This policy brief is based on CESifo Working Paper No. 12246. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

Understanding the real and financial effects of monetary policy shocks remains a central – and contested – question in macroeconomics. These effects are often estimated with Vector Autoregressive (VAR) models, which require assumptions that separate endogenous policy responses from genuine monetary policy surprises. We show that combining two popular identification strategies – narrative restrictions and policy-rule restrictions – often seen as substitutes by academics and economists working in policy circles and think tanks, substantially improves our ability to recover credible monetary policy shocks, their effects on real and financial variables, and the Phillips multiplier.

The macroeconomic literature has long relied on Structural VARs (SVARs) to study how monetary policy affects inflation, real activity, and financial indicators. Identification is the key challenge: researchers must disentangle the central bank’s endogenous responses to economic conditions from true exogenous policy shocks.

A common approach, pioneered by Faust (1998), Canova and De Nicolò (2002), and Uhlig (2005), imposes sign restrictions on the dynamic responses of selected variables to uncover the (unrestricted) responses of other variables of interest – such as output or financial spreads. For a contractionary monetary policy shock, for example, the policy rate should rise while prices and liquidity should fall.

However, sign restrictions alone have proven insufficient for reliably identifying monetary policy shocks, particularly with respect to output responses (see Wolf 2020 and the literature therein). Two recent contributions aim to strengthen this approach:

In Castelnuovo, Pellegrino, and Særkjær (2025), we make a simple but powerful argument: Reliable identification of monetary policy shocks requires restricting both the shock and the monetary policy rule. In other words, narrative restrictions and policy-rule restrictions are complements, not substitutes. When using these restrictions jointly, we find that impulse responses are more correctly estimated, and that the estimation precision of statistics of interest, such as the Phillips multiplier, significantly increases.

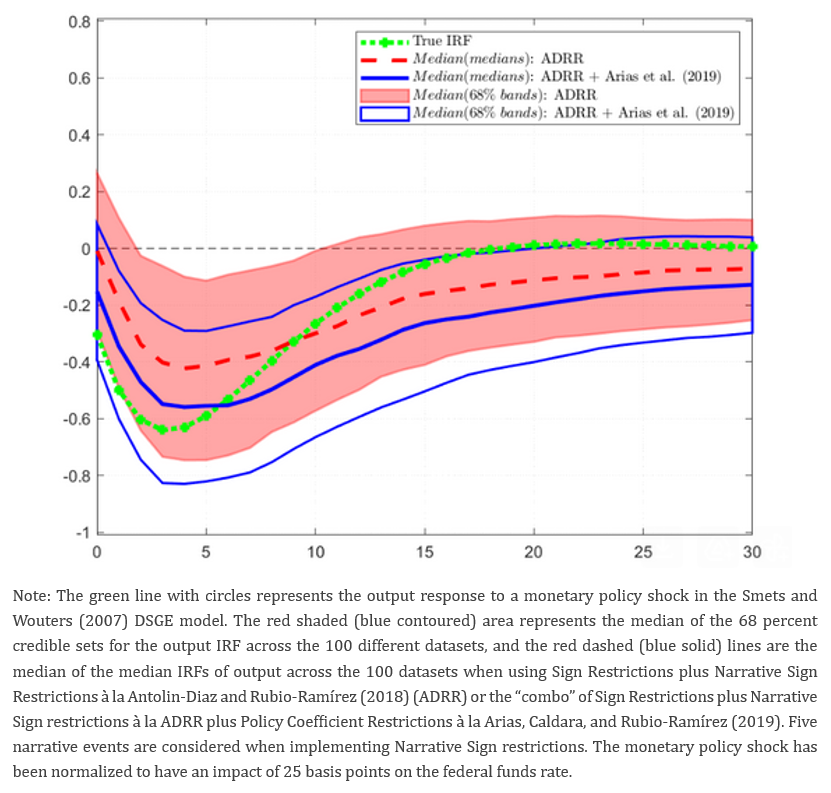

We demonstrate this insight through Monte Carlo experiments using the Smets–Wouters model as the data-generating process. Because the true impulse responses are known in simulations, empirical estimates can be evaluated directly. Our results show that augmenting narrative restrictions (NRs) with policy-coefficient restrictions (PCRs) markedly improves the estimated output response to a monetary policy shock. In the short to medium run, the “combo” (ADRR + Arias et al. (2019) produces impulse responses that lie much closer to the true model-implied dynamics than using narrative restrictions alone.

