This policy note is based on the Bank of Italy Occasional Paper No. 968. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Bank of Italy.

Abstract

This note provides an economic analysis of the challenges facing a bail-in regime in affecting the large banks’ structure of incentives and ending the too-big-to-fail (TBTF) problem. It examines the minimum conditions for an efficient application of the bail-in, for which the rationale for mandating the involvement of the private sector in banking crises is justified and draws some examples from the EU resolution framework where these conditions may be impaired. It is indicated that the EU bail-in regulations involve complex rules and mechanisms that are accompanied in some cases by significant degrees of discretion, which could lead to uncertainties in the application of the tool and difficulties in achieving its objectives. A credible regulatory framework and a clear decision-making structure would strengthen market discipline and reduce moral hazard. Finally, from a financial stability perspective it is argued that the bail-in seems to be less viable in a banking crisis with potential systemic implications.

This note undertakes an economic analysis of the challenges facing a bail-in regime in enhancing market discipline, reducing moral hazard, and ending the too-big-to-fail (TBTF) problem. The focus is on large banks, given their peculiar role in the intermediation process and the impact of their failures on financial stability, both of which aspects justify their differentiated treatment in a crisis.

The starting point of this analysis is the ‘regime change’ determined by the global financial crisis of 2007-08 (GFC), which induced the responsible authorities to end the TBTF problem – within the post-GFC internationally coordinated regulatory repair – by recognizing that, in the case of a crisis, public bail-outs of large banks would be no longer warranted, since they have proved to create moral hazard and impair market discipline. After the GFC, new resolution regimes have been established in the G20 jurisdictions, which introduced the bail-in in the authorities’ toolkit to manage a banking crisis (FSB, 2014).

Bail-in represents a radical reconsideration of who is supposed to bear the costs of a banking crisis, since banks’ shareholders and creditors are mandated to absorb the relative losses, through a pre-defined waterfall, and support the burden of a bank’s recapitalization. In doing so, it involves replacing the implicit public guarantees to large banks balance sheets with a system of private penalties. This could reduce the amount of losses in the case of a bank failure, especially where the bail-in regime allows for earlier intervention and closure than a bail-out mechanism, eliminating in principle the TBTF subsidy (Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2015).

Some authors have considered the bail-in as the modern alternative to the two traditional tools to address banking crises that were famously described by Walter Bagehot in his influential book Lombard Street, where he distinguished two alternatives: i) to provide central bank liquidity for illiquid banks and ii) to wind down insolvent ones. Bail-in is a ‘third way’, in the sense that it seeks to self-insure banks, so that a rescue with public money becomes unnecessary (Ringe, 2016).

While bail-in improves the policy mix at the authorities’ disposal in a crisis, it is a tool that authorities have tended to manage with care. This explains why in the post-GFC regulatory reforms a significant layer of supervisory discretion has been included to complement the automaticity of the rules. In doing so, the post-GFC reforms have considered the historical experience, which shows that the responsible authorities have always used significant discretion in managing and resolving banking crises, with a record of positive outcomes on average. However, it has to be recognized that if these degrees of discretion are framed in complex rules and mechanisms, there is the risk that their cumulative effects may create severe uncertainties.

The economic theory says that market discipline is enhanced, and moral hazard is reduced if investors can foresee the price of their capital instruments and anticipate the expected losses in the case they are bailed-in with a reasonable degree of certainty. Accordingly, investors would price a bank’s equity capital based upon only the default probability embedded in the bank’s assets and not with a view to distorting implicit public guarantees. If these conditions fail, the original objectives of the bail-in may be impaired (Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2014).

Public bail-outs have been considered for decades a rational reaction to avoid the destabilising effects of a large bank’s failure. However, the use of taxpayers’ money may undermine financial stability if it is conducive to unsustainable public finances. Moreover, the recourse to bail-outs allows market participants to predict this kind of decision, so as to include an implicit government’s guarantee in the price of bank capital, thus reducing large banks’ default probability. Such implicitly guaranteed banks show lower risk premiums and collect capital at lower prices.

