As the number of Covid-19 cases has mostly stabilised across the EU, economic recovery has become the main challenge in most countries. The government responses to the pandemic have an unprecedented fiscal impact. Overall, EU member states approved already more than 350 different Covid-related fiscal measures. According to recent macroeconomic forecasts, Independent Fiscal Institutions estimate the budget deficit in 2020 to be on average 8% of GDP. The Gross Public Debt is expected to rise by an average 14%-15% of GDP in 2020. This European Fiscal Monitor policy note based on information from national IFIs provides an overview of fiscal measures taken in response to Covid-19 in 25 EU member states2 and the UK, as of end of May 2020.

As the number of Covid-19 cases has mostly stabilised across the EU, economic recovery has become the main challenge in most countries. EU fiscal councils estimate a decline in real GDP of between -2% to -13% in 2020. It is unclear whether EU economies will fully recover by the end of the 2021, particularly if there is a second wave of infections.

The Commission has introduced several initiatives to mobilise funds and support economic recovery. Some of them are already adopted (SURE), while others are still pending (European Recovery Plan etc.). In the meantime, member states have carte blanche to boost public spending to support their economies.

Overall, EU member states approved more than 350 different Covid-related fiscal measures. Of these, nearly half are fiscal expenditures. As of May 2020, EU countries expect to increase their spending by 3% of GDP on average. Additionally, member states anticipate foregoing an average 1% of GDP in revenues, which will further worsen their fiscal deficits.

According to recent macroeconomic forecasts, fiscal councils estimate the budget deficit in 2020 to be on average 8% of GDP across EU member states. The Gross Public Debt is expected to rise by an average 14%-15% of GDP in 2020.

This Special Update Edition of the European Fiscal Monitor provides an overview of fiscal measures taken in response to Covid-19 in 25 EU member states3 and the UK, as of end of May 2020.

All EU member states with restrictions in place are now slowly exiting lockdown. Travelling restrictions are being lifted and more and more venues and shops are opening their doors to customers. At the same time, schools and universities remain closed in some member states while large-scale events and gatherings are still prohibited in most EU countries.

As of 31 May 2020, 19 out of the 25 member states have triggered national escape clauses to suspend national budgetary restrictions.4

Although in most countries escape clauses were triggered only for the fiscal year of 2020, some member states have suspended their fiscal rules for more than one year. For example, Czech Republic increased the structural deficit ceilings from 1% to 4% for 2021, with a gradual yearly decrease of 0.5% points until 2027. This decision was debated for almost a month and faced much criticism, including from the Czech Fiscal Council.

Italy has approved an additional package of structural deficit deviations extending to 2032. The so-called safeguard clauses meant to automatically increase VAT and excise duties are suspended for the same period. Finland activated escape clauses for a shorter period: expenditure ceilings are suspended until 2022. This would provide additional flexibility for public spending of up to EUR 0.5 billion per year.

The daily activities of most fiscal councils are still affected by the crisis. Apart from teleworking and other administrative arrangements, IFIs are also feeling the additional workload related to analysing the economic and fiscal impacts of the crisis. Some face staff shortages where states oblige public sector employees to use paid leave.

Many fiscal councils are closely monitoring the implementation of new fiscal measures and estimating their budgetary impact. Nearly all members of the Network have had to update their publications to account for changes in macroeconomic projections. Numerous publications have been put on hold due to resource shortages.

Some of the difficulties were related to the assessment of the modified Stability and Convergence Programs (SCPs) and overall delays in the endorsement timelines. The content of the SCPs was simplified by the Commission and some traditional indicators were omitted. Instead, member states had to detail their Covid-19 response and provide estimates on the budgetary impact of new fiscal measures. Three member states submitted the SCPs with a delay: Denmark and Portugal within one week after the deadline and Slovakia within two weeks.

