This policy note puts the current taxation of immovable property in the euro area/EU into perspective with theoretical best practice considerations based on a literature review. In particular, it surveys the literature on immovable property taxation along two dimensions prevalent in the literature: i) according to the type of real estate over its life cycle and ii) according to the type of tax. The first strand of the literature agrees that immovable property taxation should be neutral to the extent possible to avoid overly distortionary behaviour vis-à-vis other assets/consumption goods. The second strand assesses one specific property tax with respect to efficiency, equity, fiscal federalism and political economy aspects. In line with its theoretical merits, most of this strand of the literature focuses on recurrent property taxation on residential property. A key message of both strands is that reaping the theoretical merits of immovable property taxation in practice is hindered by tax design and political economy issues. Hence, practical real estate taxation differs a lot from theoretical best practice considerations.

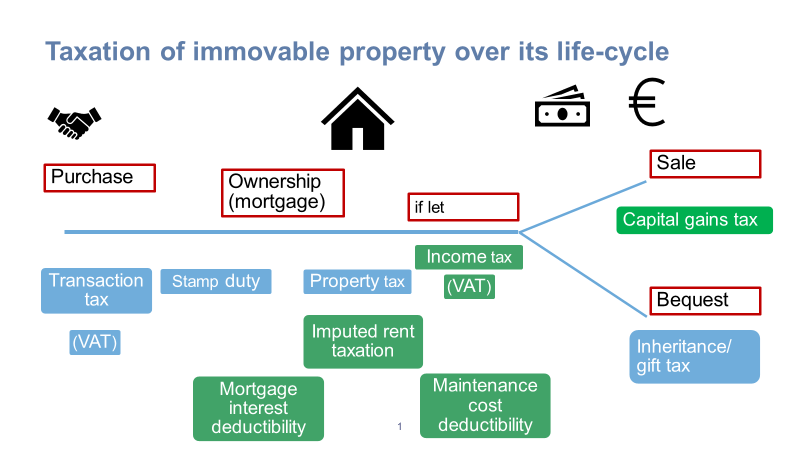

Before referring to the literature on real estate taxation, a natural starting point is to recall where in its life cycle immovable property is actually subject to which tax. Graph 1 gives an overview of the most common immovable property taxes applied in the EU over the object’s life cycle. It starts with taxes due at first purchase for an owner, ending with the object’s transfer to a new owner, when the object’s life cycle – and tax liabilities – starts again.

Graph 1:

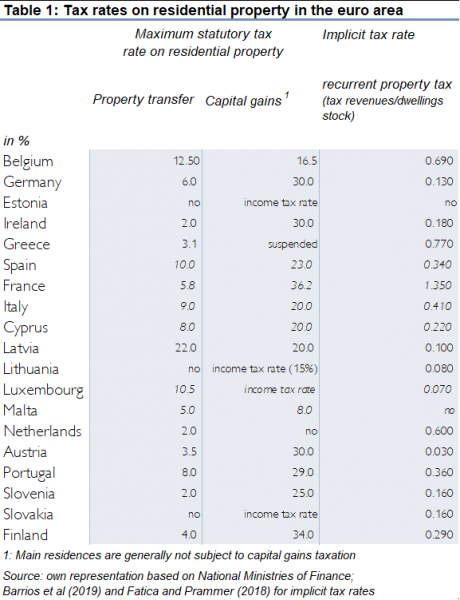

The purchase of immovable property is subject to a property transfer tax in almost all EU member states (exceptions are Estonia, Lithuania, Slovakia). This tax is usually based on a stock, namely the value of the property, typically measured by (some share of) the transaction price. Maximum statutory tax rates reach up to 12.5% of the transaction price in Belgium (see table 1), with various exemptions and deductions for first time buyers, permanent residences or small/inexpensive property. New buildings are subject to VAT based on the transaction price in most EU member states, which sometimes replace (low) property transfer taxes. In addition, all EU member states levy some kind of stamp duty linked to the legal recognition of the immovable property transfer and its registration.

