Changes in climate policies, new technologies and growing physical risks will prompt reassessments of the values of virtually every financial asset. Firms that align their business models to the transition to a net zero world will be rewarded handsomely. Those that fail to adapt will cease to exist. The longer that meaningful adjustment is delayed, the greater the disruption will be. The TCFD provides the necessary foundation for the financial sector”s role in the transition to net zero that our planet needs and our citizens demand. Although the private sector has made rapid progress on reporting and risk management, more is required. First we must work to increase the quantity and quality of disclosures by sharing best practice. Second, the TCFD disclosure recommendations should be refined to those that investors consider most decision-useful. Third, we must spread knowledge on how to measure and use information on strategic resilience to manage risks and realise opportunities. Fourth and finally, the TCFD should consider how asset owners could best disclose how well their portfolios are positioned for the transition to net zero.

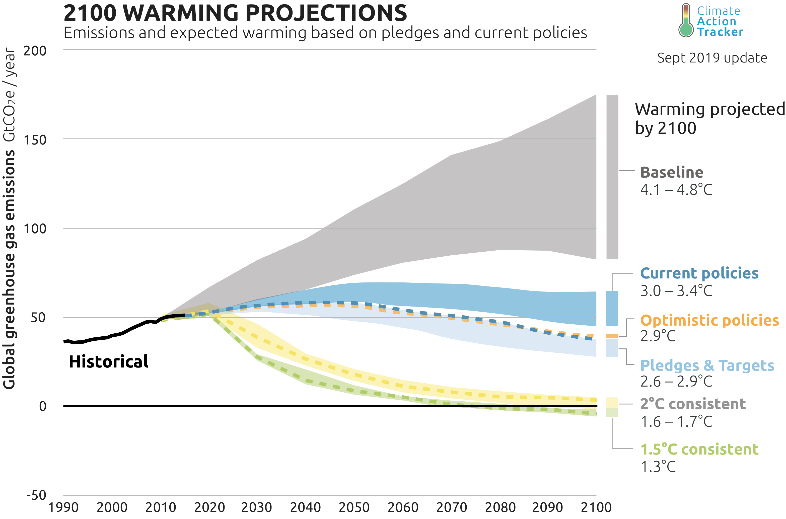

Over the past five years, global carbon emissions have risen by 20% and sea levels by over 3.3mm per year.1 Global temperatures are on course to increase by 3.4°C by 2100.2

Chart 1: Global warming projections to 2100 under different policy pathways

The physical impact of these changes will not be evenly distributed. With ferocious typhoons, record-breaking heatwaves and major landslides, Japan is already at the sharp end of a new pattern of devastating extreme weather events.

The transition to a low carbon economy will also bring its own risks and opportunities. Changes in climate policies, new technologies and growing physical risks will prompt reassessments of the values of virtually every financial asset. Firms that align their business models to the transition to a net zero world will be rewarded handsomely. Those that fail to adapt will cease to exist. The longer that meaningful adjustment is delayed, the greater the disruption will be.

Like virtually everything else in the response to climate change, the development of a more sustainable financial system is not moving fast enough for the world to reach net zero.

To bring climate risks and resilience into the heart of financial decision-making, climate disclosure must become comprehensive, climate risk management must be transformed, and investing for a two-degree world must go mainstream. Today, I want to focus on how the TCFD can help achieve these goals.

Only two years after the final TCFD recommendations were published, support has skyrocketed and conversations about climate-related financial risks have moved from the fringes to the forefront.

The demand for TCFD disclosure is now enormous. Current supporters control balance sheets totalling $120 trillion and include the world’s top banks, asset managers, pension funds, insurers, credit rating agencies, accounting firms and shareholder advisory services.3

