This policy brief is based on the paper „Monetary policy, central bank information, and bank lending: Evidence from German banks“, Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper (No 06/2025). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Deutsche Bundesbank.

Abstract

The possible presence of information effects of monetary policy raises the following questions: First, how do monetary policy shocks stripped of information about economic funda-mentals affect bank lending? Second, does non-monetary central bank information have autonomous effects on bank lending? We show that a conventional increase in the policy rate results in a significant reduction in bank loans to non-financial corporations, with the effect being more pronounced for smaller banks with less liquid balance sheets. Moreover, our analysis demonstrates that a policy rate hike driven by an information shock leads to a significant rise in non-financial business loans, with the increase being more substantial for smaller banks with more liquid balance sheets.

Banks are crucial in transmitting monetary policy. There is long-standing evidence that monetary policy affects bank loan supply and the real economy through a bank-lending channel. Yet, when central banks announce a policy rate decision, they also reveal information about their assessment of economic conditions. Recent studies show that the non-monetary information contained in monetary policy announcements has macroeconomic implications that are distinct from the conventional effects of monetary policy. Evidence shows, for instance, that the announcement of a rate hike may reflect good news about the economy, stimulating economic activity. Moreover, existing theoretical work shows that such information effects occur particularly when the announcement contains good news about the state of financial conditions. This raises the question, how bank lending reacts to both the monetary as well as the non-monetary component of central banks’ announcements.

In our study (List and Metiu, 2025) we add to research on the bank-lending channel of monetary policy transmission by considering the role of central bank information effects. We examine how bank lending to non-financial corporations (NFCs) reacts to central bank information shocks (CBI shocks) and to “pure” monetary policy shocks, i.e., those stripped of information effects (PMP shocks) identified as in Jarociński and Karádi (2020). Germany’s bank-dominated financial system makes it ideal for this analysis.

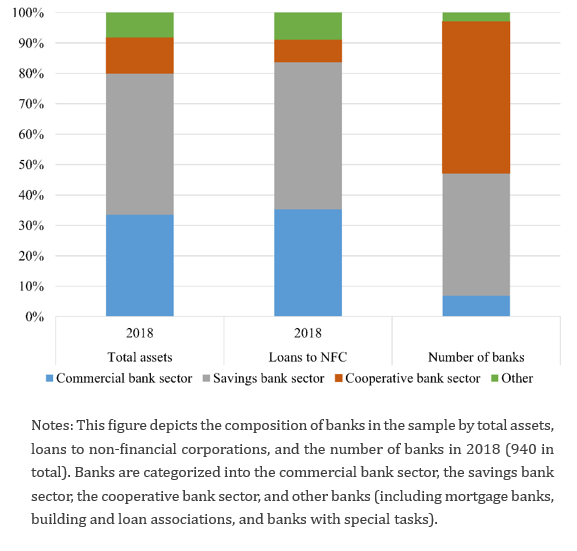

We use a confidential bank-level panel data set that contains quarterly information on German bank balance sheets for the period between 2002 and 2018. The data are collected by the Deutsche Bundesbank and comprise all NFC loans larger than 1.5 million euros extended by banks domiciled in Germany, along with additional balance sheet figures. After adjustments, our sample comprises a balanced panel of over 900 commercial, savings, and cooperative banks that account for nearly 70% of total banking system assets in 2018.

