The overall EU climate agenda, along with the manifestations of the climate emergency, which have become markedly more visible in the past few years, have prompted an increase in the number of proposals for EU-level solutions to mitigate the climate emergency through public investment. In this policy brief, we look into the potential for an EU Climate and Energy Security Fund, focusing on its legal and institutional feasibility. Our findings suggest that such an EU-level tool would be effective, efficient, and legally feasible, addressing the limited returns on individual Member State action and ensuring European coordination. We highlight that Next Generation EU (NGEU) offers a precedent for financing a range of EU programmes and supporting reforms and investment by Member States in priority areas. Drawing on this precedent, we explore the legal requirements of a Climate and Energy Security Fund and the implications for its design. Lastly, we address the importance of democratic legitimacy and accountability for such an EU instrument.

There are compelling environmental, economic and legal arguments for the European Union (EU) and its Member States to increase their action to address the climate emergency through additional investment.

First, in addition to its worldwide consequences for humanity, the climate emergency will have a significant economic impact in the EU. It will damage capital stock and affect production and the welfare of households (Feyen et al., 2020), along with posing potential risks to fiscal sustainability in several Member States (Gagliardi et al., 2022). The intensity of this economic impact will be directly linked to the level of global warming in +1.5°C, +2°C and +3°C scenarios, and thereby to the level of ambition of climate action now being taken.

Second, the EU and its Member States are subject to a legal obligation under the Paris Agreement to mitigate the climate emergency by reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This binding commitment under international law has been incorporated in the EU legal framework by the European Climate Law. Moreover, national courts in Member States are increasingly requiring governments to take effective climate action to protect citizens’ fundamental rights, in particular the right to life and the right to private and family life (e.g. Setzer et al., 2022). National courts have held that the obligation to take suitable measures to protect fundamental rights applies to environmental hazards – specifically the climate crisis – even if the hazards only materialise over the long term.

Thus, the climate emergency calls for immediate action in line with the EU’s objectives under Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and with the principle of solidarity under the Treaties. This reflects the shared responsibility of the EU and Member States to comply with obligations under international law, and the interdependence of Member States in mitigating the impacts of the climate and energy security crises.

In addition to the climate emergency, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has increased concerns over energy security, strengthening the desire to frontload improvements in energy efficiency and increase domestic clean energy supply. In December 2022, the European Council reiterated the importance of stepping up investment in innovation, infrastructure, renewable energy and energy efficiency projects, in order to phase out the EU’s dependency on Russian fossil fuels, accelerate the green transition and ensure security of supply.

Against this background, our recent paper on “The legal and institutional feasibility of an EU Climate and Energy Security Fund” (Abraham, O’Connell and Arruga Oleaga, 2023) looks at how the EU can best fulfil its legal obligations to contribute to the global effort to mitigate the climate emergency, while also increasing the EU’s energy security. We first consider the estimated investment needs for climate mitigation and ways to address them. We then look at the specific option of an EU-wide tool and the policy discussions around it. Finally, we look at the legal considerations for such an EU tool, the EU Climate and Energy Security Fund, on both the revenue and the expenditure side, and their influence on the design options of the Fund, along with addressing the importance of democratic legitimacy and accountability for such an EU instrument.

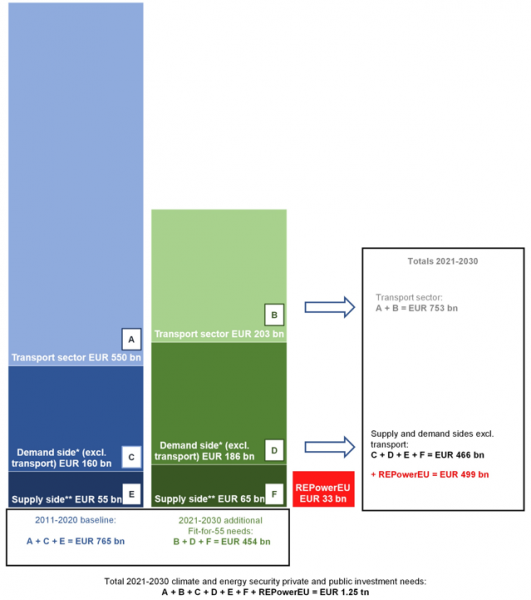

The European Commission estimates that in each year of the 2021-2030 decade, the EU needs €454 billion (in 2022 prices, see Figure 1) of additional investment to fulfil its 2030 climate commitments. A substantial share of this investment is expected to come from the private sector, with public policies such as carbon pricing having a key steering role to play to address market failures (Schnabel, 2020).

