The international position of the euro is stagnating. Its share as a reserve currency is more or less the same as when EMU started in 1999. The use of the euro in cross-border trade outside the eurozone may come under pressure as China will soon launch its digital version of the renminbi, the DCEP. This currency will also be used in cross-border trade, by passing other systems and central banks. As strategic autonomy also requires monetary autonomy, Europe needs an independent cross-border payment infrastructure. A well-developed CBDC, which can be used in cross-border transaction, may be an effective answer to this challenge. Given the time pressure, the ECB may therefore consider introducing a wholesale version of the digital euro as soon as possible.

Worldwide, central banks are preparing to introduce digital central bank money (Central Bank Digital Currency or CBDC). This concerns a new digital variant as a supplement to the existing money. The European Central Bank (ECB) is now also working on a digital euro. It differs from the current book money (checking deposits, bank accounts) in that the digital euro is a liability of the central bank, just like the banknotes it issues. Book money, the money held in a bank account, is the liability of a retail bank and therefore appears on the balance sheet of the banking system. CBDC is sometimes described as a digital version of a banknote, but that representation is too simple. CBDC is more complex, and it will not have the characteristics of a banknote in all respects. However, in due course the digital euro will have a value of one euro, just like the cash and book money variety (ECB, 2021b).

So far, CBDC is mainly discussed in the context of the existing financial system and the impact it may have on payments and the position of banks and central banks. Therefore, the emphasis is on the so-called retail version of CBDC. As a result, the potential geopolitical impact of a digital euro that can be used across borders has received significantly less attention so far. The consequence of this is that the impact of the presence or absence of a digital euro on the international position of the euro so far has received relatively little attention as well, with BIS, (2021), ECB (2021), Bindseil et al. (2021) and Panetta (2021) being important exceptions.

The European Union (EU) has indicated that it aims to strive for what is known as strategic autonomy. This broad term suggests that it is primarily about a high degree of economic, political and military independence. A well-developed, globally used currency can also contribute to the political independence of the EU. The US’s financial powers that reach well beyond its shores due to the reserve currency status of the dollar is an example of this. However, this requires that this currency also has its own independent international payment infrastructure. In the absence of such an infrastructure, the political influence of a country is very limited. So far, the euro does not yet have that position. A well-developed digital euro is not only necessary to strengthen the international position of the euro, but can also ensure that its current position is not further eroded by the rise of the Chinese renminbi and its digital version, the DECP.

In this policy note, I will first briefly discuss the international position of the euro. Next, the international, financial infrastructure is discussed, with special attention to the dollar’s position in it and China’s efforts to strengthen the international role of the renminbi. This is followed by a discussion of the international dimension of CDBC and in particular its wholesale variant, with a focus of the potential positive contribution of the digital CBDC on the international position of the euro and Europe’s strategic autonomy.

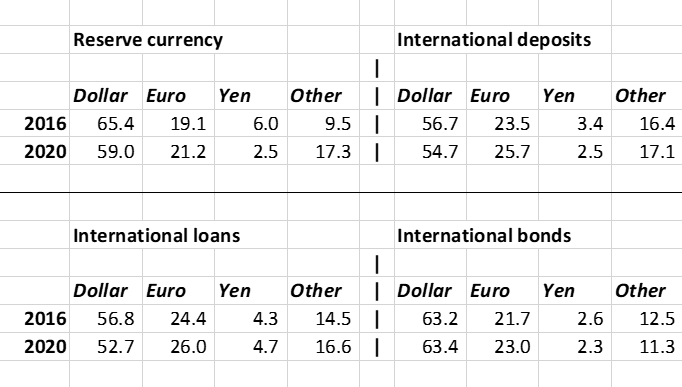

The euro has been a major currency from the first day of its existence. It is true that the US dollar is still by far the most important currency in the world, but the euro is a close second (Table 1). However, unlike the euro, the dollar is a truly global currency. This is reflected, for example, in the fact that many countries worldwide manage their exchange rates against the dollar. Also, many international transactions, such as those in commodities, are settled overwhelmingly in US dollars. In contrast, the international use of the euro as an invoicing currency is mainly limited to countries in the immediate European area and in Africa, where the CFA franc is tightly pegged to the euro (ECB, 2021; IMF, 2021, appendix).

