The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the Federal Reserve System, or European Central Bank. We are grateful for comments by Armin Leistenschneider.

Abstract

Government bond trading is typically over-the-counter, with dealers playing a key role as intermediaries. Pressure on their intermediation capacity is set to increase as government debt continues to grow. We describe results from new research, which illustrates the risks of dislocation in major segments of the most important fixed income market, US Treasuries. We also provide a European perspective by highlighting key characteristics of EU government bond trading and the relevance of US policy work launched after the Covid dislocation for these markets.

The market for US Treasury securities is a crucial component of the global financial system, with more than $33 trillion outstanding at the end of 2023. Not only are Treasuries the primary means of financing the US federal government, but they are also a significant investment instrument and hedging vehicle for domestic and international investors and serve as a risk-free benchmark for many other financial instruments such as corporate bonds and mortgages. Treasuries are also essential for the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy implementation and transmission to the broader economy.

However, despite its size and importance, the Treasury market is intermediated by a select group of market-making financial firms—typically affiliated with large banking organizations. These so-called primary dealers participate directly in the primary market for Treasuries, where the US government auctions new debt issuance, and then resell the Treasuries to investors in the secondary markets.1

More generally, they act as intermediaries between sellers and buyers in the secondary market. Primary dealers are also direct business counterparties to the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy operations.

Given their crucial role, policy makers and academics have pointed out for some time the potential vulnerability of this dealer-centric market to changes in primary dealers’ constraints and their ability to efficiently intermediate the Treasury market (see, for example, Duffie, 2018, 2020, 2025). More recently, this discussion gained ground in the context of several recent disruptions in Treasury markets, significant accumulation of government debt in response to the COVID crisis, and projections of further increasing federal deficits.2

Against this background, on 13 December 2023, the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted a new regulation promoting central clearing of the US Treasury securities transactions. The Rule is designed to improve risk management practices and reinforce market resiliency, with eligible cash transactions as well as repo and reverse repo transactions being subject to mandatory central clearing starting at the end of 2026 and mid-2027 respectively. The Federal Reserve has also implemented measures that affect the Treasury market, such as modifying its reverse repo facility and introducing the Standing Repo Facility on July 28, 2021, to ensure dealer access to liquidity.

While these steps help making the Treasury market more resilient, potential vulnerabilities remain as other constraints may weigh on dealers’ intermediation capacity. First, due to their Bank-affiliation, dealers are constrained by banking regulation, specifically, capital and liquidity regulation. Indeed, in recent research, we show that the US implementation of the leverage ratio has significant effects on Treasury market liquidity (Bräuning and Stein, 2024). Second, dealers’ trading desks face internal risk management constraints, which could be influenced by regulation. In our research, we also show that primary dealers’ internal Value-at-Risk constraints affect the Treasury market. Value-at-Risk, or VaR, constraints limit the amount of losses tolerated from positions to certain maximum for a given probability, and they are the metric that banks use the most often to calculate and limit the risks that their trading desks take.

