This policy brief is based on Falck and Schulte (2025), Deutsche Bundesbank, Discussion Paper, No 27/2025. The views expressed in this Policy Brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

This Policy Brief presents new evidence on how global seasonal temperature shocks influence world food commodity markets. Using monthly data from 1961 to 2023, we show that global temperature shocks – measured as deviations from seasonal norms of the past five years – lead to substantial and persistent increases in global food commodity prices. A global summer shock of 0.4°C raises world food prices by roughly 10% within a year and reduces global food commodity production by about 3%. Other seasons show negligible impacts. The evidence points to a clear mechanism: summer heat acts as a negative supply shock to global agricultural markets. These findings imply that climate variability is a significant macroeconomic driver, reinforcing the need to incorporate seasonal climate risks into inflation forecasting, food security planning, and macro-financial surveillance.

Global food commodity prices are highly volatile and have significant macroeconomic importance. Being able to forecast them and to understand the drivers behind this volatility is crucial, as changes in food prices can markedly impact economic activity and inflation dynamics (De Winne and Peersman, 2021; Peersman, 2022).

While a large literature has documented how local weather shocks depress local agricultural yields, much less is known about how global weather conditions shape global food markets. This gap is important for two reasons: (1) many food commodity markets are globally integrated, (2) recent research suggests that global temperature variation might be more closely related to extreme weather events than local temperature shocks (Bilal and Känzig, 2024).

Understanding how seasonal global temperatures affect global food commodity prices is therefore essential for forecasting inflation, designing agricultural policies, and assessing climate-related macro-financial risks.

To capture unexpected global weather fluctuations rather than long-term climate trends, we construct global temperature shocks as the deviation of a season’s global mean surface temperature from its rolling five-year average. This approach captures heat shocks that producers and markets could not anticipate based on experiences from past years. The analysis distinguishes between four seasons (defined from the perspective of the Northern Hemisphere) since the global food system is not equally sensitive to weather across the year.

Our core result is both intuitive and striking: Unexpected summer heat shocks have a strong, broad-based and persistent effect on global food prices. Those from other seasons have no or only mild effects.

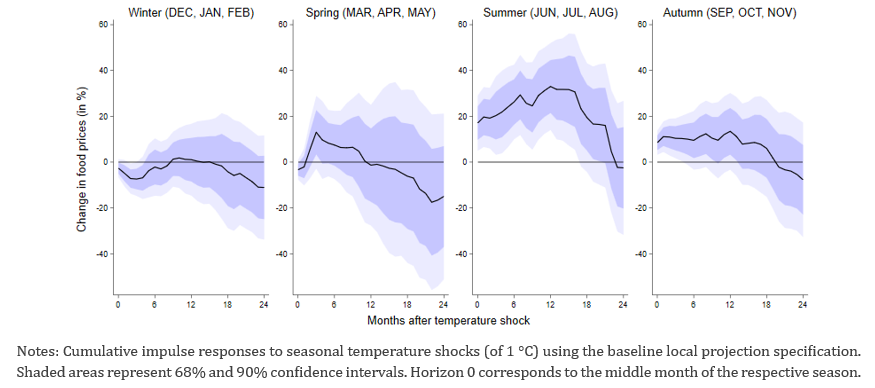

Using local projection methods (Jordà, 2005), we estimate the cumulative effect of a temperature shock on global food prices over a two-year horizon. Following a summer temperature shock of 0.4°C – similar to the ones in 2023 and 2024 – global food commodity prices increase by around 10% over the subsequent year. The rise begins quickly, within months of the shock, and remains elevated for more than a year, reflecting the time needed for markets to adjust to reduced crop availability. By contrast: Spring, autumn, and winter temperature shocks produce no economically meaningful or statistically significant impacts. This seasonality underscores that the global food system is mainly vulnerable to heat during the growing season of most crops.

Figure 1. Food commodity price impact of seasonal temperature shocks

The average price response masks large heterogeneity: Grains react the strongest. Vegetable oils and meals also rise sharply, while other foods appear to be less affected. These patterns reflect differences in growing cycles, geographical concentration, and heat sensitivity of crops.

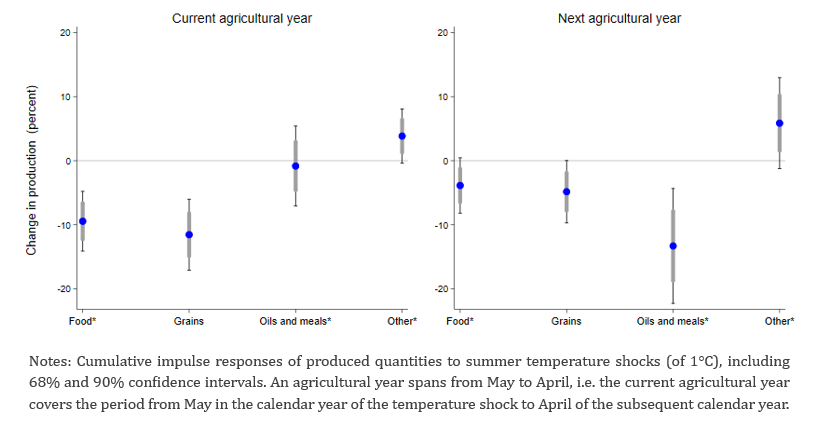

To understand the mechanism, we examine in addition global production data from 1960 to 2023. Production is measured at the agricultural-year level (May to April), which begins just before the start of the summer season. We find global food production to fall by around 2.9% after a 0.4°C summer temperature shock. Grain production declines even more, by about 3.6%. Effects dissipate after one agricultural year – consistent with a temporary supply disruption.

These mirrored movements in prices and quantities strongly indicate that summer heat functions as a global negative supply shock.

Figure 2. Food production impact of summer temperature shocks

Our analysis provides clear evidence that the global food system is highly sensitive to unexpected summer heat shocks. These shocks reduce global food production – especially grains – and raise global food prices for more than a year. As the climate might become more volatile, seasonal temperature anomalies might increasingly shape both inflation dynamics and food security outcomes. Policymakers, central banks, and international institutions should therefore integrate climate variability into their analytical toolkits – not only as a long-term risk, but as an immediate macroeconomic driver.

Bilal, A. and D. R. Känzig. 2024. “The Macroeconomic Impact of Climate Change: Global vs. Local Temperature.” NBER Working Paper, No. 32450.

De Winne, J. and G. Peersman. 2021. “The Adverse Consequences of Global Harvest and

Weather Disruptions on Economic Activity.” Nature Climate Change, 11: 665–672.

Falck, E. and P. Schulte. 2025. “From weather to wallet: Evidence on seasonal temperature shocks and global food prices.” Bundesbank Discussion Paper, No. 27/2025.

Jordà, Ò. 2005. “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections.”

American Economic Review, 95(1): 161–182.

Peersman, G. 2022. “International Food Commodity Prices and Missing (Dis)Inflation in

the Euro Area.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 104(1): 85–100.