Figure 1. Monte Carlo simulations, response of real GDP to a monetary policy shock under different identification strategies

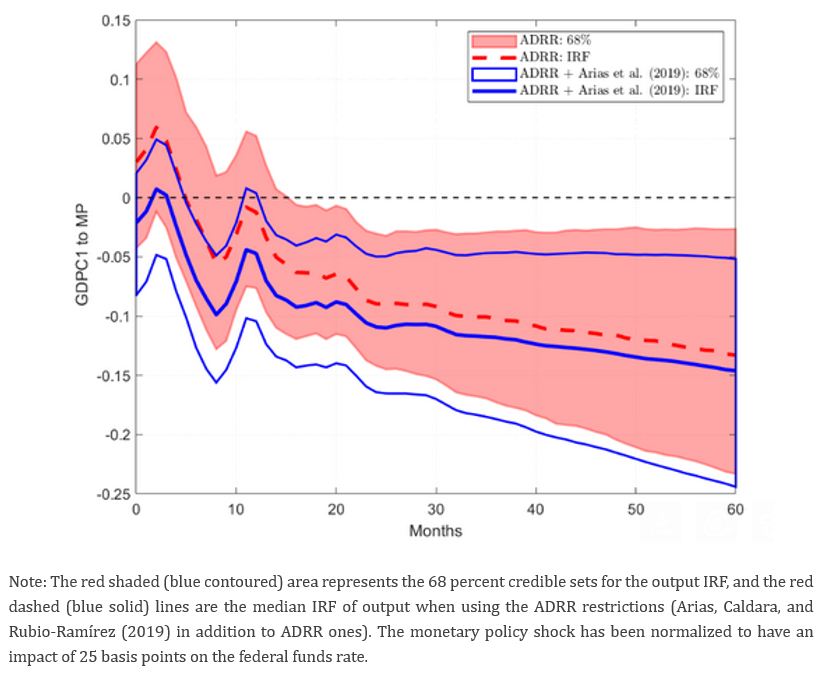

Using Uhlig’s (2005) original U.S. dataset, we replicate the exercise with actual data. Antolín-Díaz and Rubio-Ramírez’s narrative restrictions already improve the output response relative to Uhlig’s. Yet adding policy-coefficient restrictions further sharpens the short-run contractionary effect, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. US data, real GDP response to a monetary policy shock: Role of policy coefficient restrictions

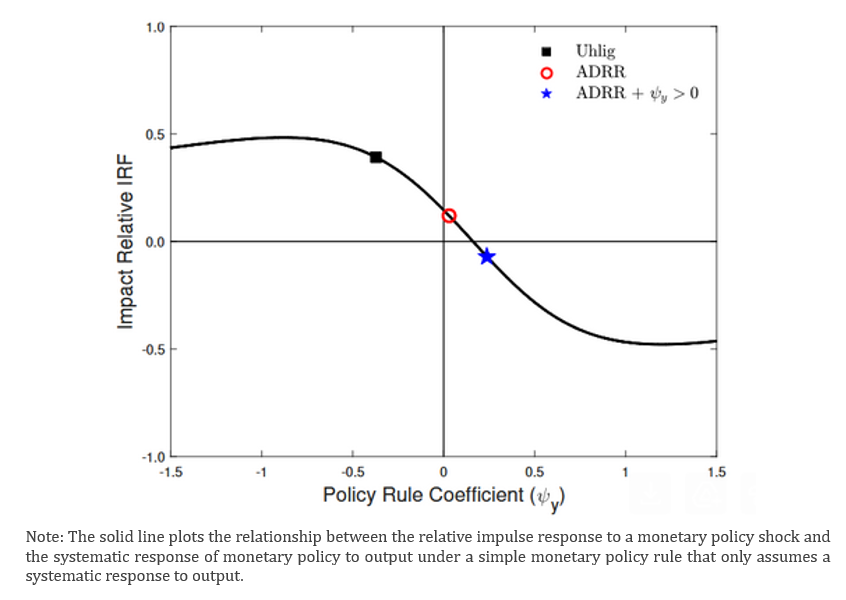

To understand why identification improves, we examine the implied systematic monetary policy rule. Interestingly, two patterns emerge:

We demonstrate that a simple analytical expression links the impact response of output to a monetary policy shock to the systematic component of the policy rule that regulates the policy response to output fluctuations. Figure 3 illustrates this mapping: a better-disciplined policy rule leads to a more reliable estimate of the real effects of a monetary policy shock.

Figure 3. Impact relative impulse response as a function of the systematic policy response to output captured by the policy coefficient ψy (simple monetary rule)

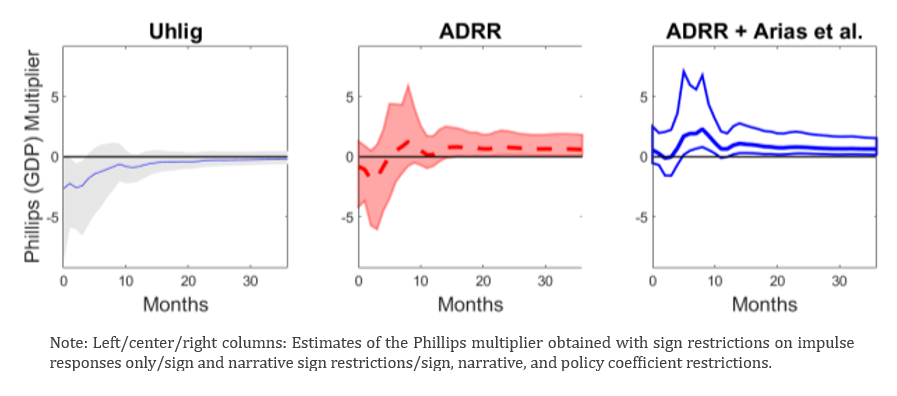

We also study implications for the Phillips multiplier – a central parameter for policy analysis recently investigated by Barnichon and Mesters (2021) that is correlated with the inflation-real activity trade-off faced by a monetary policymaker. Such a multiplier can be computed by combining the responses of inflation and industrial production to a monetary policy shock. Figure 4 shows that the combo not only stabilizes its estimate but also delivers narrower posterior bands, indicating higher precision.