Nevertheless, significant additional public investment will be needed to help to foster breakthrough innovations and provide the EU-wide and national infrastructures that will make the transition possible for all actors. Based on the share of public green investment in Member States’ National Energy and Climate Plans and taking into account the 2030 climate targets, ECB staff research suggests that between 1% and 1.8% of EU GDP could be required for annual additional green public expenditure in the period 2021-2030 (Delgado-Téllez et al., 2022).

Overview of annual climate and energy security-related investment needs in the EU

Figure 1: Public and private average annual investment needs, 2021-2030, EUR billion in 2022 prices

Source: L. Abraham and C. Grynberg, based on Commission estimates. Notes: Fit-for-55 needs are based on the Commission’s MIX 55 scenario, which assumes carbon price signal extension to road transport and buildings and intensification of energy and transport policies for the EU to achieve 55% emissions cut by 2030. REPowerEU needs look at investments required to build an energy system that is independent from Russia as a fossil fuel producer. Additional green investment needs for wider environmental objectives (€150 billion per year at 2022 prices) are not shown in this figure. *Demand side excl. transport covers improvements to reduce energy consumption and related CO2 emissions in industrial, residential and tertiary sectors. **Supply side covers energy production, including power grid, power plants, boilers and new fuels production and distribution.

Fiscal policy therefore remains central to tackling the climate emergency. The discussion on how best to accommodate these significant additional public investment needs is multidimensional, given that the fiscal space which EU Member States have varies, and is generally lower than their climate investment needs, and given that higher interest rates may have a negative impact on green investment when compared with fossil fuel investment, because of the concentration of capital it needs in the initial years (Egli et al., 2022; Schnabel 2023). There is also a need to take into account supply-side constraints following the COVID-19 and energy crises, which could limit the capacity to quickly scale up investments. Lastly, in the longer term, reducing demand for fossil fuels and increasing renewable energy generation could contribute to reducing inflationary pressures (Panetta, 2022b).

The role of fiscal policy in addressing investment needs, including on climate, has been a key consideration in recent discussions on the EU’s fiscal framework. The European Commission’s approach in its recent legislative proposals would see Member States committing to national medium-term fiscal-structural plans that could feature a longer fiscal adjustment path if they include a sufficient set of reforms and investments to respond to EU priorities, including the European Green Deal, and address country-specific recommendations. From a central banking perspective, the Eurosystem had, in its reply to the Communication from the European Commission on the economic governance review of 19 October 2021, stressed that fiscal policy should become more growth-friendly and that addressing the challenges of the green and digital transitions would require significant private and public investment. The Eurosystem reply also noted the potential of EU-wide action and the role of national investment, supported by additional sources of revenue or a reprioritisation of expenditure.

Prior to these proposals, one option considered was the possibility of a “green golden rule” that would exclude net green investment from the fiscal indicators used to measure compliance with fiscal rules. However, some limits and concerns were raised in respect of such an approach, including the risk of underinvestment, or difficulties finding the balance between tackling investment needs and risks to fiscal sustainability (Ferdinandusse et al.,2022; Panetta, 2022a). Such concerns lead to the need to consider the potential benefits of other options, in particular an EU-wide common investment tool.

In recent years, proposals to undertake a coherent, joint effort to mitigate the climate emergency and to meet the EU and Member States’ commitments under the Paris Agreement have been brought forward by a wide range of academic and institutional actors. An IMF staff proposal for reforming fiscal rules suggested putting in place an EU fiscal capacity which could include a “climate investment fund” (Arnold et al., 2022). Former MEP Luis Garicano called for a new climate facility, overseen by an independent fiscal agency, to provide €57 billion annually in public investment (Garicano, 2022). Heimberger and Lichtenberger (2023) point out that temporary spending from the Recovery and Resilience Facility and the reform of the fiscal rules may not facilitate a sufficient increase of public investment, therefore calling for a permanent EU climate and energy investment fund amounting to at least 1% of EU economic output.

