This policy brief is based on Banque de France, Working Paper No. 995. The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Banque de France, the Eurosystem, or any other organisation with which they are affiliated.

Abstract

Using a new survey of French firms’ inflation expectations that predates the inflation spike, we document i) evidence on the anchoring of inflation expectations during the inflation surge, and ii) the relevance of inflation expectations for firms’ decisions. First, we show that inflation expectations under-responded to the initial surge but then persistently overshot actual inflation dynamics. As inflation rose, firms initially perceived inflation to be less persistent than in previous years, an effect that dissipated over time. Second, we find that inflation expectations correlate with firms’ wage and price decisions. One-year expectations matter more than long-term expectations. During the inflation surge, wage and price decisions became increasingly disconnected from inflation expectations. This suggests that the scope for wage-price spirals is likely more limited than one might have expected from the surge in inflation and inflation expectations.

As inflation reached levels unseen in recent decades across most advanced economies, a primary concern was whether this surge in inflation would become entrenched in inflation expectations, especially those of firms, given their role in setting prices and wages. However, due to the scarcity of surveys collecting firms’ inflation expectations, it has been difficult to assess how firms’ inflation expectations changed during this period, as well as whether those inflation expectations influenced firms’ price- and wage-setting behaviour. In Gautier, Savignac and Coibion (2025), we use a survey of firms in France conducted between 2020 and 2024 to examine these questions.

The Banque de France survey on inflation expectations has four unique characteristics that are not commonly available in other surveys of firms (Savignac et al., 2024). First, it covers the full inflation cycle starting in 2020 when inflation was close to 0 and finishing at the end of the disinflation process in 2024, which allows us to gauge how the inflation cycle affected the anchoring of inflation expectations. Second, the survey includes questions about inflation at different horizons, so it can speak to the persistence of the inflation process, as perceived by firms, and whether it changed along the inflation cycle. Third, it includes questions on firms’ expectations about the growth of wages in their firm over the next year, thereby providing an unusual link between aggregate inflation expectations and firm-level wage expectations. Finally, the survey also includes questions about the planned decisions of firms, such as their expected and past price changes and employment growth, so that expectations can be related to their decisions.

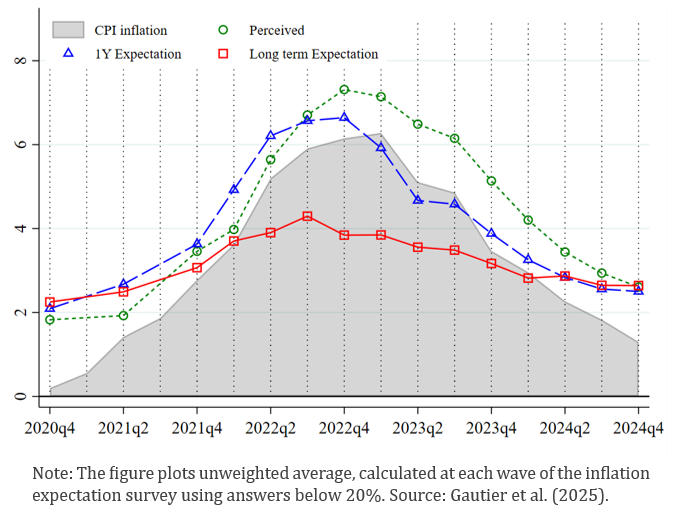

Using this unique data, we examine how inflation expectations responded first to the inflation surge and then to the disinflation process. In 2022, as inflation rose sharply in France, firms were initially surprised by the magnitude of the increase, with both their perceptions and expectations significantly underreacting (Figure 1). By 2023, however, both inflation perceptions and expectations of firms had significantly overshot actual inflation dynamics. This pattern of initial undershooting followed by overshooting aligns with the broader dynamics identified by Angeletos, Huo and Sastry (2021).