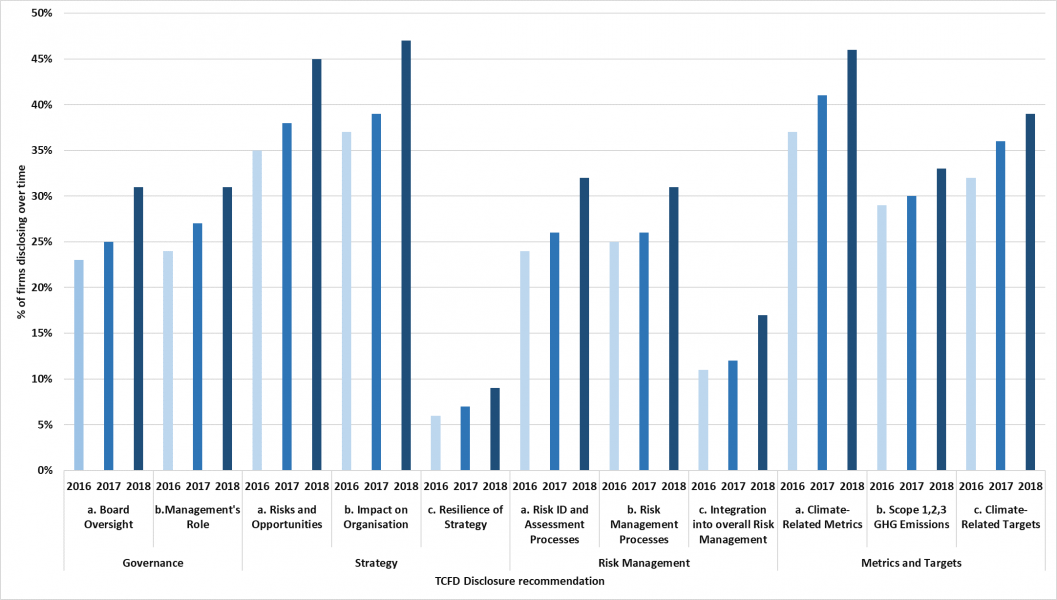

The supply of disclosure is responding, with four fifths of the top 1100 global companies now disclosing climate-related financial risks in line with some of the TCFD recommendations.4 On every recommended metric in TCFD, disclosures have been steadily increasing, rising from an average of 2.8 to 3.6 over the past three years. Three quarters of investors surveyed are now using TCFD disclosures when investing and the same percentage report a marked improvement in the quality of climate disclosures.5

Japanese TCFD supporters increased from 9 to 199 in just over a year and now have a market cap of almost $2 trillion. Japanese government support through the Implementation Study Group and the TCFD Consortium has catalysed action and created a blueprint for other countries in “how-to-TCFD”.

Chart 2: Changes in TCFD disclosures by recommendation 2016 – 2018

As the volume of disclosures has increased, so has their sophistication. Companies, financial firms and policymakers increasingly recognise that disclosures must go beyond the static to the strategic. Climate risks have a number of distinctive elements, which, in combination, require a strategic approach. These include their:

The nature of these risks means that the biggest challenge in climate risk management is in assessing the resilience of firms’ strategies to transition risks.

Markets need information to assess which companies can seize the opportunities in a low carbon economy and which are strategically resilient to the physical and transition risks associated with climate change.

The good news is that half the companies surveyed by the TCFD are using scenario analysis to assess the resilience of their strategies. Financial firms are at the forefront of these assessments.

The Bank’s supervisory body – the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) – surveyed banks in the UK last year and found that almost three quarters are starting to treat the risks from climate change like other financial risks – rather than viewing them simply as a corporate social responsibility issue.6

Banks have begun considering the most immediate physical risks to their business models – from the exposure of mortgage books to flood risk and the impact of extreme weather events on sovereign risk. And banks have started to assess exposures to transition risks in anticipation of climate action. This includes exposures to carbon-intensive sectors, consumer loans secured on diesel vehicles, and buy-to-let lending given new energy efficiency requirements.

To embed essential climate risk management skills recommended by the TCFD in financial decision-making, the Bank of England has set out its supervisory expectations for institutions in the world’s leading international financial centre with respect to:7

Recognising the need for industry to build capacity and develop best practices, the PRA has also established a Climate Financial Risk Forum, jointly with the FCA, to work with firms from across the financial system.

Although the private sector has made rapid progress on reporting and risk management, more is required. Over the next few years, companies, their banks, insurers and investors must:

Let me explain briefly what this means for the TCFD.

First, we must work to increase the quantity and quality of disclosures by sharing best practice.

Despite the increasing number of TCFD supporters, only a quarter of the companies surveyed disclosed information aligned with a fuller set – that is six or more – of the TCFD’s recommended disclosures.8

Three quarters of users of climate disclosures said that more information is needed on the financial impact of climate risks and the strategic resilience of firms.

