Finland has experienced three crises during the last three decades. In the early 1990s, Finland went through a banking crisis and a simultaneous loss of its biggest export market with the collapse of the Soviet Union. After significant depreciation of the Finnish markka and thanks to the vigorous growth of the ICT sector, Finland recovered from the depression. The Global Financial Crisis and the following European sovereign debt crisis did not result in a banking crisis in Finland. However, due to a large number of more or less idiosyncratic developments, the Finnish economy lost a decade of growth in 2007-2017. As the single monetary policy was extremely accommodative throughout the years of slow growth, domestic demand could, nevertheless, be maintained to a much greater extent than in the previous crisis. Finally, the ongoing corona crisis exposes Finland to yet another type of economic challenge. Domestic demand crashed due to unprecedented uncertainty and lockdown measures to contain the health crisis. This has been addressed by unforeseen fiscal measures and monetary policy accommodation. Yet, for an open economy like Finland the second wave is still looming ahead. Even if the virus itself could be contained, the fall in external demand is likely to prolong the crisis.

The focus of this article is on monetary policy in the (financial) crises Finland has gone through in the past decades. Since 1999, Finland has been part of the common currency area applying single monetary policy together with a growing number of other EU member states. Therefore, when dealing with the Global Financial Crisis we are by and far discussing the monetary policy of the ECB. We review the Finnish performance as a member of the euro area in the Global Financial Crisis against the backdrop of the domestic (or Nordic) banking and economic crisis in the early 1990s. Seemingly, some lessons had been learned facilitating Finland in coping with the Global Financial Crisis, but some had not.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the euro area addressed weaknesses that had made it vulnerable in the crisis. However, the ECB couldn’t normalize its monetary policy, and fiscal policy could have been more countercyclical, also in Finland, before the corona pandemic hit the euro area in early 2020. Fear and uncertainty about the virus as well as the containment measures to address the health crisis caused a sharp drop in economic activity in the spring 2020 globally, in the euro area, and in Finland. The current crisis has not (yet) turned into a financial crisis but has, however, caused financial stress also in the euro area. Operating at the effective lower bound of interest rates and with very high initial indebtedness in the public finances brings about additional challenges for the euro area and its countries in managing the ongoing crisis.

The severe recession in Western Europe in the beginning of the 1990s turned out to be most severe in the Northern periphery of the continent. Finland and Sweden experienced a typical boom-bust cycle where both monetary and fiscal policies played a role first in creating and then in alleviating the crisis. The focus here is on Finnish experiences although the crisis was very similar in Sweden.

Initially, Finland applied fixed exchange rates policy and the Finnish financial markets were strongly regulated. In the boom phase in the latter half of the 1980s, financial deregulation together with low real rates of interest initiated rapid credit expansion.

As a result of the liberalization of capital movements and phasing-out of interest rate controls, bank lending doubled during the latter half of the 1980s. The real interest rate was low and the real after-tax interest rates were barely positive thanks to the deductibility of the interest rate expenses on bank loans. The relatively high nominal interest rates were not high enough to dampen credit-fueled demand. Also, lending in foreign currency rose dramatically. The inflow of foreign capital increased liquidity and fueled the domestic credit expansion, also exposing many SMEs to foreign exchange risk.

During the boom, the unemployment rate was way below the estimate of the natural rate, at just above 2 per cent, and the sharp increase in asset prices increased household wealth. There was rapid growth in consumption and investment. High wage increases led to weaker foreign competitiveness and growing trade deficits.

In order to dampen the boom, the Bank of Finland raised interest rates slightly in 1987-89. The impact of these actions was, however, of limited significance since the tightening of domestic monetary conditions was offset by the inflow of foreign capital. Since monetary policy was committed to fixing the exchange rate for the Finnish markka, more responsibility for stabilizing the economy fell on fiscal policy. However, fiscal policy was too loose to restrain rapid growth and the widening of the current account deficit.

At the same time, foreign investors started to have doubts about the sustainability of the exchange rate peg. In March 1989, the Bank of Finland revalued the markka to dampen inflation, but this contributed, at the same time, to the overvaluation of the Finnish markka.1 By making imports cheaper, it deteriorated the country’s terms of trade, and further widened the current account deficit.

