The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

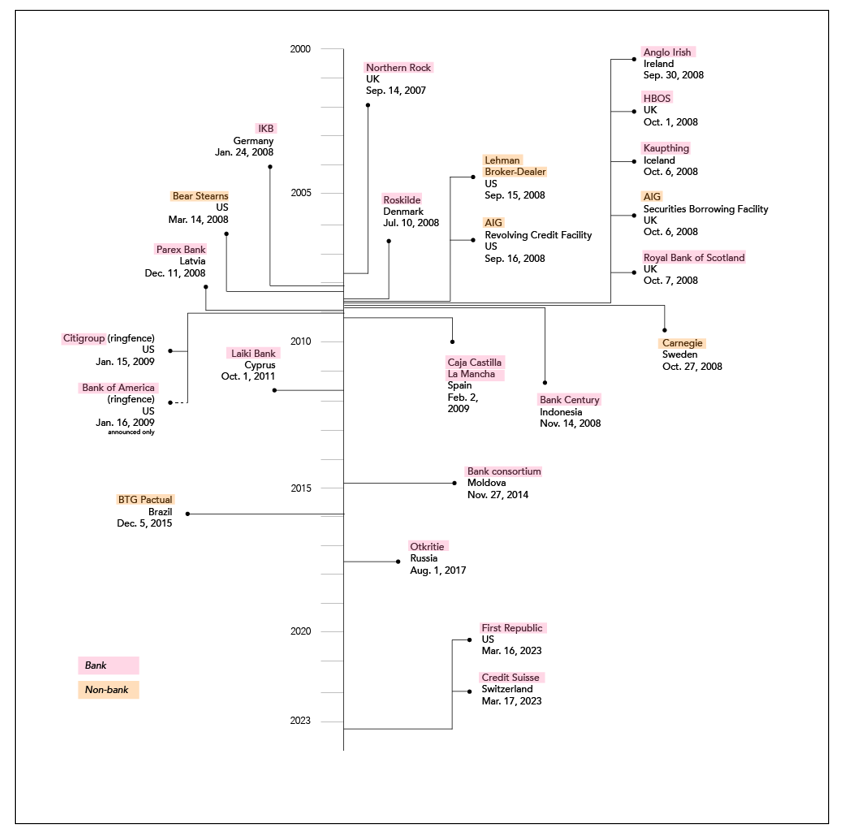

In a new paper, Ad Hoc Emergency Liquidity Programs in the 21st Century,1 we survey 22 case studies of 21st century instances when financial crisis-fighters implemented ad hoc emergency liquidity (AHEL) interventions: those designed to target emergency liquidity to a particular institution that the authorities believed was systemically important. Liquidity crises should be viewed as the manifestation of the market’s assessing the firm as nonviable. For that reason, central banks should provide AHEL assistance only to institutions that they have deemed viable or that they have committed to make viable through additional policy interventions, such as a capital injection or merger. Despite often-sizable AHEL assistance, in none of the studied cases did liquidity provision alone prove a “cure” to the run on the institution; additional, structural balance-sheet interventions were always needed. Following this insight, crisis-fighters can use these later interventions to manage the moral hazard concerns. AHEL programs, by contrast, should simply focus on providing sufficient liquidity to get the institution through its acute crisis phase.

Figure 1. Timeline of Surveyed Cases of Ad Hoc Emergency Liquidity Programs

Source: Kelly, Arnold, Feldberg, and Metrick 2025.

When faced with sudden market demands for liquidity, central banks typically prefer to provide it through open market operations or broadly available liquidity programs. However, such programs are not always sufficient to provide the desired amount of liquidity to individual financial institutions suffering from a viability crisis. In those cases, an ad hoc emergency liquidity (AHEL) program is needed. Like what might be commonly referred to as a solvency crisis, we use the term “viability crisis” to describe a situation in which markets have lost confidence in a firm’s ability to continue as a going concern—and either do not expect authorities to intervene to save it or do not expect such interventions to restore the institution’s going-concern status.

