This Policy Brief is based on Bank of Italy, Occasional Papers Series, No. 807/23. The views expressed are those of the authors an do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy or the Single Resolution Board.

We focus our analysis on the implementation of the too-big-to-fail (TBTF) regulatory framework, finalized after the global financial crisis of 2007-08, on the large banks of the EU Banking Union (BU). In spite of the extensive integration between the BU’s prudential and resolution frameworks, we find that some further improvements could be achieved: 1) the assessments of a bank’s systemic importance and its resolvability could be made more consistent; 2) recovery and resolution plans could be better coordinated; 3) the interaction between capital buffers and minimum requirements could deserve deeper consideration; 4) the information sharing between the micro-prudential and resolution authorities on one hand, and the macro-prudential ones on the other hand, could be reinforced. In this context, we also make reference to the work under way at the international level to draw lessons from the episodes of banking crises which occurred in 2023.

The too-big-to-fail (TBTF) reforms finalized after the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-08 involve the interplay between the micro/macro prudential and the resolution frameworks, designed to be closely interconnected, since their common objective is to shield the financial system and the real economy from the consequences of the failure of a large and systemic bank.

In the EU Banking Union (BU) the implementation of the TBTF reforms falls under the remit of different types of authorities (micro-prudential, macro-prudential, resolution authorities) at the national and supra-national levels. Such an institutional architecture could in principle make the adoption of an integrated approach among the going and gone-concern regulatory frameworks more challenging. To ensure an effective implementation, cooperation mechanisms and specific arrangements have been established to foster information-sharing among different authorities on a regular basis and in specific areas, with additional provisions to strengthen and speed-up the coordination in crisis prevention and management.

We explore how the TBTF framework has worked in practice in the EU BU, examining how the large banks’ prudential and resolution frameworks have worked as part of an integrated approach in the following areas: a) consistency between systemic importance and resolvability assessment; b) recovery and resolution planning and the exchange of information in crisis preparedness and management; c) interaction between capital buffers and going/gone concern requirements. In doing so, we refer to the EU ‘significant’ banks, that is, those banks supervised directly by the ECB and as a consequence under the direct remit of the SRB.1

The recent episodes of financial distress of March-May 2023 occurred in the US2 and Switzerland3 have revived the attention on the adequacy of the framework defined in the post-GFC years and on its correct implementation. Moreover, there has been a renewed focus on the negative financial stability implications arising when the domestic implementation of the post-GFC internationally agreed rules follows divergent patterns across jurisdictions in a number of key prudential requirements.4

Both the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) have undertaken a review of the 2023 banking turmoil and actions undertaken by the authorities, with a view to draw lessons in the prudential and resolution fields.5 There is a general consensus that these crisis episodes have stressed the importance of a full and consistent implementation of the internationally-agreed prudential standards for internationally-active banks, and the need to develop a balanced regulatory and supervisory approach for banks which are not internationally active, but which may determine a systemic risk in individual jurisdictions.

The wave of reforms finalized after the GFC represents a shift towards a multi-layered system with a higher number of constraints at play. Since a regulatory framework mainly based upon a single measure (i.e., risk-based capital adequacy requirements for banks) may not succeed in dealing with the externalities/frictions stemming from the financial system, the post-GFC reforms foresee special rules for large financial institutions, whose failure poses a threat to the global financial system.6

The reforms have been implemented through micro-prudential supervision and resolution policies, and through macro-prudential measures. The three frameworks aim at reducing the expected loss to the financial system and to the real economy from the failure of a large bank by reducing both the probability of default (PD) and the loss given default (LGD). The loss arises in the event of failure of an institution due to idiosyncratic reasons or to direct and indirect contagion. An increased loss absorbency capacity through the introduction of capital buffers as well as a more intense supervision are effective on the reduction of the probability that a bank defaults, while credible recovery and resolution plans are instead more targeted to reduce the loss once the bank defaults.7

The progress of the post-GFC TBTF reforms across G20 jurisdictions has been assessed annually by the FSB, with the objective to promote their consistent implementation, prevent regulatory arbitrage, and ensure cross-border coordination. According to the latest evidence, the implementation of the policy framework for global systemically important financial institutions has advanced the most in the case of banks.8 In 2021, the FSB has published a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of the post-GFC reforms for systemically important banks. Notwithstanding the positive elements underlined, the report also points out that a number of gaps need to be addressed if the overall benefits of the TBTF reforms are to be fully reaped.9

Turning to the implementation of the TBTF framework in the EU BU, the classification of banks according to their significance or systemic importance and the resolvability assessment are carried out separately, on the basis of different sets of criteria and by different authorities (supervisory, macro-prudential, and resolution authorities), at national and supra-national level. Nevertheless, there seems to be a reasonable degree of consistency in the application and evolution of these frameworks.

