This policy note is based on Castro, Estrada and Fernández-Dionis (2025): “Diversifying sovereign risk in the Euro-area: empirical analysis of different policy proposals,” Banco de España Working Paper 2540. The views expressed here are the sole responsibility of its authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Spain, IMF, its Executive Board, or its management, The George Washington University, CaixaBank or associated institutions.

Abstract

The 2010 sovereign crisis in the euro-area highlighted the dangers of the sovereign-bank nexus –the risk amplification effect of sovereign debt being held primarily by domestic banks. In response, important regulatory and institutional changes at the European level were put in place. Despite this, the debate on how banking regulation should account for this sovereign-bank interdependence continues today. We review the main regulatory proposals in this area and assess their impact on banks and sovereign bond markets. We conclude that these solutions could have relevant side effects for both, thus implying that non-regulatory options to complete the Monetary Union and, in particular, to issue a European safe asset, are the first order mitigating solution for this vulnerability.

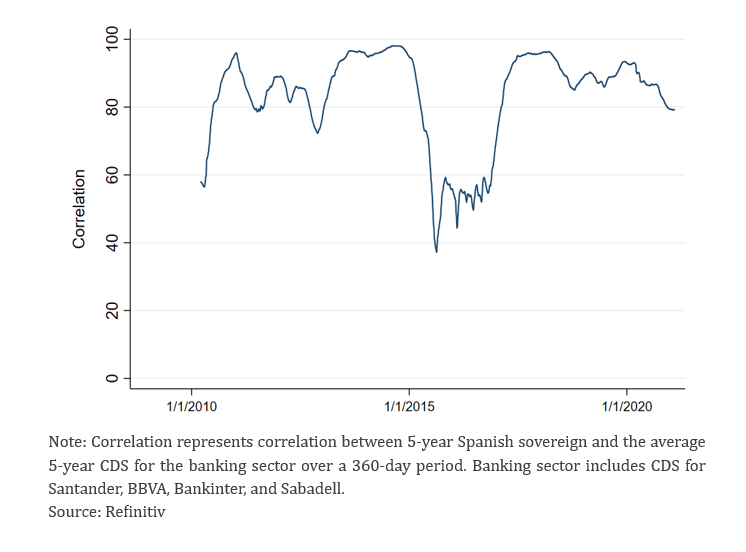

There is broad consensus that excess concentration of sovereign debt in domestic banks can be a source of vulnerabilities. In particular, in the event of a crises, it may create a feedback loop between sovereign debt and the banking sector. This amplifies overall risk through two channels. On the one hand, an expansion in bank leverage can increase the probability of bank default and subsequent bail-out, heightening sovereign risk. On the other hand, an increase in sovereign risk can reduce bank asset quality and boost bank leverage and default (Brunnermeier et al., 2016). This could be especially the case in the Eurozone Area (EA), where individual countries issue sovereign debt in an incomplete currency union where the common currency is managed by a supranational institution, the European Central Bank (ECB). In fact, as can be observed in Figure 1, the correlation between sovereign and bank CDS was close to one for Spain during the 2010-12 EA sovereign debt crisis.

Figure 1. Correlation between sovereign and bank CDS (Percentage, %)

However, sovereign debt, and safe assets in particular, are vital to the well-functioning of credit intermediation. As highly liquid assets, they are the basic collateral and are also used to cover the liquidity regulatory requirements (see, for example, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2013).

Therefore, although banking regulation could help to mitigate risks and vulnerabilities, implications for other areas should be analysed and alternative solutions considered. Specifically in the EA, where a well-publicized particularity is the relative scarcity of safe assets when compared to other developed economies due to the lack of a common public asset.

The current approach to the capital treatment of sovereign exposures in the EA in part responds to Pillar 1 requirements from Basel regulation. A special carve-out clause referenced in both Basel regulation and European Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) leads to a 0% risk-weight being applied to sovereign debt for all exposures to member states. From a market risk perspective, the framework aims to provide coverage from interest rate risk derived from the mark-to-market of sovereign debt held in the trading book. Besides, we should not forget that the leverage ratio provides a non-risk sensitive backstop to sovereign debt holdings. Under this ratio, banks must hold a minimum of eligible capital as a percentage of their total assets, including sovereign bonds.

