This policy brief is based on BIS Working Papers No 1304. The views expressed in this brief do not necessarily reflect those of the Central Bank of Chile or its board members. All errors are my own.

Abstract

I build hand-collected data with biographical information on central bank leaders across more than 200 countries. I show that gender, age, education and career profiles changed substantially since the 1980s. Recent years show more women, PhDs, people with previous roles in finance ministries and older central bankers. I then show life experience influences monetary policy, even after accounting for other macroeconomics observables in the empirical Taylor rule. The role of personal experience for monetary policy is statistically significant across different country groups, although the effect is smaller in advanced economies.

Monetary policy makers take decisions under uncertainty. In real time it is not clear what is the true model of the economy, the nature of the macro shocks, or how agents learn and form decisions (Primiceri 2006). Economic policy makers take decisions based on a mix of available data, advice and analysis from staff and their own personal experience. Previous studies show that monetary policy in the US is influenced by the inflation rates observed during the lives of the FOMC members (Malmendier et al. 2021) and by their education and experience during the impressionable years (Bordo and Istrefi 2023). However, knowledge of policy makers expectations and motives is much more incipient than behavioral studies of consumers, experts, firms or even CEOs (Malmendier 2021).

My recent research provides an extensive study of the macroeconomic experience, education and careers of central bank leaders across the world (Madeira 2025). I built a hand-collected dataset for more than 3,000 central bank leaders (governors, deputy governors, board members) with biographical information on birth dates, gender, education and career background.

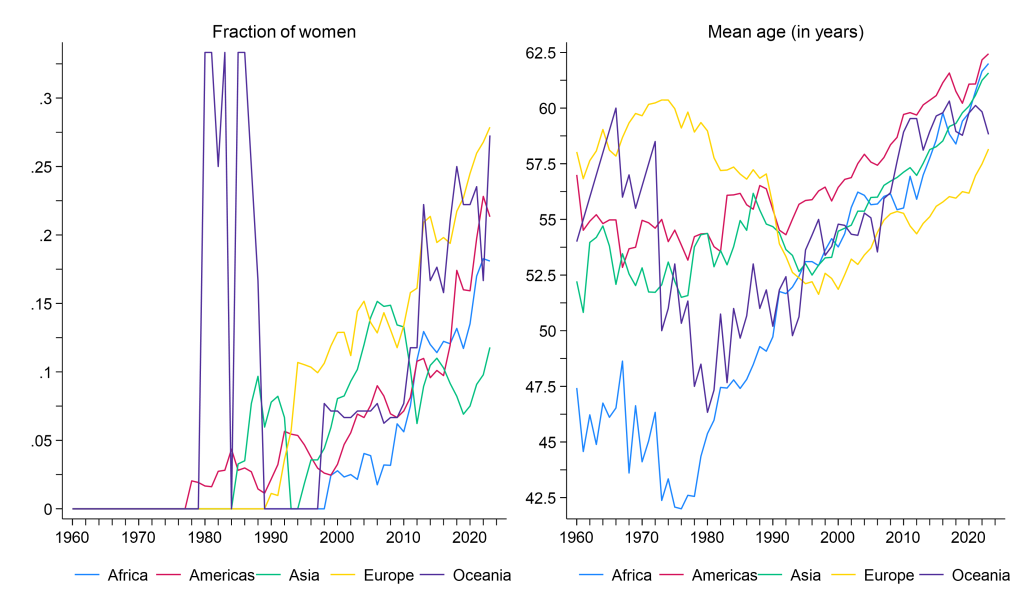

Central bankers changed substantially their demographic characteristics since the early 1960s, as shown in Figure 1. Women were entirely absent from central bank leadership until the mid-1970s. The fraction of women in the data increased steadily across all continents until the recent years, except for Asia where the presence of women declined over the last 15 years. Current females represent around 10% in Asia, 15% in Africa, 20% in the Americas, and 25% in Europe and Oceania. Age also changed over the years. Central bank leaders became younger during the 1970s and 1980s. Mean age has been steadily increasing across all continents since the 1990s.

