This policy brief is based on Banco de España Occasional Paper 2513. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

What are the main drivers of oil prices? We propose a simple model to disentangle demand and supply shocks in the oil market. Our findings show that global demand shocks – captured through a novel business cycle measure based on the co‑movement of real commodity prices – play an important role in explaining major oil‑price fluctuations, alongside supply shocks. We also identify an oil‑specific demand shock that improves the model’s ability to distinguish the forces at play. The model’s historical decomposition reflects key milestones in oil‑market history, offering policymakers a clear perspective on the dynamics behind oil‑price movements.

Oil prices are shaped by both demand and supply shocks, but their economic implications differ markedly. Supply disruptions – such as unexpected production cuts – raise oil prices and are classically stagflationary for oil‑importing economies: higher energy costs squeeze firms’ margins and households’ real incomes, headline inflation rises, and real activity weakens –posing a difficult policy trade‑off. By contrast, positive demand‑driven oil shocks typically co‑move with global activity, so output and inflation rise together. For oil importers, the negative impact on domestic expenditure from higher oil prices is partly offset by stronger domestic and external demand, while inflation pressures are broader and more persistent– raising the case for disinflationary policies. Weather conditions, changes in expectations, or technological change can also reshape oil‑specific demand, with distinct consequences for inflation and growth. Correctly disentangling these forces is therefore essential for calibrating policy responses.

In our analysis (Alonso‑Alvarez and Santabárbara, 2025), we modify existing approaches to better distinguish among global demand and oil‑specific demand shocks. We also introduce a new business cycle indicator, based on the co‑movement of commodity prices, to capture global demand. This perspective provides policymakers with a clear understanding of the structural drivers of oil‑price fluctuations and helps assess risks derived from alternative shock scenarios.

We propose a simple and easily updatable framework to identify four distinct shocks – oil supply, aggregate global demand, precautionary oil demand1 and other oil‑specific demand – identified via sign restrictions. The model relies on four monthly series spanning 1980 to mid‑2024: worldwide crude oil production, oil inventories, real oil prices, and a proxy for global economic activity. To approximate global inventories, we follow the approach of Kilian and Murphy (2014), rescaling US crude oil stocks by the ratio of OECD to US petroleum holdings.

A business cycle indicator

A key innovation in our methodology lies in how we capture global economic activity. Rather than relying on traditional indicators such as monthly industrial production or the “Kilian index” based on bulk dry‑cargo freight rates, we construct a global factor derived from the co‑movement of real commodity prices. While individual commodities may be driven by specific supply shocks, broad and persistent shifts across multiple commodities are more likely to signal changes in global demand. This factor thus provides a timely, forward‑looking indicator with worldwide coverage and sufficient historical depth to support robust estimation.

We construct the factor from sixteen widely traded commodities – such as crude oil, wheat, corn, soybeans, copper, and aluminium – while excluding gold and silver, which also behave like financial assets. This selection ensures sensitivity to demand conditions and avoids distortions from investor‑driven dynamics.

A factor analysis then extracts the common component across these prices. The resulting global factor explains roughly two‑thirds of observed fluctuations, offering a strong and timely signal of demand pressures.

A SVAR approach

Our model builds on the Structural Vector Autoregressive model (SVAR) framework widely used in the oil‑market literature, following the identification strategy of Kilian and Murphy (2014). Identification is based on economically motivated restrictions, with oil‑price fluctuations typically attributed to three types of shocks: global demand, oil supply, and precautionary demand.

We refine this approach by distinguishing between two sources of demand shocks: (i) global real activity shocks, arising from unexpected changes in worldwide economic activity that boost consumer spending and industrial production, and (ii) oil‑specific demand shocks different from precautionary ones, driven by factors directly affecting oil consumption such as technological advances or weather conditions. This distinction allows for a more precise characterization of oil demand and a clearer identification of aggregate demand shocks.

