This policy brief is based on Flaccadoro and Villa (2025), available as Bank of Italy Working Paper Series (1493). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Italy.

Abstract

We analyse the impact of shocks to global risk aversion on the term structure of sovereign spreads between emerging market economies (EMEs) and the United States (US). Focusing on the difference between long- and short-term spreads (i.e. the term premium gap), we find that an increase in global risk aversion reduces the term premium gap. This finding is consistent with the evidence that during crises EMEs experience a higher risk of default with respect to the US, and to a greater extent at shorter maturities.

Sovereign bond spreads between emerging market economies (EMEs) and the United States (US) are a key gauge of EMEs’ external financing conditions, as these countries rely heavily on foreign-currency bond issuance, mainly in US Dollar (USD). Understanding what drives these spreads is therefore crucial for policymakers concerned with financial stability and borrowing costs. While early research emphasized domestic “pull factors” (i.e. fundamentals) as the main determinants of spreads, more recent works have highlighted the influence of global “push factors,” such as world interest rates and international investors’ risk aversion (Uribe and Yue, 2006). Yet, despite broad recognition of the importance of risk aversion, little is known about how it affects spreads along the whole term structure of sovereign debt.

Our study addresses this gap by examining how exogenous changes in global risk aversion—defined as shifts in investors’ willingness to bear risk—affect the difference between long- and short-term EME sovereign spreads, which we label the term premium gap. The research question is whether global risk aversion shocks have heterogeneous effects across maturities, thereby altering the relative cost of long- versus short-term borrowing for EMEs in comparison with the US economy.

We find that it is indeed the case. In response to an exogenous increase in global risk aversion, yields rise in EMEs while they fall or remain broadly stable in the US due to flight to safety, hence widening the spreads. This effect is stronger at shorter maturities—as the perceived riskiness of EMEs increases more sharply at short maturities in comparison with the US economy—thus inducing a reduction in the term premium gap.

Our study isolates a default risk channel mechanism, shedding light on how risk-off episodes shape investor demand for EMEs sovereign bonds. In addition, by focusing on USD-denominated debt, the analysis abstracts from any effect stemming from the exchange rate dynamics. We conduct the study using a panel local projection framework to trace the dynamic responses of yields, spreads, and the term premium gap to risk aversion shocks, controlling for other global and country-specific factors.

Finally, we complement the baseline analysis with an alternative approach, by using Credit Default Swaps (CDS) connected to EMEs and US sovereign debt issued in USD. We show that an adverse global risk aversion shock increases the difference between CDS connected to EMEs bonds and those pertaining to US Treasuries, and more strongly so at shorter maturities, consistently with the default risk channel.

Our analysis relies on a daily panel dataset covering the period from June 1998 to October 2020 for five EMEs—Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, South Korea, and Turkey— and the US. We use zero-coupon sovereign bond yields denominated in USD. Yield curves are estimated using the Diebold and Li (2006) methodology, providing a consistent set of maturities across countries. From these curves, we construct three daily financial metrics for each emerging market: yields across a wide set of maturities; sovereign spreads relative to the US, measured as the difference between emerging market and US yields for the same maturity; and the term premium gap, which is defined as the difference between long- and short-term spreads. The term premium gap captures the excess cost EMEs pay to borrow at longer maturities compared to the safe US benchmark, and it is an indirect measure of the duration risk spread between EMEs and the US.

To capture investors’ attitudes toward risk, we construct a US-based proxy for global risk aversion following Bekaert et al. (2013). The method decomposes the squared VIX index into two components: (i) the expected physical variance of S&P 500 returns,which reflects market expectations of future realized volatility (i.e. the “quantity” of risk); and (ii) a time-varying proxy for risk aversion, measuring the compensation investors demand for bearing volatility risk (i.e. the “price” of risk).1