Most academic and policy discussions group together different types of “emergency liquidity assistance” programs, addressing ad hoc and broad-based emergency liquidity (BBEL) collectively.2 Our paper focuses specifically on the design of targeted, ad hoc emergency liquidity (AHEL) programs.3

Crisis-fighters typically resort to an AHEL program quickly when addressing the acute, or “panic,” phase of a crisis at a troubled financial firm; AHEL interventions are relatively quick to implement and can help the firm meet the demands of a run. However, authorities should not expect an AHEL program—however it is designed—to prevent or solve the chronic, or “debt overhang,” phase of a firm’s crisis. Chronic problems demand structural responses, such as capital injections, liability guarantees, balance sheet restructurings, or orderly resolutions. Crisis-fighters often suggest that their intent in providing emergency liquidity is to prevent an institution that is “illiquid but solvent” from tipping into insolvency, but liquidity crises are rare in the absence of deeper solvency or viability concerns.

Illiquidity in the case of an individual institution is almost always the manifestation of the market’s assessment of the institution’s nonviability as a going concern.4 An assessment of nonviability may simply reflect a view that the firm is insolvent based on depressed market valuations, rather than book valuations. In other cases, it may reflect a view that the firm, solvent or not, no longer has a sustainable business model—perhaps due to macroeconomic developments; competitive dynamics; regulatory problems; or the loss of key customers, staff, or important licenses or charters.5

Indeed, in none of the surveyed cases did the illiquidity simply pass and leave the AHEL borrower’s balance sheet relatively unchanged after the firm received liquidity assistance. In every case, the troubled firm required significant balance sheet restructuring, usually with further official support. Crisis-fighters should design ad hoc emergency liquidity programs to buy time to address a firm’s fundamental viability issues through such restructuring measures. They shouldn’t expect liquidity programs to help a firm avoid insolvency by addressing illiquidity. Other policy interventions will almost certainly be necessary and should be rolled out as expeditiously as possible following the AHEL intervention. Recognizing that AHEL assistance can meet the problems of the institution’s acute crisis phase only, rather than solve its chronic issues, policymakers can spend less of their focus on managing moral hazard when designing AHEL programs. Moral hazard can be addressed in the more structural policy responses that will need to follow; AHEL programs should focus on providing sufficient liquidity, particularly if the institution has been deemed viable (inclusive of the impact of other forthcoming interventions).

Modern crisis-fighters regularly return to Walter Bagehot’s famous 1873 dictum on the appropriate role for a central bank during a crisis, which is typically stated pithily as “lend freely, against good collateral, at a penalty rate.” Many authors have also either ascribed a “solvency” requirement to Bagehot6 or added it themselves, updating the dictum to something along the lines of “lend freely to solvent counterparties, against good collateral, at a penalty rate.” It has thus long been a common view among financial authorities that central banks should provide liquidity only to firms that are “solvent but illiquid.”7

Yet, when possible, central banks in the case studies we surveyed often did not constrain themselves to thresholds of literal, or accounting, solvency when confronted with the potential for systemic failure. Rather, they tended to evaluate more broadly the systemically important financial institution’s viability as a going concern, inclusive of the effect of the additional intended policy interventions. Still, regulations and statutes tend to emphasize “solvency,” even in cases where central banks took a broader view of viability.8

During a crisis, market participants may assess an accounting-insolvent firm to be viable as a going concern if they trust its management’s business model or trust the authorities to provide sufficient support. They may also assess an accounting-solvent firm to be nonviable in the absence of those things.9

From the authorities’ perspective, they need to consider whether their resources and available tools will be sufficient to restore a firm’s viability as a going concern. As a Bank for International Settlements (BIS) working group writes in a 2017 paper,

While there is no formal definition of viability, the concept requires the assessor to look beyond the current valuation of the firm’s assets and liabilities and to consider the firm’s and/or relevant authorities’ ability to reestablish the firm as a going concern, possibly with the help of [liquidity assistance] and after adjustments in its business model.10