On the liquidity front, sovereign debt top-rated (AAA-AA) is assigned the highest quality for the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR). A special carve-out exists for domestic sovereigns below AA rating which can also be included in the high-quality bucket. Furthermore, sovereign debt is also treated under the most preferential bucket under legislation that defines the net-stable-funding ratio (NSFR).

Practitioners, politicians and academics have been discussing this issue for a long time, but the debate came back to the forefront during the Covid-19 pandemic. Policy proposals can be classified into two groups. First, the non-regulatory options that relate to the completion of the currency union in the EA and, in particular, to the creation of a common safe asset. And second, the regulatory options, that aim to curtail the concentration of sovereign risk in the banking system mostly through the application of risk weights (RW) to sovereign exposures. These last proposals would affect not only the EA banking system but also those of other areas.

The non-regulatory options depart from the banking regulation framework, but they are not independent from it, as it would be advisable that these proposals go together with a specific regulatory treatment of the common safe assets proposed.

While it could be argued that the options from the previous section go more directly into the core of the problem, they require significant political agreement at the EA level. On its side, the regulatory options have been proposed at different international fora. For example, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) voiced their commitment to revisiting sovereign capital regulation; in particular, they commented on the possibility of applying concentration charges to the risk-weight treatment of sovereign debt (BCBS, 2017). However, it has been in Europe where the proposals have reached a certain level of detail.

In the second case, banks would face capital charges (or “concentration” charges), in proportion to the distance between their own sovereign debt portfolio and the “safe portfolio” which is the ECB capital key. Therefore, excess exposure and lack of exposure penalize equally. This would provide a strong incentive for banks to migrate their exposures to the ECB capital key in what is considered by the author to be the basis of market-provided European Safe Assets without joint liability.

A combination of both capital requirements as concentration charges and credit risk has also been put forward, most notably by German Finance minister Scholz in his “Position paper on the goals of the banking union”.

In this section, we have conducted an empirical analysis of the impact of the different regulatory proposals described above would have on banks’ CET1 capital ratios. We use balance sheet data from the 2023 EBA Transparency exercise disclosures on sovereign exposures and other assets.

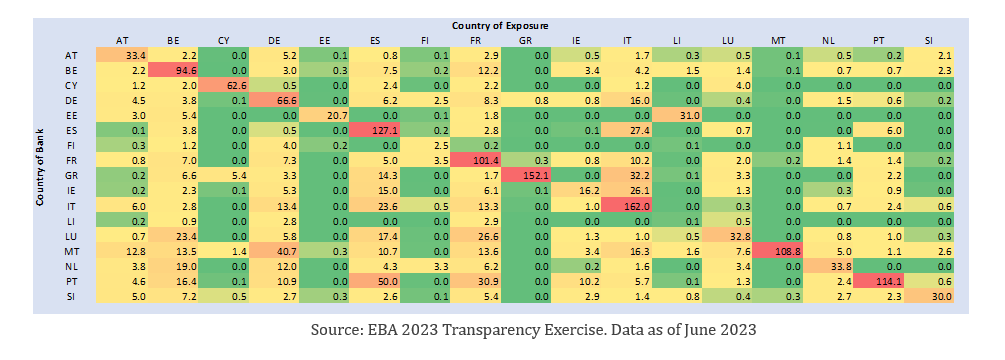

In Table 1 below we show sovereign exposure by country where the bank is domiciled (Y-axis) and the nation of exposure (X -axis). As can be seen, the diagonal, which represents the same country of origin and exposure, shows the highest level of concentration clearly highlighting home-bias among EA members.

Interestingly, the table also reveals insights into banks capital allocation decisions and subsidiary exposures. For example, Belgian and Portuguese banks have over 10 percent of their Tier 1 capital invested in French sovereign debt. Dutch, and Italian banks have over 10 percent of Tier 1 capital invested in German sovereign debt. In this sense, banks, considering cross-country ownership, seem to be both arbitraging in search for yield between sovereign debt exposures given the common zero risk-weights as well as implicitly choosing their de-facto safe asset.