In the first place, the enhancement of the Public Interest Assessment by the SRB in 2021 to take into account system-wide events allows to evaluate whether a bank’s failure triggers a financial stability issue, indicating that resolution is in the public interest, or, in case of a bank already earmarked for resolution, affecting the choice of the most adequate resolution tool in the given circumstances.10

Secondly, the 2022 EBA Guidelines on the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process envisage that the supervisory authorities include the MREL requirement in the list of key indicators subject to regular monitoring and assess the impact of institutions’ stress tests also on their eligible liabilities; more in general, in assessing the viability of institutions’ business models and strategic plans, the supervisors should also consider recovery and resolution plans, including the results of the resolvability assessment provided by resolution authorities.

Thirdly, the 2014 EBA Guidelines on the systemic importance of domestic banks have outlined the importance of resolvability, which can be a significant input to be used optionally to complement the prudential dimension. There is not specific evidence, so far, that this option has actually been used in any jurisdiction. This may be related to the fact that no specific indicator is mentioned in the EBA GL. Furthermore, this may also depend on the fact that the achievement of resolvability is still on-going. In the near future, it may therefore make sense to incorporate it both in the classification of banks according to their systemic relevance and in order to define consistent actions that could be taken at macro-prudential level.

Fourthly, recent changes in the methodology for the identification of systemic banks at global and European level point to the introduction of a more systematic interaction between systemic relevance and resolvability assessments. In 2022, the BCBS has carried out a targeted review of the treatment of cross-border exposures within the BU for the purposes of the identification of globally systemic banks (G-SIB). The BCBS has acknowledged the progress made in the development of the BU, including the resolution framework, and agreed to recognise this progress in its G-SIB framework, allowing for adjustments to be made according to supervisory judgment. In practice, a reduction of the score assigned to each G-SIB is allowed for BU banks, resulting from treating cross-border exposures within the Banking Union as domestic exposures.

Finally, in the context of the review of the crisis management and deposit insurance framework (CMDI) in the EU, the recent proposal of the EU Commission incorporates the performance of critical functions at regional level, not any longer at national level only, thus paving the way for a greater consistency between the assessment of resolvability for the banks earmarked for resolution and the classification of banks at local level in relation to the impact of their failure on the real economy.

The integration and convergence of the prudential and resolution frameworks relies also on the efficiency of the information exchange between different authorities. Cooperation between prudential supervisors and resolution authorities is essential to ensure a smooth resolution process of institutions. The FSB Key attributes for effective resolution regimes recommend jurisdictions to ensure that an appropriate exchange of information between supervisory and resolution authorities is in place, both in normal times and during a crisis, at a domestic and a cross-border level.

In this context, the revision of the MoU between ECB and SRB in December 2022 aimed at enhancing cooperation and fostering convergence between the two authorities. As concerns the cooperation in crisis times, in Early Intervention (EI) the MoU reinforces the principle by which the ECB shares with the SRB its assessment on EI conditions and the potential measures to be taken at the same time they are submitted to the supervisory decision-making body, to enable the SRB to swiftly prepare for resolution; finally, on the failing-or-likely-to-fail condition (FOLTF), the ECB liaises with the SRB sufficiently in advance in the process.

With reference to the criteria for information exchange, the information is shared between the ECB and SRB: (i) automatically (without request); or (ii) upon simple written request; or (iii) upon formal request. The MoU has enhanced automatic information sharing both in normal and crisis times. The revision reflects also the ECB-SRB cooperation on liquidity, which involves the development of a joint liquidity template and the automatic exchange of data based on this template.

In addition to supervisory information, there is other information, collected by central banks, which is crucial for the resolution authorities, like the Securities Holding Statistics (SHS) and AnaCredit databases.11 The analysis underpinning the PIA is dependent on having a regular and timely as well as highly granular access to relevant data. The resolution authorities have not generally access to this information, that is why the SRB has finalised in August 2023 a Memorandum of Understanding with the ECB on this aspect12, which will allow the PIA assessment, the valuation of the bank’s balance sheet and the analysis of risks to be based on much more in-depth, granular information.

Finally, closer cooperation between resolution authorities and macro-prudential authorities may also be beneficial. The exchange of information may help to deal with different aspects, such as the distribution restrictions when buffers are breached in the MREL framework or the overlap of capital buffers with minimum requirements. In this regard, it is worth noting that the April 2023 Commission proposal on the revision of the Crisis management framework (Crisis Management and Deposit Insurance, CMDI) envisages a modification of art. 30 and 34 SRMR to enhance the exchange of needed information among authorities.