Practically speaking, accounting solvency is particularly difficult to evaluate in real time when considering the speed of a crisis, the delays and uncertainties of financial accounting, and the endogeneity of asset and franchise values to crisis responses.11 Moreover, even if the central bank is able to ascertain solvency, but the firm is nonviable, the central bank may still realize the risks typically ascribed to lending to insolvent institutions. That is, lending to nonviable firms increases the likelihood, relative to lending to an insolvent-but-viable firm, of the central bank’s facing policy drawbacks such as: experiencing losses; reallocating losses between stakeholders; needing to take possession of too much, or difficult-to-manage, collateral; adding stigma to other firms taking liquidity assistance; or effectively drifting into fiscal policy or other political decision-making.12 By contrast, focusing on a systemically important firm’s long-term viability—assuming whatever government support is financially and politically feasible—can avoid those costs by resulting in loans only to firms that are truly going concerns.

Policymakers should avoid mistaking liquidity stress as the cause rather than the effect of a firm’s problems—which would also cause an assessment that backstop liquidity is all that is required. Several AHEL interventions in our survey demonstrate instances where crisis-fighters sized the AHEL assistance to effectively cover all possible short-term outflows, yet counterparty and customer outflows continued until the authorities took additional measures. Clearly, even assuring repayment of all maturing obligations is not a sufficient condition to stop runs.13

Where we do find success for AHEL interventions is in buying time to implement the more structural responses necessary to address an institution’s viability concerns—such as capital injections, liability guarantees, balance sheet restructurings, and the like—which often require relatively more planning or time-consuming measures.

Given this context, policymakers should reconsider whether all policy trade-offs associated with financial institution rescues must be embedded in the design of the AHEL program itself. In practice, rescue terms intended to mitigate moral hazard are more effectively imposed through the structural policy interventions that follow. The case studies examined in the paper frequently show that when AHEL program terms were initially established as overly punitive because of moral hazard concerns, policymakers were later forced to loosen those terms to provide an effective bridge to the more structural policy responses that followed.

Moreover, when a firm already has access to a standing liquidity facility, the very need for an AHEL program suggests that the standing facility’s terms are too restrictive to be effective to provide enough liquidity to the borrower. Thus, the AHEL intervention must, by design, be relatively expansive compared to standing, or other broad-based, facilities. Returning to Bagehot’s dictum, which advises that when broad-based liquidity provision is needed, central banks should “lend freely, against good collateral, at a penalty rate,” it seems only “lend freely” survives in practice when designing effective AHEL interventions.

A penalty rate, often meant to discourage moral hazard and encourage repayment as financial conditions normalize, may actually accelerate the run on a targeted firm, draining its financial resources faster and further eroding the confidence of the market and the rating agencies. In such situations, imposing penalty pricing may undermine the very purpose of the intervention. Given that AHEL interventions work effectively only as bridges to more structural policy responses, it behooves crisis-fighters to save the more punitive or costly design features for those later-stage responses, when the institution has been stabilized as a going concern.

In the AHEL setting, the central bank (or other lender14) often interprets collateral requirements as flexibly as necessary to get sufficient liquidity to the firm in distress. However, such departures from standard practice should not be interpreted as the ubiquitous disregard of caution by desperate crisis-fighters. Rather, if the AHEL intervention is known to be a bridge to other policy responses, those policies can themselves provide additional security. For instance, if the AHEL-receiving institution is going to merge with a healthy institution, the central bank can consider the strength of the acquirer’s balance sheet. Or, if the government is organizing a capital injection, the central bank can consider such incoming funds when evaluating the borrower’s financial condition and ability to repay. The risk of such designs, to be sure, is in the level of uncertainty about the forthcoming additional policy responses.