The ownership of immovable property is subject to recurrent property taxes. The basic case of a recurrent tax on residential property is a flat rate which is levied on the cadastral value of the property by local authorities. Some, particularly new, member states levy area-based local property taxes (Brzeski et al., 2019). Only a few member states, namely Croatia2, Malta, Estonia and Italy3 do not levy recurrent property taxes. Despite their widespread use, the revenue from recurrent taxes on immovable property is rather low, amounting to only 1.5 % of GDP in the EU-28 on average in 2019 (EA-average: 1.3% of GDP). This is due to the use of the cadastral values as the tax base, which often fall short of up-to-date market values. Cadastral values in Germany and Austria are particularly outdated – stemming from the 1960s and 1970s, respectively.4 Hence, the implicit recurrent property tax rate is well below 0.5% (of the stock of real estate) in the euro area (see table 1), despite the considerably higher statutory tax rates. An alternative to recurrently taxing the stock of immovable property is a tax on imputed rents. In this case a tax is levied on the fictitious flow of rental income – usually by adding it to other income categories; it is, however, currently only applied for main dwellings by the Netherlands.5

If the owner rents out the property and earns actual rental income, the case for a tax on the actual flow of rental income is clear cut. This income is subject to some kind of income taxation in all EU member states. If a private purchase of the immovable property is financed by a mortgage, mortgage interest rates are at least partially deductible in about 2/3 of the EU member states (Johannesson-Linden and Gayer, 2012; Fatica and Prammer, 2018).6

The sale of the immovable property is generally subject to a capital gains tax, where the difference between the sale and the overall purchase price is taxed in almost all EU member states (see table 1). At the same time, those member states which tax the profits, allow for generous exemptions for the main residence. Usually, capital gains on the main residence are tax exempt subject to a minimum time of tenure (2-5 years) or provided that the capital gains are reinvested in the acquisition of a new main residence (e.g. Spain). If immovable property is transferred charge-free in the case of an inheritance or gift, the transfer is subject to inheritance/gift tax in about half of the EU member states7. Even if a country does not apply a general inheritance/gift tax, the cost-free transfer of immovable property might still be subject to taxation (e.g. Austria).

2. Immovable property taxation in theory

The ample literature on immovable property taxation can be grouped into two strands. The first covers the taxation of one type of real estate over its life cycle, such as owner-occupied housing. It highlights the distortions property taxation introduces into housing investment and consumption decisions compared to other assets/consumption goods. The second strand assesses the advantages and drawbacks of one particular tax on immovable property (at one point in time of the lifecycle), such as recurrent property taxation. The literature assesses the taxes with respect to induced distortions and their effectiveness and efficiency for economic growth, equity and fairness, fiscal federalism considerations and political economy obstacles.

Taxation of one type of real estate over its life cycle

Real estate property can be produced for rent in a market by a landlord, for investment and use as a business input by a firm or for investment and own use by an owner-occupier. These different purposes of real estate property would call – according to optimal tax theory – for different taxation. The matter is complicated by the fact that uses may change over time.

Owner-occupied housing serves a twofold function for its owners: First, housing usually presents the largest asset of a household; second, living in a home provides a flow of services consumed by the owner. If the first view prevails owner-occupied housing should be taxed as any other asset to achieve neutral taxation, while the second view would call for the taxation of owner-occupied housing like any other durable consumption good.

Tax neutrality of owner-occupied housing with respect to other assets would hence call for taxing the net return of owning a house, i.e. taxing the imputed rent (fictitious rental income) as well as capital gains from selling the property while allowing for the deduction of costs, such as depreciation and maintenance costs as well as interest payments in the case of debt-financed purchase. In practice, as stated above, the current treatment of housing taxation leaves imputed rents and capital gains for primary residences mostly untaxed while allowing for mortgage interest deductibility. Hence, the user cost of housing capital is reduced by almost 40 percent compared to the efficient level under neutral taxation in the euro area, which translates into an excess consumption of housing services equivalent to about 30 percent of financial asset holdings in household portfolios (Fatica and Prammer 2018).8

If housing is treated as a (very) durable consumption good, then it should be subject to VAT. Indeed, new buildings are subject to VAT in most EU member states. However, the upfront acquisition price might be a bad proxy for the stream of services for very long-lived products such as housing. Hence, as indicated by the Mirrlees Review (Mirrlees et al., 2011) an annual tax related to the consumption value of the property is a more effective way of taxing housing. It accounts for changes in the value of housing services and can be applied to the existing housing stock.9 Practically, recurrent property taxes or imputed rent taxation, adequately reflecting the (consumption) value of the property, would do the job efficiently.