Figure 1. Average firms inflation expectations over time (in %)

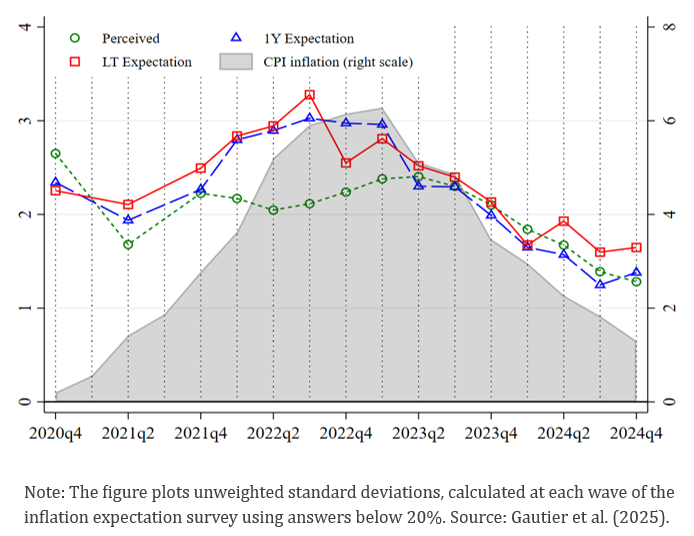

Second, we find that the average perception but also short- and long-term expectations of inflation all came back toward the target at the end of 2024. Thus, while all expectations deviated significantly from the inflation target during the surge, this deviation was relatively short-lived. Furthermore, disagreement among firms about future inflation rose sharply during this period, but the dispersion of expectations also decreased sharply during the disinflation process (Figure 2). We obtain similar conclusions for households based on the Consumer Expectations Survey (ECB) for France.

Figure 2. Standard deviation of firms’ inflation expectations over time (in %)

Third, as the inflation rate surged, the term structure of firms’ inflation expectations pointed to a decline in the perceived persistence of inflation, but this decline was short-lived. In other words, firms initially expected the rise in inflation to be more transitory than what they usually expected for inflation changes, but their expectations ultimately went back to assuming the same persistence as usual. One possible explanation for the decline in persistence could be that the inflation surge was initially tied to a sharp increase in energy prices, which might have been expected to have only a transitory effect on inflation dynamics. Regardless of the source, firms initially perceived the inflation spike as driven by a different process than during the low inflation period. Overall, and in contrast to the experience of other countries like the U.S. (e.g. Coibion and Gorodnichenko 2025), we do not find a significant persistent de-anchoring of inflation expectations following the inflation surge.

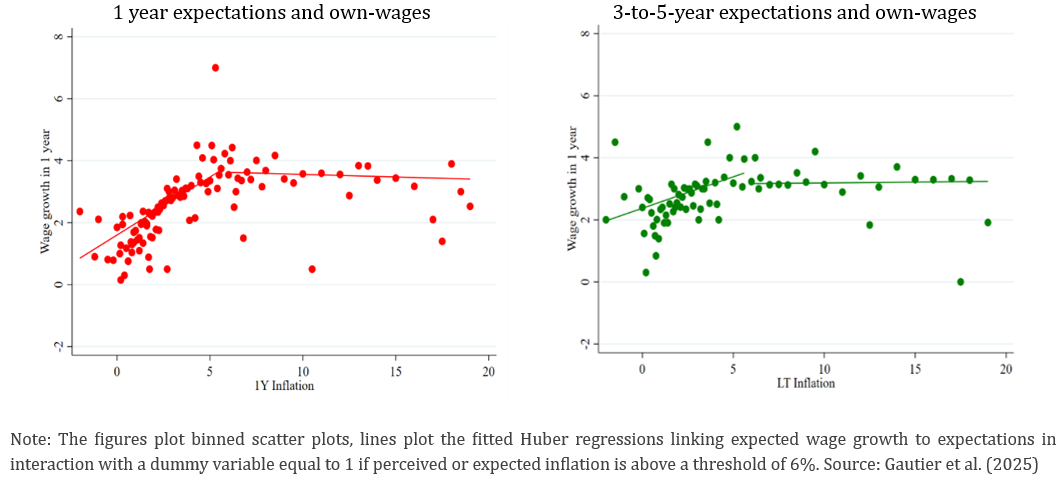

How do these expectations on aggregate inflation translate into the firms’ own-wage expectations? Two things jump out from Figure 3, which links wage expectations to inflation perceptions and expectations.

First, there seems to be a strong correlation between inflation perceptions and expected wage growth at low inflation levels, as well as for 12-month ahead inflation expectations with expected wage growth at low inflation levels. In contrast, there is little correlation between longer-run inflation expectations and wage expectations of firms. This appears qualitatively consistent with the logic of Werning (2022), who suggested that expectations embodied in fixed duration contracts should be limited to those with horizons overlapping with the duration of the contract. Here, the typical duration of collective wage agreements is one year and wages are also updated on average once a year (Gautier et al. 2022). Overall, we find that the estimated passthrough of inflation perceptions and short-term expectations into wage expectations amounts to 0.1 to 0.3 meaning that one additional percentage point in inflation perception/expectations is associated with 0.1 to 0.3 additional percentage point in wage expectations.

