The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission or the European Fiscal Board. The column summarises a report prepared in the context of the 2024–2025 EU Fellowship Programme of the European Commission at the Institute for European Policymaking @ Bocconi University (IEP). Special thanks go to Daniel Gros, the Director of the IEP, for hosting me at the institute and for his supportive stance during my stay. I am grateful to a wide range of interlocutors from EU institutions, national authorities, academia, and think tanks who shared their insights and perspectives. While their contributions informed this work, all views expressed, and any remaining errors, are my own. The full report is available at BEER 47 -all.pdf.

Abstract

Mid-July, the European Commission fired the starting gun on the negotiations of the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) – the EU’s budget. Against an increasingly volatile geopolitical and economic backdrop, pressure is mounting to increase and future-proof Brussels’ public finances. However, not all EU member states are ready to allocate more money to the central level. This contribution shows why linking funds from the EU budget to national reform and investment projects could help overcome the current impasse. It outlines a middle way to the current ‘bipolar’ governance framework characterised by unenforceable ‘lifestyle advise’ under the European Semester on the one hand and crisis management on the other.

For decades, discussions about increasing the EU budget or issuing joint debt have been stymied by mistrust between member states. On one side are the fiscally more conservative countries and main net contributors who fear becoming de facto guarantors of others’ debt. On the other side are member states facing structural economic issues and a high government debt burden, which make them recipients of EU support during crises when financial markets tend to reassess sovereign risks in an abrupt manner.

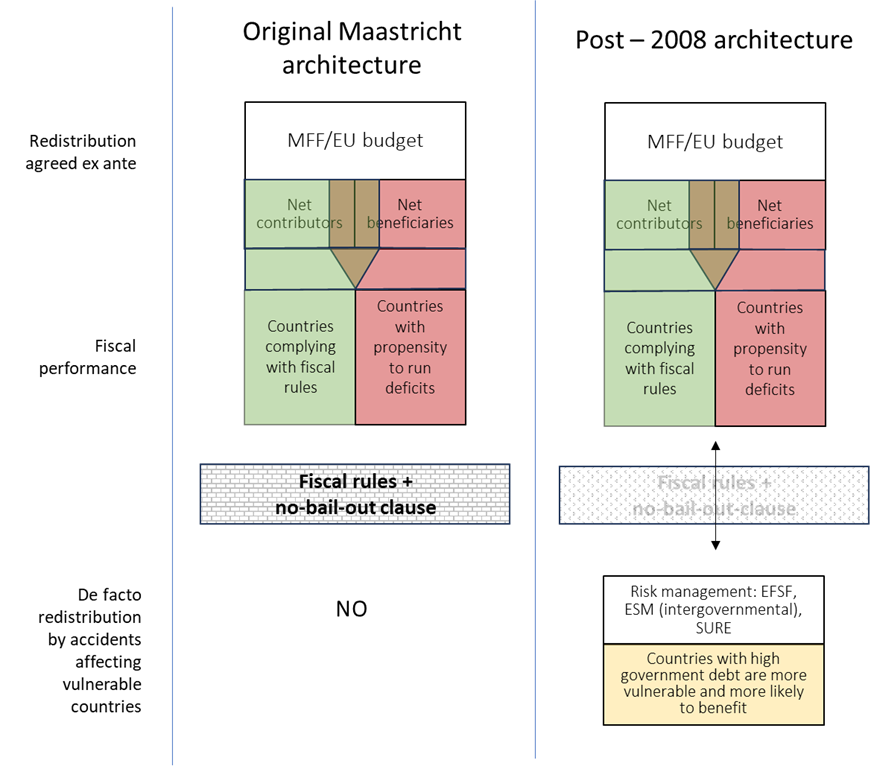

While the EU budget officially redistributes funds according to pre-agreed spending programmes based on EU laws (like agriculture, cohesion or regional development) a parallel process of accident-driven redistribution has surfaced: emergency support in the wake of large economic shocks. From the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to the SURE programme and the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), this system often ends up funnelling substantial amounts of money from the broadly same frugal countries to the same high-debt ones – despite the EU’s fiscal rules and no-bailout clause. The redistribution through the EU budget is fully controlled ex ante by the EU legislators through the normal budgetary process, the accident-driven redistribution is not and can be substantial.1

Figure 1. Types of redistribution in EU public finances

Note: Left – original design; right – current system combining planned redistribution via the EU’s regular budget with emergency transfer mechanisms after crises.