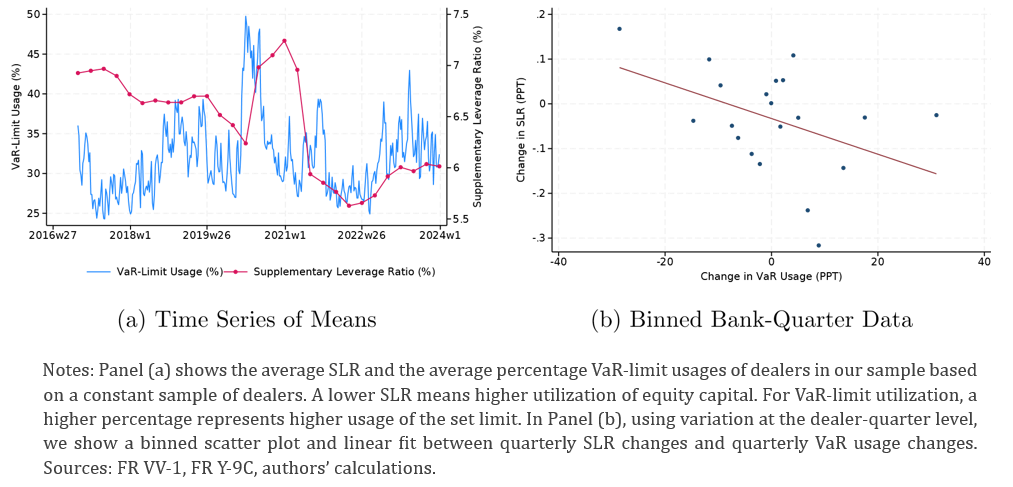

Interestingly, these two constraints are correlated in practice. Figure 1, Panel (a) shows the average supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) and VaR-limit usage over time, indicating substantial variation in both series as well as periods of co-movement.3 Using bank-quarter data, the binned scatterplot in Panel (b) shows a negative correlation between changes in VaR-limit usage and changes in the SLR; that is, periods when trading desks’ limits are heavily utilized are also periods when the SLR compresses. This could be because the Treasury holdings (positions) factor into both the utilization of VaR limits as well as the SLR through its exposure measure. Or it could be that when more equity capital is available at the bank level, VaR limits are eased.

Figure 1. Dealer Constraint Utilization: Leverage Ratio and Value-at-Risk

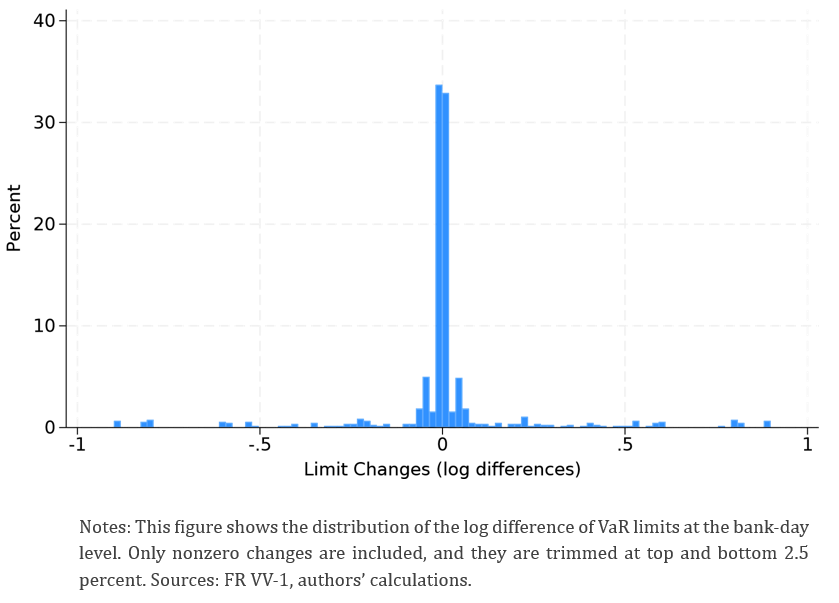

Our research uses detailed confidential microdata on banks’ risk limits, positions, and turnover, collected by the Federal Reserve, to study the effect of intermediary risk constraints on the Treasury market. Specifically, our data on VaR limits at the trading-desk level allows us to exploit changes to the VaR limits. While these VaR limits do not move often, Figure 2 shows a high kurtosis in the VaR limit change distribution, with several large limit changes above 10% in absolute value terms.

Our research shows that primary dealers decrease their net position in response to a tightening limit shock. Specifically, primary dealers reduce their net position by about 2.1 percent in response to a one-standard-deviation tightening limit shock. This can be rationalized by the dealer’s trade-off between the cost and benefit of holding a Treasury security. As dealers become more constrained, balance sheet space becomes more costly, leading to a reduction in the dealer’s position as some positions are not profitable anymore.

This reduction in dealer positions impacts overall Treasury market liquidity, as tighter limits also lead to lower turnover in the Treasury market. Intuitively, given that the majority of the plumbing of the Treasury market goes through a relatively small number of dealers and given that these dealers hold inventory in order to facilitate customer transactions, a reduction in dealer inventory results in a decrease in customer transactions and turnover. We find a one-standard-deviation limit shock leads to a decrease in turnover of about 2.1 percent. Given the average weekly turnover of about $360 billion, this corresponds to a decline in turnover of about $7.5 billion.

