, or in financial-sector supply, is followed by cumulatively 0.5–1 percentage point lower real GDP growth over the subsequent 5–8 years. Interestingly, we do not observe similar negative effects when safe assets are supplied by the public sector (though we do not have an instrumental variable for public-sector supply).

Figure 3. Sectoral safe assets and medium-term GDP growth, instrumented local projections

Our findings underscore the need to reconsider how economies manage the creation and allocation of safe assets in an increasingly complex global environment. Foreign demand for safety—including from emerging markets—has become a major force shaping the financial systems of advanced economies. Much of this demand continues to be met by financial institutions, whose method of producing safe assets—issuing liabilities backed by risky loans—can fuel domestic credit booms and ultimately contribute to financial instability.

Looking ahead, the path is far from straightforward. If emerging markets continue to rely on advanced economies to supply safe assets, the latter will need to carefully manage how this demand is accommodated—balancing growth, credit risk, and financial stability. Yet in a world of rising geopolitical tensions and potential financial fragmentation, emerging markets may increasingly seek to generate their own safe assets, a process that comes with its own set of trade-offs and risks (Clayton et al., 2024, 2025; Cuevas, 2024; Gallo et al., 2024).

The future of the safe-asset landscape will depend not only on global demand, but also on who is trusted to supply safety. As our research shows, getting this balance right is essential for a more resilient global financial system.

Ahnert, T., and Perotti, E. (2021). Cheap but flighty: A theory of safety-seeking capital flows. Journal of Banking & Finance 131: 106211.

Bernanke, B. S. (2005). The global saving glut and the US current account deficit. Speech No. 77, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Caballero, R. J., Farhi, E., and Gourinchas, P.-O (2017). The safe assets shortage conundrum. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(3): 29–46.

Caballero, R. J., and Simsek, A. (2020). A model of fickle capital flows and retrenchment. Journal of Political Economy 128(6): 2288–2328.

Castells-Jauregui, M., Kuvshinov, D., Richter, B., & Vanasco, M. (2025). Foreign demand for safety and macroeconomic instability. CEPR Discussion Paper 19025.

Clayton, C., Dos Santos, A., Maggiori, M., & Schreger, J. (2024). International currency competition. Available at SSRN 5067555.

Clayton, C., Dos Santos, A., Maggiori, M., & Schreger, J. (2025). Internationalizing like China. American Economic Review, 115(3), 864-902.

Cuevas, C. (2023). Safe assets in emerging market economies. Working paper.

Gallo, A., Gao, D., and Ioannidou, V. (2024). China’s savings glut and investors hunt for safe assets. Available at SSRN 5072411.

Gourinchas, P.-O., & Jeanne, O. (2012). Global safe assets. BIS Working Paper 399.

Maggiori, M. (2017). Financial intermediation, international risk sharing, and reserve currencies. American Economic Review, 107(10), 3038–3071.

Nakamura, E., & Steinsson, J. (2011). Does fiscal stimulus work in a monetary union? Evidence from US regions. VoxEU Column. Available at https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/does-fiscal-stimulus-work-monetary-union-evidence-us-regions.