Figure 1. Fraction of women and mean age of central bank leaders over time

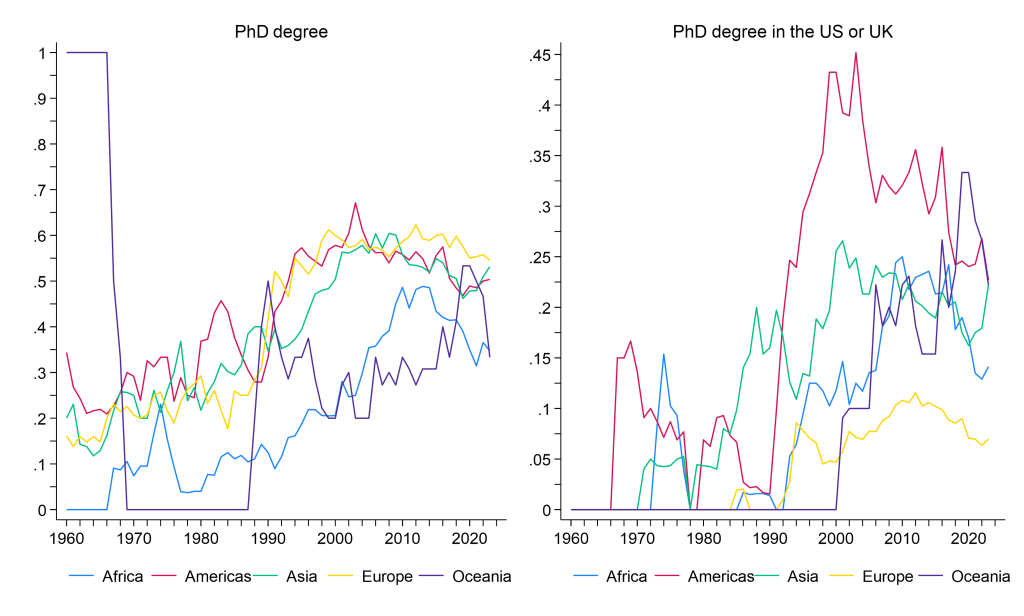

Education and studies abroad increased significantly across all continents. Figure 2 shows that the fraction of PhDs in central bank leadership increased from around 20% in the early 1970s to 40% or more in recent years. There is also an increasing share of central bankers with studies abroad in the US or UK (a measure that excludes nationals of those countries). In the early 1960s, few central bankers had studies abroad in the US or UK. But this fraction increased in the 1970s, especially in the Americas, Africa and Asia. The early 2000s saw a peak of US-UK PhDs in the Americas and Asia, which reached fractions of 45% and 25% respectively. In Oceania the share of US-UK PhDs kept increasing and peaked around 35% shortly before the pandemic. The share of US-UK PhDs in Europe is much lower, fluctuating around 10% since the early 2000s.

Figure 2. Fraction of PhDs and PhDs with studies abroad in the US or UK

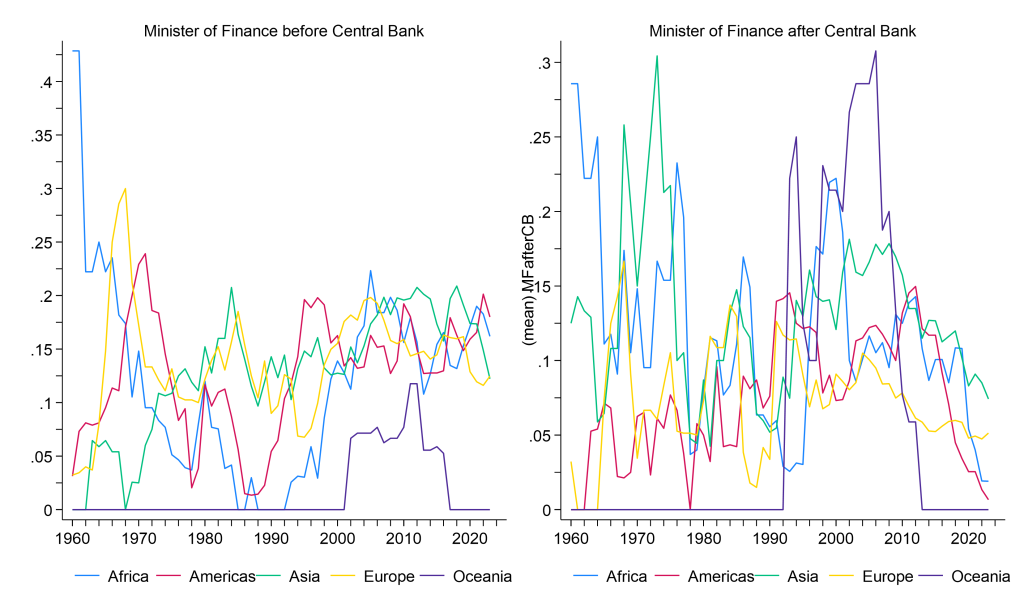

A surprising finding is that there is a significant revolving door between central banks and ministries of finance. Around 21% of the central bankers in the sample had some mandate in the treasury or ministry of finance. The share of central bankers that had previous roles at the ministry of finance has fluctuated between 10% and 20% for all continents since the early 1980s, except for Oceania. In Oceania very few central bankers had previous roles at the ministry of finance, but a significant fraction move to the ministry of finance after their central bank mandate ends. In other continents, the fraction of central bankers moving to roles at the ministry of finance after their central bank career has fluctuated between 5% and 15% since the early 1990s. Therefore, people that had careers both in fiscal and monetary institutions are not an exception.

Figure 3. Fraction of central bank leaders with ministry of finance roles before or after their central bank mandates

The major question of the work is whether life experience affects monetary policy. To test this, I estimate a cross-country Taylor rule, which accounts for life experience and the traditional inputs such as the previous monetary policy rate, past inflation and GDP growth, and fixed effects for country and time. Life experience is accounted for with experience-based forecasts (EBF) for the future inflation and GDP growth (Malmendier et al. 2021, Pedemonte et al. 2025). These EBF forecasts use all the inflation and GDP growth observed since the policy makers became adults at age 18. Each period the EBF forecast is updated recursively using new observations, which are incorporated according to a learning speed parameter (Malmendier et al. 2021).