Furthermore, tighter VaR limits lead to wider bid–ask spreads: bid–ask spreads increase by about 2.7 percent in response to a one-standard-deviation limit shock. As VaR limits tighten and dealers become more constrained, they need to be compensated more per position, translating to wider bid-ask spreads.

The companion paper additionally shows that the tightening of VaR limits amplifies yield movements by about one-third and prompts less primary dealer bidding in Treasury auctions. It also causes the yield that clears the auction, known as the high yield, to increase, thereby constituting an increase in the government’s cost of financing itself.

Overall, it seems that as part of the Treasury market’s reliance on a select group of primary dealers from the banking sector, the changes in the risk limits of these dealers reverberate into the market, affecting turnover, bid-ask spreads, yields, and treasury auction results.

Figure 2. Distribution of VaR-Limit Changes

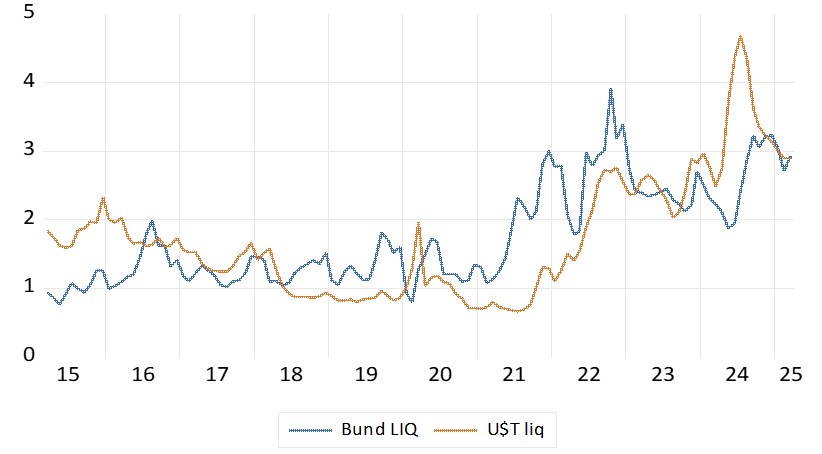

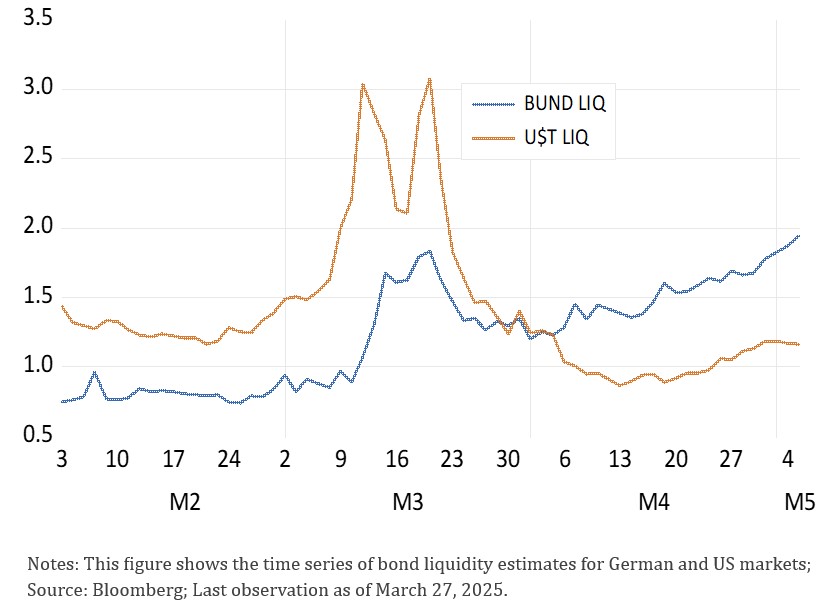

A brief comparison of trading conditions in US and German government bond markets over the last decade provides some background for our discussion of the European dimension of bond market resilience. A price-based measure of market liquidity indicates divergence in the trading conditions with a positive trend in the last two years (Figure 3a). In particular, (Figure 3b), the Covid shock had a larger impact in the US Treasury market compared to Bunds.