Table 1. The international position of the euro in perspective (%)

Note: percentages are calculated from current exchange rates.

Source: ECB (2021).

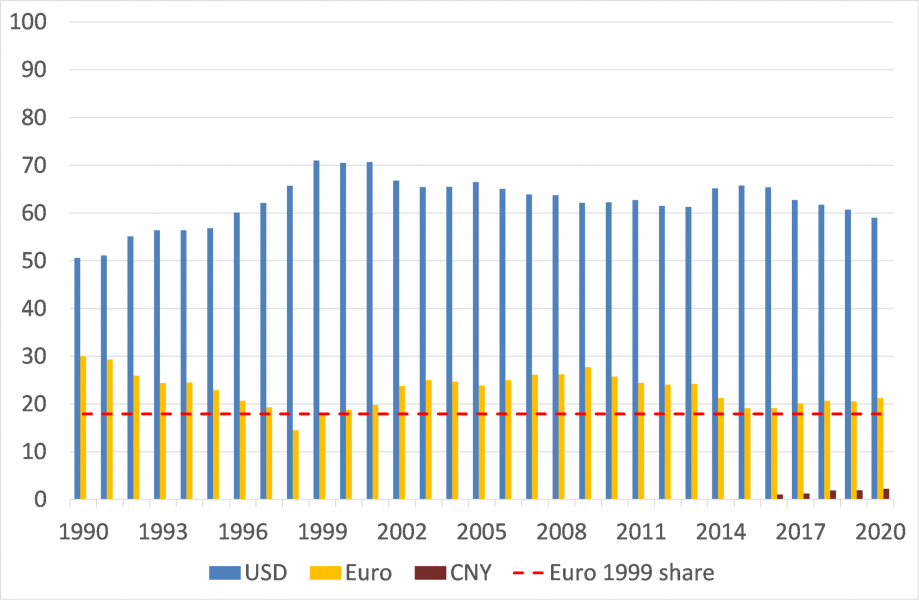

However, a closer look reveals that the international position of the euro is stagnating, as illustrated by the graph in Figure 1. This can be gauged, for example, from the share of the euro as a reserve currency. This is not substantially larger in 2021 than the combined share of its constituent currencies in 1999 (such as the German mark, the Dutch guilder, the French franc and the Italian lira), when the euro was introduced. This is despite the fact that the euro area has since grown from 11 to 19 countries. One reason for the stagnation of the euro’s development is the unfinished nature of the eurozone. The Banking Union is still incomplete, as is the Capital Market Union, which suffers from the absence of a well-developed market for EMU-wide common safe assets (securities issued by the EU with a guarantee from all member states). The first serious steps in this area were only taken in 2020 with the issuance of so-called ‘corona bonds’ by the European Commission. In times of turmoil, many investors still take into account the so-called ‘redenomination risk’, i.e. the risk that the eurozone ultimately will break up and the euro will cease to exist.

Figure 1. Share of euro, US dollar and renminbi in international reserves (%)

Note: Before 1999, the share of the euro was calculated on the basis of its constituent currencies.

Source: ECB.

The dominance of the US dollar gives the United States (US) considerable political power. This became apparent, for example, in 2018, when the US-government imposed sanctions against Iran because of its nuclear program. The EU did not agree, but could only watch as European business nevertheless conformed to US policy. It did this to avoid being hit by sanctions itself. This example illustrates that, when all is said and done, the strategic autonomy of the EMU is still a long way off. If the US imposes sanctions, European financial institutions will follow, irrespective whether or not the EU agrees with the US decision.

