Central banks play a vital role in the global financial system. With a range of critical responsibilities and functions, they are integral to the smooth functioning of financial markets and the growth of national economies. Robust balance sheets provide central banks the resources to discharge their obligations effectively. Yet particular vulnerabilities expose central bank balance sheets to risks that can become acute during times of stress. These vulnerabilities arise because central banks must structure balance sheets differently from those of other institutions and because central banks’ functional obligations limit how they can manage risks arising from these structures. This paper focuses on the way that monetary gold holdings can mitigate the risks arising from the balance sheet anomalies, particularly during times of stress.2

During the 2007-09 global financial crisis, many national currencies appreciated sharply against the US dollar (USD), in response to the crisis. Given that the USD is the single largest foreign exchange (FX) reserve currency for most central banks, its relative weakness had a notable impact on their balance sheets.

In essence, when the USD loses value against national currencies, central bank balance sheets incur revaluation losses, which can erode their core equity when under extreme stress.

At times, this erosion reaches a level that requires central banks to ask their governments for recapitalization, prompting questions about their competence and often impeding their ability to operate effectively.

This phenomenon was clearly in evidence in the financial crisis. At that time, however, it became apparent that central banks holding monetary gold as part of their FX reserves seemed better able to preserve their equity positions than those which did not.3

As issuers of the national currency, central banks carry circulating currency as a zero-cost liability. Also, multiple policy objectives require commercial banks to hold balances in central bank accounts that earn little or no interest.4 These functions provide central banks with access to low-cost liabilities, which they invest in income earning assets. This keeps them profitable during times of economic stability or expansion.

Central banks are responsible for monetary policy and managing the nation’s foreign reserves. These obligations require them to structure their balance sheets in such a way that they carry risks not common to commercial entities. Their policy obligations limit the way they can hedge their exposures, compared to other financial institutions.

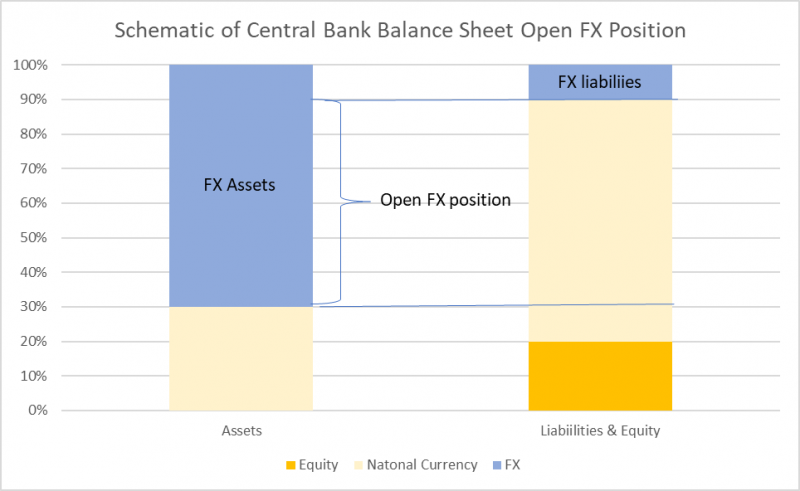

A central feature of central bank balance sheets is that they carry more foreign currency denominated assets than liabilities. This creates an open FX position that can have far-reaching implications.

We illustrate this in the schematic below.

Central bank equity should support the balance sheet during periods of economic turmoil. This equity usually consists of two tranches: statutory capital and revaluation reserves.5

First, the open FX positions create exposures to FX risk which may increase significantly in periods of economic strife. Second, central banks’ assets and liabilities are subject to different accounting treatments, which can further stress their balance sheets.

Both these features create volatility, which may stress the central banks’ equity. As discussed above, in certain circumstances, these stresses may force central banks to seek additional capital that negatively impacts a central bank’s operational and financial independence.

Accounting Policy Mismatches

Reporting in accordance with international standards, central banks account for the bulk of their liabilities at cost. This means that the value of these liabilities remains unchanged in the balance sheet even if their market value has shifted.

On the asset side however, central banks value some financial instruments at fair value and some at cost. This asymmetry between the way that central banks value their assets and their liabilities creates volatility in either the central banks’ reported profit and loss or their revaluation reserves.

Open Foreign Exchange Positions

The open FX position (highlighted in the schematic above) creates large exchange rate movement gains and losses that is a key source of balance sheet volatility.7

Reserve management policies present a further challenge. With a mandate to manage foreign currency reserves, reserve managers focus on maintaining the foreign currency value of those assets, rather than national currency revaluations. Given that central banks aim to hold reserves on a long-term basis, the general assumption is that revaluation gains will largely offset revaluation losses through an exchange rate cycle.

When revaluation losses accumulate, revaluation reserves, created from prior revaluation gains exist to provide a first level protection. They offset the inherent volatility within central bank balance sheets and ensure that central bank balance sheets are robust across business cycles.

As such, while most central banks recognise revaluation gains in their financial statements, they do not allocate them to statutory capital or distribute them to the government as dividends. The rationale behind this is clear:

The USD is the world’s pre-eminent reserve currency. Most central banks hold the majority of their FX reserves in USD and this exposes their equity to any volatility in the US currency.

One option is to find an asset that offsets gains and losses in the USD, rising in value as the value of the USD declines and thereby offsetting USD revaluation losses. Gold is one such asset.

Central banks collectively own more than 35,000 tonnes of gold and it is the third-largest reserve asset in the world.

When central banks revalue gold, they do so in their national currency. As such, the revaluation combines movements in the USD-denominated gold price and the USD/national currency exchange rate.8

As gold serves as a safe haven in times of financial strife, when the USD weakens, the flight to safe assets includes gold.