Several empirical studies confirm these distorted market prices mechanisms (Ueda and Weder-Di Mauro, 2012). In this context, bank equity holders and managers have the incentives for an excessive risk-taking behaviour (moral hazard), which ultimately leads to an increased level of leverage, and to largely inefficient investment decisions. Market discipline is hampered in the case bank’s risk bearing capacity is not the guiding criterion for their capital market pricing (Brandao-Marques et al., 2013).

After the GFC, to limit the systemic effects stemming from a large bank’s failure, while avoiding moral hazard and enhancing market discipline, authorities mandated a regulatory framework in which the private sector could be requested to bear the costs of these failures. These regulatory regimes have been designated in such a way to undo any government implicit subsidy and connect credibly banks’ funding to the level of risks incurred, in order to reduce the excessive risk taking, induced by moral hazard (Gordon and Ringe, 2015).

The bail-in tool provides a mechanism to return an insufficiently solvent bank to balance sheet stability, at the expense of its shareholders and creditors, without the need of external (i.e., publicly funded) capital injection. (Gleeson, 2012).

For this tool to work efficiently, the condition is that the private sector involvement should not undermine the viability of the essential functions of the resolved bank. Only under these conditions, bail-in preserves the incentives attributed to the insolvency proceedings, but avoids overly disruptive effects, preventing liquidity stress, and averting file sales and ultimately the disorderly liquidation of financial contracts. More specifically, bail-in is an instrument to facilitate a large bank’s smooth recapitalization, since it leaves the bank’s critical functions untouched, thus preserving the bank’s existing degree of interconnectedness, its complex group structure and cross-border activities (Sommer, 2014).

The contribution of the private sector to bear the costs of a banking crisis can act as a crisis accelerator, since the haircuts imposed on the investors’ financial instruments may make harder for troubling banks to refinance themselves, thus increasing pro-cyclical systemic crisis effects. If investors base their decisions on full rationality, bail-in cannot trigger a systemic crisis, since it has the capacity to limit the loss bearing to a sub-set of markets’ participants.

However, the hypothesis of full rationality as a guiding criterion for the decisions of the economic agents is purely theoretical. With the more common hypothesis of bounded rationality, runs may occur even if investors have no reason to believe that their bank is in trouble. Drawing from the US experience of 2007-08 financial crisis, Avgouleas and Goodhart (2014) have stressed how the bail-in mechanism may bring irrational fears that similar haircuts can be equally imposed on creditors of other (similarly conducted) banks, thus inducing investors to run.

The diffusion of investors panic can be mitigated if there is in the system a sufficiently large layer of long-term – non-runnable –high quality and easy to be bailed-in capital that credibly ensures about the boundaries of the private sector involvement in a crisis. The objective is that the other creditors should be reassured that the haircut tool will not reach their claims as well.

Under bounded rationality and with an unclear scope and possible extension of the crisis, only the existence of a second line of defence – in the form of a credible government backstop – has the potential to arrest panic among market participants. Even a credible private sector involvement requires a strong public backstop for all runnable contracts on the liability side of banks’ balance sheet; on the contrary, it can accelerate incoming crises.

A key condition for an efficient application of a resolution tool refers to the careful design of its regulatory framework. In the case of the bail-in, a clear and coherent legal framework is essential, and needs to establish an appropriate balance between the rights of private stakeholders and the public policy interest in preserving financial stability. This legal certainty acts as a precondition for the credibility of the bail-in regime, particularly in a cross-border context.

The bail-in regime may reach more efficient outcomes than a regime based upon government guarantees and bail-outs, if investors who perceive that bank capital instruments have become more risky are in a condition to decide accordingly. This means that bail-in may not produce pro-cyclical effects if investors can calculate and price correctly the bail-in risk, that is the default probabilities, the exposures at default, and the associated loss given default, so that their actual results do not diverge materially from their ex ante expectations. In this case, investors in financial instruments subject to bail-in will not be discouraged and will continue funding other banks.