The boom ended abruptly in 1990 as higher real rates of interest led to falling asset prices, falling profits and increasing savings. The exchange rate was still overvalued while GDP and employment continued to fall. As devaluation was ruled out from policy options for political reasons2, the government tried to resort to incomes policy measures. To address the shock, a rapid and large reduction of labour costs either by an internal devaluation or a depreciation of the external value of markka was needed.

When it became apparent that the social partners couldn’t agree on cutting nominal wages, the credibility of the exchange rate peg collapsed. Facing rapid currency outflows, the Bank of Finland tried to support the exchange rate by raising interest rates, but this was not enough to stop the run on the Bank’s foreign reserves. The credibility of the peg was further weakened, and finally Finland devalued the markka in November 1991.

The Finnish economy experienced an unprecedented wave of bankruptcies, credit losses in the banking sector, and a fall in house prices. Despite the increasingly restrictive fiscal measures, fiscal deficits widened and the development of public debt turned explosive. The corporate sector responded to the crisis by cutting costs and selling off assets. This further sharpened the debt deflation spiral in the economy.

Eventually, the markka was left to float in September 1992. Its value immediately fell by about 10 percent and depreciated by a further 20 percent in subsequent months. As interest rates were subsequently reduced, the crisis started to calm down and the recovery started.

The stable (or strong) markka policy has been debated extensively in ex-post analysis of the depression of the 1990s. The policy was partly supported by developments in economic theory which stressed the role of credibility and rules. The new theories suggested that monetary policy-makers should concentrate on fighting inflation as an anchor for economic policy instead of fixing the FX rate – i.e. aiming at domestic instead of external price stability. In practice, the experience of well-functioning financial markets under pegged exchange rates and free capital flows was rather limited. The crisis was a clear illustration against trying to combine international capital mobility, a fixed exchange rate and monetary policy sovereignty, commonly known as the impossible trinity or the trilemma for an open economy.

An important lesson from the 1990s crisis was that indebtedness and financial risks within the private sector have to be more closely supervised. Credit expansion had not been controlled and during the crisis the government was forced to socialize a large part of the losses caused by the debt deflation process. Consequently, a new Financial Supervision Authority was created in 1993 into the proximity of the Bank of Finland. Another lesson is that, in addition to flow variables, also the financial stocks such as the assets and liabilities of households and firms deserve great attention. The crisis showed that public debt to GDP can suddenly jump due to excessive leveraging in the private sector. This applies to the banking crisis in Finland, but also to the housing market boom and bust in Spain and Ireland that started to build up.

Recovery, EU accession and the road to the euro area

The long recovery was facilitated by a sharp depreciation of the markka and the rapid fall in the short- and long-term interest rates. The recovery was also sped up by the rapid growth of the ICT sector led by the Nokia cluster which boosted the productivity and competitiveness of the Finnish economy. Finland adopted an inflation target in 1993, and three years later, decided to join the euro area among the first participating countries. Finland joined the exchange rate mechanism of the European Monetary System in 1996, and eventually in 1999 the markka was replaced with the single currency.

In the latter half of the 1990s, lower interest rates and the previous budgetary cuts created new leeway for policy-makers, who used the higher-than-expected tax revenues to finance tax cuts and increase public spending. In the environment of falling real interest rates, improved competitiveness and growing employment, expansionary fiscal policy was no threat to fiscal stability. The spectacular improvement in fiscal balances achieved in 1995-2000 was caused not by fiscal tightening but rather by strong growth, lower interest payments and declining unemployment-related expenditures.

Before the financial crisis, the dominant central bank model in most advanced economies was that of an independent central bank pursuing price stability within an inflation-targeting approach by moving interest rates according to some version of the Taylor rule3. This meant in practice that financial stability was not an integral element of central banks’ objectives. That is, financial stability was more seen as a precondition to price stability rather than a separate goal.

The global financial crisis that started in 2008 in the euro area was not different from previous crises. Also this time, the economic developments preceding the crisis were characterized by excess credit growth.