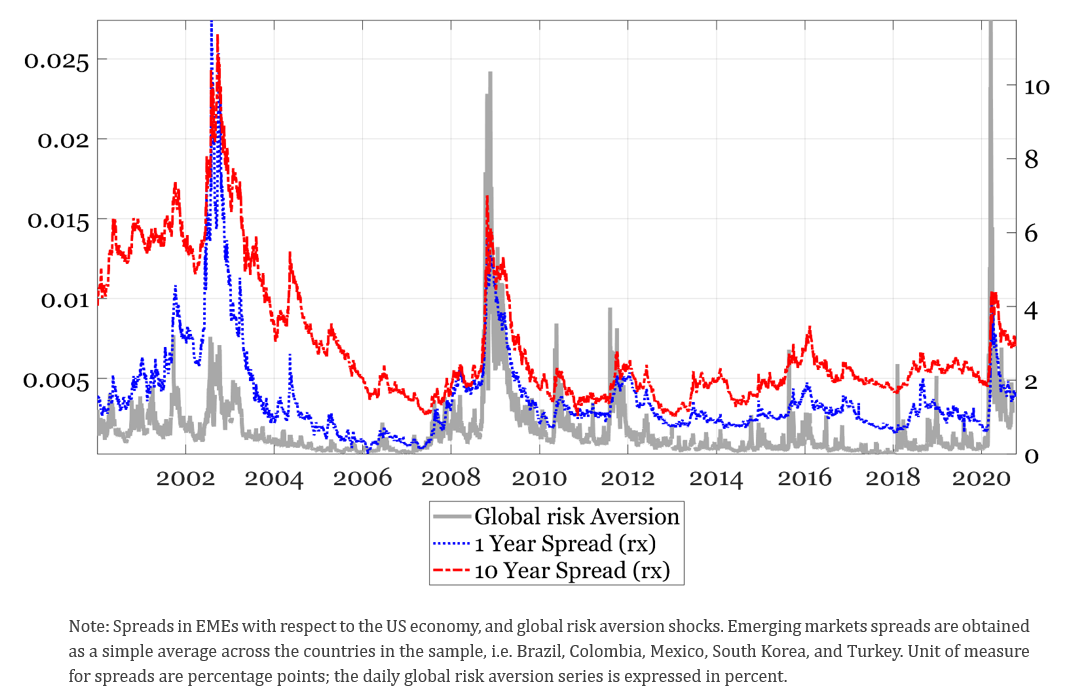

This measure of risk aversion rises sharply during well-known episodes of financial turmoil—such as the 2002 market downturn, the Global Financial Crisis, the European debt crisis, and the COVID-19 shock—thus providing a reliable indicator of investors’ changing risk tolerance (Figure 1). During such episodes, EMEs spreads increase at all maturities, but more strongly so at the short-term ones.

Figure 1. Global risk aversion and spreads in emerging market economies

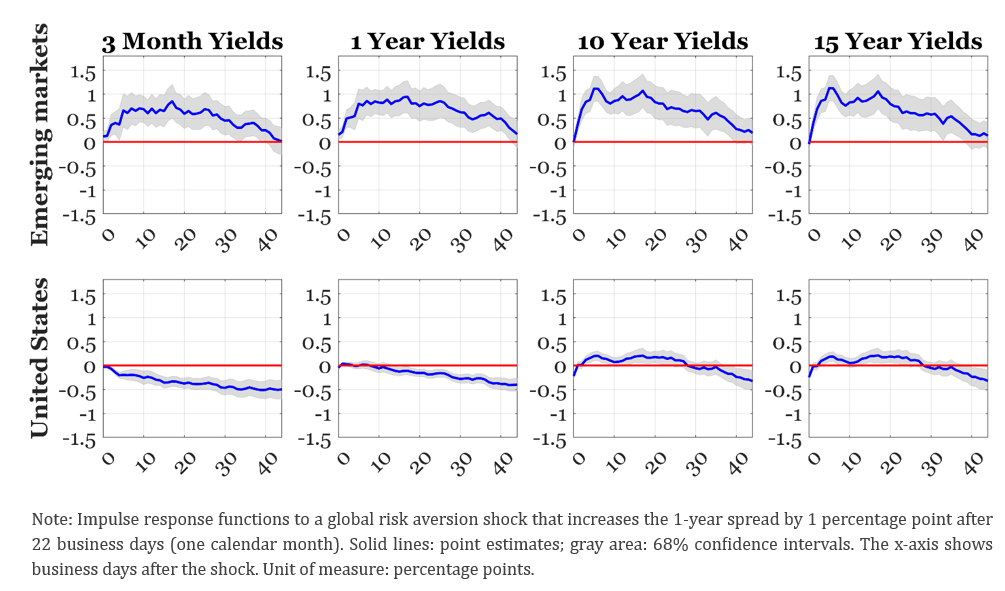

Before turning to EME-specific sovereign financial variables, we verify that our global risk aversion shock induces responses in other variables that are in line with economic intuition. An exogenous rise in risk aversion increases the VIX and appreciates safe-haven currencies such as the US dollar, the Japanese yen and the Swiss franc, while depreciating riskier ones like the British pound. This pattern confirms that the identified shock captures genuine “flight-to-safety” dynamics. Focusing on sovereign yields, we find that an adverse risk aversion shock significantly raises EMEs yields across the whole term structure while it decreases US yields, especially at shorter maturities (Figure 2). In simpler terms, the EMEs yield curve shifts upward almost in parallel, whereas the US curve rotates downward at the short end, consistent with investors’ rebalancing toward US short-term safe assets during risk-off episodes. Correspondingly, spreads between EMEs and US yields widen, particularly at short maturities, reflecting both higher perceived EMEs risk and lower returns on US Treasuries at short maturities.