To achieve this outcome, it is important that the resolution framework should not add additional layers of uncertainty, which comes on top of information problems investors naturally face (Gorton, 2009). This can be achieved if the regulatory framework allows market participants to predict the multitude of decisions that authorities have to make immediately before or in resolution. If investors make mistakes, risk premiums are distorted, and the market discipline may send wrong incentives, with abrupt adjustments across markets.

Furthermore, bail-in can limit bank runs, and contagion, if it is credible. For this reason, it is necessary to ensure that the banks have a sufficient amount of bail-inable liabilities, to achieve the internal recapitalization in an orderly, effective and timely manner.

Predicting the precise conditions and circumstances for a bank’s failure and the actions to be activated by the resolution authorities is tied to the elements of the so-called Knightian uncertainty, whose distinctive features signal a number of elements and aspects of the real world, include those of the banking crises, which are not susceptible to be measured with precision (Trapanese, 2022).

A consistent strand of the economic literature has raised arguments in favor of an implementation of resolution tools with an acceptable level of discretion, within a strategy pursued on a case-by-case basis by the resolution authority (Hellwig, 2021). This means that there exists a tension that cannot be entirely eliminated between ex post efficient outcomes and the inefficient ex ante effects of uncertainty, which may undermine the objectives of a bail-in regime, as an adequate mechanism for ensuring that the private sector bear the costs (or part of them) of a banking crisis.

However, the discretionary elements in the resolution framework that impact on the predictability of the private sector involvement in a banking crisis should be limited to the necessary, in order to shield the investors in bail-inable instruments from the negative consequences of the inevitable unpredictability of bank resolutions outcomes. For example, Zhou et al. (2012) recognize the importance to minimize the uncertainty generated by a discretionary use of bail-in powers, in order to avoid surprising and negative effects across markets participants.

The EU bail-in regime appears to be highly prescriptive. However, this does not necessarily imply rules prescribing with precision the outcomes of the resolution actions. A possible explanation points towards very complex rules and mechanisms with many exceptions and restrictions, which require the use of a significant amount of discretion in the decisions to take by responsible authorities.

This could imply that – once combined with the necessity to coordinate the several layers of authorities and private parties in the EU – the necessary assessments are difficult to make and are subject to varying standards and approaches. These uncertainties could create a situation where the achievement of the post-GFC policy objectives assigned to bail-in (i.e., enhanced market discipline, reduced moral hazard, and protected state’s fiscal position) could be impaired (Troger, 2018).