Table 1. Heatmap of Sovereign Exposures as a Percentage of Tier 1 Capital (Percent, %)

To assess the potential impact of the different regulatory proposals we run a static balance sheet analysis based on the different set of scenarios:

Importantly, our analysis in this section is based on static-balance sheets and does not consider potential shifts in asset allocation from banks to respond to portfolio rebalancing. In that sense, this can be seen as a picture of how the banking system would look today before any reaction to the proposals implemented.

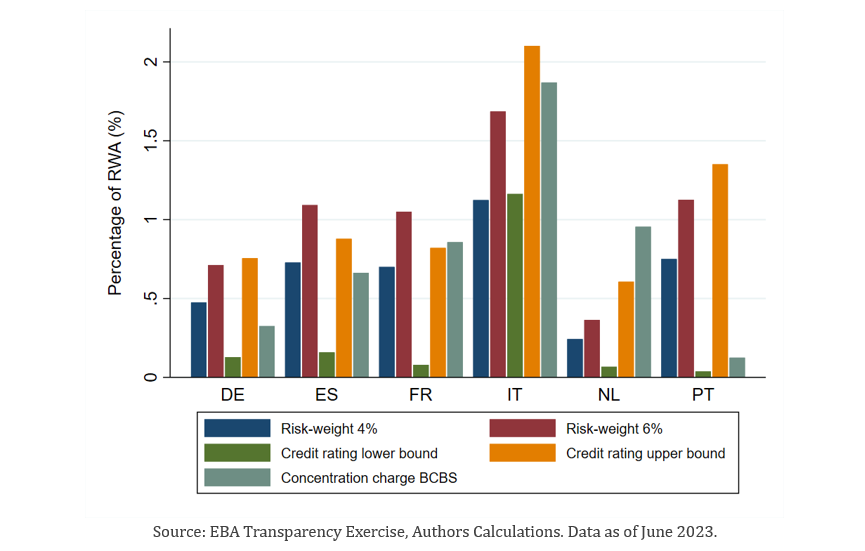

We calculate the percentage change in RW assets by type of regulatory treatment in Figure 2 below. Some general trends stand out among the 6 largest EA countries from an aggregate perspective. For countries with investment grade national debt, the lower marginal risk weight of credit rating proposal has the lowest impact. This excludes Italy, which is significantly impacted by this measure by around 1 percent of RWA, as BBB debt would have a 4 percent risk-weight. Concentration charges following the BCBS illustrative example seems to be the most punitive for the Netherlands. A flat 6 percent risk weight on national sovereign holdings has the highest impact for Spain and France while the upper bound proposal based on credit rating risk-weights has the strongest impact for Germany, Italy, and Portugal. We exclude from the chart the impact of concentration charges following Veron given its disproportionate impact compared to the rest of the measures.

Figure 2. Aggregate Impact on RWA by type of regulatory treatment of sovereign debt holdings

(As a percentage of total RWA)