Some 15 out of 26 fiscal councils have also updated their macroeconomic forecasts. Of these, the Danish Economic Council has a mandate to prepare an alternative forecast and seven5 have a formal role in assessing forecasts.

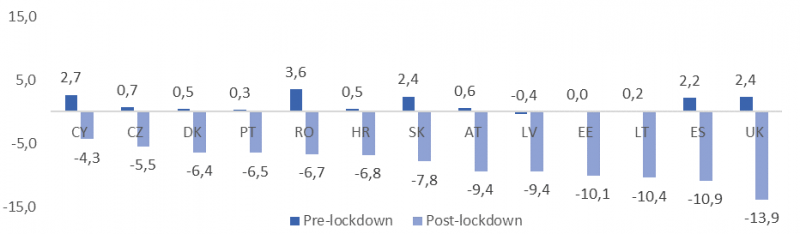

The impact of Covid-19 on Europe’s economies is substantial. EU Independent Fiscal Institutions initially projected real GDP to grow on average by 2% in 2020. As the forecasts were updated mid-crisis the real GDP projections fell by on average 9% in 2020 to -7.5%, ranging from -1.9% (RO) to -12.8% (UK).

Following the activation of fiscal escape clauses at both national and EU levels, member states made use of their fiscal space to introduce support packages of unprecedented size. Nearly half of all adopted measures (176 out of 356) have a direct impact either on the expenditure or revenue side of the fiscal budget, which leads to worsening budget balances and an increase in public debt both in 2020 and potentially later on.

Fiscal councils estimate a reduction of 9% in the budget deficit from an average surplus of 1.2% before the lockdown measures to a budget deficit of 8.3% in 2020 in the projections at the end of May (see Figure 1). The UK is expecting the highest budget deficit – at more than 16%.

Figure 1. Projected budget deficit (% of GDP)

Source: European Fiscal Monitor

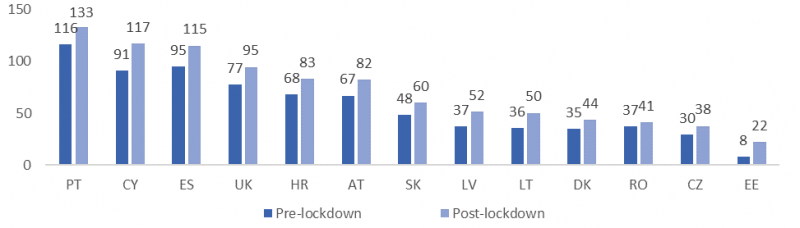

To finance the Covid-19 measures EU countries plan to increase their borrowing by 14% on average (see Figure 2). The largest increase in debt-to-GDP ratio is projected in Cyprus (+25.7%). Austria, Croatia, Portugal, Spain and the UK all project an increase in their debt ratio of more than 15%. Romania has the smallest projected increase of 3.8% as their fiscal response is constrained by the Excessive Debt Procedure launched in March 2020.

Figure 2. Projected public debt (% of GDP)

Source: European Fiscal Monitor

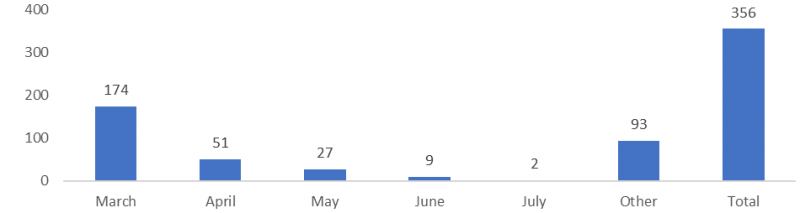

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, 26 countries have together approved more than 350 measures (see Figure 3). The bulk of these were put in place in March-April. Most measures were part of the immediate response to the crisis (160) and aimed to remedy economic contraction, support company liquidity and avoid unemployment. Additionally, a minority of countries (10)6 implemented a total of 20 measures targeting the health sector as part of their immediate response to the crisis early on.