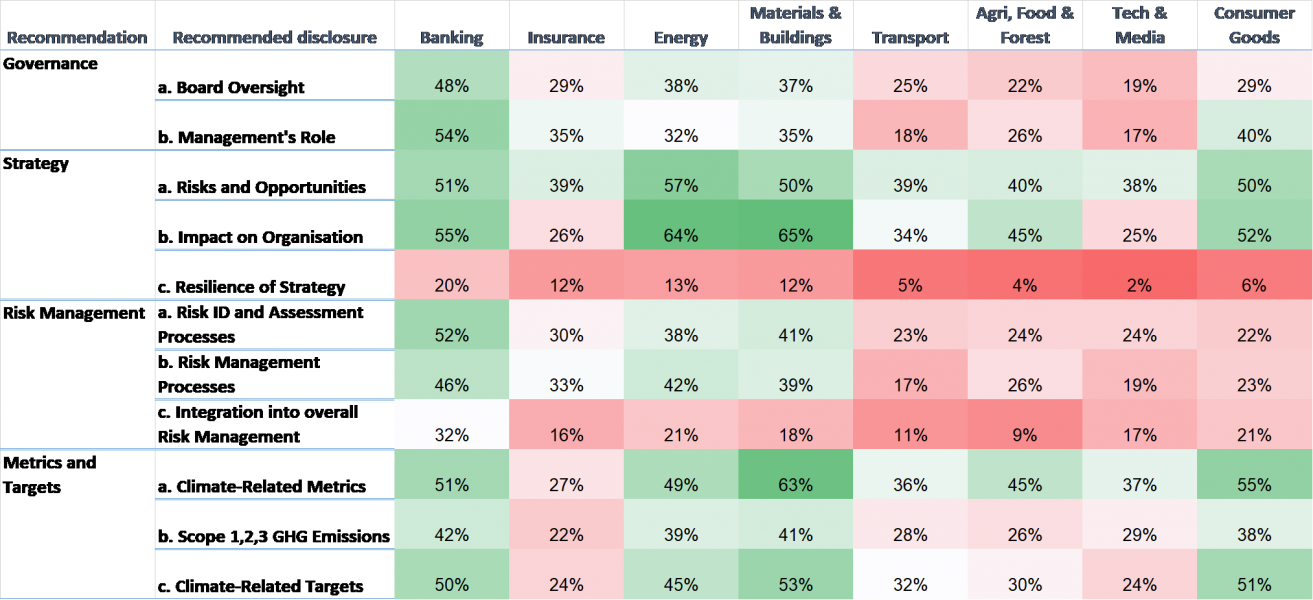

Progress in both quantity and quality is uneven across sectors. While in 2017 the non-financial sectors (energy, transport, building and agriculture) led the way, banking is now the most advanced sector in disclosing information.

Chart 3: Rates of disclosure against each of the TCFD recommendations by industry

Through multi-sector TCFD summits and more focused TCFD industry preparer forums, companies should continue to share knowledge on how, what and where they disclose information to give the market the information it needs.

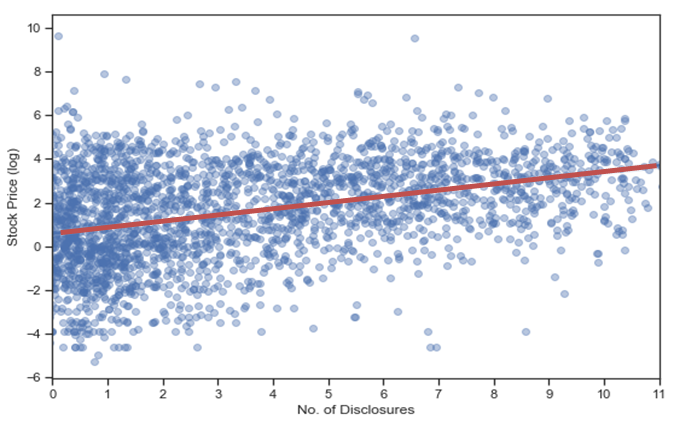

Better TCFD disclosure is an opportunity. Research by the Bank of England and PwC finds a positive correlation between companies’ stock price and the number of TCFD disclosures that firms make.9 This could be because investors reward companies that are leaders in managing climate-related risks or simply because TCFD adoption identifies companies that are more naturally disposed to longer-term strategic thinking and planning.

Chart 4: Relationship between stock price and number of TCFD disclosures made

And TCFD disclosure is increasingly a responsibility, as suggested by research from the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative that concludes that non-disclosure is a bigger liability risk than disclosure.10

That is just one reason why jurisdictions like the UK and EU have signalled their intentions to make TCFD disclosure mandatory.

Second, the TCFD disclosure recommendations should be refined to those that investors consider most decision-useful.

The TCFD needs to reach a definitive view of what counts as a high quality disclosure before they become mandatory. In my view, the next two reporting periods should balance the urgency of the task and the imperative of getting it right.

This is best delivered by the current process of disclosure by the users of capital, reaction by the suppliers of capital, and adjustment of these standards to ensure that the TCFD metrics are as comparable, efficient and as decision-useful as possible.