The US has good visibility into the behaviour of foreign companies because virtually all international payments are processed through SWIFT1. Now the EU and the US agree in many respects in international politics, as is also illustrated by the recent sanctions imposed on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine. But that is not necessarily always the case, as was illustrated by the Iran case. Furthermore, it would be extremely unfavourable for the EU if the Chinese renminbi took over the international role from the dollar.

Figure 2. The international asset position of the US (1976 – 2020)

(as a percentage of GDP)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, December 2021.

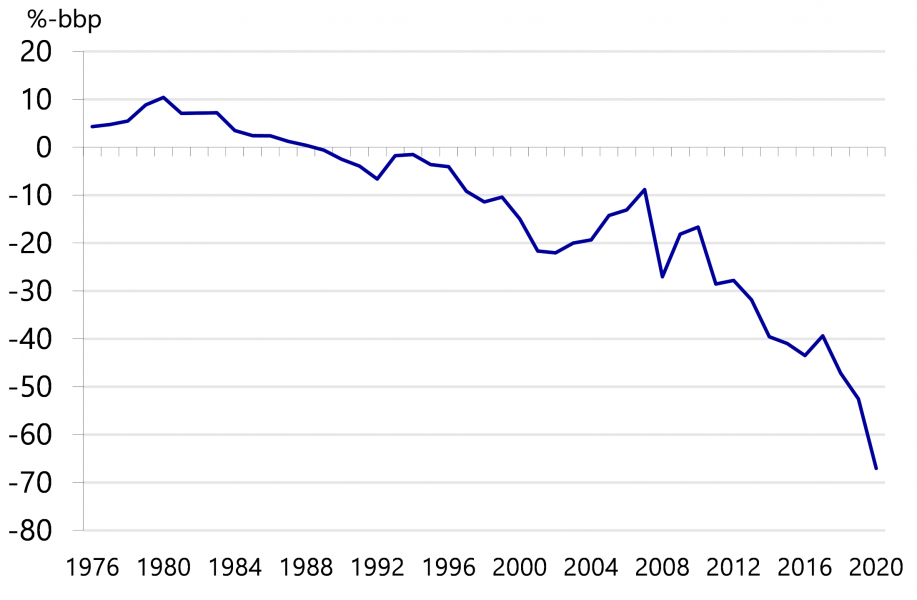

For the time being, however, the international position of the dollar is still unassailable. It is now slowly but surely eroding, partly because the US can now call itself the world’s largest debtor in absolute terms. Als a percentage of GDP, the US international asset position has now sharply deteriorated into deeply negative territory (see Figure 2). This illustrates a two-way relationship. As long as the US dollar is the central currency in international trade and investments, the world economy needs dollars, meaning that the US will be able to finance its foreign liabilities in its home currency. As a direct consequence, the US external position is not really problematic because the country will always be able to meet its international obligations (Boonstra, 2017). The moment that the importance of the dollar as international trade currency starts to decline, the chance increases that the US will have to finance (part of) its international obligations in foreign currency, which will speed up the dollar’s decline. The result could be a deep depreciation of the US currency against other major currencies.

However, today the dollar is nevertheless still by far the leading currency by a distance. This is mainly because no full-fledged alternative has emerged so far. However, China is working hard to develop the renminbi into a good alternative to the dollar (Overholt et al., 2016). At present, the Chinese currency is still a relative dwarf currency, even relative to the euro (see Figure 1). However, China is systematically working to strengthen its currency. In less than 40 years, the country has managed to move up from one lagging in almost every aspect, with huge poverty, to one of the largest and most economically powerful economies in the world. Today, China is a wealthy country, although its average GDP per capita is still low when compared to the US or the EU. China also has substantial net foreign claims. Militarily, it can now increasingly compete with the traditional superpowers, and this trend is accelerating. In short, there is every reason to also take the rise of the Chinese renminbi seriously. After all, in a number of ways China currently resembles the US of 75 years ago more than the US itself. Things can move fast, and the first steps on the renminbi’s long march have been taken.

