References

Arslan, Yavuz, Mathias Drehmann, and Boris Hofmann, “Central bank bond purchases in emerging market economies,” 2020. BIS Bulletin No. 20.

Calvo, Guillermo A. and Carmen M. Reinhart, “Fear of Floating,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2002, 117(2), 379–408.

Cordella, Tito, Pablo M. Federico, Carlos A. Vegh, and Guillermo Vuletin, Reserve Requirements in the Brave New Macroprudential World number 17584. In ‘World Bank Publications – Books.’, The World Bank Group, 2014.

Fratto, Chiara, Brendan Harnoys Vannier, Borislava Mircheva, David de Padua, and He le ne Poirson, “Unconventional Monetary Policies in Emerging Markets and Frontier Countries,” 2021. IMF Working Paper, 21/14.

Hartley, Jonathan S. and Alessandro Rebucci, “An Event Study of COVID-19 Central Bank Quantitative Easing in Advanced and Emerging Economies,” 2020. CEPR Discussion Paper Series, DP14841, June.

IMF, “Bridge to Recovery,” Global Financial Stability Report, 2020. October.

Kaminsky, Graciela L., Carmen M. Reinhart, and Carlos A. Ve gh, “When It Rains, It Pours: Procyclical Capital Flows and Macroeconomic Policies,” in “NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2004, Volume 19” NBER Chapters, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, November 2005, pp. 11–82.

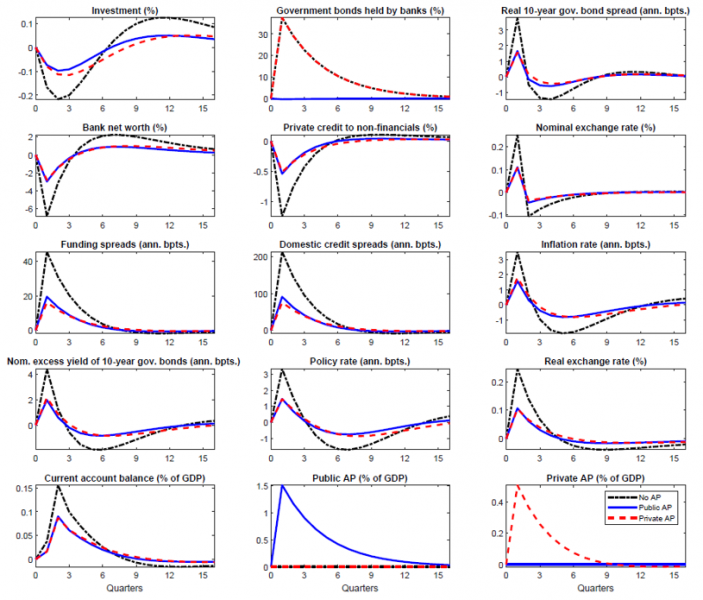

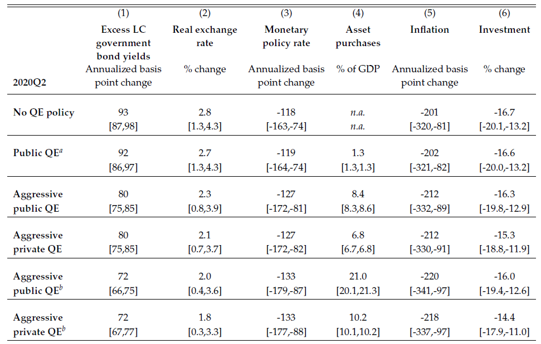

Mimir, Yasin and Enes Sunel (2023): “Fear (no more) of Floating: Asset Purchases and Exchange Rate Dynamics”, ESM Working Papers, No 57.

WB, “Global Economic Prospects,” 2021. January, World Bank.