This policy brief is based on OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1807. OECD Working Papers should not be reported as representing the official views of the OECD or of its member countries. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the authors.

Rapid population ageing generates economic and fiscal challenges in most OECD countries. Today’s ageing largely reflects past fertility, longevity, and migration developments. Hence, policies have limited capacity to counteract it and need to adapt to it. The extension of working lives as longevity rises could mitigate, but not completely offset, the negative effects of ageing on labour supply. However, most countries have room to raise employment in younger age groups. The impact of ageing on productivity growth is uncertain, as various micro and macroeconomic mechanisms act in different directions. Policies should support healthy ageing, employment, job quality and career transitions in all age groups, and promote older workers’ productivity by further developing lifelong learning and fostering an age-friendly management culture.

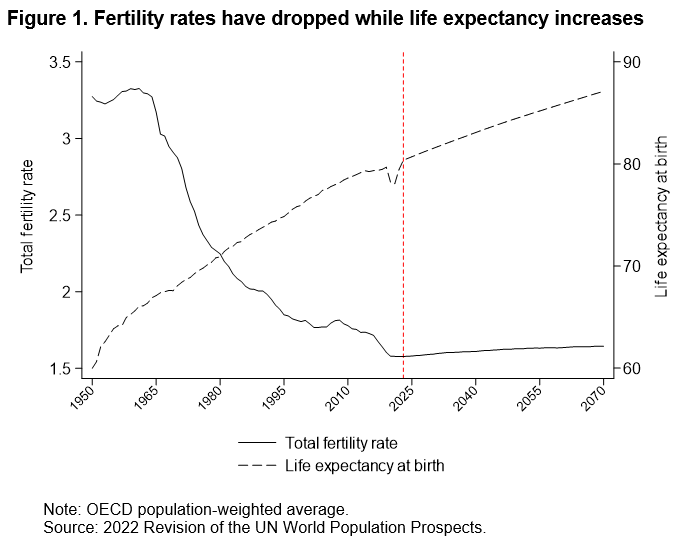

Population is ageing rapidly in most advanced economies, reflecting two demographic trends. First, life expectancy continues to increase steadily (Figure 1). This is a remarkable achievement, even more so as on average two-thirds of extra years of life are spent in good health. Second, the average fertility rate (the number of children per woman) has been roughly halved since the 1960s. Hence, retiring cohorts are replaced by much smaller inflows into the labour market, leading to a sharply rising old age dependency ratio (the number of people aged 65 and over relative to the working-age population, aged 20-64). In the absence of increases in labour participation and productivity gains, ageing mechanically lowers GDP per capita. In André, Gal and Schief (2024), we quantify the potential impact of ageing on labour supply and GDP per capita across OECD countries over the coming decades and explore policy options to address related challenges.

As ageing largely reflects past fertility, longevity and migration developments, policies can do little to change its course in the short to medium run. A rise in fertility rates would only raise the share of workers in the population in about two decades, when today’s newborn enter employment. Immigration can have a sizable impact on population growth and, with the help of well-designed integration policies, contributes to economic dynamism and innovation (Bernstein et al., 2022). However, even if immigration is important in some individual countries, stabilising the OECD-wide old-age dependency ratio would require much higher net immigration rates than those observed since the turn of the century.

Hence, OECD economies and societies will have to adapt to ageing. They can contain the slowdown or the fall in employment by promoting healthy ageing and encouraging longer working lives, and by better mobilising human resources in all age groups. Moreover, output per worker can be boosted through automation, investment in skills, and other productivity-enhancing policies, such as promoting competition and innovation, knowledge diffusion and investment in infrastructure (André and Gal, 2024).