Compared to traditional industrialized countries, China is far ahead in the introduction of a digital version of its currency, the renminbi. This too should be seen in geopolitical perspective, although it may not be apparent at first glance. After all, the stagnant development of the euro as an international currency, as outlined above, was not primarily caused by the absence of a digital euro, nor will its arrival simply fix it. This is also one of the conclusions of the ECB, when it discusses the potential effects of a digital euro for the international position on the European currency. It concludes that the international position of a currency is above all based on its fundamentals. The contribution of a digital euro is seen as of limited importance (ECB, 2021; Bindseil et al., 2021).

This line of reasoning seems to overlook, however, that the international position of the euro may come under pressure by the arrival of the DCEP, the digital version of the renminbi. China is expected to use it as a geopolitical instrument from the outset (Boonstra, 2020). The DCEP, which has been in the testing phase for quite some time, will not only be used in China itself, but it seems that it could soon be used to settle international transactions. This allows, for example, African exporters to get their goods exported to China paid for directly in DCEP. This in turn allows them to purchase products and services in China. It seems that such transactions can soon be carried out through the DCEP without the intervention of SWIFT (see below) or even their own central bank. In doing so, they will also be able to evade observation by the Americans.

For countries that want to avoid sanctions, or otherwise believe that the US does not need to be able to observe everything, the DCEP can offer a very welcome alternative. Think of major commodity exporters like Iran and Russia, that recently has been largely cut off from the international financial system, or some African countries. Arms transactions will probably also be able to be financially handled through this circuit, out of the sight of the US. It will also stimulate the international use of the (digital) renminbi. Moreover, once the use of a currency in international trade increases, this will more or less automatically translate in an increase in its market share in international deposits and international reserves (ECB, 2021). In particular, the way in which China, from the outset, wants to promote the use of the DCEP in Africa, can be seen as a targeted action to undermine the position of the euro. Indeed, it must be remembered that the CFA franc, which is an important aspect of the European orientation of much of Africa, is not popular in many countries in the CFA zone. This is because, in large parts of Africa, the CFA zone is mostly seen as a relic of colonial times. Once the renminbi rises in importance as a trade currency, it is also to be expected that its standing as a reserve currency will soon follow.

History shows that the international use of a currency is partly based on three pillars, namely the strength of the economy, political influence, supported by military power, and financial development.2

With this come two important observations. One is that markets are fairly inert, which is due to network effects. That is, market participants stick to existing practices for a long time. Once a currency is accepted as the dominant anchor currency, markets continue to treat it as such, even as the original foundations beneath it slowly erode. For example, England’s dominance under the gold standard had steadily eroded over time, but the pound officially retained its status as the leading currency until September 1931 when the United Kingdom left the gold standard. By then the country had been overtaken economically, and even surpassed by some other countries (such as the United States and initially Germany), had emerged impoverished from World War I, and was no longer militarily dominant. After World War II, it was abundantly clear that the United States was the absolute economic and military superpower, and the dollar took over the role of the British pound.3 Since then, however, American dominance in these areas has steadily declined. Today, the importance of the dollar in the global financial system is significantly greater than can be justified by its weight in the world economy. China is ‘the new kid in town’. The second observation is, that the transition from one anchor currency to another is not necessarily smooth. This applies not only to the transition from pound to dollar, but also to earlier periods when major currencies, such as the Dutch guilder in a more distant past, fell from their pedestals.

In a well-developed financial system, such as in many European countries, CBDC has little added value for domestic payments. This may change if the use of cash were to decline further and, in extremis, disappear (ECB, 2021). In countries with low financial inclusion, which means that many people have no access to banking services such as a payment, credit or savings facility, the situation is already substantially different. These are mostly emerging markets. But for all countries, CBDC can help to better facilitate cross-border payments. A well-designed CBDC can also help to protect a country’s monetary autonomy by preventing private so-called ‘stablecoins’ from growing so large that the central bank loses control over the money supply and financial stability.4 This plays into both retail and wholesale CBDC.