Figure 1. Composition of banks in the sample, 2018

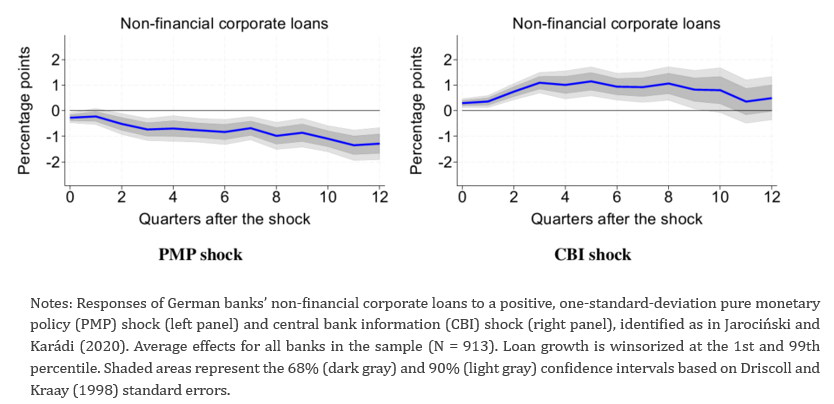

Using bank-level panel local projections (Jordá, 2005), we find that a positive PMP shock – i.e., an unexpected monetary policy rate tightening that is independent of information about economic fundamentals – leads to a statistically significant reduction in the volume of bank loans to NFCs. The effect is economically meaningful: On average across all banks, the loan volume decreases by around three-quarters of a percentage point one year after a one-standard-deviation positive PMP shock. The effects are relatively persistent, as firms receive nearly one and a half percentage points less credit relative to the pre-shock level three years after the shock.

The negative effects of a restrictive monetary policy shock on bank loans can be attributed to several mechanisms. Firstly, policy rate tightening reduces banks’ cash flows and increases indirect costs, negatively impacting the supply of new loans. Additionally, it lowers banks’ net worth by affecting the market value of their assets more than their liabilities due to maturity transformation, potentially further reducing loan supply (Boivin et al., 2010; Ciccarelli et al., 2015). Higher policy rates may also decrease firms’ loan demand by raising borrowing costs (Bernanke and Gertler, 1995; Ciccarelli et al., 2015).

At the same time, we find that a positive CBI shock – i.e., an unexpected policy rate tightening that reflects non-monetary information about economic fundamentals – leads to a statistically significant increase in the volume of loans extended to non-financial firms. On average across all banks, the loan volume rises by more than one percentage point one year after a one-standard-deviation positive CBI shock.

Our results complement recent evidence that news about economic fundamentals are an important component of monetary policy surprises (Jarociński and Karádi, 2020; Andrade and Ferroni, 2021; Miranda-Agrippino and Ricco, 2021). Existing studies adopt the idea of a “central bank information” effect, whereby investors’ beliefs about the state of the economy adjust in response to the central bank’s announcement (Jarociński and Karádi, 2020).

Figure 2. Impulse responses for all banks

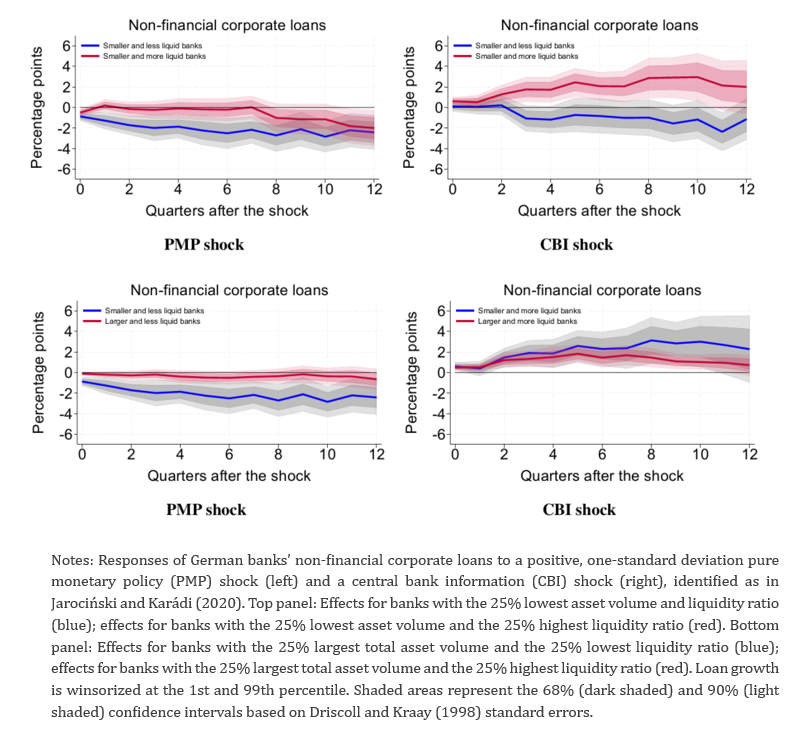

We examine separately banks that differ in balance sheet characteristics that mainly influence the supply of credit (Kashyap and Stein, 1995, 2000). Specifically, we group banks by the size and liquidity position of their balance sheets.