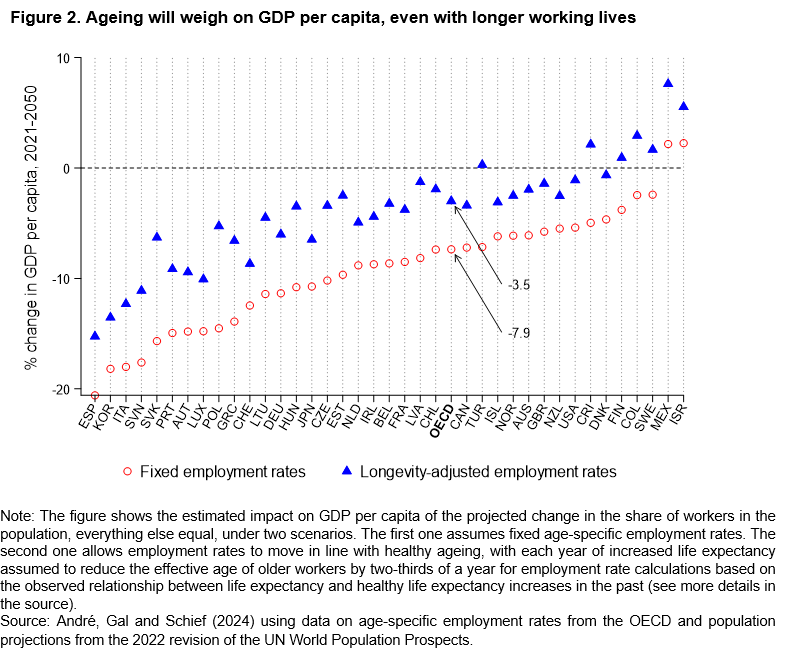

The fall in the share of workers in the population is projected to reduce, all else equal, per capita income across the OECD by nearly 8% over the next three decades, with some countries experiencing a shortfall of about 20% (Figure 2). However, employment rates have been rising in older age groups since the 1990s, reflecting not only amendments to pension systems and changes in labour market conditions and policies, but also a shift towards less physically demanding jobs and improved health among more recent cohorts of older workers (Geppert et al., 2019). Should these trends continue, they would mitigate the negative effect of ageing on the size of the workforce and GDP. Policies can support them in several ways.

Healthy ageing is a pre-condition for prolonging working lives, which should be supported through better integration of individuals in the economy and society, promoting healthier lifestyles at all ages, adapting health systems, and improving social and environmental health determinants. Fighting age discrimination and removing disincentives to continue working at older ages embedded in pension systems and other institutional arrangements is also crucial. Improving the quality of working environments can also allow and encourage workers to extend their working careers and lift their productivity. Lifelong learning needs to be stepped up to ensure that workers keep pace with rapid technological advances. Such policies could allow working lives to move in step with healthy life expectancy. If we assume that working lives lengthen in line with increases in healthy life expectancy, the ageing drag on GDP per capita is reduced by more than half on average (Figure 2).

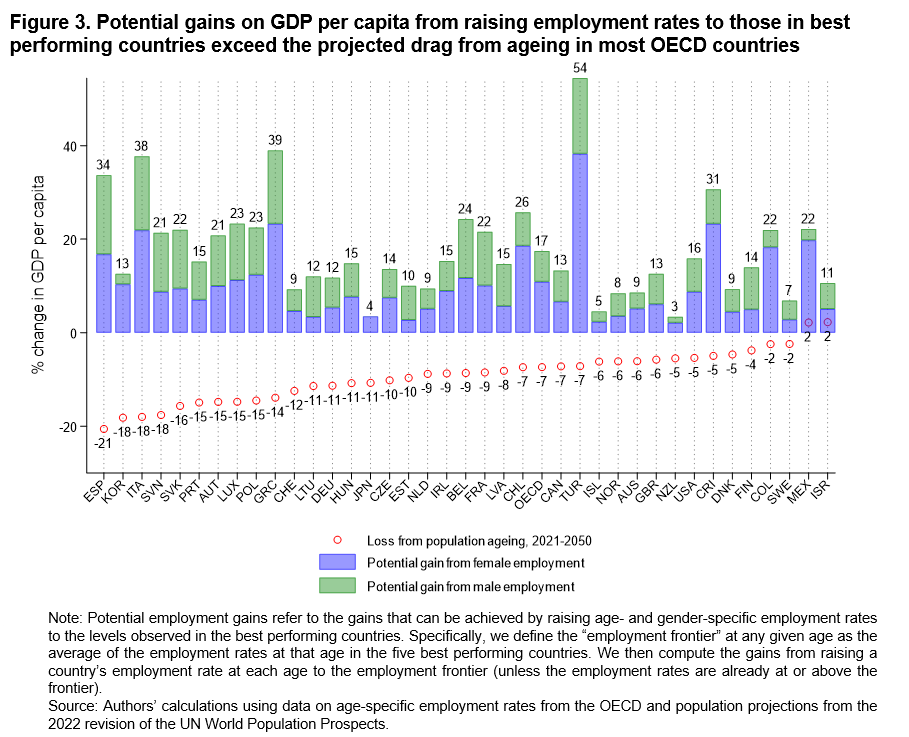

Fully offsetting the impact of ageing will in addition require raising employment in younger age groups, lifting productivity or both. High youth unemployment in some countries calls for measures to improve education and labour market matching and integration. In many countries, female employment rates are still below those of males, and can be lifted through better access to childcare and measures to tackle gender inequality. Active labour market policies can strengthen work incentives, enhance labour market matching and facilitate career transitions. In Figure 3, we compare ageing-related GDP per capita losses with potential GDP gains that countries would achieve by reaching the best performing countries’ current employment rates in every age and gender group. In most cases, this would be sufficient to offset the negative impact of ageing. In addition, the quality of jobs could be improved, by promoting better work-life balance, investing in skills, improving labour market matching and boosting productivity.