The international dimension of retail CBDC

By retail CBDC we mean a digital currency issued by the central bank and developed for domestic payments. It is in a one-to-one relationship with the existing cash and book money. Residents, mainly private individuals and small businesses, can hold a balance at the central bank. Central banks see CBDC as a complement to existing cash and non-cash money. It is currently not yet clear what the European CBDC, the digital euro, will look like exactly, and how large the CBDC circuit will be compared to existing money. For the ongoing discussions on retail CBDC we refer to the literature (ECB, 2021; BIS, 2020; Gnan, E. & D. Masciandro (eds.), 2018). For here, we will focus on the international aspects of CBDC.

Although retail CBDC is predominantly aimed at domestic residents, it will also have an international dimension. From the outset, non-residents will also want to use it. Think for example of tourists, who when visiting our country can now also pay with cash euros. Furthermore, there are temporary residents or non-residents with family in our country who would like to hold an account in digital euros. More importantly, central banks also seem to be working on linking national CBDC networks together. Then, for example, someone could quickly and cheaply transfer money from his euro-denominated CBDC account at the ECB to a CBDC account of a relation at a foreign bank and denominated, for example, in US dollars, Swedish crowns or British pounds. Such payments now go through the correspondent banking circuit of the banks or through specialized payment companies. Today, these transactions are relatively slow and expensive.5,6

If central banks can market a reliable, fast and cheap alternative to this, it is good news for citizens. CBDC may therefore be an opportunity to shorten the chain of correspondent banks, simplify mutual clearing and bring regulations more in line with each other. For the private banks and other financial parties operating here, of course, this means that a source of revenue dries up. The amounts can be substantial. When El Salvador decided in June 2021 to introduce Bitcoin as legal tender, alongside the dollar, the main reason was that it could save substantially on remittances from abroad. Salvadorans living in the US transfer large sums of money to their families every year using the process described above. By converting the money into Bitcoin, sending it via the blockchain to their families, who then convert it back into dollars, they expect to save about several hundreds of millions USD in costs annually. Incidentally, via a CBDC-based circuit, in this case a digital dollar to be issued by the Salvadoran central bank, between central banks this could be done just as well and quickly, but without the price risk between Bitcoin and dollar.

The international dimension of wholesale CBDC

Wholesale CBDC is less tightly defined than retail CBDC. It is similar to the liquidity reserves, that banks currently hold with the central bank. These reserves are used for the interbank settlement of payment transactions. Liquidity reserves will therefore certainly be part of wholesale CBDC in the future, as will the balances held at the central bank by, for example, securities settlement firms. But wholesale CBDC is likely to include more than just liquidity reserves as we already know them today. It may also include, for example, CBDC balances held at the central bank by certain financial institutions, such as mutual funds, pension funds and insurers, and large industrial companies. In addition, wholesale CBDC is characterized by relatively high amounts and low transaction numbers, while retail CBDC will mainly involve a lot of transactions with relatively low amounts.

Most international payments between professional parties are settled through the so-called SWIFT system. The market position of SWIFT is strong, the company seems to have a de facto global monopoly in this area. The current discussion about whether or not to exclude Russia completely from SWIFT after its invasion of Ukraine underlines the importance of SWIFT. As we stand at the tie of writing, Russia is only partly cut off from SWIFT, which already is seen as a major and painful sanction. The Economist journal describes the ultimate sanction, the complete removal of a country from SWIFT, as a ‘weapon of mass disruption’ (Economist, 2020b). The problem is, however, that this sanction may become less effective over time and, ultimately, may even undermine the US financial dominance (Economist, 2020a, 2021).

Even before the recent crisis, there were already plenty of parties and countries who would like to make their international payments outside of SWIFT. The recent sanctions will have made these countries even more aware of their vulnerability that results from their dependence on SWIFT for international transactions.