As countries are now slowly lifting lockdown measures they are also adopting fewer fiscal measures. Only around one-tenth of all measures were put in place in May to supplement those already active. Most aim to support economic recovery and smooth the transition to the new normal.

On average, EU member states and the UK each adopted around 14 Covid-related fiscal measures, including those with retroactive effect. Funds involved amount to around 13% of GDP per country, including contingent liabilities and fiscal measures stretched out for several years.

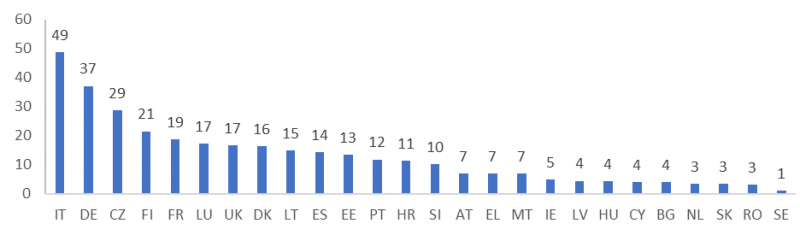

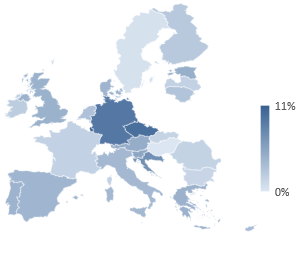

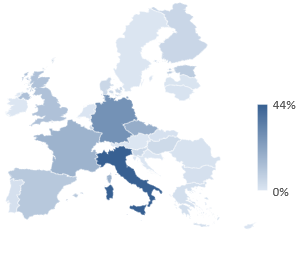

Czech Republic, Germany and Italy expect to have the largest fiscal response (see Figure 4). Italy introduced a total of 13 measures with a size of almost 50% of GDP, of which 44% are public guarantees that typically would not have a direct fiscal impact unless the guarantees are called. Similarly, in Germany, expected Covid-related measures amount to 37% of GDP, of which 25% are public guarantees. In Czech Republic state guarantees take up around 19% of GDP while the total fiscal response is expected to cost around 29%.

Romania, Slovakia and Sweden have adopted the smallest packages. Sweden implemented measures that amount to only 1% of GDP, which could be explained by the fact that Sweden did not impose a lockdown, unlike other EU countries. Romania and Slovakia committed around 3% of GDP to Covid-related fiscal measures.

Figure 3. Total number of Covid-19 related fiscal measures approved as of 31 May 2020

Notes: Other category includes measures with retroactive effect, in negotiation and those undefined.

Source: European Fiscal Monitor

Figure 4. Total size of expected fiscal response (% of GDP)

Source: European Fiscal Monitor

All countries resorted to measures with a direct budgetary impact. These measures, such as fiscal expenditure and tax relief, lead to worsening budget balances.

The fiscal expenditure measures aim to avoid unemployment and mitigate short-term corporate cashflow problems. All EU countries are granting financial aid to affected workers as well as to companies and the self-employed.

Moreover, a majority of countries (16) have increased their spending on national health sectors. These expenses are mostly public purchases of sanitary equipment and protective gear, healthcare staffing and compensation for extra hours. Some countries also aim to compensate health workers for extra hours or risk to contract the Covid-disease. Additionally, Spain and Finland have allocated 0.1% and 0.3%7 of GDP respectively for vaccine-related research costs.

Tax relief measures reduce the immediate burden for taxpayers. All countries have postponed some tax deadlines. These measures in part delay the receipt of tax revenues, but at the same time it is expected that the large majority of the amounts due will ultimately be paid.