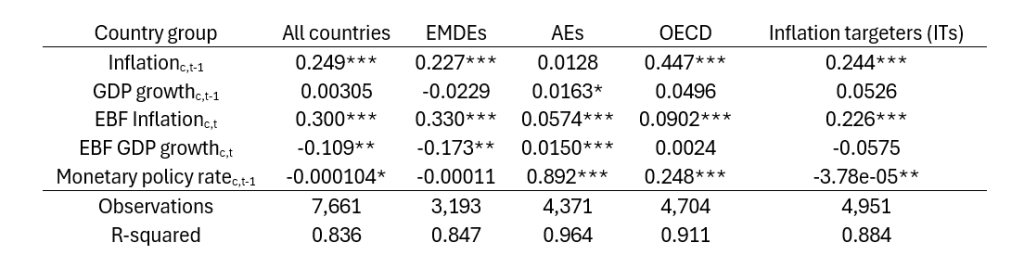

The effect of life experience and the other Taylor rule inputs on the monetary policy rate is then obtained across different country groups, including all countries, emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), advanced economies (AEs), current OECD members and inflation targeting economies (ITs).

The results show that life experience forecasts for inflation are a relevant input for the Taylor rule of any country group. Furthermore, EBF inflation forecasts are even more relevant than previous inflation in determining monetary policy for several economies, including the samples of all countries, EMDEs and AEs. In the sample of all countries, an increase of 1% in the chair’s experience-based inflation forecast implies a tightening of 30 basis points in the monetary policy rate. The role of experience in monetary policy decisions appears to be more relevant in the lower income economies (EMDEs).

Table 1. Quarterly panel regressions of the monetary policy rate based on the chairs’ life experience

(inflation and real GDP growth) forecasts (year on year)

All regression include country and time fixed effects (omitted).

∗∗∗, ∗∗, ∗ denote 1%, 5%, 10% statistical significance.

The results are robust to several specifications (Madeira 2025) including interactions with career connections of the central bankers with the ministry of finance or with measures of central bank autonomy (Romelli 2024).

I also find experience explains the tone in central bank speeches for climate concerns (Campiglio et al. 2025) and monetary policy, inflation and financial stability sentiments.

This study shows that life experience is a relevant input for the monetary policy rate decisions across several economies, even after other observable macroeconomic information is accounted for. Future research will study how central bank efficiency and the inflation sacrifice ratios (Forbes et al. 2025) change with governors’ life experience. It is also relevant to study how much of the dissent votes and disagreement in policy views can be determined by life experience (Malmendier et al. 2021, Madeira et al. 2023). This is especially relevant in emerging markets where a long memory of past inflation can affect current expectations and monetary policy perceptions (Magud and Pienknagura 2025, Jacome et al. 2025).

Bordo, M. and K. Istrefi (2023), “Perceived FOMC: The making of hawks, doves and swingers,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 136, 125-143.

Campiglio, E., J. Deyris, D. Romelli and G. Scalisi (2025), “Warning words in a warming world: Central bank communication and climate change,” European Economic Review, 178, 105101.

Forbes, K., J. Ha and M. Kose (2025), “Tradeoffs over Rate Cycles: Activity, Inflation, and the Price Level,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, volume 40.

Jacome, L., Magud, N, S. Pienknagura and M. Uribe (2025), “The Legacy of High Inflation on Monetary Policy Rules,” SUERF Policy Brief 1321.

Madeira, C., J. Madeira and P. Monteiro (2023), “The origins of monetary policy disagreement: the role of supply and demand shocks”, Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Madeira, C. (2025), “The life experience of central bankers and monetary policy decisions: a cross-country dataset,” BIS Working Papers 1304, Bank for International Settlements.

Magud, N. and S. Pienknagura (2025), “Inflated concerns: Exposure to past inflationary episodes and preferences for price stability,” Journal of International Economics, 158, 104181.Malmendier, U. (2021), “Experience Effects in Finance: Foundations, Applications, and Future Directions,” Review of Finance, 25(5), 1339-1363.

Malmendier, U. (2021), “Experience Effects in Finance: Foundations, Applications, and Future Directions,” Review of Finance, 25(5), 1339-1363.

Malmendier, U., S. Nagel and Z. Yan (2021), “The making of hawks and doves,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 117, 1942.

Pedemonte, M., H. Toma and E. Verdugo (2025), “Aggregate Implications of Heterogeneous Inflation Expectations: The Role of Individual Experience,” IDB WP 1699, https://doi.org/10.18235/0013495.

Primiceri, G. (2006), “Why Inflation Rose and Fell: Policy-Makers’ Beliefs and U. S. Postwar Stabilization Policy,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(3), 867–901.

Romelli, D. (2024), “Trends in central bank independence: a de-jure perspective,” BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 217.