This policy brief is based on Working Paper Series no. 1009. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

This paper studies how non-rational, extrapolative expectations interact with leveraged risk-taking to generate instability in financial markets and in aggregate economic activity. Drawing on Minsky and Kindleberger, we propose a macro-finance model in which investors tend to extrapolate recent events too strongly into the future when forming expectations and must periodically post collateral when borrowing to signal creditworthiness. We show that the combination of extrapolative expectations, pro-cyclical risk-taking by leveraged investors, and forced fire sales of productive assets during episodes of financial distress amplifies economic fluctuations, generating larger economic booms and deeper busts relative to an environment where agents form rational expectations. From a policy perspective, these dynamics justify tighter financial regulation than under rational expectations, regardless of whether regulators themselves share private agents’ optimism or pessimism. The analysis highlights how well-designed macroprudential interventions can mitigate instability and improve long-run welfare.

The Financial Instability Hypothesis (FIH), articulated by Hyman Minsky and Charles Kindleberger, describes recurring cycles of optimism, leveraged expansion, and abrupt collapses in economic activity and investor sentiment. During upswings, investors become excessively optimistic relative to what historical data would justify, sharply increase borrowing, and undertake highly risky, heavily leveraged investments. When expectations eventually fail to materialize, investors suffer large losses and must fire-sale highly productive assets at severely dislocated prices to quickly deleverage – to thus meet pressing collateral requirements. The experienced financial turmoil then drives investors toward excessive pessimism, which leaves sound investment opportunities unexploited and delays recovery. Once distress subsides and confidence returns, a new wave of optimism takes hold, sowing the seeds of the next financial crisis.

We formalize these narratives in a compact yet tractable model and ask two central questions:

We consider an economy with two production technologies: a safer, lower-productivity technology, and a riskier, higher-return technology. Expert financiers (banks and other leveraged intermediaries) can leverage and operate the risky technology, but face tight collateral requirements; by contrast, non-expert households can only invest in the safer technology and face no financing constraints. Two frictions drive financial and economic instability:

Together these frictions interact through a real risk-taking channel: changes in sentiment and in financiers’ net worth mechanically alter the allocation of the economy’s productive asset between safe and risky technologies. Specifically, in expansions, rising optimism and wealth encourage greater risk-taking; in contractions, pessimism and weakened balance sheets sharply reduce risk-taking. Relative to a rational-expectations benchmark, diagnostic expectations:

Figure 1. Cyclical implications of financial frictions and diagnostics expectations

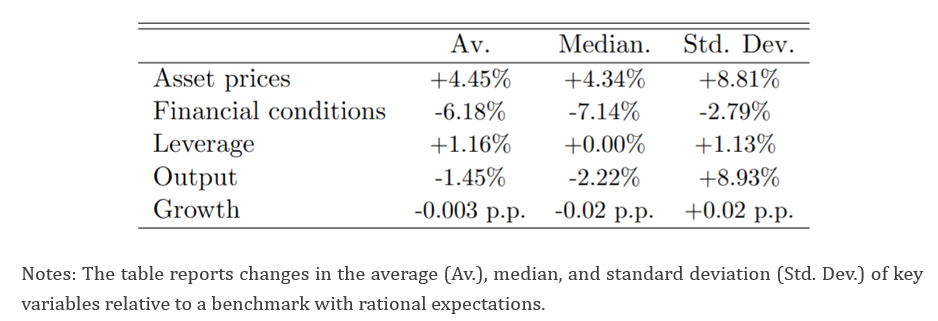

In short, financial and economic cycles become more unstable, more asymmetric, depress economic activity. In a standard calibration the additional instability induced by diagnostic expectations is quantitatively meaningful.

Table 1. Quantitative Implications of Diagnostic Expectations to Financial Instability

The model features a motive for policy intervention due to the presence of a pecuniary externality: private investment decisions influence asset prices and financial stability in ways not internalized by individual agents. This externality creates scope for macroprudential policy.

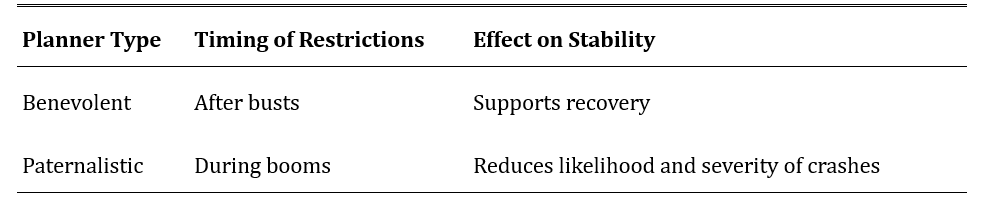

We study the policy interventions of two archetypal planners:

Both intervention types raise long-run welfare by mitigating financial amplification. However, paternalistic regulation typically achieves a higher average consumption level combined with lower consumption volatility.

Table 2. Policy Trade-Offs under Different Regulators

Our positive results align with historical accounts of financial and economic crises — notably the Global Financial Crisis, where extrapolative optimism in housing fed excessive leverage and was followed by fire-sale dynamics and a severe downturn. Empirical studies (e.g., Mian and Sufi 2011; Dell’Ariccia et al. 2012) document pro-cyclical risk-taking patterns consistent with the mechanism we propose.

Diagnostic (extrapolative) expectations and leveraged risk-taking jointly amplify financial instability, consistent with the Financial Instability Hypothesis. Importantly, optimal regulation must be tighter than under rational expectations, and the timing of macroprudential interventions depends on the expectation formation of the regulator. Our framework thus connects classical crisis narratives to modern macro-finance models, providing a positive account of cyclical dynamics and clear normative guidance for macroprudential policy.