In the first decade of the euro area, the benign economic developments of its 12 member states masked factors that laid the ground for a financial crisis. The first of them is the mere fact that the economic developments were so benign. The two decades preceding the financial crisis are characterized in advanced economies by “Great Moderation”. Steady growth in income per capita was combined with decreased volatility of macroeconomic aggregates. The volatility of output, employment and inflation decreased not only in the euro area but also in the United States, Japan and the UK. These developments lowered crisis awareness in general, and allowed macroeconomic and financial imbalances to grow under the surface.

Macroeconomic imbalances emerged globally, but they took different forms in the euro area and the US. The common feature was high credit growth. In the euro area, the ranking of countries in terms of the increase in the ratio of credit to income broadly corresponds to the ranking of severity of the subsequent crisis. The global dimension of credit growth was visible, in particular, in the huge current account deficit of the USA, matched by the huge current account surplus of China since the end of the 1990s.

In the euro area, imbalances developed between core and periphery countries. Price and wage inflation were faster in the periphery than in the core countries, which thanks to the single monetary policy resulted in lower real rates in the periphery, and hence, facilitated the build-up of excess credit. The full convergence of nominal interest rates and partial convergence of inflation (and inflationary expectations) meant that the behavior between the financial and the real sector was asymmetric. At that time sovereign spreads between euro countries were very small, i.e. they did not reflect the build-up of imbalances. Rather, macroeconomic imbalances were reflected in the divergent development of the euro area economies’ external balances (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Current account balances of selected euro area countries, percentage of GDP

While central banks have a very holistic view of the financial system, the limited responsibilities they had in financial stability before the financial crisis meant that this view did not translate into a macro approach in regulation and supervision. Macroprudential policies were still to be discovered.

In retrospect, it is easy to say that the signs of an approaching financial crisis were present way before the crisis materialized. Financial cycles and the theory of multiple equilibria tell us that an economy is prone to sharp changes for minor causes, once the country has reached the danger zone, where its fundamentals are consistent with both the good and the bad equilibrium.

In the Global Financial Crisis, Finland benefited from the long shadow of its domestic banking sector crises less than twenty years earlier. The banking sector was in good shape after the major restructuring that took place in the 1990s crisis. Also the corporate sector’s balance sheets were much stronger than before the domestic crisis. Households’ mortgage credit had grown roughly hand in hand with disposable income and the public sector’s debt to GDP ratio had been brought down to around 35%. Thanks to these developments Finland was able to maintain a high sovereign rating throughout the crisis, which again helped banks to receive cheap liquidity from abroad. As a result, the global financial crisis did not manifest itself as a financial crisis in Finland, but rather as a huge shock to external demand.

Finland was one of the best performing economies of the world in the decade preceding the global financial crisis. The success was largely driven by the ICT sector, in particular the performance of Nokia. The performance of the Nokia cluster was first reflected in rapidly improving cost competitiveness measured by the real effective exchange rate and a large surplus in the current account (over 5%/GDP on average in 1999-2008). Finland’s terms of trade were, however, steadily decreasing as the price of mobile phones on the international market fell, and the terms of trade adjusted cost competitiveness was rapidly deteriorating before the financial crisis. This was not understood to a sufficient degree by social partners and policy makers, and consequently general wage increases were agreed in line with the overall REER. The strong reliance of the favourable economic development on one sector together with a lack of flexibility to adjust turned out to be one of the key vulnerabilities of Finland in the subsequent crisis.

Before the crisis, three key assumptions determined the conduct of monetary policy4:

In the crisis, these assumptions fell one by one.

First, at the start of the financial crisis, the demand for liquidity grew significantly and irregularly as banks wanted to hoard liquidity for precautionary purposes. Consequently, the central bank’s control over the short term rates weakened.

Second, the transmission from the short-term risk-free rate to the rates more directly relevant for the economy became less efficient. For example, the widening of the spread between the Euribor and the Overnight Interest Swap (OIS) rates at all maturities meant a sudden increase in the borrowing costs of economic agents just when the crisis would have called for monetary easing.