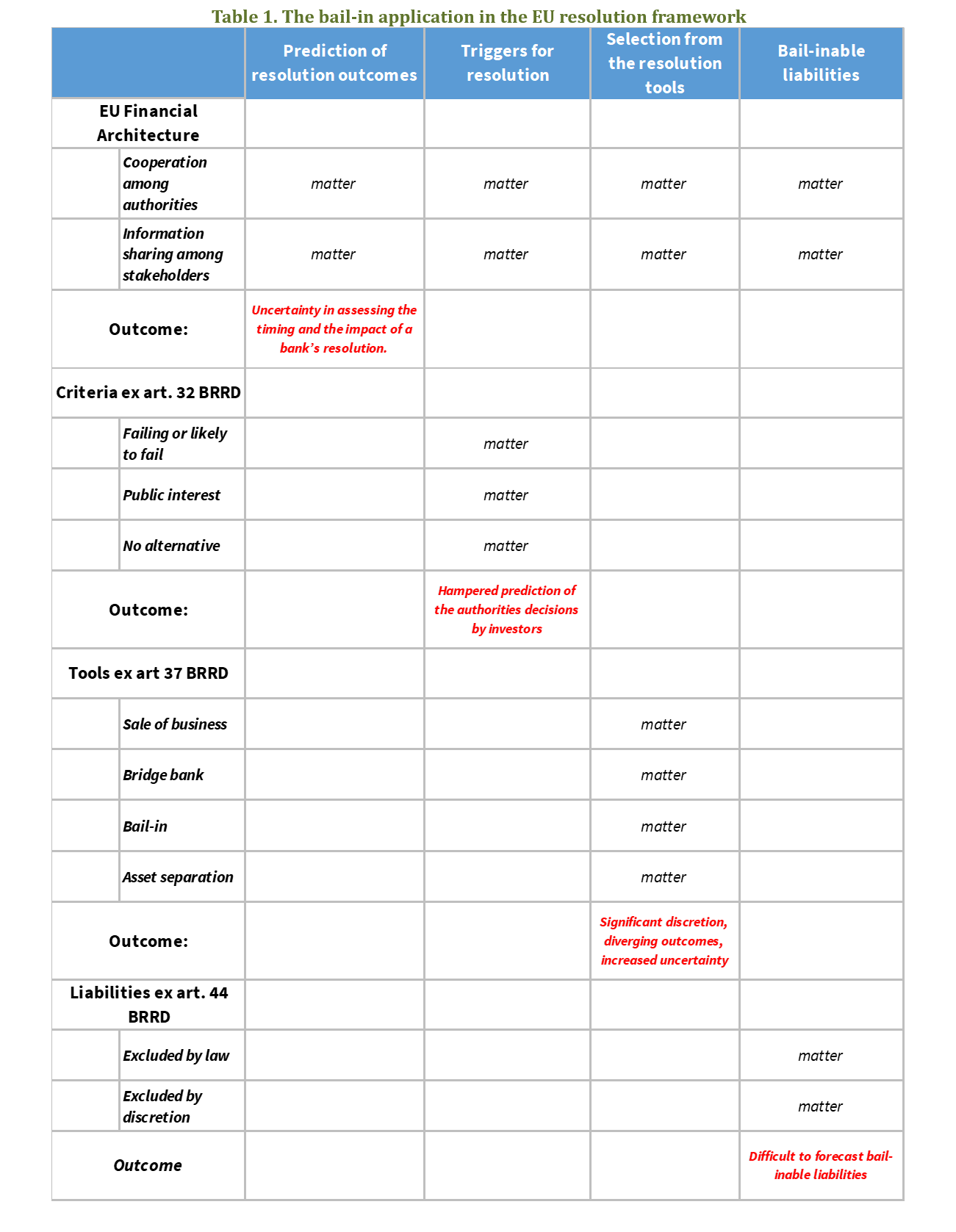

Some examples can be drawn from the EU resolution framework where the minimum conditions for an efficient bail-in regime, as outlined previously, might not be achieved. They belong to the following areas:

Prediction of resolution outcomes. In the application of the bail-in, the prediction of the outcomes is complicated, because its proper functioning depends on the close cooperation and information sharing among authorities belonging to different jurisdictions. To ensure an adequate accuracy of any calculation on the implied default probabilities and loss given default, investors have to know who makes the final decision in each step of the procedure. This situation adds significant uncertainty in assessing the timing and the impact of a bank’s resolution.

Triggers for resolution. The condition for the activation of the bail-in is that a formal resolution proceeding is triggered by the resolution authority, who decides based upon three criteria.1 Each of these criteria requires complex supervisory or resolution actions, whose results cannot be calculated with precision ex ante. In this context, the prediction of the outcomes by investors and markets could be hampered. Enhanced certainty can be achieved over time, if there is a reasonable number of cases where the application of the criteria has been done consistently. This can turn out to be particularly difficult in the EU, given the overlap of competences among authorities and the lack of transparency for no-action decisions.