The magnitude of the immediate fiscal response is unparalleled (see Figure 5). Most countries will increase their spending by around 3.1% of GDP and give tax relief for another 1.1% of GDP. Nearly all countries have budgeted these measures for a short term only (up to one year). This means that if funds are insufficient governments will have to extend or renew the fiscal stimulus. In total, seven countries8 have introduced open-ended packages with an estimated average size of 0.9% of GDP. In late March, Germany introduced the largest open-ended package to acquire capital instruments and finance economic recovery. As of May 2020, all funds devoted to this package (3% of GDP) were used. As the measure is open-ended its size could increase, if need be.

Luxembourg has the largest direct fiscal response, amounting to a total of 11.1% of GDP, of which 6.0% are fiscal expenditures and 5.1% tax relief. Czech Republic and Germany envisage direct fiscal responses of 9.9% and 9.2% of GDP respectively.

Figure 5. Direct Fiscal impact of COVID related measures (% of GDP)

Source: European Fiscal Monitor

Most common indirect fiscal measures are government guarantees on loans provided by financial institutions and loans disbursed directly by state-owned institutions. These measures aim to facilitate the access of companies and the self-employed to working capital, without incurring a large immediate impact on the fiscal deficit. Instead, the impact is spread over the entire maturity of loans and only occurs in the event of non-repayment. Given the impact of the shock and the expected longer period with low or negative economic growth that will follow, many lenders might struggle to repay the loans. This would have negative implications for public finances in the longer term.

Almost all countries implemented guarantees. The scale of this measure is largest among all categories of fiscal measures, with 6.3% of GDP on average (see Figure 6). The largest public guarantees were introduced in Italy, Germany, Czech Republic, France and Spain.

Figure 6. Indirect Fiscal impact of COVID related measures (% of GDP)

Source: European Fiscal Monitor

Most guarantees were put in place in March and April to facilitate companies’ access to capital and alleviate liquidity problems. These measures make up part of the immediate crisis response and economic recovery plans.

Countries mainly adopted short-term guarantees, but some member states9 (4) have measures for long-term guarantees. Bulgaria is the only country that has not implemented public guarantees but rather provides public loans.

Public loans were introduced in fewer countries (15). On average these countries have allocated around 0.5% of GDP. Germany and Estonia have allocated substantially more, with 3.0% and 2.7% of GDP respectively. Most of the public lending programmes implemented have a maturity of up to one year. However, there are also countries that issue medium-term and long-term loans: they will lend for up to five years. Moreover, Spain extended its public credit lines to SMEs and the unemployed indefinitely, as part of the open-ended package.

A minority of EU member states (7)10 have also decided to increase public investment in companies or infrastructure.11 For example, Finland is injecting capital into commercial papers, Latvia is increasing its share in the Riga Eastern Clinical University Hospital and Estonia is ready to increase its share in state-owned companies. Investment will cost around 0.2% of GDP per country.

Some countries have adopted other measures to mitigate the economic consequences of Covid-19. These are mostly changes to legislation, budget reallocation and credit moratoria.

In addition, some countries have facilitated the receipt of unemployment benefit, and outlawed evictions of tenants and seizures, etc. In the domain of prudential regulation, some countries have also relaxed the capital requirements for banks, thereby easing the lending to temporarily constrained borrowers.

Authors would like to thank Beatriz Pozo (CEPS) as well as members of the Network of European Independent Fiscal Institutions for their valuable contributions to this policy note.

AT, BG, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GR, HR, HU, IE, IT, MT, LT, LU, LV, NL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK.

AT, BG, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GR, HR, HU, IE, IT, MT, LT, LU, LV, NL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK.

AT, BG, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, FI, FR, GR, HR, HU, IT, LT, LU, LV, MT, PT, RO, SI.

AT, CZ, EL (PBO), IT, LT, LV, PT.

BG, EE, ES, FI, FR, IT, LT, LV, MT, UK.

Vaccine-related funding is part of the larger healthcare package in Finland, which includes public purchases of medical equipment and tests.

AT, CZ, DE, EL, ES, FI, FR.

DK, FI, EL, MT.

DK, EE, FI, IT, LU, LV, UK.

Not including state aid.