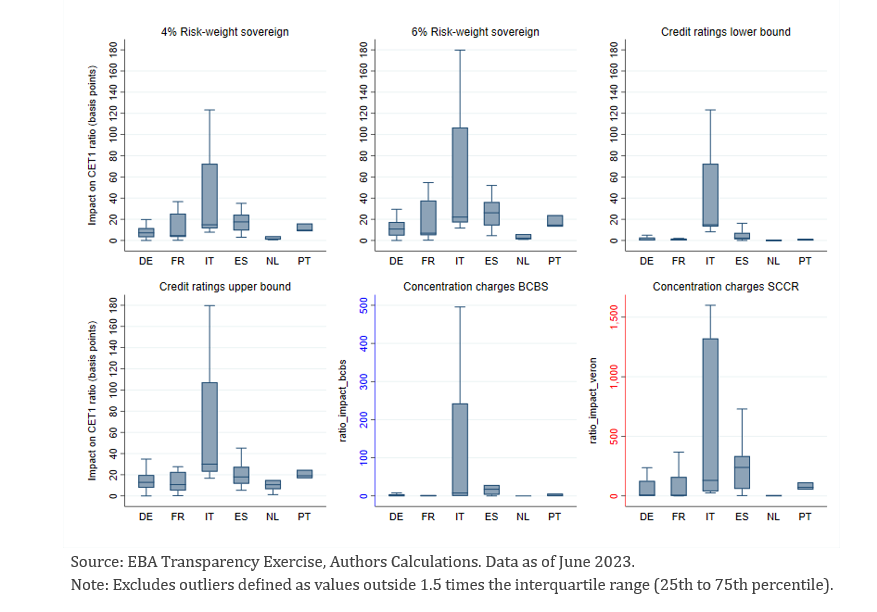

We then translate RWA impacts into CET 1 ratio in Figure 3. From a bank-level perspective, we include the main descriptive statistics (min, max, mean, 25th and 75th percentile) in the box and whiskers plot below. We see how most proposals have an individual impact between 10 to 60 basis points of CET1 with a very high dispersion between and within countries. Notably, concentration charges following BCBS has roughly 1.5 times the range of other proposals, mostly attributable to relatively stronger impact on Italian banks. Finally, adding calibrations based on Veron (2017) could lead to triple or quadruple digit impacts for many banks.

Figure 3. Bank-level Impact on CET1 by type of regulatory treatment of sovereign debt holdings

Impact on CET1 ratio (basis points)

Capital concentration charges could pose a strong catalyst for banks to rebalance their sovereign debt portfolio, affecting, consequently, the sovereign debt markets.

In this section we present a simulation exercise to illustrate these potential effects. We caveat that the results are highly dependent on initial assumptions for buying-selling conditions, but the aim is to establish empirically based ranges for the impact of the regulatory proposals in a more realistic framework where banks’ balance sheets respond to minimize the impact from regulation.

We use bond prices across 6 different maturities for European bonds to match EBA Transparency Exercise disclosure where longer-term maturities are proxied with a 10-year bond for simplicity.1 We take average bond yields across 2023 as our baseline for returns. Volatility is defined as the standard deviation of the yield during the same timeframe. We use BCBS marginal risk weights as our starting point and focus the simulation results on the top 6 EA countries. We also expand our analysis to try and simulate bank behaviour in times of stress. We do so by including a separate time series to represent periods of heightened uncertainty. Returns are proxied as the average yield in 2012, while volatility is the standard deviation of such yield during the same year.

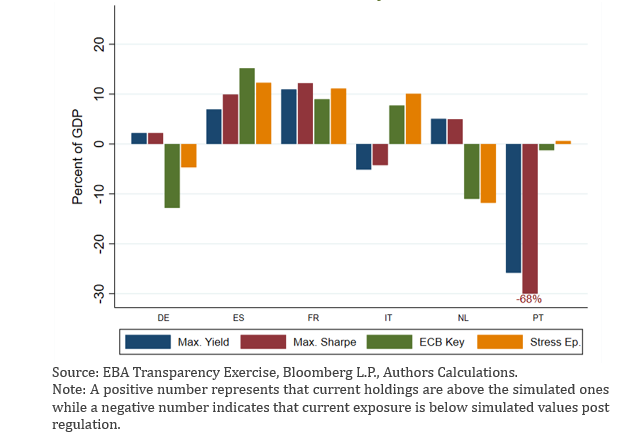

Figure 4 takes the banking system’s aggregate exposure by country as of June 2023 and subtracts the final number of holdings after the simulation. The result is scaled by each country’s GDP. A positive number represents that current holdings are above the simulated ones while a negative number indicates that current exposure is below simulated values post regulation.

By construction, bank balance sheets remain flat, so total sovereign exposure is constant before and after the simulation both at an individual level and in aggregate. Despite this, the relative and absolute country exposure changes pre- and post-regulation. In practice, this means that overall exposure from the EU banking system to Country A can change, ultimately leading to increased or decreased demand for the respective sovereign bond. From this dynamic perspective and even considering very simple reactions rules (the selling and buying algorithms explained before), impacts are considerable. From an aggregated country perspective results show:

Figure 4. Sovereign debt post simulation (Percent of country GDP)

Credit institutions invest in domestic sovereign debt for well-founded economic reasons. Specifically, these markets tend to be the deepest and broadest in each jurisdiction, making public debt an ideal instrument to maintain the liquidity reserves necessary to operate safely. Furthermore, sovereign debt default events are extremely rare, especially in the case of developed economies, which is why they tend to constitute the economy’s safest asset. This makes public debt a particularly attractive instrument in situations of uncertainty.