Founded in 1973, SWIFT is an international cooperative under Belgian law. It settles transactions quickly and reliably and their systems are almost always available.7 In practice, however, as explained above, the US has a great deal of influence over it. They can monitor transactions in SWIFT and also have the power to exclude countries from SWIFT. Earlier, I mentioned the example that when the US imposed sanctions on Iran, many European companies felt compelled to comply, even though the EU did not join the US sanctions politically. If central banks manage to link their national CBDC systems, a scenario is conceivable where international payments can also be settled relatively easily outside SWIFT.

If Eurozone countries had a good alternative to SWIFT using CBDC, it would significantly increase the EU’s autonomy from the US. It would give European companies the opportunity to evade US sanctions and conform to the European political position if they wish. A downside is, of course, that countries with ’bad’ regimes are now also developing alternatives to SWIFT. This would also give them the opportunity to evade sanctions, in whole or in part. With the digital renminbi, the DCEP, China seems to be opening up the possibility for foreign parties to pay directly in DCEP. After Russia was hit by sanctions after the previous Ukraine crisis, in 2014, the country started to work on an alternative to SWIFT, called SPFS (Economist, 2021). Although this is still at a relatively primitive stage, several countries have already been approached to join this network, including Belarus, Kazakhstan, Turkey and Iran. Talks are also underway with China to integrate SPFS with the Chinese alternative to SWIFT, CBIBPS.8 It would allow these countries, should they be affected by international sanctions, to still trade between themselves each other, out of sight of the US. Once this system is fully developed, it will be possible to conduct international transactions outside the view of the US. Ultimately, it could also considerably undermine the current imposition of sanctions against Russia, a major oil-exporting country. Furthermore, sources report that some banks in Germany and Switzerland are already connected to SPFS.9

These developments also help explain why the DCEP is enjoying a favourable reception in Africa. Several countries affected by US sanctions are in Africa. A high degree of acceptance of the DCEP in Africa will certainly strengthen the international position of the renminbi, which may be at the direct expense of the euro.

The biggest and most tangible effects of the advent of a digital euro will be visible in the domestic payments market and the banks’ position in it. Yet, in various ways, the digital euro also affects the international position of the European single currency. First, it consolidates the central bank’s position by preventing private stablecoins from undermining the central bank’s monetary autonomy. Incidentally, this danger is especially prevalent in less-developed and financially less-stable countries. In well-developed markets with a strong economy, a high degree of financial stability and an effective supervisory structure, such as the EMU, US and other industrialized countries, this is less of an issue. Second, a well-designed digital euro is an important precondition for the fulfilment of the strategic autonomy that the EU claims to aspire to. Noting again that strategic autonomy is a much broader concept. It requires not only the formulation of a strategic policy agenda, but also defines the preconditions within which the EU can determine and effectuate its position independently in all respects. This also requires, for example, substantial investments in defence and related industries, among others. But if it is possible, via a network of central banks (by connecting national CBDC systems) parallel to SWIFT, to facilitate international payments quickly and cheaply, this also increases the political independence of the EU. The downside of this is that it also makes it easier for countries against which sanctions have been imposed to circumvent them. Thirdly, there is a more defensive consideration. Now that an economic and geopolitical superpower like China is introducing a digital version of its currency and directly allowing foreign trading partners to make payments directly to their Chinese partners, other major countries cannot be left behind. If, in due course, the digital euro is not at least as user-friendly as the DCEP, especially in cross-border transactions, it will undoubtedly damage the international position of the euro, and thus the autonomy of the EU. In the worst case, Europe may end up with a currency that it is not only completely overshadowed by the dollar, but also by the Chinese renminbi.

A final remark concerns the speed with which China is introducing the DCEP. This will probably be fully operational within the next year or so. This makes the work on the digital euro more urgent. At the same time, it is widely expected that it will takes several years before the digital euro will arrive. Therefore, the European Central Bank could consider splitting the project between a retail and a wholesale CBDC and make sure that the wholesale CBDC, which probably will be less complex than the retail version, is introduced as soon as possible.

Bank for International Settlements (2020), Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles and core features, Basel, October 9th.