Capital buffers play a key role within the post-GFC regulatory reform, to the extent that they allow banks to tackle risks more effectively in going-concern situations. If buffers overlap with minimum prudential or resolution requirements, their effectiveness in increasing the overall loss absorbency in the banking system might be to some extent overestimated. The reason behind the less than-complete usability of capital buffers is that most regulatory frameworks envisage such buffers as an additional cushion with respect to risk-weighted minimum requirements (Pillar 1 and Pillar 2), but not with respect to other requirements. Therefore, the capital instruments used to accumulate risk-weighted buffers can at the same time fulfil the minimum leverage ratio or the TLAC/MREL requirement. This prevents banks from exploiting, in case of need, these accumulated buffers without breaching other requirements.

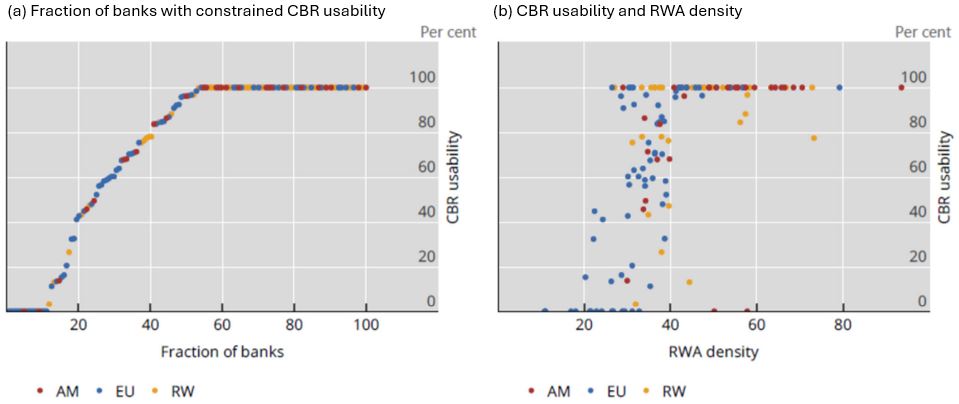

In mid-2021, BCBS (2022) highlights that about 10 per cent of international banks had no room at all to use their combined buffer requirement (CBR), and close to half sample had a partial capability to dip into their accumulated buffers, due to parallel requirements. The distribution of these banks was uneven across jurisdictions and across business models. In particular, almost all the cases of imperfect usability were found at banks with low RWA density (below 40 per cent), i.e. typically banks with more sophisticated IRB models, often the largest ones. This lends support to the conclusion that usability issues are also TBTF issues.

Figure 1: CBR usability across 144 banks in H1 2021 (leverage ratio interaction)

Note: The sample includes 144 banks from the following regions: AM = America, EU = Europe, RW = Rest of the world. CBR usability of European banks might be slightly underestimated as AT1 and T2 shortfalls of pillar 2 minimum requirements are not taken into account. Source: BCBS.

In the EU, potential avenues to increase buffer usability could be framed within a wide-ranging review of the EU macro-prudential framework, which acknowledged the materiality of the issue of the interaction between micro-prudential, macro-prudential and resolution frameworks along with the lack of coordination between authorities, which can result in conflicting policy measures or double counting.

A possible remedy to an insufficient amount of usable buffers could be that macro-prudential authorities impose higher levels of releasable buffers. In this option, the tightening of the framework would be asymmetric, since its impact on banks would depend on the quality of instruments that banks use to comply with capital regulations. The adjustment costs to comply with higher capital buffers would also differ across jurisdictions that currently implement heterogeneous buffer levels, with a larger catching-up effort imposed on banks from low-buffer jurisdictions and a subsequent modification of the level playing field.

Alternatively, the regulatory framework could be changed, with a view to making it more symmetric across prudential and resolution purposes, and across risk-weighted and unweighted (leverage/MREL) requirements. Concretely, leverage buffers could be imposed that mirror all risk-weighted buffers, for both prudential and resolution purposes. However, such a measure would be very conservative, it would be equivalent to a generalized increase in the buffer requirements, which would imply significant additional costs for institutions, and would increase the complexity of the overall framework.13

The revision of the regulatory framework would require a very close coordination among authorities. The EU micro-prudential or resolution authorities currently are not obliged to inform macro-prudential authorities about their supervisory measures or about detected breaches. The involvement of macro-prudential authorities through timely information flows, both on capital breaches and the envisaged recovery plans, is particularly crucial when the largest banks are concerned, since the potential macro-prudential impact of their capital weakness is larger. An additional solution to tackle the issue – at least partly – would entail changing the composition of the capital instruments through which the recapitalization amount of the MREL requirement must be fulfilled. At the moment there is no explicit requirement in the EU regulation for banks to use MREL eligible liabilities or capital instruments other than CET1 for such purposes.