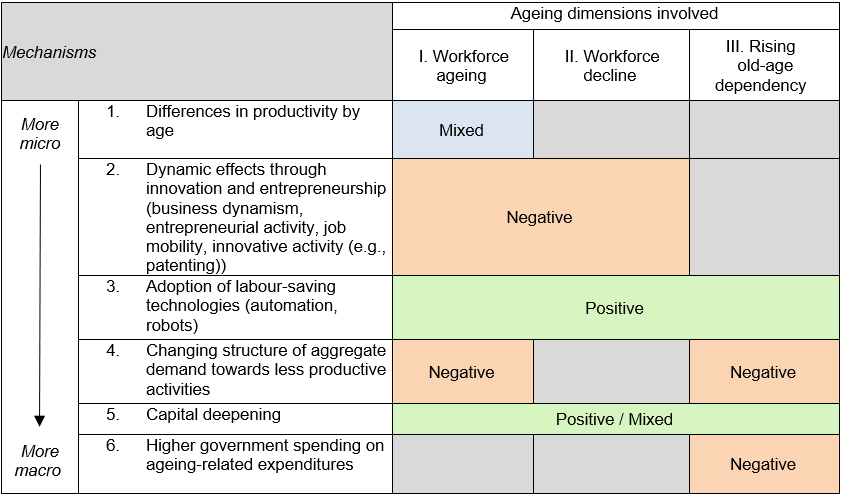

Raising output per worker would help overcome demographic headwinds. Nevertheless, population ageing itself impacts productivity growth through various micro- and macro-economic channels acting in different directions (Table 1).

Table 1

At the more microeconomic level, workers’ productivity increases with experience but may decline at older ages due to poor health or obsolescence of skills. Notwithstanding, the impact of ageing on firms’ productivity is unclear, as younger and older people work in teams and can complement each other (OECD, 2020). However, ageing tends to reduce innovation and business dynamism (Hopenhayn et al., 2022). Conversely, ageing incentivises automation, which can raise productivity. Artificial intelligence may offer new opportunities to overcome the ageing challenge, notably through alleviating labour shortages (Filippucci et al., 2024).

Ageing can also impact productivity through macroeconomic and financial developments. Savings accumulated by older generations can boost investments, but a lower bound on interest rates could prevent interest rates from falling enough, leading to secular stagnation (Eggertson et al., 2019). Risk-aversion among older people may direct savings towards conservative investments, at the expense of innovation financing. Rising age-related government spending may crowd out productivity-enhancing investments, while tax distortions may slow productivity growth, as would demand shifts towards lower-productivity services, like leisure or elderly care. This co-existence of positive and negative effects may explain that so far ageing has not been associated with lower GDP per capita (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2017).

In sum, policies can help reconcile the individual benefits from living longer with the societal challenges associated with ageing. This involves promoting healthy ageing, removing obstacles and disincentives to extending working lives, mobilising labour resources in all age groups, encouraging lifelong learning, and supporting business dynamism.

Acemoglu, D. and P. Restrepo (2017), “Secular Stagnation? The Effect of Aging on Economic Growth in the Age of Automation”, American Economic Review, Vol. 107/5, pp. 174-179, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171101.

André, C. and P. Gal (2024), “Reviving productivity growth: A review of policies”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris, forthcoming.

André, C., P. Gal and M. Schief (2024), “Enhancing Productivity and Growth in an Ageing Society: Key Mechanisms and Policy Options”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1807, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/605b0787-en.

Bernstein, S., R. Diamond, A. Jiranaphawiboon, T. McQuade and B. Pousada (2022), “The Contribution of High-Skilled Immigrants to Innovation in the United States”, NBER Working Papers, No. 30797, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w30797.

Eggertsson, G.B., M. Lancastre and L.H. Summers (2019), “Aging, Output Per Capita, and Secular Stagnation”, American Economic Review: Insights, 1 (3), 325-42, https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20180383.

Filippucci, F., et al. (2024), “The impact of Artificial Intelligence on productivity, distribution and growth: Key mechanisms, initial evidence and policy challenges”, OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers, No. 15, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8d900037-en.

Geppert, C., et al. (2019), “Labour supply of older people in advanced economies: the impact of changes to statutory retirement ages”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1554, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b9f8d292-en.

Hopenhayn, H., Neira, J. and Singhania, R. (2022), “From Population Growth to Firm Demographics: Implications for Concentration, Entrepreneurship and the Labor Share”, Econometrica, 90: 1879-1914. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA18012.

OECD (2020), Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/59752153-en.