S&P Global Ratings expects the next European Commission to continue to prioritize EU competitiveness and the digital and green transition, as well as defense, security and immigration issues. In this series of Policy Briefs we take a closer look at the issues of:

On the first point, the subject of this note, we believe that the European Commission could consider, among other factors, the recent increase in defense spending in its debt sustainability analysis. The longer longer-term question for the next European Commission will be whether to sanction countries that deviate from their fiscal adjustment plans. Even though compliance with the old fiscal framework was mixed at best, no member state was ever sanctioned. Finally, we believe that the European Commission will have two key options to finance its long long-term investment need: increase or reform the EU budget or initiate a new round of joint borrowing.

Generally speaking, we expect the next European Commission’s roadmap to borrow heavily from the 2024-2029 Strategic Agenda that the European Council adopted on June 28, 2024.

In particular, we expect that the next European Commission will continue prioritizing the EU’s competitiveness vis-à-vis other major countries like the U.S. and China. One key aspect of this will be the further integration of the single market in policy areas such as energy, finance, and telecommunications.

A more active and coordinated industrial policy could emerge, perhaps with a particular focus on emerging technologies, although there is no broad consensus among EU members on an EU-wide industrial policy. In this context, more flexible state aid rules could follow, likely benefiting larger companies in strategic sectors.

Other priorities in the European Council’s recent Strategic Agenda include the digital and green transition, largely backed by Next Generation EU funds and programs. The latter are likely to continue running in most member states, albeit at a slower pace than we anticipated at their inception in 2021, due to capacity constraints when it comes to building the related projects in many recipient countries. Each program’s policy milestones are unlikely to change by the deadline in 2026, as most of them have already been renegotiated to reflect higher prices in 2022 and remain in line with key EU policy objectives.

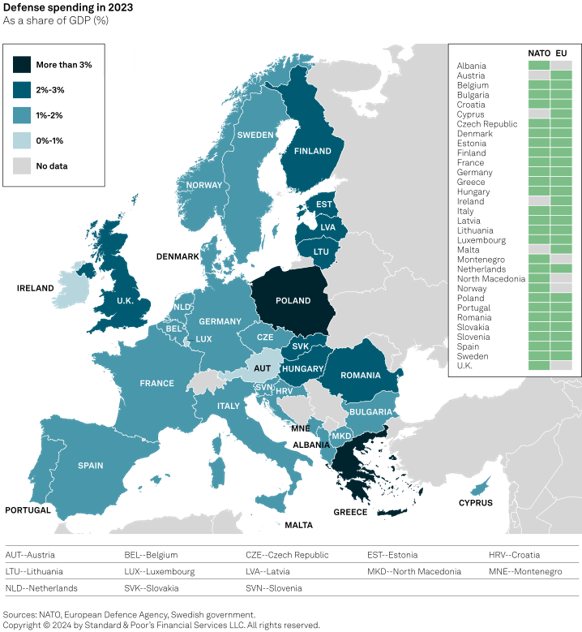

Additional areas of focus are defense, security, and immigration. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and lingering uncertainty over the U.S.’s long long-term commitment to NATO have put the onus on the European Commission to bolster the EU’s defense capacities. At the same time, the European Commission is likely to continue tackling EU voters’ growing concerns about immigration, as the EU and some recent national elections have brought to light.

The next European Commission will also have to address the EU’s enlargement, involving the delicate task of navigating accession talks with Ukraine and Moldova, as well as with other potential candidate countries. However, progress in this contested area might be slightly more difficult than during the last legislative period due to the greater polarization in the European Parliament following the elections.

The EU’s revised fiscal rules came into force in earlier this year. They had been suspended from 2020 to allow governments to deviate from the EU’s budgetary requirements to support their economies during the COVID-19 pandemic and energy price shocks.

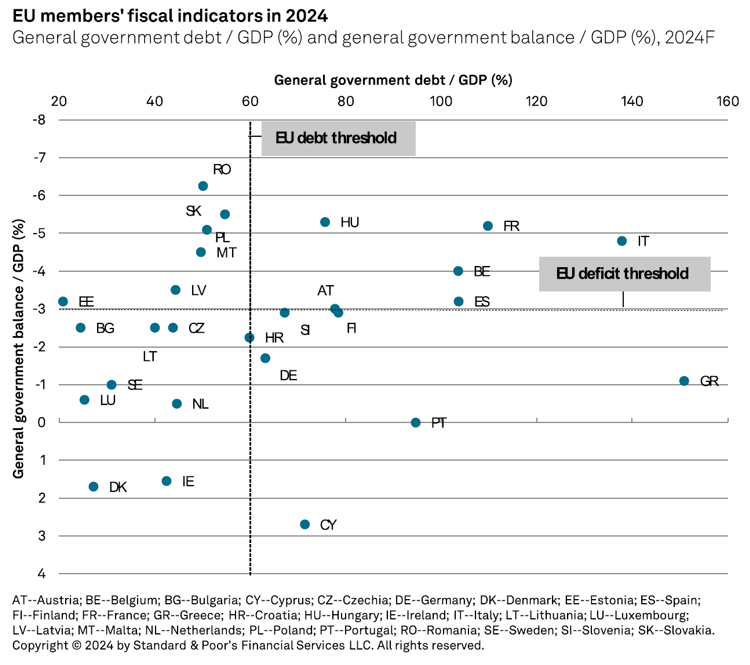

The new rules maintain the previous upper limits for government budget deficits at 3% of GDP and for government debt at 60% of GDP. Yet the new rules also offer somewhat more flexibility than before, meaning that:

The longer-term question for the next European Commission will be whether to sanction countries that deviate from their fiscal adjustment plans, with the new fiscal rules allowing a maximum fine of 0.05% of countries’ national GDP every six months until corrective action is taken. Due to concerns around member states’ fiscal sovereignty, enforceability has proved politically difficult in the past. Even though compliance with the old fiscal framework was mixed at best, no member state was ever sanctioned. This is because the European Council, which must sign off on a potential fine, was never aligned with the European Commission in such situations.

