This Policy Brief is based on the ECB Occasional Paper: Capital Markets Union: a deep dive. Five measures to foster a single market for capital, published in March 2025 as part of the ECB’s Occasional Paper Series, no. 369.

Abstract

Europe needs a single capital market to support economic growth and resilience. Our paper proposes to focus policy action on five areas: (i) increasing savings and retail investment via the creation of a new standard for a European savings and investment product; (ii) integrating the EU’s trading and post-trading infrastructure while leveraging on the potential benefits of digitalisation; (iii) improving the supervisory ecosystem to be in line with the goal of a single market; (iv) mobilising the securitisation market to finance EU priorities without compromising on financial stability; and (v) increasing opportunities for equity and venture capital financing. While these actions have the potential to be a catalyst to make the most of Europe’s capital markets and increase the EU as an attractive investment destination, a key challenge will be to continue addressing barriers stemming from the lack of harmonisation in insolvency, corporate and taxation regimes, designing a safe asset for Europe, completing the Banking Union, and promoting financial literacy and inclusion.

A single market for capital is needed now more than ever. The capital markets union (CMU) has been a goal for the EU for the past decade, but it has yet to meet its intended ambitions. Europe needs investment to fund its defence, digital and climate priorities, prompting renewed policy interest in CMU. A more integrated capital market is essential to allocate resources more efficiently, connect savers with investment opportunities, and provide businesses of all sizes with access to diverse funding sources. A stronger, safer and more integrated market can support innovation and productivity and better equip households and governments for the demographic changes ahead. Finally, a single market for capital can promote inclusiveness and convergence across national markets and economies in the EU. The changing global context offers an opportunity to make the EU an attractive destination for capital and increase Europe’s open strategic autonomy. When the European Commission unveiled its new Savings and Investment Union (SIU) strategy, the CMU and its components were a prime element.1

Chart 1. CMU objectives

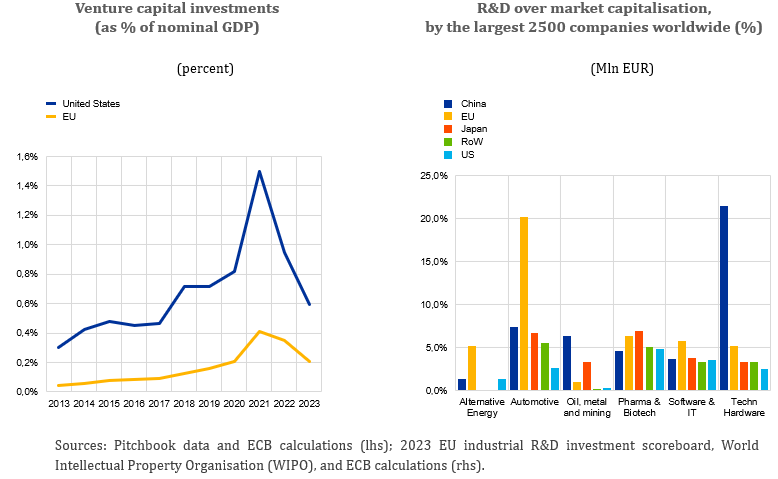

Financing innovation in Europe has become an urgent priority to boost productivity, competitiveness, and strategic autonomy in a rapidly evolving global economy. While bank lending continues to play a key role, high-growth companies require funding instruments better suited to their needs. These firms often operate without tangible collateral or predictable cash flows and depend on flexible, risk-bearing investment to scale and succeed. Capital markets, particularly equity and venture capital, are essential for start-ups and innovators to find the long-term funding they need. However, Europe still lags behind the US in the depth and accessibility of such market (see chart 2 lhs). This underdevelopment is one factor contributing to lower private R&D spending (see chart 2 rhs), fewer patents in high-tech sectors, and a widening productivity gap. Strengthening the single capital market is thus not only a complement to bank financing, but a necessity for Europe to build technological leadership and ensure future economic resilience.

Chart 2. VC financing of EU and US companies and R&D spending by private companies

Over the past decade, the Commission has put forward three CMU Action Plans and a wide range of legislative proposals and other initiatives. The EU has made progress toward a single capital market – such as improving SME listings, creating secondary markets for non-performing loans, and bolstering sustainable finance. Yet, the progress made has been limited, as the most ambitious reforms needed, such as aligning insolvency procedures and tax laws, were held back and other potentially impactful measures (such as a Pan-European Pension Product) were watered down in the process. Despite broad consensus on the benefits of integration, political will has not overcome existing barriers. The Commission now aims to tackle some of these structural issues in its new SIU strategy, notably with goals to boost retail investment, improve equity financing, integrate capital market infrastructure and unify supervision.