However, holdings of public debt on bank balance sheets can also give rise to vulnerabilities, as result of the transmission of risks between the sovereign and banks. For example, such a vulnerability materialized after the global financial crisis in what was called the sovereign debt crisis of the euro area. The interaction of the crisis with the existing institutional deficiencies within the European monetary area, particularly the lack of a common safe asset, made the sovereign-bank link especially dangerous.

The institutional reforms since then and the Basel 3 profound review of banking regulation have prevented a crisis of the same nature from being repeated in recent years despite the multiple disturbances that the financial system has suffered. However, some academics and practitioners at the European level consider that this vulnerability is still present. In this respect, there is consensus in considering that the first order solution to mitigate this vulnerability is to complete the Monetary Union in Europe; in particular, to create a risk-free common European asset that could be the European collateral. This is also a critical element for the success of the Capital Markets Union.

Other solutions, such as the proposals based on reconsidering the risk-weight treatment for sovereign bonds, could be considered second order and they could have relevant side effects both for the bond markets of several countries and the behaviour of the banks.

Alogoskoufis, S., M. Giuzio, T. Kostka, A. Levels, L. Molestina Vivar, and M. Wedow. (2020). “How could a common safe asset contribute to financial stability and financial integration in the banking union?” In: Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, European Central Bank, March. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/fie/article/html/ecb.fieart202003_02~2b34819f75.sl.html

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2013). “Basel III: The liquidity coverage ratio and liquidity risk monitoring tools.”

https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs238.pdf.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2017). The regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures. Discussion Paper, December. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d425.pdf

Brunnermeier, M. K., L. Garicano, P. Lane, M. Pagano, R. Reis, T. Santos, D. Thesmar, S. van Nieuwerburgh, and D. Vayanos. (2016). “The Sovereign-Bank Diabolic Loop and ESBies”. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 106(5), pp. 508-512. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161107.

Brunnermeier, M. K., S. Langfield, M. Pagano, R. Reis, S. van Nieuwerburgh, and D. Vayanos. (2017). “ESBies: safety in the tranches”. Economic Policy, 32(90), pp. 175-219. Previously published as ESRB Working Paper, 21. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eix004.

Craig, B., M. Giuzio, and S. Paterlini. (2019). “The effect of possible EU diversification requirements on the risk of banks’ sovereign bond portfolio”. ECB Working Paper Series, 2384. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-wp-201912

European Systemic Risk Board. (2015). ESRB report on the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures, March.

Garicano, L. (2019). “Two proposals to resurrect the Banking Union: The Safe Portfolio Approach and SRB+”. Paper prepared for ECB Conference on “Fiscal Policy and EMU Governance”, Frankfurt, 19 December. https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Two-proposals-to-resurrect-the-Banking-Union-by-Luis-Garicano.pdf

Juncker, J. C. and G. Tremonti, (2010). “Issuing E-bonds: a way to overcome the current crisis.” Financial Times, 5th December.

Matthes, D., and J. Rocholl. (2017). “Breaking the doom loop: The euro zone basket”. ESMT White Paper, WP-17-01. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340445942_BREAKING_THE_DOOM_LOOP_THE_EURO_ZONE_BASKET

Scholz, O. (2019). “Position paper on the goals of the banking union.” German Federal Ministry of Finance, November. https://prod-upp-image-read.ft.com/b750c7e4-ffba-11e9-b7bc-f3fa4e77dd47

Véron, N. (2017). Sovereign Concentration Charges: A New Regime for Banks’ Sovereign Exposures. Bruegel and Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://www.bruegel.org/report/sovereign-concentration-charges-new-regime-banks-sovereign-exposures

Wendorff, Karsten, and Alexander Mahle. (2015). “Staatsanleihen neu ausgestalten—für eine stabilitätsorientierte Währungsunion.” Wirtschaftsdienst 95, no. 9.

Maturities are 3m, 1y, 2y, 3y, 5y, and 10y.

Defined as the ratio of the current yield over its standard deviation over the past 4 quarters.