We generally think that the fiscal rules, and the possibility of an EDP that is activated when a country breaches the rules (see chart 2), can provide a fiscal policy anchor in member states, incentivizing them to comply with the agreed medium-term fiscal plans.

The European Commission has recently recommended or proposed initiating an EDP against several EU member states, namely, France, Italy, Belgium, Hungary, Malta, Poland, and Slovakia. In most cases, this is because these governments are in breach of the 3% GDP general government deficit threshold. The budgetary effort that these sovereigns will need to make will be clear after the release of European Council’s recommendations. These recommendations will reflect the European Commission’s assessment of the sovereigns’ 2025 draft budgets and the medium-term fiscal plans that they will deliver this coming autumn.

For eurozone members, being subject to an EDP means that their government debt securities could become ineligible for purchases under the European Central Bank (ECB’s) Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). This could increase their cost of funding in a hypothetical situation of financial fragmentation.

That said, our sovereign ratings will continue to focus on each individual country’s fiscal trajectory rather than on the EU’s thresholds and regulations. We think that fiscal performance ultimately depends on national economic factors and individual governments, including their ability and willingness to comply with the rules. That compliance may, in turn, rest on the capacity and stringency of the European Commission in tandem with the European Council in enforcing the rules.

Along with the need for fiscal consolidation, the bloc also faces the huge task of financing the green transition and digitization, as well as increasing defense spending to address geopolitical challenges. Most studies, as well as the European Commission’s official estimates, point to an investment gap north of €400 billion per year. This signals the need for additional financing at the consolidated EU level. In our view, this gives the European Commission two key options:

Increase or reform the EU budget

With the initial proposal for a new Multi-Annual Financial Framework due by mid-2025, the next European Commission will have to decide whether to propose an increase of the EU’s annual budget for 2028-2035 to further above 1% of the bloc’s gross national income. The European Commission could also recommend a reprioritization of expenditure by allocating a greater share to strategic sectors like defense or emerging technologies. EU subsidies could be made conditional on economic reforms, similar to the Next Generation EU program.

The European Commission’s longer-term budgetary challenge will be how to adapt the overall framework to the potential arrival of new member states whose level of economic development is substantially below the EU average. Regardless of the ultimate proposal, we expect the negotiations for the new Multi-Annual Financial Framework to remain challenging due to member states’ different priorities and the need for unanimity in the European Council.

Initiate a new round of joint borrowing

A second option would be to increase joint debt issuance to help finance climate, energy, or defense policy goals. The EU could issue debt directly, similar to the €750 billion Next Generation EU program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Alternatively, the European Investment Bank (EIB) could, with an enhanced role, finance such policy goals, as the European Council has already recommended in its Strategic Agenda.

Since the first disbursements from a new Multi-Annual Financial Framework would likely only start to flow from 2030, joint debt issuance would provide a speedier response to the bloc’s challenges. As was the case with Next Generation EU, a similar, albeit smaller, program would likely add upside potential to sovereigns’ short- to medium-term growth outlooks and increase temporary breathing space for highly indebted sovereigns.

However, recent delays in member states’ spending of Next Generation EU funds have also raised questions about the effectiveness of a new joint debt issuance program. The EIB estimates that only 44% of the milestones and targets set for the third quarter of 2023 have been met, leading some member states to call for an extension of the spending deadline beyond 2026.

Among European Council members, we not only anticipate vastly divergent views on the question of new joint EU debt, but also on the continuation of Next Generation EU, which fiscally conservative countries view critically. Our ‘AA+’ rating on the EU reflects our assessment of the ‘aa-‘ anchor, which is based on the weighted-average sovereign foreign currency ratings on the member states. The rating also reflects our view that the member states that we rate at least two notches above ‘AA-‘ are able and willing to cover any potential shortfall in the EU’s debt service.

Chart 1

Chart 2

Related Research from S&P Global Ratings

• CreditWeek: What Does The U.S.-Eurozone Interest Rate Differential Mean For Currencies And Capital Flows, June 20, 2024

• Supervising Cyber: How The ECB Stress Test Will Shape The Agenda, March 6, 2024

• EU Banking Package: Inconsistencies Temper Framework Improvements, Jan. 9, 2024

• Europe’s Power Push: Can Project Finance Help Fund Interconnections?, Nov. 16, 2023

• Thirty Years Of The EU Single Market: Why Cross-Border Capital Flows Remain Sluggish, Despite Positive Developments, May 25, 2023

• How the Capital Markets Union Can Help Europe Avoid A Liquidity Trap, April 15, 2021

• The EU Capital Markets Union Can Turn The Tide in Europe, Feb. 25, 2020