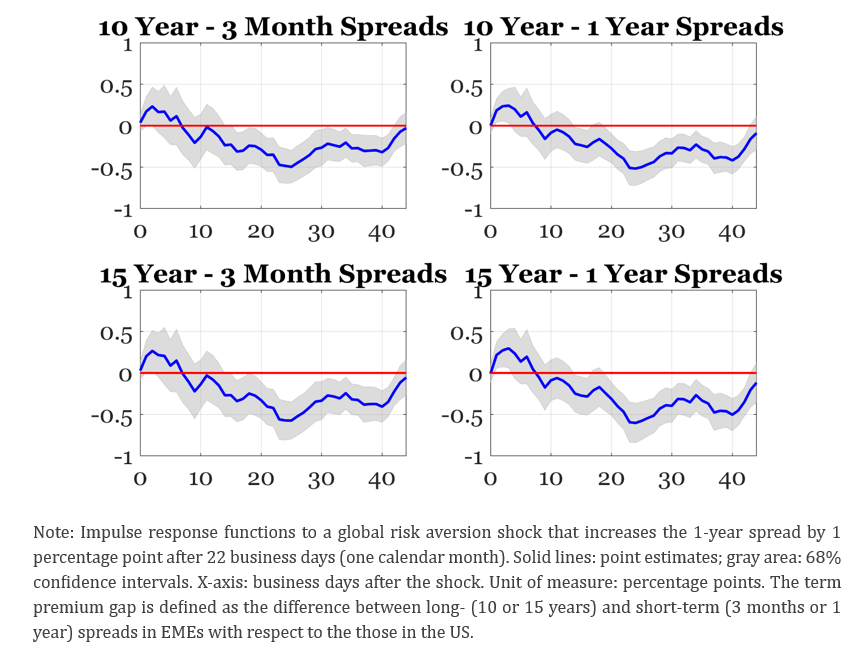

Finally, we focus on the term premium gap, defined as the difference between long- and short-term EMEs spreads relative to the US. In response to global risk aversion shocks, this measure declines significantly (Figure 3). The result is driven by the stronger rise in short-term spreads compared to long-term ones, consistently with a default risk channel: during periods of financial stress, investors perceive a higher probability of short-term EMEs default, while long-term risk remains relatively less affected. Complementary evidence from CDS confirms that perceived EMEs riskiness increases more sharply at short maturities in comparison with the US economy—where, instead, this default indicators barely move—reinforcing the interpretation that global risk aversion compresses the term premium gap through heightened short-term default concerns.

Figure 2. Yield responses to global risk aversion shocks

Our main results are robust to different measures of global risk aversion developed in the literature as well as to controlling for US monetary policy and for extreme events, such as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the Covid-19 pandemic period.

Figure 3. Term premium gap responses to global risk aversion shocks

In this analysis, we show that exogenous increases in global risk aversion widen sovereign spreads between EMEs and US yields more strongly at short maturities, thereby reducing the term premium gap. This pattern reflects a sharper deterioration in the creditworthiness of short-term EMEs bonds relative to comparable US Treasuries. By explicitly accounting for the entire term structure of spreads, our results highlight important maturity-dependent effects of global risk shocks. These findings enrich the literature on sovereign risk pricing in EMEs and offer useful insights for policymakers. Future research could extend the analysis to bonds issued in local currency.

Bekaert, G., Hoerova, M., and Lo Duca, M. (2013). Risk, uncertainty and monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(7):771—788.

Caldara, D. and Iacoviello, M. (2022). Measuring geopolitical risk. American Economic Review, 112(4):1194—1225.

Diebold, F. and Li, C. (2006). Forecasting the term structure of government bond yields. Journal of Econometrics, 130(2):337—364.

Flaccadoro, M. and Nispi Landi, V. (2025). Foreign monetary policy and domestic inflation in emerging markets. Journal of International Money and Finance, 159.

Flaccadoro, M. and Villa, S. (2025). Global risk aversion and the term premium gap in emerging market economies. Bank of Italy Working Paper Series, 1493.

Jordà, O. (2005). Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections. American Economic Review, 95(1):161—182.

Uribe, M. and Yue, V. Z. (2006). Country spreads and emerging countries: Who drives whom? Journal of International Economics, 69(1):6—36.

This approach is implemented in two steps. First, we obtain a daily measure of S&P 500 predicted monthly variance of returns, which is interpreted as the degree of uncertainty that financial markets expect over a calendar month. Second, we estimate the global risk aversion as the difference between the squared VIX and the fitted value of this regression.