Second, the figure indicates that once inflation or expectations of inflation exceed a threshold at 6%, the relationship between inflation expectations and wage expectations breaks down. When estimating this passthrough, we find much larger passthrough coefficients for firms not expecting an inflation disaster (i.e. with inflation expectations lower than 10%). This suggests that inflation expectations matter less for wage decisions when they are far from being anchored. Their influence on wage setting seems to be much more pronounced when they are located in a more realistic range of values. During the inflation surge, disagreement among firms rose and the share of firms with such high levels of inflation expectations increased. This led to a weaker link between inflation and wage expectations during the high inflation period (i.e. when actual CPI inflation in France was higher than 3%), as the subset of firms who expected very high inflation did not expect to adjust their wages in response to this belief. As a result, inflation expectations did not seem to matter more during the inflation surge, contrary to what Jorda and Necchio (2023) found from wage Phillips curves estimated on US data and to the results obtained by Akarsu et al. (2025) on Turkish firms in a context of unanchored inflation expectations.

Figure 3. Price and Wage Inflation Correlations

Finally, we examine the extent to which inflation expectations translate into firm-level decisions—specifically regarding prices, employment, and production—and whether this relationship changed during the high-inflation period. We find evidence of a pronounced decline in the pass-through of expectations to these decisions. While the pass-through from expectations to ex-post prices and employment is strong in normal times, it weakened significantly during the high-inflation episode. This suggests that, despite a sharp rise in wage and inflation expectations, their actual influence on firm behavior – particularly price and employment adjustments – was muted during this period. This decline in pass-through is primarily driven by a subset of firms anticipating very high inflation (i.e. an “inflation disaster”). Among firms that did not foresee such an extreme scenario, the pass-through remained relatively stable across high or low inflation environments.

Our findings offer cautious reassurance to central bankers. The common wisdom is that expectations can potentially become unanchored during inflation spikes, which could tend to generate wage-price spirals. The case of France indicates that this does not have to happen. First, we find a growing disconnect between firms’ expectations about aggregate inflation (which rose sharply) and their expectations about their own-wage growth (which was much more muted). Second, the passthrough of expectations into prices and employment appears to have weakened significantly during the inflation surge. As a result, the sharp rise in inflation expectations and the more limited increase in own-wage expectations likely did not lead to as much upward pressure on inflation as one might have expected from earlier periods, thereby limiting the scope for any wage-price spiral dynamics and helping to explain why inflation in France remained relatively subdued compared to other countries. Our findings also suggest that surveys of firms’ expectations are an essential complement to household surveys, as firms may perceive inflation differently. While firms can be slow to update their expectations and occasionally exhibit alarmist views, they also tend to be pragmatic when making decisions about their own prices and wages.

Akarsu, Okan, Emrehan Aktug, Hzeyfe Torun, 2024, “Inflation Expectations and Firms’ Decisions in High Inflation: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial” mimeo, Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye.

Angeletos, George-Marios, Zhen Huo, and Karthik A. Sastry, 2021. “Imperfect Macroeconomic Expectations: Evidence and Theory,” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2020, volume 35, Eichenbaum and Hurst. 2021.

Coibion, Olivier and Yuriy Gorodnichenko, 2025. “Inflation, Expectations and Monetary Policy: What Have We Learned and To What End?”, NBER WP 33858.

Gautier, Erwan, Sébastien Roux and Milena Suarez Castillo, 2022. “How Do Wage Setting Institutions Affect Wage Rigidity? Evidence from French Micro Data”, Labour Economics, Volume 78, October 2022.

Gautier Erwan, Frédérique Savignac, Olivier Coibion, 2025. “Firms’ Inflation and Wage Expectations During the Inflation Surge,” NBER WP 33799.

Jordà Òscar, Fernanda Nechio, 2023. “Inflation and wage growth since the pandemic”, European Economic Review, 156, 104474.

Frédérique Savignac, Erwan Gautier, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Olivier Coibion, 2024. “Firms’ Inflation Expectations: New Evidence from France”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Volume 22, Issue 6, December 2024, Pages 2748–2781.

Werning, Ivan, 2022. “Expectations and the Rate of Inflation,” ” NBER Working Papers 30260.