The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the institution the author is affiliated with.

Not all geopolitical shocks hit the economy in the same way – and that matters, especially for their transmission to inflation. Some shocks send oil prices soaring, while others push oil prices down. These price signals contain information on the transmission channels of geopolitical risk. By looking at how oil prices and geopolitical risk move together around major events, it is possible to identify different types of geopolitical shocks and assess their macroeconomic consequences. In a recent BdF Working Paper, I propose a novel methodology to disentangle geopolitical energy shocks, which are inflationary and contractionary, from demand-like geopolitical macro shocks, which slow down the economy and bring inflation down. Identifying which is which can make a big difference for central banks.

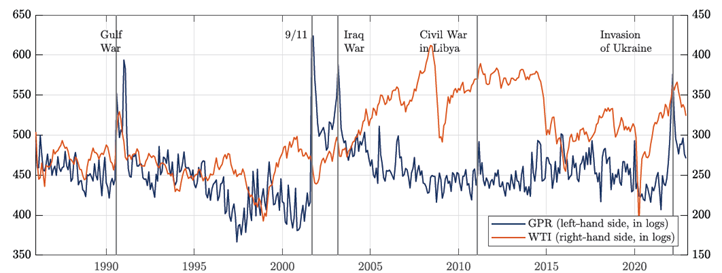

Are all geopolitical shocks alike? In a recent BdF Working Paper, I show that they are not. Figure 1 shows how geopolitical risk and oil prices have moved together – or not – from 1986 to 2022. The blue line tracks the Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR) by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022), while the red line shows oil prices (WTI). Some events, like the Gulf War or the Russian invasion of Ukraine, trigger supply disruptions in energy markets. Others, such as the 9/11 attacks or the more recent terrorist incidents in Europe, primarily affect broader macroeconomic sentiment, often leading to falling oil prices. This paper introduces a new way to tell different geopolitical shocks apart – by looking at how oil prices and geopolitical risk move together around major events. When both spike, it signals a geopolitical energy shock, typically driven by fears of supply disruptions. But when geopolitical risk rises while oil prices fall, it points to a geopolitical macro shock, reflecting broader concerns about the global economy rather than energy markets.

Figure 1. Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR) and Oil Prices (WTI)

Note: GPR = Geopolitical Risk Index (log), WTI = West Texas Intermediate oil price (log, deflated by CPI).

Source: Caldara and Iacoviello (2022), US EIA

Geopolitical shocks of different kind can be identified by looking at the comovements of the geopolitical risk index and oil prices around key geopolitical episodes. To do so, I construct a new dataset of three-day “surprise” responses of the geopolitical risk index and oil prices around 31 major geopolitical events since 1986. The idea is focusing on what happens at the geopolitical risk index and oil prices around major geopolitical events. When GPR and oil prices rise together, I interpret the event as a geopolitical energy shock. When GPR rises but oil prices fall, I interpret it as a geopolitical macro shock.

This comovement between oil prices and the geopolitical risk index is measured using a three-day window around key events – a technique inspired by high-frequency methods in monetary policy research. In particular, the paper builds on the approach developed by Jarociński and Karadi (2020), which uses short-term market reactions to disentangle overlapping shocks. By applying this framework to geopolitical events, the paper constructs a dataset of “surprises” –sudden shifts in risk and oil prices – and feeds it into a structural VAR model identified via narrative high-frequency sign restrictions.

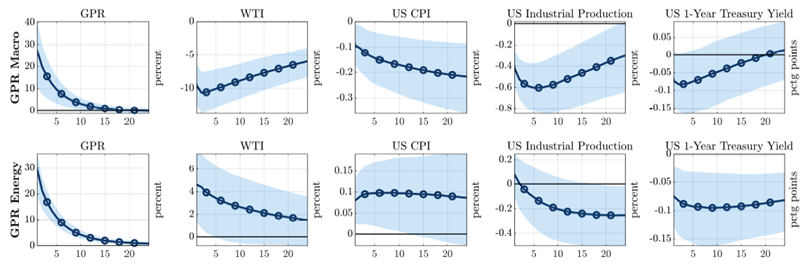

The effects of these shocks on the US economy differ in meaningful ways. As illustrated in Figure 2, while both shock types are contractionary for output, their effects on inflation diverge. Geopolitical energy shocks raise both geopolitical risk and oil prices. They act like adverse supply shocks, increasing production costs and consumer prices. In contrast, geopolitical macro shocks typically raise geopolitical risk but are associated with falling oil prices, reflecting demand-side concerns. Quantitatively, geopolitical energy shocks on average raise inflation by up to 0.2%, while macro shocks on average reduce it by 0.1–0.4%. This inflationary effect of energy shocks persists for several months and reflects their supply-side nature, similar to conventional oil price shocks.

Figure 2. Macroeconomic Effects of GPR Macro and Energy Shocks

Note: Responses to a one standard deviation GPR shock. Shaded areas represent the 68% credible set.

In the paper, I validate this classification using sectoral data on US manufacturing industries. The results confirm that energy-intensive sectors suffer more under geopolitical energy shocks. Their output contracts more sharply, and their prices rise significantly more than those of other sectors. For example, sectors such as basic metals and petroleum products are particularly vulnerable, with output declines reaching -3% and price increases exceeding 1% following energy-related shocks. These sector-level findings reinforce the view that energy channels are the dominant driver of inflationary pressure during major geopolitical episodes.

Geopolitical shocks do not always have the same kind of macro consequences. Their economic consequences hinge on their underlying nature. Identifying and responding to these differences is essential for effective policymaking –particularly in a world where geopolitical tensions are likely to remain high. Central banks should assess whether a geopolitical shock is primarily demand- or supply-driven. Our findings suggest that loosening policy may be appropriate in response to geopolitical macro shocks, whereas tightening may be required when energy markets are the primary transmission channel – though such decision must weigh inflation control against recession risks.