For the interpretation of the evolution of market liquidity it is important to compare the trading infrastructure of the US and European government bond markets. Similar to the US market, also EU trading is dealer-dependent, with a high reliance on bank dealers. “Speed”, i.e., the extent of electronic trading of trading is quite heterogeneous and can be categorized along the lines of the segmentation in the US Treasury. The recently issued, “on-the run” (benchmark) Treasury bonds are traded among dealers using high-speed electronic trading protocols, which resemble the trading structure on organized exchanges. In contrast, older “off the run” Treasury bonds rely on voice and bilateral trading. In Europe, the bonds of Germany and many euro area countries are also traded similar to US off the run bonds on OTC venues (Abbassi et al, 2024). The main exception is the Italian government bond market, where electronic platforms are widespread and therefore resemble US benchmark bond trading. Two additional market segments are also vital for government bond market liquidity. The repo market serves as a source of funding for bond trading and arbitrage and usually works via slower platforms, similar to the US. In contrast, bond futures are traded on organized exchanges and therefore fully centrally cleared in both US and Europe (see Scheicher, 2023 for a survey).

Against this background we now discuss how the four main elements of the G-30 proposal outlined above map to the European environment:

In comparison to the granular analysis of US Dealer capacity work on EU fixed income markets is less extensive, partly due to data availability. Breckenfelder and Ivanshina (2021) show that the introduction of the leverage ratio for European banks affected corporate bond liquidity. For instance, they find that if a Dealer with existing underwriting ties is one percentage point closer to capital requirement, the bid-ask spreads of the corresponding bond increases by 4 basis points. Another channel is the significant fall in balance sheet repo volumes around quarter- and year-ends, which highlights “window-dressing” (Bassi et al., 2024). Repo market fragility is also affected by growing NBFI activity (cf. O’Donnell and Tamburini, 2025).

UK gilt market functioning also provides evidence for dealer constraints and fragile intermediation in Europe. A fiscal policy shock due to surprises in a “mini-budget” in September 2022 led to a major dislocation in UK fixed income markets (cf. Pinter, 2023). Selling pressure in gilts driven by liability-driven investors (LDI) strongly affected market liquidity, especially in long-maturity gilts and inflation-linked bonds. Dealer constraints are also highlighted by Baranova et al (2023) who show that expanding central clearing of cash gilt and gilt repos could foster intermediation capacity, by increasing the netting of buy and sell trades, which would reduce the burden on Dealer balance sheets and capital ratios. For instance, wider netting in the gilt repo market could cut Dealers’ gilt repo exposures by 40%. Finally, Bicu-Lieb et al (2020) find a decline in gilt repo liquidity around the announcement of the UK leverage ratio regulation. Gilt liquidity worsened conditional on factors such as funding costs and inventory risk. There is evidence that gilt repo liquidity has become less resilient, although heterogeneity among Dealer firms is material.

At the time of writing, EU market participants have highlighted in a survey that the leverage ratio may be constraining for their repo business.7 Nevertheless, most dealers do not report any major constraints in their bond and repo market making business at the current juncture.

Figure 3. A price-based measure of trading conditions in US and German government bond markets

Figure 3a. Evolution over last ten years

Figure 3b. Evolution during Covid dislocation

As discussed in FSB (2020) and BIS (2021), international workstreams have been launched to tackle some of the broader lessons from the March 2020 turmoil.

One key area is focusing on NBFIs, e.g., enhancing their liquidity preparedness. The NBFI sector is quite heterogeneous and comprises asset managers, hedge funds, insurers and trading firms. In this context, the Bank of England has recently launched a Contingent Non-Bank Financial Institution Repo Facility (CNRF).8 The new facility, which will only be activated during episodes of severe gilt market dysfunction, will lend to participating insurance companies, pension schemes and liability driven investment funds to help maintain financial stability.

Another topic is the design of central bank policy in periods of market stress. In this context, Kashyap et al. (2025) provide a new proposal for “hedged-purchase approaches” which would focus on off-setting positions in bonds and the corresponding futures thereby directly targeting basis arbitrage.

In April 2025, tariff announcements by the US administration led to very high volatility in the Treasury market. Due to rising selling pressure in the cash segment some dealers reportedly reached their intermediation limits (cf. IMF 2025).