Such a prescription, that we specifically refer to the recapitalization amount of the MREL requirement (in order not to touch supervisory ratios) would help reduce the buffer overlap, on one side, and make a FOLTF bank recapitalization easier, on the other: in fact, CET1 absorbs losses automatically, thus entailing the risk that when a bank approaches the FOLTF the capital has already disappeared and the recapitalization amount is not available exactly at the moment it is more needed, specifically in the case of banks meeting the recapitalization amount only with CET1 instruments. This option assumes the capacity for banks to tap the institutional market for meeting the MREL recapitalisation requirement with instruments other than CET1.

Our analysis suggests that in the EU BU it is important to enhance coordination and information sharing across all authorities involved in micro- and macro-prudential regulation and in crisis management, in order to adopt a comprehensive approach that avoids creating a rigid differentiation between the going and gone concern policies. To achieve this objective, the different authorities should share the information considered to be necessary for their respective mandate/tasks. Moreover, interactions between going and gone concern requirements should be taken into account to avoid any impact on their effectiveness and loss-absorbency capacity. The current juncture might be the right time to consider how to effectively improve the interplay between going and gone concern regulatory frameworks, with the objective to further address the TBTF problem in the EU BU.

BCBS, (2023), “Basel Committee to review recent market developments, advances work on climate-related financial risks, and reviews Basel Core Principles”, March.

Board of the Governors of the Federal Reserve System, (2023), “Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank”, 28 April.

ESRB, (2021), “Report of the Analytical Task Force on the overlap between capital buffers and minimum requirements”, December.

FSB, (2021), “Evaluation of the Effects of Too-Big-To-Fail Reforms – Final Report”, April.

FSB, (2023a), “FSB to consider lessons learned from recent banking-sector turmoil”, 12 April.

FSB (2023b), “2023 Bank Failures. Preliminary lessons learnt for resolution”, October.

FSB (2023c), “Promoting global financial stability”, October.

Laviola S., (2021), “System-wide events in the Public Interest Approach”, SRB Blog Post, May.

Swiss Federal Department of Finance, (2023), “The need for reform after the demise of the Credit Suisse”, Report of the Expert Group on Banking Stability, September.

SRB, (2023), ‘ECB and SRB sign Memorandum of Understanding to share confidential data’, 4 August.

Trapanese M., (2020), “Regulatory cycle in banking: What lessons from the US experience?”, Bank of Italy, Occasional Papers Series, No. 585, November.

Trapanese M., (2022), “Regulatory complexity, uncertainty, and systemic risk”, Bank of Italy, Occasional Papers Series, No. 698, June.

Trapanese M., (Coordinator), Bellacci S., Bofondi M., De Martino G., Laviola S., and Vacca V., “The interplay between large banks’ prudential and resolution frameworks: do we need further improvements?”, Bank of Italy, Occasional Papers Series, No. 807, October.

Turner Ph., (2023), “What are the systemic lessons of SVB?”, Central Banking Online, March 20.

Visco I., (2013), “The Financial Sector after the Crisis”, Speech by the Governor of the Bank of Italy, BIS Central Bankers, March.

Woods S., (2022), ‘Bufferati’, Speech of the Bank of England Deputy Governor at City Week 2022, 26 April.

A more in-depth analysis of these policy issues can be found in Trapanese et al. (2023).

For a review of the US crisis episodes, see: Board of the Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2023).

For more details on the Swiss case, see Swiss Federal Department of Finance (2023).

See: Turner (2023); and Trapanese (2020).

See: BCBS (2023); FSB (2023a); and FSB (2023b).

For an extensive analysis of the post-GFC regulatory repair see: Visco (2013); and Trapanese (2022).

The FSB post-GFC policy framework has been defined through a building-block approach consisting of a high number of reports/documents/recommendations since 2010.

See FSB (2023c).

In particular, the FSB (2021) report concludes that: there are several key areas where improvements to the resolvability of systemic banks could still be made; there is a need to improve provision and availability of data and to consider the adequacy of current level of transparency for market participants; there is scope for SIBs to improve their risk data aggregation and reporting frameworks, in order to assess all risks in an appropriate manner; the residual gaps in the information available to public authorities, to the FSB, and to other standard setters reduce their ability to monitor and evaluate; further monitoring is needed regarding the application of the reforms to systemic banks at domestic level.

See Laviola (2021).

For general information on SHS and AnaCredit see: https://data.ecb.europa.eu/methodology/securities-holdings-statistics and https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/money_credit_banking/anacredit/html/index.en.html.

See SRB (2023).

See: ESRB (2021); and Woods (2022).