Supervisors of financial sector firms will also need to consider which metrics are most useful for different levels of assessment:

– Microprudential, to assess how individual firms are managing climate-related risks – for example the impact of a physical or transition risk on a loan book.

– Macroprudential, to consider how and whether individual exposures could scale up to systemic risk.

– Macroeconomic, to help understand how the financial system and economy interact in different climate transition scenarios.

Quantitative assessments could help guide these judgements. Research by the Bank and PwC found that some TCFD disclosures were positively correlated with the stock price of firms that have disclosed to date, with the disclosures about a firm’s targets, scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, risk management, resilience and impacts exhibiting the strongest correlations. Note that given the potential selection bias of companies with climate strategies tend to be early adopters of the TCFD, these correlations were positive.

Table 1: Strength of correlation between individual TCFD recommendations and stock price

This still nascent field will be important to understanding the utility of different climate disclosures. To this end, the Bank will continue its research.

Third, we must spread knowledge on how to measure and use information on strategic resilience to manage risks and realise opportunities.

Consistent with the Paris Accord’s objective to stabilise temperature increases to below two degrees, many governments are now committing to reaching net zero carbon by 2050.

In convening this Summit, Prime Minister Abe has rightly highlighted the enormous investments that will be necessary to deliver these objectives.

With an estimated US $90 trillion of infrastructure spending expected between 2015 and 2030, the right decisions now can make sure those investments are both financially rewarding and environmentally sustainable.

There has been a recent surge of environmentally focused investment funds. In Japan alone, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) assets quadrupled from 2016 to 2018 to reach $2 trillion.

As the transition gains traction, it is likely that both ESG and mainstream investors will increasingly focus on companies’ strategic resilience to climate change.11

95% of users found TCFD information on strategy useful, but three quarters want more information on the financial impacts.12 This year’s report to the Osaka G20 Summit found that, while firms were starting to consider strategic resilience, only about 50% systematically conducted scenario analysis and of those that did, three fifths did not disclose the information.13 Almost 80% considered the assessment of strategic resilience somewhat or very difficult, identifying a lack of relevant and granular data, the difficulty in determining scenarios to use, and the quantification of climate risks and opportunities as the biggest hurdles.14

This is not surprising – scenario analysis is a new and complex practice. And most of the off-the-shelf climate scenarios (such as the IEA and IPCC publications) are intended for policy or research, not business analysis. Improvements will be best achieved with collective force.

For some companies, scenario analysis is already part of their business planning and risk management. The TCFD report provides case studies – from Rio Tinto to Unilever to Citi – and finds common characteristics of good scenario analysis:

To develop leading practices, the TCFD has created a Knowledge Hub that provides guidance, research, tools, standards, frameworks and webinars.15

Looking ahead, the TCFD is currently considering how to:

The Bank of England is doing its part by assessing the strategic resilience of the world’s leading financial centre. The Bank will be the first regulator to stress test its financial system against different climate pathways, including the catastrophic business as usual scenario and the ideal – but still challenging – transition to net zero by 2050 consistent with the UK’s legislated objective.16

In response, banks will need to establish how their borrowers are managing current and future climate-related risks and opportunities. Those assessments will reveal:

The test will help develop and mainstream cutting-edge risk management techniques, and it will make the heart of the global financial system more responsive to changes in the climate and to government climate policies.

As with climate disclosure, such strategic assessments will need to go global if the world is going to stabilise temperatures below two degrees. That is one reason why the Bank is developing its stress testing approach in consultation with industry, the Credit Rating Agencies and the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) – a group of 42 central banks and supervisors (including the JFSA) that represent half of global emissions.

Fourth and finally, the TCFD should consider how asset owners could best disclose how well their portfolios are positioned for the transition to net zero.

For sustainable investment to go truly mainstream, it needs to do more than exclude incorrigibly brown industries and finance new, deep green technologies. Sustainable investing must catalyse and support all companies that are working to transition from brown to green.

Such “tilt” investment strategies, which overweight high ESG stocks, and “momentum” investment strategies, which focus on companies that have improved their ESG ratings, have outperformed global benchmarks for close to a decade.

More widespread adoption of such strategies is essential. At present, one of the biggest hurdles to doing so is the huge variation in the measurement of ESG.17

Common taxonomies to identify environmental outperformance, such as the EU’s Green Taxonomy and the Green Bond Standard can help but they tend to be binary (either dark green or all brown).

Mainstreaming sustainable investing will require a richer taxonomy – 50 shades of green.