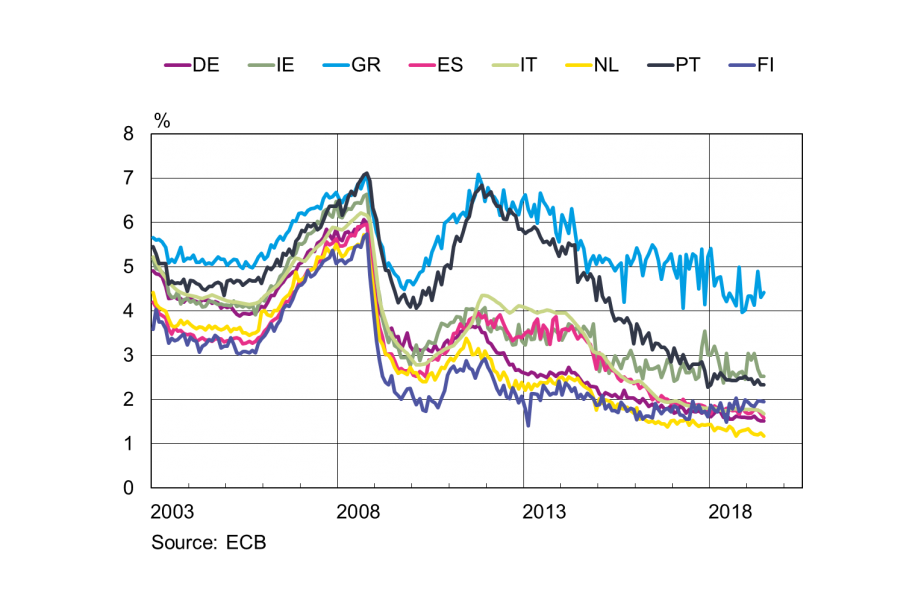

Also, in the European sovereign debt crisis, the cost of financing of small and medium-sized enterprises increased substantially in peripheral countries compared to the core, reflecting the impaired transmission of monetary policy. This impairment was largely driven by the developments in the sovereign spreads. Hence, monetary policy easing manifested itself conversely to its needs. Even though the ECB was increasing monetary policy accommodation, the monetary conditions tightened in countries which were most severely hit by the crisis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Composite lending rate on loans to non-financial corporations, core vs. periphery

The third key condition for conducting monetary policy before the financial crisis, namely the ability of the central bank to adjust its interest rate in line with the needs fell when the steering rate hit the zero lower bound (ZLB) at the end of 2014.

Central bank responses

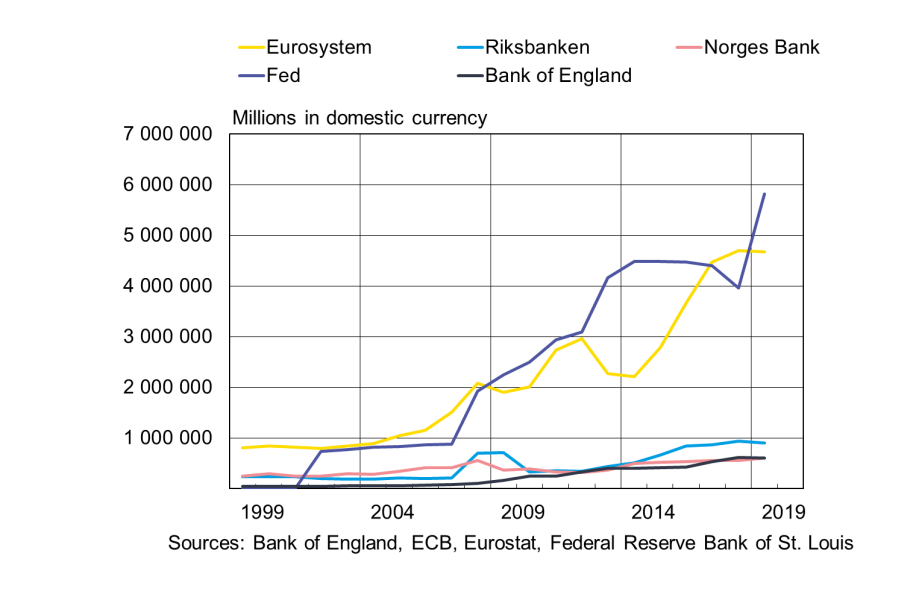

The ECB reacted to the three key challenges by changing its operational procedures and in particular by engaging in balance sheet management (Figure 3). Balance sheet management deals both with the length of the balance sheet (quantity) as well as the quality of its asset side in particular. With the new measures, the ECB regained the control of the short term rates, facilitated to bring order in the spreads between the policy rate and more macro-economically relevant interest rates and indeed brought extra monetary policy accommodation when the short term interest rate had reached its lower bound.