Taxation of real estate focusing on one specific type of tax

Most of the literature on immovable property taxation focuses on one specific type of tax and assesses its merits and drawbacks with respect to i) efficiency and effectiveness considerations, ii) fairness/equity considerations, iii) fiscal federalism considerations and iv) political economy considerations. Recurrent property tax on residential property has been in the focus of the literature, while property transfer taxes have gained more attention recently, in particular as a possible tool for macroprudential policy.

The long-standing tradition of recurrent property taxes lies in their transparency, their relative ease of administration, their suitability as a stable revenue source for sub-central governments and their economic efficiency. International organizations such as the EU and the OECD keep requesting that taxes are shifted from distortionary labour taxation to property taxation on efficiency and equity grounds. Indeed, recurrent property taxes are usually found to be among the least detrimental taxes for economic growth (Arnold 2008), while at the same time they respect equity objectives (Cournède et al 2013).

However, in most member states property taxes are not levied on recent up-to date market values but on outdated cadastral values (compare section 1) and are sometimes area-based. While this limits the risk of tax-induced under-investment in housing and moreover stabilizes property tax revenues for member states, this very feature of the property tax design has been heavily criticized. First, market developments are not reflected and therefore the tax cannot contribute much to dampening the boom-and-bust-cycle of property markets and is thereby limited in reducing the fluctuations in the economy.10 Second, the tax is not perceived as fair or progressive. Those made relatively wealthier by the market or enjoying more neighborhood amenities (which should be capitalized into house prices) compared to the time when the cadastral value was set, pay the same property tax as those with stagnant property values. A tax on property value is not linked to current income, which makes it particularly burdensome for income-poor-housing-rich households such as senior households.

Given the practical shortcomings of the recurrent property tax, economists have repeatedly issued reform suggestions, to reap the full theoretical benefits of a recurrent property tax. Among the most frequently expressed reform necessities is the need to update the tax base to market values to increase the fairness of the tax (Norregaard, 2013; Slack and Bird, 2014; Blöchliger, 2015). The issue of equity/distributional reservations could be handled with an increase in the progressivity of the tax design e.g. by exemptions or property tax credits (based on income) for low income households or progressive tax rates. Tax deferrals for retirees would strengthen the ability to pay principle for senior households (Slack and Bird, 2015). A more radical approach has been put forward in work by the OECD11 suggesting taxing immovable property through the income tax system, via the taxation of imputed rents jointly with income from other sources.

While reform proposals are manifold, actual recurrent property tax reforms remain limited in number and size. This might be due to two factors: i) fiscal federalism frameworks and ii) political economy considerations. As recurrent property taxes are usually devolved to sub-central governments, any change of the property tax design might result in the need to change inter-governmental transfer schemes (Blöchliger, 2015; Norregaard, 2013). Even if a properly designed reform alleviated some of the political economy reservations such as perceived regressivity and unfairness due to outdated market values or issues for liquidity-constrained households, the property tax remains a presumptive tax, based on estimated (market) values. As property tax is capitalized into property prices, any reform would generate winners and losers, where generally losers are more vocal, resulting in “tax revolts” (Blöchliger, 2015). Hence, Slack and Bird (2014) explain the limited appetite for property tax reforms by political considerations outweighing economic principles, as stability is often favoured over equity and efficiency.

The ample literature on immovable property taxation can be grouped into two strands: the first strand covers the taxation of one type of real estate over its life cycle, such as owner-occupied housing. The second strand assesses the pros and cons of one particular tax on immovable property at a specific point in time, such as recurrent property taxation.

While grouping the literature along these lines is straightforward, summarizing the findings is less obvious. The first strand of the literature agrees that immovable property taxation should be neutral to avoid distortionary behaviour. However, the neutrality benchmark to be chosen depends on the theoretical view taken. Immovable property could be taxed as an investment – for private or business use – or as a consumption good, which determines the benchmark and possible distortions.

The second strand assesses one type of tax at a time with respect to its pros and cons. The focus is usually on efficiency considerations of immovable property taxation, while other aspects such as equity, fiscal federalism and political economy considerations, have gained less attention. Given the trade-offs between these aspects, the relevant literature does not seem to allow for a general “best immovable property tax” ranking, since the overall effect of a tax ultimately depends on its exact design and the overall tax system. Moreover, as indicated in the first strand of the literature, the overall effect of immovable property taxation also needs to be assessed over the object’s life cycle.