Figure 4. Estimates of the Phillips multiplier across three different identification strategies

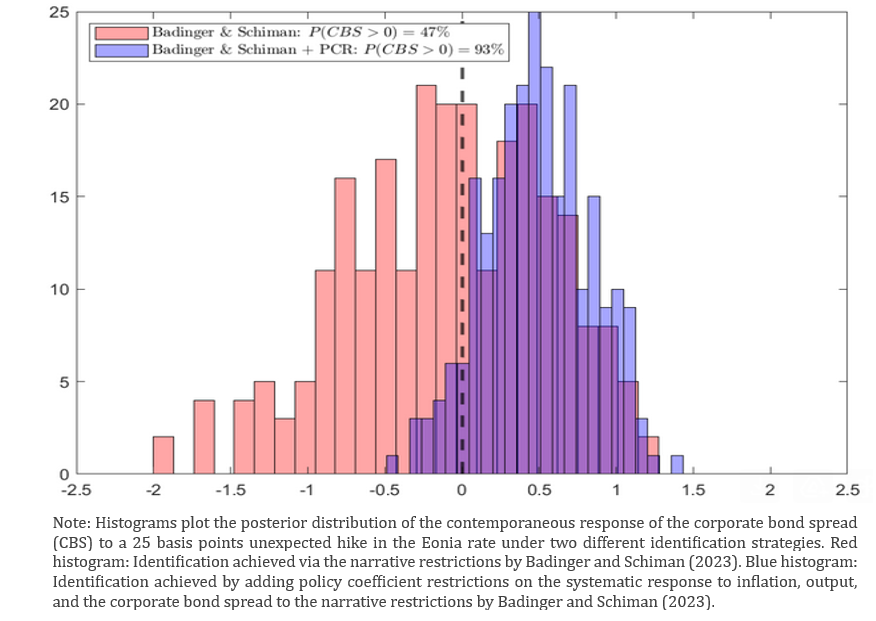

To assess whether our findings are U.S.-specific, we repeat the analysis with Euro area data, focusing on the corporate bond spread (CBS). Badinger and Schiman (2023), using narrative restrictions only, find an unexpected easing of credit conditions following a contractionary policy shock. Examining the implied systematic policy rule reveals why: the estimated ECB response includes the counterintuitive feature of raising the policy rate when credit conditions tighten. Imposing the correct sign on this policy coefficient overturns this artefact. As shown by Figure 5, with the combo in place, the distribution of CBS responses shifts toward the expected tightening following a monetary contraction.

Figure 5. Contemporaneous response of the corporate bond spread to a monetary policy shock: Role of policy coefficient restrictions

Our results carry two important messages. Empirically, researchers should jointly impose narrative and policy-rule restrictions to recover the most credible and informative macroeconomic impulse responses. From a theoretical standpoint, the improved empirical responses we obtain provide clearer and more precise targets for the calibration of models used in monetary policy and business-cycle analysis. From a policy standpoint, our evidence confirms policymakers’ ability to affect the real and financial cycles, as well as the presence of an inflation-real activity trade-off that has to be accounted for by a central bank when engineering unexpected monetary policy interventions.

Antolín-Díaz, J., and J. F. Rubio-Ramírez (2018): “Narrative Sign Restrictions,” American Economic Review, 108(10), 2802–2829.

Arias, J. E., D. Caldara, and J. Rubio-Ramírez (2019): “The Systematic Component of Monetary Policy in SVARs: An Agnostic Identification Procedure,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 101, 1–13.

Badinger, H., and S. Schiman (2023): “Measuring Monetary Policy in the Euro Area Using SVARs with Residual Restrictions,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 15(2), 279–305.

Barnichon, R., and G. Mesters (2021): “The Phillips multiplier,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 117, 689–705.

Castelnuovo, E., G. Pellegrino, and L. L. Særkjær (2025), “Monetary Policy Shocks and Narrative Restrictions: Rules Matter”, University of Padova, Department of Economics and Management “M. Fanno” Working Paper No. 328-2025.

Canova, F., and G. de Nicoló (2002): “Monetary Disturbances Matter for Business Fluctuations in the G-7,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 49, 1131–1159.

Faust, J. (1998): “The robustness of identified VAR conclusions about money,” Carnegie Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 49, 207–244.

Smets, F., and R. Wouters (2007): “Shocks and Frictions in US Business Cycle: A Bayesian DSGE Approach,” American Economic Review, 97(3), 586–606.

Uhlig, H. (2005): “What Are the Effects of Monetary Policy? Results from an Agnostic Identification Procedure,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 52, 381–419.

Wolf, C. K. (2020): “SVAR (Mis-)Identification and the Real Effects of Monetary Policy,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 12(4), 1–32.