Figure 3. Central Bank balance sheets in the euro area, the US, UK, Sweden and Norway

Concerning the operational framework, ECB managed to tackle with volatility in the banks’ demand for liquidity by switching liquidity provision from variable-rate to fixed-rate tenders with full allotment. That is, by fixing the price of central bank reserves and letting their supply to fully adjust to banks’ demand, the ECB isolated the short-term interest rate volatility from the unpredictable changes in the demand for liquidity. This change effectively addressed the reduced control of the operational target.

The impaired monetary policy transmission from short-term rates to rates more directly relevant to the real economy, was addressed, first, by shifting bank refinancing from short term liquidity provision to increasingly longer term funding. Eventually, the ECB provided banks with funding for up to four years and at rates even below the rate it paid for holding liquidity at the central bank’s deposit facility. To facilitate the pass through of the monetary impulse, the cheapest form of funding required the banks to increase their lending to the real economy.

Concerning the impairments in the sovereign bond markets, the ECB conducted initially smaller asset purchase programmes to support the impaired sovereign bond markets. However, the real game changer in this sense was the ECB President’s famous pledge to do “whatever it takes”, and the subsequent Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme that operationalized the commitment.

To deal with the zero lower bound, ECB engaged in three types of monetary policy responses: First, with Forward Guidance the ECB brought the expected lift off from the lower bound forward in time, hence, pulling the longer-term interest rates down. Second, by engaging in large scale asset purchases (QE), the ECB lowered financing costs in general and secured the flow of credit to the real economy. Third, by lowering the policy rate into the negative territory, the ECB evidenced that the true effective lower bound for nominal rates was below zero. With these non-standard monetary policy measures, the ECB managed, at least partly, to address the lack of leeway to adjust the traditional tool. Yet, even though many new measures were introduced, the ECB did not manage to lift medium term inflation expectations to its inflation aim before the crisis hit the global economy. Consequently, there is room for rethinking the ECB monetary policy strategy, as already decided by the ECB’s Governing Council.

The impact of the Great Recession was hardest on peripheral European economies, as many of them had let themselves to drift into a vulnerable situation over the preceding years. These developments turned the spotlight on their fiscal positions, the health of their banking sectors and in particular the interaction between the two. Sustainable fiscal policy is a key condition for everyone, but especially for a sovereign participating a common currency. The public debt to GDP ratio decreased in the euro area during the recovery from the Global Financial Crisis in 2013-2019, but deleveraging has been moderate and uneven across member states.

The negative feedback loop between sovereigns and their national banking sectors manifested itself severely during the euro area sovereign debt crises. To address this, a European banking union (BU) was created with Single Supervisory Mechanism and Single Resolution Mechanism as integral parts of it. Yet, the third pillar to complete the BU is still missing; i.e. the European Deposit Insurance Scheme is still on the drawing board of the policy makers. In this sense, stability would be further increased if banks in the euro area operated more across national borders.

For Finland, the Great Recession was only one problem among many others in the past decade’s economic development. The Global Financial Crisis was for Finland a large negative shock on external demand but it did not cause large-scale financial stress in the domestic economy nor in the banking sector. Together with i) the collapse of the ICT sector, ii) the downward trend in the forest industry, iii) the shrinking of the working age population, iv) the problems of the Russian economy and v) deteriorated cost competitiveness it however resulted in a decade of very poor productivity growth and output levels that did not reach the pre-crisis levels before 2017.

As part of the single currency area, Finland lacked its traditional macro tool to deal with large economic shocks, i.e. the terms of trade could not be improved by a competitive devaluation or depreciation. Despite wage moderation and an internal devaluation cost competitiveness has still not returned to the levels preceding the Global Financial Crisis. However, as the single monetary policy was extremely accommodative throughout the years of slow growth, it is not at all obvious that this kind of monetary conditions could have been maintained outside the euro area. Monetary policy has supported Finland both directly and through reviving euro area growth.