Selection from the resolution tools. Resolution authorities may choose the resolution tools that are more coherent with the resolution strategy adopted for each individual bank from a set of tools defined by law.2 This means that even in a resolution the involvement of the private sector is not mandatory, given that the resolution authorities may opt to manage the crisis applying the other tools. In this respect, resolution authorities have a significant level of flexibility as to the choice of the tool to use in a crisis scenario. In this context, the lack of the minimum (theoretical) conditions for an efficient bail-in regime (legal certainty, and prediction of outcomes by investors) matters, given that the degrees of discretion available to authorities may lead to diverging outcomes, thus increasing uncertainties for market participants.

Liabilities exempt from bail-in. In the EU resolution framework, there are liabilities that are either exempt from bail-in directly by law, or are excluded in exceptional circumstances at the discretion of the resolution authorities. In the first case (article 44.2 of the BRRD), their identification seems to be not straightforward, because some of the terms used require an interpretation and an in-depth knowledge of the bank’s business model, organizational structure and investments decisions. The same holds for the liabilities excluded by the authorities (article 44.3 of the BRRD). It could be difficult to forecast, at the time of the investment, whether certain liabilities are distributed in a way that their bail-in would lead to run-like scenarios or impede the continuity of critical functions of the bank.

The following table indicates the main issues, drawn from the EU resolution framework, potentially impairing an efficient implementation of a bail-in decision on the part of the authorities in the case of a banking crisis. These issues are built following the lines of reasoning outlined in this policy note. It shows that the EU bail-in involves complex mechanisms and rules accompanied by large degrees of discretion. Their cumulative effects could determine as an outcome increased uncertainties in the application of the tool and difficulties in achieving its original objectives.

The ability of bail-in to handle a system-wide banking crisis has not been tested so far. In the case of a systemic crisis, it could be unrealistic to believe that bail-in can be activated on a magnitude that allows absorbing the losses or ensuring the recapitalization needs of all the involved banks simultaneously. Similar arguments hold also in the case of an individual failure affecting any of the largest and systemic banks.

These arguments have been at the centre of the decisions taken in the post-GFC years by the responsible authorities, when they have been faced with the issue to apply (or more often not to apply) the bail-in tool (for an extensive review of the several cases incurred in the EU, see Ventoruzzo and Sandrelli, 2020). The last episode in order of time has been the crisis of the Credit Swiss in 2023: it has shown all the difficulties and problems that have to be dealt with in the case of a possible application of the bail-in to a large and systemic bank. For the above considerations, the bail-in tool seems to be relatively more viable in the case of a crisis affecting a bank whose dimension and risk profile do not give rise to systemic concerns.

We have learnt from history that in the case of a systemic crisis the decisions taken by governments to avoid any public backstop to the financial system usually tends to aggravate the consequences of the crisis. The resolution of a large and systemic bank would still require a credible fiscal backstop. The EU framework for crisis management still misses a financial stability facility/exemption, aimed at overcoming the rigidities of the framework in the case exceptional circumstances threaten the EU financial stability. This feature, coupled with the absence of a true European deposit insurance system, makes the EU crisis management framework still incomplete (Trapanese et al., 2024).

In this respect, it could be recalled that it is not always true that the interests of tax-payers are in all cases impaired by the governments interventions. Their indirect costs, in terms of reduced market discipline or enhanced moral hazard, have to be assessed against their indirect benefits, such as the economic and financial stabilizing effects from a large bank’s rescue. Both costs and benefits cannot be measured with accuracy ex ante. The taxpayers’ estimated losses are higher at the point of the crisis, but it is not uncommon that the investments of tax-payers in bank capital may be reversed overtime. The potential losses for the public participation in bank recapitalization may turn into substantial gains, as the economic conditions improve and the value of the bailed-out bank increases on the markets (Hertig, 2012; Dewatripont, 2014).

This note has shown that the objectives of the post-GFC bail-in approach to bail-in (enhancing market discipline, reducing moral hazard, and protecting public finance) can be achieved to the extent market participants can make informed predictions about the authorities’ reaction function in a crisis, and foresee the risk of their capital instruments being written-off or converted with reasonable certainty.