This dual-track redistribution has bred resentment and deepened divisions. ‘Frugal’ member states worry they are being asked to pay twice: first through the agreed, regular channel – the EU budget – and again when emergencies arise, and their hand is forced by the prospect of ‘disaster’ because the other group’s failure to follow the EU’s fiscal rules and the EU’s policy recommendations. At the same time, ‘less frugal’ member states insist they lack the tools to strengthen their economies in normal times and are left vulnerable when shocks hit.

At first glance, the solution might seem straightforward: enforce the set of commonly agreed fiscal rules more rigorously as per the original Maastricht design (see Figure 1, left-hand panel). The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), after all, was designed to ensure sound fiscal policy, and prevent unsustainable national borrowing, as a precondition for the smooth functioning of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). But history shows that rules alone do not guarantee discipline. Member states with high deficits/debt often have enough allies to block sanctions. And when a severe crisis erupts, even the most rule-abiding countries will ultimately agree to emergency aid, because the alternative is taken to be worse (see Figure 1, right-hand panel). As a result, the logic underpinning the no-bailout clause collapses when contagion looms (see Kirchsteiger and Larch, 2024). This leaves the EU stuck in an unfortunate bipolar cycle: structural problems go largely unaddressed during calm periods, only to trigger crisis-driven and painful responses when conditions deteriorate.

While calls for a larger, more flexible EU budget have grown louder, they continue to collide with deep-seated resistance, particularly from countries concerned about underwriting what they see as endless fiscal leniency in others. At the heart of this tension is the diverging propensity to run deficits across countries combined with a EU’s fragmented fiscal architecture: an uneasy coexistence of strict budget rules, a small central budget, and a web of ad hoc solutions created in response to crisis.

This is where the RRF approach or conditional budgeting comes in, a pragmatic compromise between two extremes.2 On one end is the EU’s traditional method of issuing non-binding policy recommendations that one senior official flippantly but aptly dubbed ‘lifestyle advice’. On the other end are adjustment or support programmes grudgingly agreed on the back of severe shocks. Conditional budgeting offers a middle ground: it links EU funds to concrete national reform and investment projects agreed ex ante. Countries get access to EU money not just by complying with proper accounting, but by demonstrating real progress on economic and structural goals.

This is precisely how the RRF, the EU’s temporary post-Covid recovery tool, works. Unlike most traditional EU funds, which, loosely speaking, reimburse eligible expenditure, RRF payments are disbursed when member states meet specific milestones and targets. The approach has given Brussels and the Council a stronger role in oversight, while also giving national governments clearer incentives to implement change.

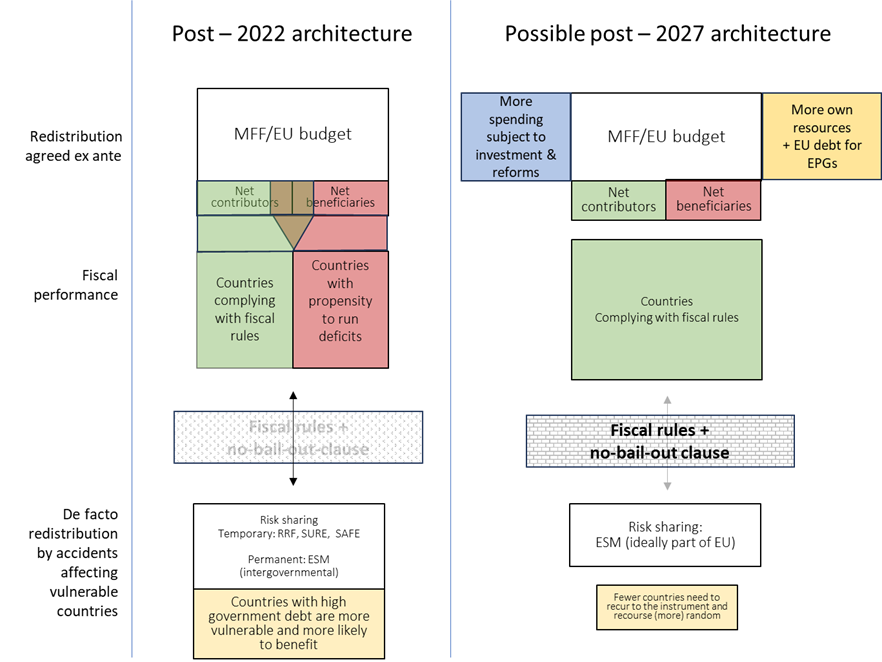

Conditional budgeting doesn’t just make economic sense. It offers a politically and economically viable bargain. Net contributors get assurances that their money supports reforms and investment rather than financing entrenched structures. Net beneficiaries gain resources that strengthen their long-term resilience, not just temporary lifelines when the house is on fire. In short, conditional budgeting can make a larger EU budget more palatable to those who pay the most into it (see Figure 2, right-hand panel). It transforms redistribution from an open-ended liability into a tool for shared prosperity. This could be the basis for a renewed political consensus, one that breaks out of the false dichotomy between fiscal union and fiscal discipline at the national level. The underlying idea can be conceptualised in a simple formal model.3

The Commission proposal of last July for the next MFF points into the right direction. It includes the idea of conditional budgeting by regrouping regional, cohesion and other money towards a system where member states commit to investment and reform projects under an integrated national plan, and payments are made upon delivery.