The keys to economic success as part of a large currency area seem to be the same as everywhere: i) sustainable public debt and sound fiscal policy guarantees effective flow of funding to the economy and consequently the room for automatic stabilizers to work even in a severe downturn, ii) flexibility in the labour markets can compensate the lack of own FX rate to adjust for negative shocks, and iii) neither domestic nor single monetary policy can be seen as a substitute for structural reforms as a source of sustainable economic growth.

In the spring of 2020, global economic activity experienced a sharp drop due to the corona pandemic. GDP for the euro area is expected to fall by almost 9% this year.5 Similarly, according to the Bank of Finland’s baseline forecast, Finnish GDP is about to decline by 7% in 2020. In an alternative scenario with a strong resurgence of the virus, the drop in activity in both the euro area and Finland may be intensified to more than 10%.

The ongoing global slump, exposes Finland to yet another type of economic challenge. This time domestic demand crashed due to unprecedented uncertainty and the lockdown measures to contain the health crisis. Service sectors were first and most severely hit. However, at the time of writing, their prospects seem to improve rapidly with the dissipation of fears associated with the spread of the virus and the removal of the lockdown measures.

The crisis has been rapidly addressed in Finland, in the euro area and globally with unforeseen fiscal measures and monetary policy accommodation. Yet, the success of these measures will depend greatly on the behavior of the virus in the future. A great deal of uncertainty needs to be resolved for savings to normalize and firms to have restored faith in investment opportunities. Moreover, for an open economy like Finland, a second wave of the crisis is looming ahead even if the virus itself could be contained, as our external demand is likely to take a big hit in the near future.

The pandemic seems to call for both new and standard measures especially from the fiscal authorities. Furthermore, the timing of the implementation of the measures is essential. In the acute lockdown phase, the role of economic policy is bridge-building for households and businesses. It is crucial to avoid a big wave of bankruptcies and mass unemployment. Once the lockdowns are relaxed and consumers and firms regain confidence, a need for more traditional stimulus both from fiscal and monetary policy authorities continues for some time. However, to guarantee the long run sustainability of public finances, economic policy must soon turn to structural issues both in order to enhance growth and productivity as well as to adjust public expenses.

The governments’ efforts to alleviate the economic effects of the virus will result in a new jump in public debt levels in the euro area. Thanks to the new Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, the ECB has, so far, prevented a financial crisis, but the possibilities to speed up the recovery and to reach the inflation aim in the medium term are somewhat limited. The Bank of Finland is eager to participate actively in the monetary policy strategy review to overcome at least some of the challenges looming ahead. Being a member of the Eurosystem, our possibilities to impact European policy making are much greater than they were when we were running domestic monetary policy.

The pandemic has brought about unprecedented uncertainty. The outlook for both the evolution of the virus as well as for its economic consequences is blurred, and the consequences for the conduct of monetary policy are still far from certain. In addition to the pandemic, also uncertainties in global trade have been looming in recent years. Now, in times of large uncertainties, being part of a larger economic entity like the euro area, is likely to increase stability for a small open economy like Finland.

Englund, P. and V. Vihriälä, (2008), ”Financial crisis in Finland and Sweden: Similar but not quite the same”, Chapter 3 in Jonung L., Kiander J. and Vartia P. (2009): “The great financial crisis in Finland and Sweden – The Nordic Experience of Financial Liberalization”, Edvard Elgar Publishing Limited.

Papadia F., Välimäki T. (2018): “Central Banking in Turbulent Times”, Oxford University Press.

In those days, Finland was one of the (if not the) most expensive country in the world according to Purchasing Power Parity comparisons.

Eventually, the Finnish markka was pegged unilaterally to the European Currency Unit, ECU, in early 1990.

See Papadia & Välimäki (2018) for a comprehensive review of changes in central banking over past decades and for a richer treatment of ECB’s monetary policy in Great Recession in particular.

For a richer treatment see Papadia and Välimäki (2018).

See “Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, June 2020” https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/projections/html/ecb.projections202006_eurosystemstaff~7628a8cf43.en.html#toc3.