This policy brief is based on BIS Working Paper, No 1246. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS, the Bank of England or its committees.

Abstract

There is mounting evidence suggesting that monetary policy can influence long-term real interest rates, though the underlying mechanisms driving this outcome remain unclear. We argue that this occurs because very persistent policy-induced interest rate changes may have only weak effects on economic activity. This can happen when consumption-savings decisions are not solely driven by intertemporal substitution but also by life-cycle forces associated with retirement savings. In this context, we show that the impact of highly persistent monetary policy shocks on economic activity is shaped by two key forces: an asset valuation effect and the response of the average marginal propensity to consume out of financial wealth. Our quantitative analysis indicates that these forces likely offset each other, effectively allowing monetary policy to (unintentionally) drive trends in long-run real rates. Our findings suggest that very precise knowledge of the natural rate of interest, r*, may not be essential for the successful conduct of monetary policy.

The standard New Keynesian model suggests that long-term real rates must closely track the natural rate of interest, r*, to prevent inflation from spiralling out of control. In this framework, central banks are merely “followers” of long-term real trends in interest rates rather than active drivers.

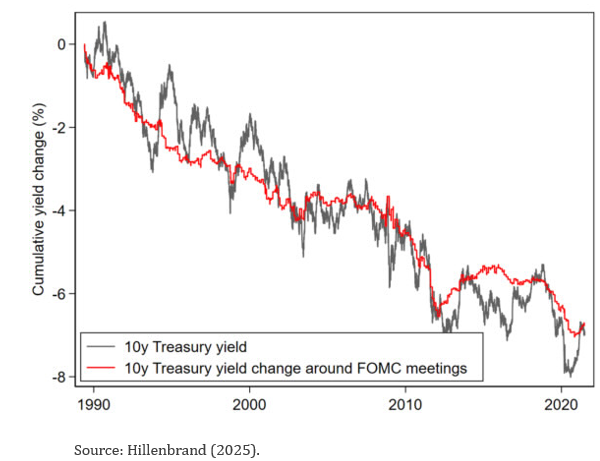

Given this perspective, it is surprising that the data show long-term real interest rates to be highly responsive to monetary policy decisions. Most notably, the entire observed decline in long-term interest rates since the 1980s has occurred in a narrow 3-day window around FOMC meetings (Hillenbrand, 2025); see Chart 1.

Chart 1. Entire observed decline in long-term interest rates (black line) has occurred in a narrow 3-day window around FOMC meetings (red line)

One possible explanation for the observation in Chart 1is the so-called “Fed information effect”, where the central bank, through its actions and communications during FOMC meetings, reveals its superior knowledge about underlying real trends. However, in a world where the private sector has access to much of the same (if not more) data, models, and expertise, this explanation appears difficult to justify.

An alternative and more direct explanation is that central banks may simply have the ability to influence real rates over much longer periods than is traditionally believed. However, this perspective raises an important question: how is it possible that persistent deviations of interest rates from r* do not lead to large deviations of inflation from the central bank’s target?

In our paper (Beaudry, Cavallino, and Willems, 2025), we argue that to understand the effects of very persistent changes in interest rates on economic activity it is essential to examine their impact on both the demand for assets and their valuation. Specifically, we argue that retirement-related saving incentives give rise to a “persistence-potency trade-off”. In our framework, the effectiveness of interest rate changes diminishes as their persistence increases. This trade-off allows monetary policy to sustain low interest rates over extended periods without generating significant excess demand. In such a scenario, even if central banks are unaware of this dynamic, they may unintentionally become key drivers of secular trends in long-term real interest rates.

To formally analyse the effects persistent deviations of the real interest rate from r*, we develop a Finitely-Lived Agent New Keynesian (FLANK) model. This model incorporates life-cycle dynamics that distinguish between workers and retirees, providing a rich yet concise framework to describe the relationship between the path of future interest rates and economic activity.

A key insight from our model is that the effects of highly persistent monetary policy shocks can be distilled into two simple effects. First, there is a standard valuation effect for assets with positive duration, which operates in the conventional direction (ie, with higher rates lowering aggregate demand and vice versa). Second, there is an effect on the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of financial wealth, which tends to work in the unconventional direction. The net result is that persistent interest rate changes may have little impact on excess demand.

To understand this, consider a retired household or one saving for future retirement. It is not obvious that such households would increase consumption in response to capital gains resulting from persistently lower interest rates. This is because the typical household is “short duration,” meaning their prospective labour income stream has a shorter duration than their prospective consumption stream (due to the retirement phase). When rates fall, the present value of household liabilities may increase by more than the present value of their assets. This dynamic incentivizes households to hold more assets to compensate for the lower yield on each unit, rather than increasing consumption. This “interest income effect” implies that the aggregate MPC out of financial wealth may decrease when interest rates fall persistently. This effect works in the unconventional direction, with lower rates dampening demand. Meanwhile, the asset valuation effect works in the conventional direction, creating opposing forces that may largely offset each other. For reasonable calibrations, out findings indicate that these effects can indeed cancel out, implying that persistent rate changes have a rather limited impact on excess demand.

When the persistent component of monetary policy has limited effects on demand, interest rates can deviate from r* “for long” without significant impact on inflation. Consequently, if central banks misperceive r* and use this misperceived estimate to guide policy, they will receive very few signals indicating their error. In other words, the system becomes quite “forgiving” of a central bank that sets policy based on an incorrect view of r*. This can result in central banks unintentionally driving real interest rates over extended periods of time without realizing it. For instance, a rate cut initially intended to be temporary could gain persistence if it leads the central bank to erroneously lower its estimate of r*. Similarly, a rate hike could induce the opposite effect. In such an environment, it becomes rational for markets to view central bank decisions and statements as influential for long-term rates, even if they do not believe central banks possess private information about r*.

Our model can also be applied to other questions related to monetary policy. For example, our framework predicts that conventional monetary policy – conducted by adjusting the policy rate – becomes less potent in a post-QE world. This is because quantitative easing (QE) shortens the duration of assets held by the private sector, weakening the asset valuation effect which operates in the conventional direction. A similar conclusion applies to aging if it lengthens the average retirement period relative to the average working career. Such a development increases the importance of interest income in household finances, amplifying the unconventional effect where lower rates dampen demand.

Beaudry, Paul, Paolo Cavallino, and Tim Willems (2025), “Monetary policy along the yield curve: why can central banks affect long-term real rates?”, BIS Working Paper No. 1246.

Hillenbrand, Sebastian (2025), “The Fed and the secular decline in interest rates”, Review of Financial Studies, 38 (4).