Abbassi, P.; M. Bianchi, D. Della Gatta, R. Gallo, H. Gohlke, D. Krause, A. Miglietta, L. Moller, J. Orben, Jens; O. Panzarino, D. Ruzzi, W. Scherrieble and M. Schmidt (2024) “The German and Italian government bond markets: The role of banks versus non-banks.” Deutsche Bundesbank Technical Paper 12/2024

Arseneau, D., M. Carlson, K. Chen, M. Darst, D. Kirkeeng, E. Klee, M. Malloy, B. Malin, E. O’Malley, F. Niepmann, M. Styczynski, M. Vanouse and A. P. Vardoulakis (2025). “Central bank liquidity facilities around the world.” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Baranova, Y, E Holbrook, D MacDonald, W Rawstorne, N Vause and G Waddington (2023). “The potential impact of broader central clearing on dealer balance sheet capacity: a case study of UK gilt and gilt repo markets.” Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 1,026.

Barone, J., A. Chaboud, A. Copeland, C. Kavoussi, F. Keane and Seth Searls (2022) “The Global Dash for Cash: Why Sovereign Bond Market Functioning Varied across Jurisdictions in March 2020.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1010.

Bassi, C., M. Behn, M. Grill and M. Waibel (2023) “Window dressing of Regulatory Metrics: Evidence from Repo Markets.” SUERF Policy Brief 569

Bicu-Lieb, A., L. Chen and D. Elliott (2020) „The leverage ratio and liquidity in the gilt and gilt repo markets.” Journal of Financial Markets, Volume 48, 100510.

Brauning, F., and H. Stein (2024) “The Effect of Primary Dealer Constraints on Intermediation in the Treasury Market.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Research Department Working Papers, 24-7.

Breckenfelder, J. and V. Ivashina (2021) “Bank Balance Sheet Constraints and Bond Liquidity.” ECB Working Paper 2589

Duffie, D. (2018). “Financial Regulatory Reform After the Crisis: An Assessment.” Management Science, 64(10): 4835–4857.

Duffie, D. (2020) “Still the World’s Safe Haven? Redesigning the U.S. Treasury Market After the COVID-19 Crisis.” Brookings Hutchins Center Working Paper.

Duffie, D. (2025) “How US Treasuries Can Remain the World’s Safe Haven.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 39(2): 195–214.

Duffie, D, M Fleming, F Keane, C Nelson, O Shachar and P Van Tassel (2023) “Dealer Capacity and U.S. Treasury Market Functionality.” BIS Working paper 1138

Financial Stability Board (2022) “Liquidity in Core Government Bond Markets.” FSB Report

Group of Thirty (2021) “U.S. Treasury Markets: Steps Toward Increased Resilience. G30 Working Group on Treasury Market Liquidity”.

IMF (2025) “Global Financial Stability Report”, chapter 1.

Kashyap, A.J., Stein, J. L. Wallen and J. Younger (2025) “Treasury Market Dysfunction and the Role of the Central Bank.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

O’Donnell, C. and F. Tamburrini (2025) “Central clearing and the growing presence of non-bank financial intermediation in euro area government bond repo markets.” Published as part of the Macroprudential Bulletin 26.

Pinter, G. (2023) “An Anatomy of the 2022 Gilt Market Crisis.” Mimeo.

Scheicher, M. (2023) “Intermediation in US and EU bond and swap markets: stylised facts, trends and impact of the COVID-19 crisis in March 2020.” ESRB Occasional papers, Number 24.

In secondary markets, Principal Trading firms (PTFs) are also active as intermediaries.

For example, https://www.wsj.com/finance/why-treasury-auctions-have-wall-street-onedge-8385f15e

Both SLR and VaR are constrained to exceed a certain threshold (imposed by regulation or management), but the optimal target SLR and VaR may well diverge from the constraint in practice. Therefore, the SLR and VaR-utilization ratio is not necessarily informative about how constrained a given bank is.

See Arseneau et al (2025) for a concise international comparison of central bank liquidity facilities.

The first selection procedure for the tape was launched by ESMA on 3 January 2025.

Under the EU framework, EU GSIB Dealers currently typically achieve a leverage ratio around 4.5%.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/groups/pdf/mmcg/20240313/20250313_MMCG_Item_3a_Intermediation_capacity_survey_results.pdf

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/news/2025/january/boe-open-new-contingent-non-bank-lending-facility-for-applications