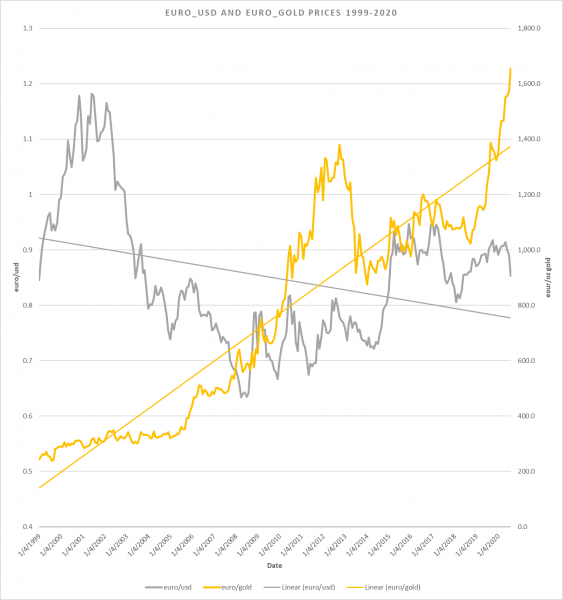

Simply put, when the USD falls, the gold price tends to rise creating a negative correlation between the price of gold and the USD exchange rate with the national currency. Given the USD’s reserve currency status, many factors impact this correlation. The relationship of the euro and the USD gold price illustrates this point. Figure I presents the combined effect of the price of gold in USD and the euro-USD exchange rate, from 1999 to the summer of 2020.

Figure I.

Source – MacroTrend Data Download/World Gold Council

The chart trendlines indicates that a negative correlation exists of -.303.9 As the euro itself is a reserve currency, this may, along with the wide range of factors, dilutes the hedging impact of holding gold in reserves for central banks whose national currency is the euro.10 Conversely, however, given that gold’s negative correlation characteristics are apparent even with the euro, the effect is likely to be even more pronounced for non-reserve currencies.

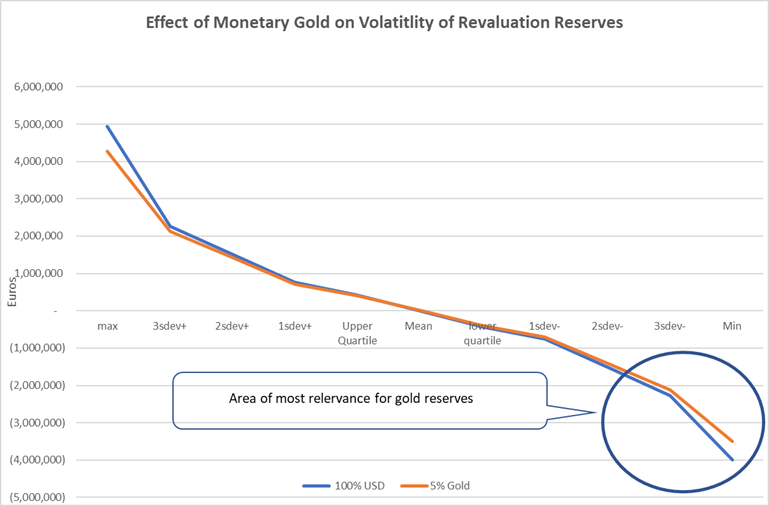

A detailed look at the relationship between the euro and gold shows that the negative correlation effect becomes more pronounced at times of crisis. Figure II models two hypothetical reserves portfolios with zero gold and 5% gold reported in euro.11

Figure II.

This indicates that holding gold is particularly useful at times of greatest market volatility when central bank balance sheets are most likely to come under stress.

Central banks’ balance sheets open FX positions contain unique stresses and strains that creates volatility. This can become acute during periods of market turmoil. Gold is a counter-cyclical asset that tends to rise in price when the USD falls. As the USD is the pre-eminent reserve currency, central banks that hold gold on their balance sheet benefit from its natural hedging properties. These properties are particularly relevant, because central banks convert the price of gold to their domestic currency when they revalue their reserves, so that the rising gold price partially offsets the USD weakness effect. The proportion of gold held will depend on central banks’ individual circumstances and policy direction. However, our analysis reveals that gold can make a positive contribution to the strength and stability of central banks’ revaluation reserves, especially in extreme situations, when central bank balance sheets are likely to be under the most significant stress.

This Policy Brief is based on the World Gold Council’s publication “Monetary Gold and Central Bank Capital” authored by Kenneth Sullivan, published on July 6, 2021.

It is relevant to all central banks with an interest in maintaining their equity, particularly emerging market central banks that hold USD against country USD liabilities. These central banks are responsible for managing their nation’s FX reserves and carry those reserves as assets on their balance sheet.

Unless stated otherwise, any reference to gold in the paper is to monetary gold.

Today, several central banks even offer negative interest rates to commercial banks.

The composition of central bank equity is beyond any international accounting standards or any commercial bank equity regulatory framework. Here, we adopt a framework of a split between realized statutory capital and unrealized revaluation reserves that summarizes their respective functions.

The strict nomenclature of these reserves is “unrealised revaluation reserves”. For simplicity, this paper describes them as “revaluation reserves” and makes a distinction only when the revaluation reserve refer to realised revaluation.

Two factors impact the volatility of the open FX position, the quantum of the open position and a currency mismatch between the denominations of FX assets and liabilities.

See the WGC papers on central bank accounting for gold at https://www.gold.org/what-we-do/official-institutions/accounting-monetary-gold

-ve1 would be a perfect negative correlation.

The paper chose the euro because four of the ten top central banks holding material amounts of gold are eurozone banks, Germany, Italy, France, and Netherlands.

This weighting is arbitrary and does not constitute, in any way, a recommended weighting of gold in a portfolio.