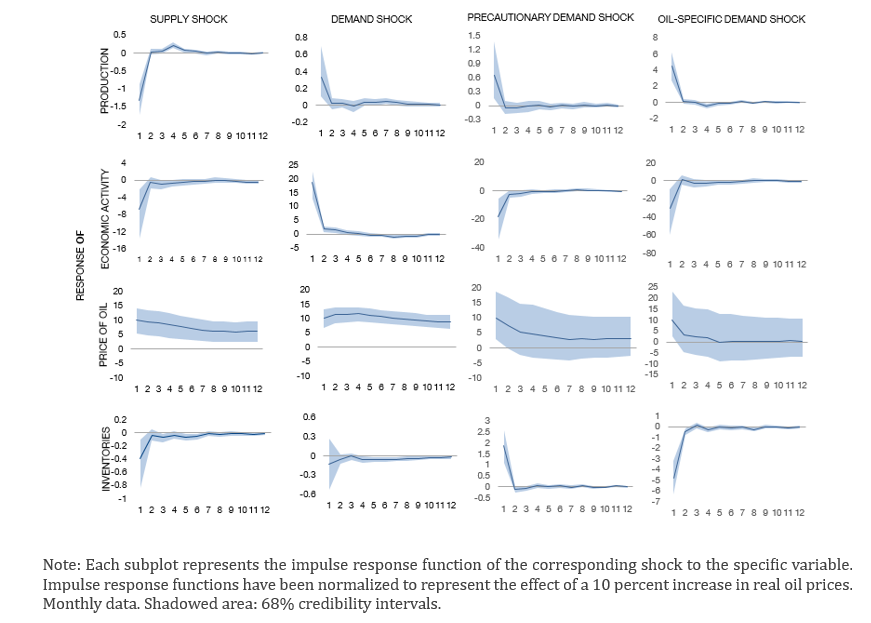

Impulse response functions behave as expected (Figure 1). Supply shocks raise prices and reduce activity, demand shocks increase both prices and production, and precautionary demand shocks lead to stockpiling and weaker activity. Importantly, supply and demand shocks have more persistent effects on oil prices – lasting up to a year – while precautionary and oil‑specific demand shocks fade within a few months.

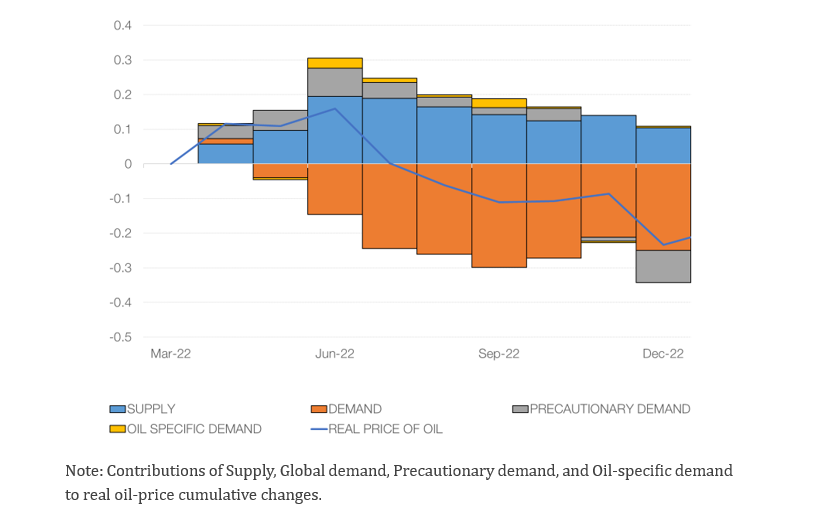

The historical decomposition highlights the evolution of oil prices across recent periods (Figure 2). In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, prices surged to USD 127 per barrel of Brent, driven by fears of supply disruptions and sanctions. Since mid‑2022, however, prices have trended downward as weak global demand and China’s lockdowns outweighed OPEC+ production cuts and temporary OECD reserve releases.

According to the model, the initial spike was largely supply‑driven, reflecting concerns over Russian exports, the impact of the embargo, and OPEC+ strategic announcements. In contrast, the decline since July 2022 stems from demand‑side factors, notably the global economic slowdown and an oil‑specific demand shock linked to China’s zero‑COVID policy (see Figure 2). This episode underscores the importance of distinguishing between global and specific oil‑demand shocks when assessing oil price dynamics.

Figure 1. Impulse response functions

Figure 2. Oil prices in response to the Ukraine war (Structural shocks decomposition)

Alonso‑Alvarez, Irma, and Daniel Santabárbara. “Decoding Structural Shocks in the Global Oil Market.” Banco de España Occasional Paper 2513 (2025).

Kilian, Lutz, and Daniel P. Murphy. “The role of inventories and speculative trading in the global market for crude oil.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 29(3) (2014): 454–478.

According to Kilian and Murphy (2014), a precautionary oil demand shock is a forward‑looking increase in the desire to hold oil –prompted by fears of future supply shortfalls – that raises today’s oil price even without a pickup in current global activity.