The results show that the decline in loans after a PMP shock is stronger for relatively small banks with less liquid balance sheets, Hence, relatively small banks that have worse access to external finance are more responsive to PMP shocks than larger banks, consistent with a bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission.

Moreover, we find that the increase after a positive CBI shock is stronger for relatively small banks with more liquid balance sheets. Thus, when a policy rate tightening conveys good news about economic fundamentals, smaller and more liquid banks use their extra liquidity to expand business lending. This result adds a new dimension to the role of banks in the transmission of central bank policy. There are at least two potential explanations for why relatively small banks might be more affected by a CBI shock. First, smaller banks might face more information asymmetries because they have fewer resources to monitor economic conditions than larger banks (Holod and Peek, 2007). The information shock is thus likely to have a higher novelty value for relatively small banks. Second, smaller banks might be more collateral-constrained than larger banks. The rise in collateral values after a positive CBI shock may thus primarily improve financing conditions for relatively small banks, allowing them to extend more loans. Our results are robust to how we measure exogenous variation in monetary policy and central bank information, as well as to various choices of measurement, sample composition, statistical inference, and model specification.

Figure 3. Impulse responses for smaller vs. larger banks grouped by liquidity

We obtain two main results: First, a conventional policy rate tightening significantly reduces bank loans to non-financial corporations, especially for smaller banks with less liquid balance sheets that are likely to have more difficulties with raising external funding. Second, a policy rate tightening due to an information shock significantly increases lending to NFCs, particularly by smaller banks with more liquid balance sheets that can use the extra liquidity for corporate loans. This supports theoretical work suggesting that central bank information shocks reflect news about financial conditions.

Andrade, P., Ferroni, F., 2021. Delphic and odyssean monetary policy shocks: Evidence from the euro area. Journal of Monetary Economics 117, 816–832.

Bernanke, B.S., Gertler, M., 1995. Inside the black box: The credit channel of monetary policy transmission. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, 27–48.

Boivin, J., Kiley, M.T., Mishkin, F.S., 2010. Chapter 8 – how has the monetary transmission mechanism evolved over time?, Volume 3 of Handbook of Monetary Economics, pp. 369– 422.

Ciccarelli, M., Maddaloni, A., Peydro, J.L., 2015. Trusting the bankers: A new look at the credit channel of monetary policy. Review of Economic Dynamics 18, 979–1002.

Driscoll, J.C., Kraay, A.C., 1998. Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially de-pendent panel data. The Review of Economics and Statistics 80, 549–560.

Holod, D., Peek, J., 2007. Asymmetric information and liquidity constraints: A new test. Journal of Banking and Finance 31, 2425–2451.

Jarociński, M., Karádi, P., 2020. Deconstructing monetary policy surprises: The role of information shocks. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 12, 1–43.

Jordá, O., 2005. Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review 95(1), 161–182.

List, S., Metiu, N., 2025. Monetary policy, central bank information, and bank lending: Evidence from German banks. Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper 06/2025.

Kashyap, A.K., Stein, J.C., 1995. The impact of monetary policy on bank balance sheets. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 42, 151–195.

Kashyap, A.K., Stein, J.C., 2000. What do a million observations on banks say about the transmission of monetary policy? American Economic Review 90, 407–428.

Miranda-Agrippino, S., Ricco, G., 2021. The transmission of monetary policy shocks. Ameri-can Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 13, 74–107.