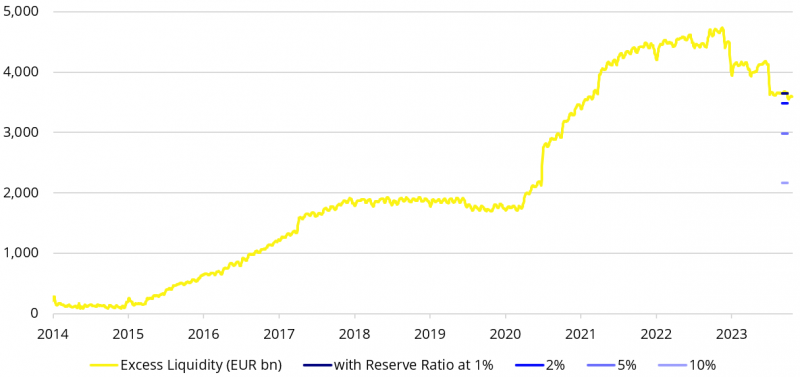

Figure 1: Euro area excess liquidity under various minimum reserve ratios

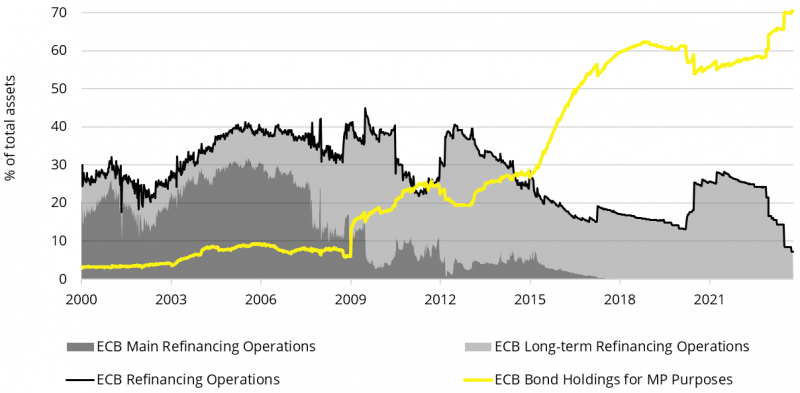

Figure 2: Towards a more balanced ECB asset mix: bond portfolio vs. refinancing operations

Source: Robert Holzmann proposed a minimum reserve ratio of between 5 and 10% in the German business magazine WirtschaftsWoche (WiWo) on September 27, 2023. Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji published a CEPR discussion paper (DP18103) “Monetary policies without giveaways to banks” in April 2023.