Momentum around the CMU project has grown amid a shift in its overarching narrative. Initially, the focus was on integrating and developing national capital markets to complement bank lending and enhance risk diversification, in order to strengthen the Economic and Monetary Union and follow on the successes of banking union. Now capital markets are in demand to meet the rising financing needs of the green and digital transitions, as Europe’s fiscal space has tightened following the COVID-19 pandemic. Mobilising private capital has become more urgent due to geopolitical uncertainties and the EU’s declining competitiveness compared to other major economies. And if policy makers seize the opportunity, it can also be the occasion to make the EU an attractive destination for capital.

A deep, integrated single capital market is now a strategic objective for Europe’s open strategic autonomy and resilience. This has led to a number of CMU proposals and recommendations, including in the landmark reports by Enrico Letta2 and Mario Draghi.3 Political engagement has also increased, as seen in the Eurogroup’s March 2024 statement4 on the future of CMU, in which finance ministers outlined their priorities. The CMU stands at a crossroads: these pledges of building a genuine single market for capital must be translated into concrete policy actions.

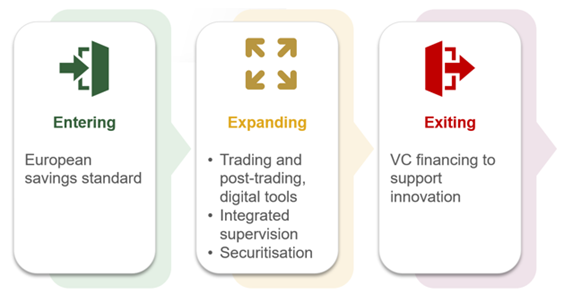

To catalyse the CMU project, a clear set of concrete goals that can feasibly be delivered over the current legislative term is needed.5 Five key actions stand out: (i) a new savings and investment standard, (ii) a more integrated trading and post-trading landscape bolstered by digitalisation, (iii) a more integrated EU supervision , (iv) a more active securitisation market that does not compromise on financial stability, and (v) more opportunities for equity financing, especially venture capital. These proposals aim to address bottlenecks at three stages: to facilitate access to capital markets (entering), expand capital markets across-borders (expanding) and channel capital towards innovative and competitive firms (exiting). Exiting in this context means getting the financing where it is needed, so innovators and technology firms can put it to work.

Chart 3. Five high-impact priorities for CMU

Better retail savings and investment products offer one of the most promising ways for capital markets to attract more savers. Such products could increase returns, reduce dependency on state-funded pensions, and make more financing available for companies. Successful national initiatives offer examples of how to make market-based products more attractive. Policymakers have a number of levers to consider: tailored tax incentives, flexible and easy-to-access product design, and the balance between EU standardisation of these product features vs national flexibility. Over the long term, increasing household’s participation in capital markets has the potential to boost individual wealth and broader economic growth. Product design should prioritise accessibility, transparency, portability and low fees, making it appealing to a diverse range of savers, with different levels of risk tolerance. It should not necessarily entail the creation of a new product, but build on the existing offer from financial services providers, without creating bureaucracy. Successful initiatives could take different forms, such as a European label applied on existing products that could be eligible for harmonised treatment across the Single Market; a newly designed European savings and investment product; or promoting and standardising national-level savings accounts that allow investors to invest in a range of products while benefiting from favourable tax treatment. While centralising certain features could ensure a level playing field and ease cross-border investment, maintaining flexibility would allow Member States to adapt any new instruments to local tax regimes and consumer preferences. This approach would foster broader adoption across the EU, while ensuring the savings product meets the unique needs of different markets.

The fragmented6 European trading and post-trading landscape should progressively evolve, leveraging on legal harmonisation and new technologies. The EU trading environment should aim towards a pan-European pool of liquidity, with support from fully comprehensive consolidated tapes and more inclusive European equity indices. To remove legal barriers, national corporate and securities laws should be harmonised over time. This process could start with targeted elements such as the processing of corporation actions (e.g. dividend payments, stock splits), or a 28th regime that sets up an EU standard firms can choose as an alternative to operating under national rules. In the longer term, market participants could reap the benefits of legal harmonisation to achieve a unified and consolidated trading and post-trading systems. Distributed ledger technology and other financial innovations can also help by enabling faster and safer transaction execution, provided these solutions are implemented in an interoperable manner following common standards.

The EU needs to move toward a more integrated supervisory ecosystem. Enhanced convergence, through more integrated EU supervision, would support a uniform implementation of rules, increase market confidence, and promote cross-border investments. While different models can be envisaged, the aim of coherent and ultimately integrated supervision should be maintained. Steps should already be taken to further harmonise capital market rulebooks, strengthen the role of the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs), and improve the consistency of EU-level regulation across market sectors. The ESAs should have adequate resources, governance and powers to improve and harmonise the functioning of the single market in capital, including direct supervision, for example with respect to market infrastructures that are systemically important for multiple Member States or even the whole EU.