However, the literature in both strands seems to conclude that (recurrent) property taxation on residential property has a lot of theoretical merits, but that its practical application departs significantly from the theoretical best practice (Slack and Bird 2014, 2015). This assessment is particularly true for the EU given its generally low recurrent property taxation (based on outdated cadastral values), and its tax-preferential treatment of owner-occupied housing (on account of the under-taxation of housing equity) relative to other investments. Hence, the relevant literature asks for bringing practice closer to theory while at the same time carefully overcoming political economy considerations which might act as reform obstacles.

Arnold J., 2008. Do tax structures affect aggregate economic growth? Empirical evidence from a panel of OECD countries. OECD Working Paper No. 643

Barrios S., Denis C., Ivaškaitė-Tamošiūnė V., Reut A. and Vázquez Torres E., 2019. Housing taxation: a new database for Europe, JRC Working Papers on Taxation and Structural Reforms No. 08/2019, European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Seville

Blöchliger, H., 2015. Reforming the Tax on Immovable Property. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1205.

Brzeski, J., Románová, A. and Franzsen, R., 2019. The evolution of property taxes in post-Socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, ATI Working Paper WP/19/01, African Tax Institute, University of Pretoria.

Cournède, B., Goujard, A., and Pina, Á., 2013. How to achieve growth-and equity-friendly fiscal consolidation? A proposed methodology for instrument choice with an illustrative application to OECD countries. OECD Journal: Economic Studies, 13(1).

Fatica, S., and Prammer, D., 2018. Housing and the tax system: how large are the distortions in the euro area? Fiscal Studies, 39(2), pp. 299-342.

Johannesson-Linden, A., and Gayer, C. 2012. Possible reforms of real estate taxation: Criteria for successful policies. European Economy, Occasional Papers No, 119

Mirrlees, J., Adam, S., Besley, T., Blundell, R., Bond, S., Chote, R., Gammie, M., Johnson, P., Myles G., Poterba J., 2011. Tax by Design: the Mirrlees Review. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Norregaard, M. J., 2013. Taxing immovable property revenue potential and implementation challenges, IMF Working Paper, No. 13-129. International Monetary Fund.

Oliviero, T., Sacchi, A., Scognamiglio, A., & Zazzaro, A. 2019. House prices and immovable property tax: Evidence from OECD countries. Metroeconomica, 70(4), pp. 776-792.

Poghosyan, M. T. 2016. Can property taxes reduce house price volatility? Evidence from US regions. International Monetary Fund.

Slack, E. and Bird, R. M., 2014. The political economy of property tax reform. OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism, No. 18, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Slack, E. and Bird, R. M., 2015. How to reform the property tax: lessons from around the world. Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance.

This policy note is based on the article Immovable property: where, why and how should it be taxed? A review of the literature and its implementation in Europe. Public Sector Economics, 44(4), 483-504 by Doris Prammer. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

However, in Croatia a so-called ‘communal fee’ on properties based on their surface area is levied.

Italy does not levy recurrent property taxes on the primary residence since 2017.

Following a constitutional court ruling Germany had to adjust its property tax law – with respect to its cadastral values – by the end of 2019. The new law (property values) will become effective from 2025.

According to Johannesson-Linden and Gayer 2012 FN 6, BE, ES and IT tax imputed rents only for other than main dwellings. LU taxed imputed rents until 2016, which were calculated based on the cadastral value; the NL use the market value of the property as the tax base, but the resulting imputed rents are usually lower than market rents.

The mortgage financing of business property is usually tax deductible in all member states.

Tax bases for real estate property when bequeathed are very heterogeneous in member states and tax rates vary considerably among groups of heirs and property value.

As the paper focuses on the intensive margin of housing consumption decision, the excess consumption refers to the size of housing.

This is particularly important when the transition to a VAT for new housing would introduce considerable distortions between new and old housing or lead to lock-in effects if applied to all housing transfers (Mirrlees et al 2011).

Poghosyan (2016) has found a limited dampening effect of recurrent property taxes in the US, where recurrent property taxes are levied on property market values. Oliviero et al (2019) find a strong negative relationship between increases in immovable property tax revenues and house prices for a panel of OECD countries.

For a summary on this OECD work see Blöchliger (2015).