The European Commission has already launched important initiatives aiming to support climate-related spending. For instance, in its February 2023 Communication on a Green Deal Industrial Plan, the Commission announced that it intends to propose a European Sovereignty Fund in the context of the review of the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) before summer 2023, to support investment in critical and emerging technologies relevant to the green and digital transitions. Moreover, a Social Climate Fund addressing energy and transport poverty and supporting investments in energy efficiency and decarbonisation is expected to start operating in 2026. An EU Climate and Energy Security Fund could complement or even encompass such instruments.

The EU Climate and Energy Security Fund proposed in our paper would improve coordination of national initiatives, while supporting cross-border and pan-European projects involving European public goods. Indeed, climate protection and energy security have been identified as quintessential examples of European public goods, with policies in these areas generating significant cross-border spillover effects and EU-level action bringing potential economies of scale (Thöne and Kreuter, 2021; Calliess, 2021; Buti and Papaconstantinou, 2022). The Fund could also help address the issue of limited returns on Member States’ individual actions to tackle the climate emergency and the associated risk of free riding. Moreover, it can ensure that the required investment occurs where needed, despite national fiscal constraints. In other words, the heterogeneity of climate public investment needs across Member States, together with the heterogeneity of Member States’ climate investment capacity, could be addressed by a Fund that ensures investment takes place where it is most productive in helping meet the EU’s climate targets.

Such an EU Fund providing €500 billion by 2030 would be an effective and efficient option for addressing these climate and energy-related public investment needs. Based on the lower end of estimates from ECB staff research and assuming the Fund starts operating in 2024, it could cover around 50% of estimated additional green public investment needs by 2030.

While the Fund would primarily focus on mitigating the climate emergency and lowering physical risks over the long term, it could also finance targeted climate adaptation projects, so as to mitigate physical risks over the short- to medium term. Moreover, the Fund has the potential to enhance the credibility and effectiveness of the EU’s climate strategy, which may help limit transition risks.

To achieve the Fund’s goals, we propose that two complementary approaches should be combined. First, the Fund could finance projects directly managed by the Commission or by EU bodies, which could include some existing EU budget programmes in the climate and energy fields. Second, the Fund could finance investments submitted by Member States, based on clear criteria and guidance set at EU level and drawing lessons from NGEU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF).

Such funding should ideally take the form of grants, so that the limited fiscal space some Member States have does not hamper effective and coherent action across the EU. The guidance and criteria for allocating these two types of funding should incentivise cross-border projects with high European added value. For instance, European financing, along with an enhanced and faster assessment and approval procedure, could make Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEIs) in clean tech more attractive. While beyond the scope of this paper, the extent to which investment could generate additional revenue for new EU own resources could also be explored.