Bank for International Settlements (2021), Central digital currencies for cross-border payments. Report to the G20, Basel, July 21th.

Bindseil, U., F. Panetta & I. Terol (2021), Central Bank Digital Currency: functional scope, pricing and controls, ECB Occasional Paper No 286, December.

Boonstra, W.W. (2017), The US external debt is no cause for concern, yet, VOX EU, August, 2018.

Boonstra, W.W. (2020), Chinese digital currency to have international implications, Special Report, Rabobank, December 10th.

Economist (2014), The pros and cons of a SWIFT response, November 22th.

Economist (2020a), America’s aggressive use of sanctions endangers the dollar’s reign, January 18th.

Economist (2020b), How America might wield its ultimate weapon of mass disruption, August 13th.

Economist (2021), The hidden costs of cutting Russia off from SWIFT, December 18th.

European Central Bank (2021a), The international role of the euro, Frankfurt, June.

Gnan, E. & D. Masciandro (eds., 2018), Do We Need Central Bank Digital Currency? Economics, Technology and Institutions, Findings from a conference organized by SUERF and BAFFI CAREFIN Centre, Bocconi University, Milan, June7th.

International Monetary Fund (2021), Annual Report, Washington

Overholt, W.H., G. Ma & C. Kwok Law (2016), Renminbi rising. A new global monetary system emerges, John Wiley, Chichester (UK).

Panetta, F. (2021), “Hic sunt leones” – open research questions on the international dimension of central bank digital currencies, Speech at the ECB-CEBRA conference, Frankfurt am Main, October 19th.

Roberts, R. (2016), When Britain went bust. The 1976 IMF crisis, OMFIF Press, London.

Note that SWIFT is a Belgium-based cooperative of several hundred international banks. The US has a lot of influence there, partly because in almost all cases either the dollar is used, a US bank is involved as a correspondent bank, or US software is used somewhere along the chain.

The two currencies that could develop into truly global money – notably the British pound during the gold standard and the US dollar since 1945, both of which were the currencies of the most politically influential country at the time – were carried by the largest and best-developed economy with the most advanced financial system (well-developed markets, strong, internationally-operating financial institutions, net claims on foreign countries) and were backed by a powerful military apparatus that could project power globally, for example through control of international sea and trade routes.

In spite of the dollar’s dominance, Sterling retained a position under Bretton Woods as an official semi-anchor currency. For example, the countries of the Commonwealth held the main part of their currency reserves in sterling balances with the Bank of England. During Britain’s IMF crisis of 1976, the UK needed a major dedicated loan from the IMF to support the exchange rate of Sterling, in order to prevent a deep depreciation of the currency. Such a depreciation would have resulted in major losses for these countries on their Sterling reserves (Roberts, 2016).

A stablecoin is a covered crypto currency, meaning that (in theory) its value is determined by high-quality financial assets, purchased with the traditional money deposited.

This inertia arises because several links (parties) are involved in the chain. The parties involved also make a profit when exchanging one currency for another. Furthermore, there are (large) differences in laws and regulations in different countries. For example, there are differences in the implementation of Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations. Furthermore, the settlement of interbank transactions does not take place in the same way everywhere. Moreover, the opening hours of the various currencies are different, and the message standards may also differ.

Incidentally, many companies are already less dependent on the relatively poorly developed correspondent banking systems because they already maintain checking accounts with foreign banks.

Note, that SWIFT does not conduct the financial transactions itself, as those are conducted by the central and other banks themselves. But it arranges the documentation.

CBIBPS stands for Cross-Border Inter-Bank Payments System. According to the Economist, CBIBPS is already conducting 50 million transactions per day, compared with 400 million transaction per day through SWIFT). It is rapidly developing into a serious competitor for SWIFT (Economist, 2021).

Western governments could, of course, try to prohibit Western banks from participating in SPFS and CBIBPS, although it is an open question whether this could be done watertight. This might complicate the development of these alternatives to SWIFT, but in all likelihood would not stop it.