Securitisation reforms can help banks use their balance sheets better, while regulatory and prudential standards must reflect underlying risks adequately. In the short term, fine-tuning some elements of the existing framework can support supply of and demand for securitisation. For example, streamlined due diligence and reporting requirements can reduce the administrative burden for both originators and investors without compromising on the progress achieved towards more transparency. To have a lasting impact, these initial actions should be combined with longer-term efforts toward standardisation and simplification to scale up and integrate the market. Maintaining prudent requirements will be key to guarantee the resilience and transparency of the market. While reducing capital requirements could increase incentives for banks to issue more securitisation products, it would not necessarily foster their placement in the markets. To the extent that banks keep some parts of these products on their own balance sheets, increased risk transfer benefits would not be achieved. The EU could also explore potential designs for securitisation platforms to reduce fragmentation. While the benefits of a platform would primarily be to enhance standardisation and therefore scaling up of the market, a targeted public guarantee could be considered. In this context, strategically focusing on loans for the green and digital transition could strengthen the link between specific proposed policy reforms for securitisation and increased lending for the broader goals of the CMU.

Venture capital and equity markets will need to scale up for EU firms to have access to adequate financing sources at all stages of their lifecycle. Developing venture capital should be an immediate priority to help the EU close its productivity gap. This would help channel funding to promising new firms and help address the current gap in late-stage financing that often leads European startups to seek funding outside the EU and subsequently list – or even relocate – elsewhere. Policy efforts can expand the investor base from public and private sources, ideally crowding in new participants. For example, the European Investment Fund (EIF) could be further mobilised towards venture capital to crowd-in private investors, ensure strategic investment in key sectors and provide stability in volatile times. Institutional investors that have the means to invest in venture capital whilst diversifying risk over a long-term horizon could also play a more active role in the market. Developing policies that incentivise these investors to diversify their portfolios and include more venture capital investments could unlock significant new funding for start-ups and scale-ups. Another avenue could be to lower entry barriers for retail investors to participate in equity and bond markets for these high-growth firms while also making progress in financial literacy, and ensuring adequate investor information and consumer protection. Over the medium term, making listing in Europe more attractive and efficient would enhance the depth and liquidity of listed equity in Europe, further enabling firms to start new businesses and develop into successful companies. Innovation hubs also are needed to connect research, funding and support for commercialising ideas throughout the Single Market.

As these priorities move forward, alternative pathways should be explored to advance integration, such as a 28th regime, enhanced cooperation, or a two-tier approach, given the political difficulty of full EU harmonisation in some areas. These flexible models may offer more feasible avenues to address long-standing barriers, enable cross-border provision of services, and improve regulatory consistency, particularly in areas like corporate, insolvency and tax law. It is important to understand the differences among the various models. A 28th regime can provide an optional, EU-level framework that firms may adopt in place of their national law in a given area. A ‘coalition of the willing’ (either as enhanced cooperation, envisaged in the EU Treaties, or in less formal arrangements such as the proposed ‘European competitiveness lab’) allows a critical mass of participating Member States to move ahead and adopt a common approach, paving the way for others to join. A two-tier approach enables targeted harmonisation for major cross-border players, ensuring proportionality and market impact. Although each pathway has limitations and requires careful policy calibration, they can offer practical means to deliver meaningful progress. Given the urgent need to advance the capital markets union project in Europe, these solutions merit serious consideration.

Implementing these five measures is critical and they need to be complemented by other important proposals that may take longer to realise, to complete the CMU agenda. Material progress over the coming legislative cycle can make a significant impact. In the longer term, policies will be needed to address even deeper structural issues, requiring strong political commitment and cultural shifts. These long-term needs include continued convergence in insolvency and taxation regimes, designing a safe asset for Europe, completing the banking union and promoting financial literacy and inclusion. Importantly, implementing the CMU agenda will improve the financing conditions to achieve European goals and it should go hand in hand with renewed efforts to remove other barriers within the Single Market, to support the necessary restructuring of European economies, and to promote European innovation.

See Communication on the savings and investments union: A strategy to foster citizens’ wealth and economic competitiveness in the EU published on 19 March 2025.

Enrico Letta, “Much More Than a Market-Speed, Security, Solidarity: Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens”, published in April 2024.

Mario Draghi, “The future of European competitiveness”, published in September 2024.

Statement of the Eurogroup in inclusive format on the future of Capital Markets Union, 11 March 2024.

See Lagarde (2024), “Follow the money: channelling savings into investment and innovation in Europe”, Speech at the 34th European Banking Congress “Out of the Comfort Zone: Europe and the New World Order”, November, Frankfurt am Main.

As of March 2023, there were 295 trading venues in the EU – not counting systematic internalisers – as well as 14 CCPs and 32 CSDs.