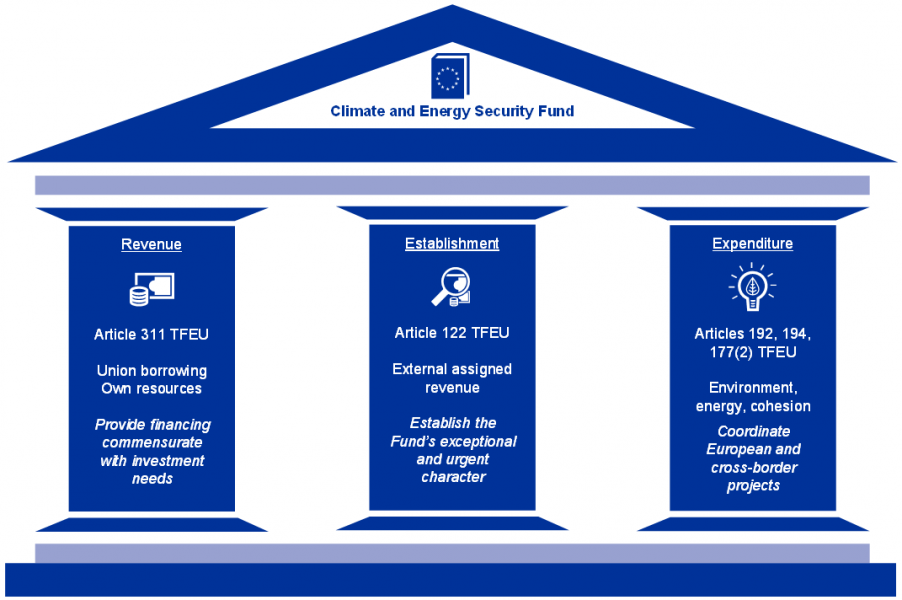

Our paper outlines that the legal design of this Climate and Energy Security Fund could be built on three pillars, drawing on the experience of designing and implementing the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme. Despite its relative novelty, the legal construction for NGEU has proven robust (see e.g., the assessment of the Council Legal Service, 2020). By contrast to the flight to intergovernmental solutions in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, existing legal bases under the Treaties were given a fresh interpretation in the light of the unique circumstances faced by the EU (de Witte, 2021), which have proven “sufficiently solid to erect the architecture of NGEU” (Fabbrini, 2022).

First, the revenue pillar of the Fund would enable EU borrowing through EU bond issuances in the capital markets for the purpose of providing grants or loans to support investment under the Fund. This would require an amendment of the Own Resources Decision in accordance with Article 311 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The possibility of introducing new EU own resources could also be explored. Second, the Fund could be established and accommodated within the EU’s financial framework by means of a regulation which would attribute the nature of “external assigned revenue” to the EU borrowing and/or new own resources flowing into the Fund. This would require a regulation to be adopted in accordance with Article 122 TFEU, often referred to as the EU’s “solidarity clause”. Third, one or more spending programmes could be established, setting out detailed rules on the conditions for using the Fund, including investment selection and disbursement conditions. A combination of legal bases under the EU’s competences in the fields of environment (Article 192 TFEU), energy (Article 194 TFEU) and cohesion policy (Articles 175(3) and 177(2) TFEU) could be used to adopt a package of legal acts establishing a variety of spending elements, including such programmes. Under the package, funding could also be channelled into suitable EU budget programmes already existing in the fields of climate and energy.

Establishing a Fund in this manner will face the same legal restrictions that have applied to NGEU. Compliance with these restrictions can be demonstrated by the fact that the Fund would be an exceptional, one-off and temporary measure, being one necessary step in an array of measures to tackle the climate emergency. The existential threat that the climate emergency poses to large parts of the world’s population, including within the EU, is an even more potent and immediate challenge than the COVID-19 pandemic. There is scientific and legal consensus at global and EU level on the need for immediate action within the current decade. In the EU, this consensus is manifested in the European Climate Law and an array of secondary legislation, which provides a solid basis and solid arguments for addressing the legal requirements for setting up a Climate and Energy Security Fund. Moreover, as a temporary measure, the Fund would provide an essential bridge towards comprehensive EU action over the long term, which could be fully designed within the MFF.

Figure 2: Legal construction of a Climate and Energy Security Fund

Source: Authors.

Finally, it will also be essential to safeguard the democratic legitimacy and accountability of such a Fund. Thus, it should be designed to include specific procedures to appropriately ensure the involvement of the European Parliament, particularly in view of the potential social impact of climate crisis mitigation policies and the significant impact of their success or failure on future generations.

It is still possible to mitigate the effects of the climate crisis, and there are compelling economic and legal arguments for the EU and its Member States to take immediate and meaningful action through public investment. Our findings suggest that an EU-level tool, in the form of an EU Climate and Energy Security Fund providing €500 billion by 2030 would be effective, efficient, and legally feasible, addressing the limited returns on individual Member State action and ensuring European coordination. The Fund would facilitate the scaling up of green investment geared towards the climate change mitigation, in line with European priorities, and would support price stability in the long term because it would help phase out fossil fuels and mitigate the effects of the climate crisis. The legal design we consider in our paper would allow for the establishment of the Fund in the short term in order to take immediate action commensurate with the climate emergency. Its design could allow for a phasing-in of the Fund which can be well-articulated with the implementation of NGEU. Such a Fund would be complementary to and compatible with other existing and forthcoming EU initiatives, include REPowerEU, the Social Climate Fund and the expected proposal for a European Sovereignty Fund ensuring that the European industry can take a leading role in the green transition.