Establishing an AHEL program with the hope that the institution can avoid insolvency if it is saved from illiquidity will almost certainly lead to wasted time or lost credibility for crisis-fighters. An effective AHEL program is one that is followed as expeditiously as possible by additional policy measures to address the borrower’s chronic problems and restore it to viability. Given that additional policy measures are to follow, the terms of an AHEL program can focus on providing sufficient funding and be less bound by concerns of moral hazard.

The received wisdom on Bagehot’s dictum assumes that the restrictions of good collateral and penalty rates are designed so that the central bank functions as a backstop to systemic liquidity demands. AHEL programs are not backstops like their discount window and BBEL program brethren; they must provide the funds needed to meet the run on the systemic institution.

This paper is available in the Journal of Financial Crises (Vol. 7: Iss. 1, 57–106). s

A welcome exception is a 2016 International Monetary Fund (IMF) paper that, similar to our focus on AHEL programs, centered on what its authors call “idiosyncratic support”; see Dobler, Marc, Simon Gray, Diarmuid Murphy, and Bozena Radzewicz-Bak. 2016. “The Lender of Last Resort Function after the Global Financial Crisis.”

For those interested in broad-based liquidity programs, see the sister Yale Program on Financial Stability papers on BBEL interventions and market-support liquidity interventions: Wiggins, Rosalind Z., Sean Fulmer, Greg Feldberg, and Andrew Metrick. 2023. “Broad-Based Emergency Liquidity Programs”; Rhee, June, Lily S. Engbith, Greg Feldberg, and Andrew Metrick. 2022. “Market Support Programs: COVID-19 Crisis.”

For related recent literature, see Baron, Matthew, Emil Verner, and Wei Xiong. 2021. “Banking Crises without Panics”; Correia, Sergio, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner. 2024. “Failing Banks.”

Bank for International Settlements, Committee on the Global Financial System (BIS CGFS). 2017. “Designing Frameworks for Central Bank Liquidity Assistance: Addressing New Challenges”; Kelly, Steven, and Jonathan Rose. 2025. “Rushing to Judgment and the Banking Crisis of 2023.”

Indeed, Bagehot did not believe in bailing out insolvent firms—he had no argument with the Bank of England’s refusal to lend to the insolvent Overend, Gurney & Company, for example. He fully supported the Bank of England’s broad-based extensions of credit to many market participants to stem the contagion following Overend Gurney’s failure, however. See Bagehot, Walter. 1873. “Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market.”

See, for example, Bernanke, Ben S. 2015. “Fed Emergency Lending.”; Jones, Brad. 2023. “Bagehot and the Lender of Last Resort – 150 Years On.”; Madigan, Brian F. 2009. “Bagehot’s Dictum in Practice: Formulating and Implementing Policies to Combat the Financial Crisis.”; Praet, Peter. 2016. “The ECB and Its Role as Lender of Last Resort during the Crisis.”; Tucker, Paul. 2014. “The Lender of Last Resort and Modern Central Banking: Principles and Reconstruction.” For a much earlier example, see Anna Schwartz’s 1992 paper, which refers to the “ancient injunction to central banks to lend only to illiquid banks, not to insolvent ones.”

As Dobler, et al. (2016) notes, “A viability assessment is ‘business model’-focused, undertaken to determine that the entity can reasonably be expected to have continued potential for generating sufficient cash flow to repay the” central bank. It adds, “A bank that has sufficient capital today but is expected to run losses for the foreseeable future would not be viable.”

BIS CGFS 2017.

Dobler, et al. 2016; Goodhart, C.A.E. 1999. “Myths about the Lender of Last Resort”; Kelly, Steven. 2024. “Central Bank Liquidity Assistance: Challenges of Franchise and Asset Values in Banking Crises.”

Geithner, Timothy F. 2019. “The Early Phases of the Financial Crisis: Reflections on the Lender of Last Resort”; Tucker, Paul. 2020. “Solvency as a Fundamental Constraint on LOLR Policy for Independent Central Banks: Principles, History, Law.”

See also Kelly and Rose 2025.

AHEL programs are sometimes, though infrequently, effected by non–central bank lenders.