In the EU the bail-in is based upon a regulatory framework where the automaticity of the rules is complemented by a significant discretion. If these degrees of discretion are framed in a decision-making process based upon complex mechanisms and rules, there could be uncertainties in the application of the bail-in and difficulties in the achievement of its original objectives.

From a functional perspective, it is shown that the bail-in is supposed to work efficiently, if its implementation does not create the conditions for mounting threats to the stability of the financial system as a whole.

Avgouleas E., and Goodhart C., (2014), “A Critical Evaluation of Bail-ins as Bank Recapitalisation Mechanisms”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 10065.

Avgouleas E., and Goodhart C., (2015), “Critical Reflections on Bank Bail-ins”, Journal of Financial Regulation, Vol. 1, Issue 1, March.

Brandao-Marques L., Correa R., and Sapriza H., (2013), “International Evidence on Government Support and Risk Taking in the Banking Sector”, IMF Working Paper No. 94

Dewatripont M., (2014), “European Banking: Bailout, Bail-in, and State Aid Control”, International Journal of Industrial Organization, Vol. 34.

FSB, (2014), “Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions”, October.

Gleeson S., (2012), “Legal Aspects of Bank Bail-ins”, LSE Financial Markets Group Paper Series, Special Paper No. 205.

Gorton G., (2009), “Information, Liquidity, and the (Ongoing) Panic of 2007”, American Economic Review, Vol. 99.

Gordon J. N., and Ringe W. G., (2015), “Bank Resolution in the European Banking Union: A Transatlantic Perspective on What It Would Take”, Colombia Law Review, Vol. 115.

Hellwig M., (2021), “Twelve Years after the financial Crisis – Too-big-to-fail is still with us”, Journal of Financial Regulation, January.

Hertig G., (2012), “Governments as Investors of Last Resort: Comparative Credit Crisis Case-Studies”, European Corporate Governance Institute, Law Working paper, No. 187, January.

Ringe W. G., (2016), “Bail-in between Liquidity and Solvency”, University of Oxford, Legal Research Paper Series, Paper No. 33.

Sommer J. H., (2014), “Why Bail-in? And How?”, FRBNY, Economic Policy Review, December.

Trapanese M., (2022), “Regulatory complexity, uncertainty, and systemic risk”, Bank of Italy, Occasional Papers Series, No. 698, June.

Trapanese M, Albareto G., Cardillo S., Castagna M., Falconi R., Pezzullo G., Serafini L., and Signore F., (2024), “The 2023 US banking crises: causes, policy responses, and lessons”, Bank of Italy, Occasional Papers series, No. 870, July.

Troger T. H., (2018), “Too Complex to Work: A Critical Assessment of the Bail-in Tool under the European Bank Recovery and Resolution Regime”, Journal of Financial Regulation, Vol. 4.

Ueda K., and Weder-Di Mauro B., (2012), “Quantifying the Value of the Subsidy for Systemically Important Financial Institutions”, IMF Working Paper No 12/128.

Ventoruzzo M., and Sandrelli G-. (2020), “O Tell Me the Truth about Bail-in: Theory and Practice”, Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship, & Law, Vol. 13, Issue 1.

Zhou J., Rutledge V., Bossu W., Dobler M., Jassaud N., and Moore M., (2012), “From Bail-out to Bail-in: Mandatory Debt Restructuring of Systemic Financial Institutions”, IMF Staff Discussion Note, No. 12, April.

In the EU framework, these three criteria are the following: i) the bank is failing or is likely to fail; ii) there is no (private or public) alternative to the bank’s failure; iii) resolution pursues the public interest better than an ordinary insolvency procedure. The article 32 of the BRRD provides the detailed rules governing these conditions.

The resolution tools foreseen in the BRRD (article 37) are the following: the sale of business tool; the bridge institution tool; the asset separation tool; the bail-in tool. Resolution authorities may apply the resolution tools individually or in any combination.