References

Antolin-Diaz, J., Surico, P., 2022. The Long-Run Effects of Government Spending. Working Paper.

Batini, N., Di Serio, M., Fragetta, M., Melina, G., Waldron, A., 2022. Building back better: How big are green spending multipliers? Ecol. Econom.

Bils, M., Klenow, P.J., 2004. Some evidence on the importance of sticky prices. J. Polit. Econ. 112 (5), 947–985.

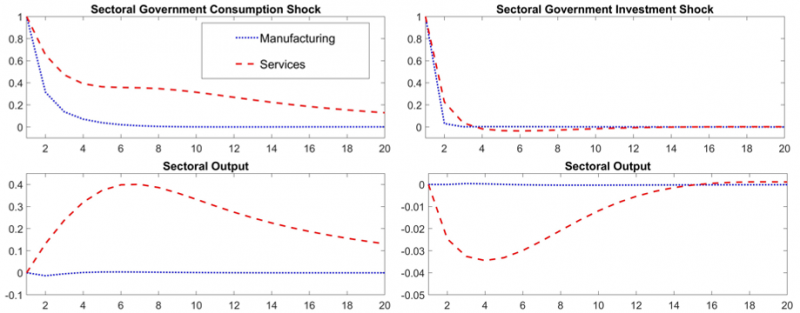

Boehm, C.E., 2020. Government consumption and investment: Does the composition of purchases affect the multiplier? J. Monetary Econ. 115 (C), 80–93.

Bouakez, H., Rachedi, O., Santoro, E., 2022. The sectoral origins of the spending multiplier.

Bouakez, H., Rachedi, O., Santoro, E., 2023. The government spending multiplier in a multi-sector economy. Am. Econ. J.: Macroecon. 15 (1), 209–239.

Cox, L., Müller, G., Pastén, E., Schoenle, R., Weber, M., 2020. Big G. Nber Working Papers, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Gabriel, R.D., Klein, M., Pessoa, A.S., 2023. The effects of government spending in the eurozone. J. Eur. Econom. Assoc..

Hasna, Z., 2022. The Grass Is Actually Greener on the Other Side: Evidence on Green Multipliers from the United States. Working Papers.

Klein, M., Linnemann, L., 2023. The composition of public spending and the inflationary effects of fiscal policy shocks.

Klenow, P.J., Kryvtsov, O., 2008. State-dependent or time-dependent pricing: Does it matter for recent U.S. inflation? Q. J. Econ. 123 (3), 863–904.

Nakamura, E., Steinsson, J., 2008. Five facts about prices: A reevaluation of menu cost models. Q. J. Econ. 123 (4), 1415–1464.

Ramey, V.A., 2020. The macroeconomic consequences of infrastructure investment. In: Economic Analysis and Infrastructure Investment. In: NBER Chapters, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, pp. 219–268.