Abraham, L., O’Connell, M., Arruga Oleaga, I. (2023), The legal and institutional feasibility of an EU Climate and Energy Security Fund, ECB Occasional Paper Series, No 313.

Arnold, N., Balakrishnan, R., Barkbu, B., Davoodi, H., Lagerborg, A., Lam, W., Medas, P., Otten, J., Rabier, L., Roehler, C., Shahmoradi, A., Spector, M., Weber, S. and Zettelmeyer, J. (2022), “The EU Fiscal Framework: Strengthening the Fiscal Rules and Institutions”, IMF Departmental Paper, 5 September.

Buti, M. and Papaconstantinou, G. (2022), European public goods: How we can supply more, VoxEU Column, 31 January.

Calliess, C. (2021), Public goods in the debate on the distribution of competences in the EU, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Cologne.

Council Legal Services (2020), Opinion of the Legal Services on the proposals on Next Generation EU, Brussels.

Delgado-Téllez, M, Ferdinandusse, M. and Nerlich, C. (2022), “Fiscal policies to mitigate climate change in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB.

De Witte, B. (2021), “The innovative European response to COVID-19: decline of differentiated integration and reinvention of cohesion policy”, ECB Legal Conference 2021, Continuity and change – how the challenges of today prepare the ground for tomorrow, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, pp. 394-402.

Egli, F et al. (2022), “Financing the energy transition: four insights and avenues for future research”, Environmental Research Letters, Vol. 17, No 5, 10 May.

Fabbrini, F. (2022), “Next Generation EU: Legal Structure and Constitutional Consequences”, Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, Vol. 23, pp. 1-22.

Ferdinandusse, M., Nerlich, C. and Osterloh, S. (2022), “Can green golden rules help to close the green investment gap?”, Box 3 in Delgado-Téllez, M., Ferdinandusse, M. and Nerlich, C. (2022), “Fiscal policies to mitigate climate change in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB.

Feyen, L., Ciscar, J.C., Gosling, S., Ibarreta, D. and Soria, A. (2020), Climate change impacts and adaptation in Europe, JRC PESETA IV final report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Gagliardi, N., Arevalo, P. and Pamies, S. (2022), “The Fiscal Impact of Extreme Weather and Climate Events: Evidence for EU Countries”, Discussion Paper, No 168, European Commission, Brussels.

Garicano, L. (2022), Combining environmental and fiscal sustainability: A new climate facility, an expenditure rule, and an independent fiscal agency, VoxEU Column, 14 January.

Heimberger, P., Lichtenberger, A. (2023), “RRF 2.0:A Permanent EU Investment Fund in the Context of the Energy Crisis, Climate Change and EU Fiscal Rules”, Policy Notes and Reports, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, January

Panetta, F. (2022a), Europe’s shared destiny, economics and the law, Lectio Magistralis on the occasion of the conferral of an honorary degree in Law by the University of Cassino and Southern Lazio, 6 April.

Panetta, F. (2022b), Greener and cheaper: could the transition away from fossil fuels generate a divine coincidence?, speech at the Italian Banking Association, Rome, 16 November.

Schnabel, I. (2020), When markets fail – the need for collective action in tackling climate change, speech at the European Sustainable Finance Summit, Frankfurt am Main, 28 September.

Schnabel, I. (2023), Monetary policy tightening and the green transition, speech at the International Symposium on Central Bank Independence, Sveriges Riksbank, Stockholm, 10 February.

Setzer, J. and Higham, C., (2022), Global trends in climate litigation: 2022 snapshot, LSE Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and Environment, London.

Thöne, M. and Kreuter, H. (2021), Public Goods in a Federal Europe, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Cologne.