The crucial question is whether conditional budgeting actually works. Italy provides a promising case. As the single largest recipient of RRF funds – over €190 billion – Italy has faced intense scrutiny. Long plagued by slow growth, high debt, and institutional bottlenecks, the country’s RRF plan focuses on judicial reform, digitalisation, and modernising public administration. So far, the results are encouraging. Compared to 2019, the backlog of civil court cases more than three years old has dropped by over 90%; the average duration of a trial, albeit still elevated, has fallen markedly. Public procurement has also sped up significantly, with awarding times falling and project execution becoming more efficient.

Importantly, this progress is being tracked not just by EU institutions, but by other independent monitors such as Banca d’Italia and the PNRR Lab at Bocconi University, to mention but a few. Their findings suggest that conditional funding has catalysed reforms long considered politically impossible.4 True, challenges remain: some projects are delayed, and institutional inertia has not vanished. But the evidence so far suggests that conditionality can work as intended when designed properly and accompanied by political commitment.

The broader implications of conditional budgeting are significant. If expanded beyond the temporary RRF experience, conditional budgeting could:

It may also shift the tone of EU budget negotiations long dominated by national net balances and juste retour calculations. By focusing on common priorities and shared value, conditional budgeting could recast the EU budget as a collective investment platform, rather than a pure redistribution mechanism.

Figure 2. Conditional budgeting as a tool for reform

Note: The shift from crisis-driven transfers (left) to conditional budgeting (right), which links EU funding to national reform and investment projects can reduce both financial risks and political tensions. EPG=European Public Goods.

Of course, conditional budgeting is no silver bullet. It requires robust monitoring, clear reform plans, and strong political will. It must be paired with credible enforcement mechanisms and new resources – possibly through EU-level taxation or reallocation of national revenues.

But it can be a promising starting point, one grounded in existing practice. Most importantly, conditional budgeting can be the necessary counterpart to any future expansion of the EU budget. Not just because it builds accountability, but because it allows Europe to act together before the next crisis hits, rather than scrambling in the aftermath. In a world of accelerating change and renewed geopolitical risk, the EU can no longer afford a fiscal architecture that relies on improvisation and denial.

In 2024, Giuliano Amato, a former Italian prime minister and convinced European, remarked: “We cannot say we are more European than others when our debt is the obstacle for others to accept common solutions. To be more European with the money of others is something the others are not ready to accept.”5 The future of EU public finances may well hinge on acknowledging this uncomfortable truth. Conditional budgeting offers a way forward enabling member states to act collectively without ignoring the asymmetries that continue to challenge unity. It invites all sides to invest in a more resilient and competitive Europe on terms that are shared, earned, and ultimately, sustainable.

Divisions over joint EU borrowing are not new. As early as the 1970s and 1980s, the European Commission experimented with common debt instruments such as the Community Loan Mechanism and the New Community Instrument. These efforts ultimately failed to win lasting political support, notably when an attempt to establish a regular EU bond presence stumbled over the opposition of ‘frugal’ member states (see Spielberger et al. 2024).

The terminology around alternative forms of government budgeting is not set in stone. Following the OECD (2019), the literature often refers to performance budgeting, defined as the systematic use of performance information to inform budget decision. Performance budgeting can take a variety of forms including what the OECD calls direct performance budgeting, i.e. linking budget allocations directly to performance measures, an approach that according to the OECD (2019) is not applied in any of its members, but comes closest to the idea of conditional budgeting discussed in this contribution.

Building on Kirchsteiger and Larch (2024), the full report underpinning this column includes a formal model showing how conditional budgeting can help overcome the current impass (see the annex of BEER 47 -all.pdf).

The annual reports of the Banca d’Italia include detailed assessments of structural polcy issues including those relevant under the country’s RRF. The Bocconi University in Milan established a dedicated entity, the PNRR lab, that documents the implementation of the countries RRP.

A IEP@BU Webinar Series: The Future of the EU Institutions | IEP@BU on 25 March 2025.