One promising option highlighted by the UN’s Climate Financial Leaders is the development of transition indices composed of corporations in high-carbon sectors that have adopted low carbon strategies.

Consideration should also be given to the new assessments by leading asset owners of how well their portfolios are positioned for a two degree target.

Once again, Japan is leading the way. GPIF, the world’s largest pension fund, calculates that its portfolio is aligned to a 3.5 degree world. Allianz assesses that it is on 3.7 degree path and has committed to get to 1.5 degrees by 2050. AXA estimates that its assets are currently consistent with a 3.7 degree path, and it has developed an innovative climate Value-at-Risk model to measure the opportunities as well as risks from the climate-related exposures of its investments.18

With our citizens – led by the young – demanding climate action, it is becoming essential for asset owners to disclose the extent to which their clients’ money is being invested in line with their values.

The TCFD provides the necessary foundation for the financial sector’s role in the transition to net zero that our planet needs and our citizens demand. So whether the TCFD is used to manage the growing physical and transition risks from climate change or to finance the enormous opportunities to develop more resilient and sustainable economies, your work to develop the TCFD and spread its adoption is literally vital.

Climate.nasa.gov. Available at: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/sea-level/.

Source: Climate Action Tracker. Data available at: https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/.

Full list of current TCFD supporters is available at: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/tcfd-supporters/.

The TCFD’s June 2019 Status Report assessed, using artificial intelligence, 1100 companies reports over three years from 2016 to 2018 inclusive. Full report available at: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-TCFD-Status-Report-FINAL-053119.pdf.

TCFD Status Report (2019).

Prudential Regulation Authority report on the impact of climate change on the UK banking sector: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/report/transition-in-thinking-the-impact-of-climate-change-on-the-uk-banking-sector.pdf

TCFD Status Report (2019).

On average, each additional TCFD disclosure correlates with a 0.18% increase in stock price. While a positive correlation between financial metric and TCFD disclosure does not indicate that TCFD disclosure caused an increase in stock price, it raises questions for further analysis about the effect of climate-related disclosures.

“Laggard companies that fail to disclose climate risk in line with the TCFD recommendations may be less attractive to investors and struggle to secure loans or insurance. [F]ailure to disclose may suggest that a company has not considered climate risk, or that it has something to hide in relation to its exposure – either way, silence can send a warning signal to the market. Conversely, companies that embrace climate risk reporting will appear ahead of the curve and be well positioned to take full advantage of the commercial opportunities presented by the transition to a low carbon economy.” For full report, see: https://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/research/sustainable-finance/publications/CCLI-TCFD-Concerns-Misplaced-Report-Final-Briefing.pdf .

The Task Force encourages companies to describe the characteristics of their strategies that allow them to adapt to climate-related changes materially affecting their business while maintaining operations and profitability and safeguarding people, assets, and overall reputation. The TCFD report identifies that investors are likely to need information on the range of scenarios considered by a company; implications of each scenario for the business; strategic options considered; and the reasoning around the strategy adopted. Another factor that may warrant disclosure is the company’s ability – and flexibility – to adjust its strategy in response to emerging climate conditions, including alternative ways to use resources and the robustness and redundancy of business processes.

TCFD Status Report (2019) pg. 64.

TCFD Status Report (2019) pg. 63.

TCFD Status Report (2019) pg. 62.

This includes several industry associations and non-governmental organisations that have brought companies together to work through sector-specific approaches to climate change issues. For example, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) has convened or announced “preparer forums” for various sectors and industries: oil and gas; electric utilities; chemicals; construction; automobiles; and food, agriculture, and forest products. The United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative worked with 16 large global banks to pilot the TCFD recommendations and develop a scenario-based approach for assessing the potential impact of climate change on the banks’ lending portfolios.

The Bank of England set out in its July 2019 FSR its intention to test the UK financial system’s resilience to the physical and transition risks of climate change. It will gather views on the design of the exercise and, as a first step, will publish a discussion paper in autumn 2019. More information available at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financial-stability-report/2019/july-2019.pdf.

With the growth of different ESG measurement approaches, scores have been shown to vary greatly between providers. Barclays found positive but low correlations across all three ESG dimensions (14% for governance and 13% for environment) when comparing MSCI and Sustainalytics. Similarly, State Street Global Advisors found a correlation of 0.53 for constituents of the MSCI World Index.

See Axa 2019 Climate Report, available at: https://www-axa-com.cdn.axa-contento-118412.eu/www-axa-com%2F308285a0-f209-4b04-9a3e-41d8df848445_axa2019_ra_en_climate_report_19_07_2019_pdf_mel.pdf .