The paper shows that the lack of a complete institutional framework in the Eurozone is one of the reasons for the disappointing performance over the last few years. This in turn fuels dissatisfaction with the European institutions, because they are not delivering what people expect, leading them to think that we may need less Europe, rather than more Europe. We need to address this catch-22, by further working on a detailed design of a more complete institutional framework for the European Union and by pushing political authorities to be more courageous in implementing reforms.

The publication of the book “Architects of the Euro” by Kenneth Dyson and Ivo Maes is a good opportunity to take stock of the current state of the architecture of the Euro, and what is still missing for its smooth and effective functioning on a lasting basis. The Euro needs to be completed in at least two key dimensions.

The first concerns the economic and monetary union. The second concerns the environment in which such a union is supposed to operate, what we would call the political union.

The architects of the euro knew from the very start that EMU, as it was conceived at the time, given political feasibility, was incomplete. A complete union, with all the characteristics of a political union could not be implemented, as we saw with the Werner Plan. The Werner Plan was certainly broader in scope, and probably more consistent in terms of complementarity between the various components, but it could not be implemented because it was too encompassing. Some would say it was unrealistic.

A good architect must take reality into account, such as the force of gravity that he/she can certainly challenge but never ignore. The architects of the euro – back then and now – must understand what is feasible given underlying economic and political forces at play. In particular, we should never forget that the main underlying economic and political foundations of Europe are based on democracy, on the democratic will of the people in the various member states. Any decision to share sovereignty needs to be approved by the people, directly or through their elected representatives.

This is often forgotten, especially by those who like to present Europe as the result of technocratic decisions. At every step, the decision to share sovereignty, which involved in particular amendments to the Treaty – whose 60th anniversary will be celebrated in March 2017 – implied a democratic ratification by the member states. The difficulties in some of these ratifications, such as the rejection of the Treaty establishing a European Constitution in 2005, should remind us of the democratic nature of the process.

The principle of subsidiarity, which is at the heart of the European project, suggests that sovereignty should be shared only on matters were it is less efficient to exercise it at the national level. And it is up to the people, through the democratic process of the respective countries, to decide whether it is more efficient – and desirable – to exercise sovereignty at the national or at the European level.

How can the case be made for sharing sovereignty? How can it be clear to the people that sovereignty has not been well exercised at the national level?

One answer is: “when there is a crisis”. This is what led Jean Monnet to state that “Europe will be forged in crises, and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises”. This means – quite unfortunately – that you need crises to implement change in Europe, to transfer sovereignty to the Union. The problem is that crises are not a good time to design new institutions. Crises generate tensions between member states, which tend to reduce mutual trust. Without trust, the design of the new institutions tends to be imperfect. Think about the European Stability Mechanism, which has a cumbersome governance, including the requirement of unanimity in order to decide whether to provide financial support to a member state in difficulty. This self-imposed requirement amounts to giving any member state a veto power, that no country enjoys in similar international fora, such as the IMF.

When the crisis strikes, and there are no pre-existing plans to address the main shortcomings of the prevailing institutions, solutions tend to be suboptimal. The crisis may be wasted. If instead plans already exist which policy-makers can take from the drawer – as it was the case for instance for the ECB – there is no need to improvise. The plan can easily be implemented. This means that architects should not wait for a crisis before thinking about the plans that have to be drawn for the next stage of integration. We need plans to be available beforehand – even if they look unrealistic at the time – so that they can be readily adopted when the time comes.

Architects thus need to think ahead, and appear to be somewhat “utopian”, or “idealistic”, because the time may not have come yet for their ideas to be fully realized. But they will be realized when the time comes, and we know that a crisis sooner or later will come, unfortunately, because any incomplete design is bound to show its weaknesses when put to the test of a major shock.

This has been the European experience for many years. And it has been true for the euro. Not many thought that the introduction of the euro in 1999 would be the final step towards economic and monetary union. In particular, it was certainly not optimal to start a single currency without a fully integrated banking regulation and supervision. But a complete scheme, which included not only monetary union but also financial integration, was not feasible from the start. The member states had just accepted to give up their monetary powers, how could they be expected to deprive themselves of regulation and supervision? Strengthening cooperation should be sufficient! “If cooperation worked, why should it be changed?” – that was the mantra at the time.

The system was not able to pass the test of the 2010-11 crisis. The stress tests conducted by national supervisors on their own banks turned out not to be credible – because so different from each other. The doom-loop between the sovereign and the banking risk started to develop.

Only when the shortcomings of the old system became apparent, could it be agreed that a further move towards a more integrated union was necessary, i.e. that we needed “more Europe” also in the financial sector. Only at that point the national authorities agreed to share their powers and responsibilities at the European level and created a single authority in charge of supervision.

Fortunately, when the times were mature for the decision to be made, a lot of work had already been done. The Lamfalussy and the de Larosie re Reports had been prepared in the previous decade, underlying the limits of coordination. Work had been done by the ECB and by some academics and think-tanks. An enabling article had been foreseen in the ECB statutes, to prepare for the possibility that supervisory tasks would be attributed to the central bank. The institution was ready to host the new powers.

The crisis showed that the countries which experienced the largest banking losses in Europe, and where the taxpayer had contributed most, were those where the banking supervisor was less independent and the most distant from the central bank. This evidence helped convince that the ECB was the right place where supervisory responsibilities should be located. In short, when the consensus emerged that supervision had to be centralized, a plan was readily available and it didn’t take much time to dis-cuss it, agree on it and implement it.

A different result was achieved with the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) which was created in May 2010 and transformed one year later into the ESM. When Greece got into trouble, in early 2010, it became clear that the Eurozone lacked a shock absorber to help countries that had lost market access to finance their adjustment. It took not only the crisis in financial markets but also the refusal of the ECB to be – once again – “the only game in town”, for the European Council to finally agree on creating the Facility, in early May 2010, that was supposed to be transformed into a fully-fledged system within a few months. The lack of a precise plan at the long transition led to the creation of a cumbersome institution, with a complex and un-transparent decision-making process that provides for veto power to all member states.

The discussion which took place in the course of 2010 and 2011 contributed to the uncertainty. The most obvious example is the so-called Deauville Franco-German proposal – which was later ratified by all countries – to implement an automatic bail-in of private investors whenever a country applied for financial assistance, independently of its debt sustainability. This proposal, which had not been thoroughly thought through, heightened the tensions between the member states, and with the ECB, and contributed to delaying the economic recovery.

This is why plans are needed before crises erupt, so that they can be assessed and adopted quickly, and thus help getting out of the crisis more rapidly. This is why we need architects to work ahead of crises, to develop plans that may seem unrealistic at the time but may quickly become very useful to policy-makers.

This is not to say that we should simply accept that domestic political requirements should dictate the European agenda and that institutional changes should be put on the backburner until the next crisis comes. While it may be true that crises help better understand the need to complete the institutional framework, we should not underestimate the costs deriving from the lack of a complete framework. In other words, the absence of stronger European institutions is felt not only at times of crises, but also in “normal times”.

Let me briefly illustrate this issue using data that are often ignored.

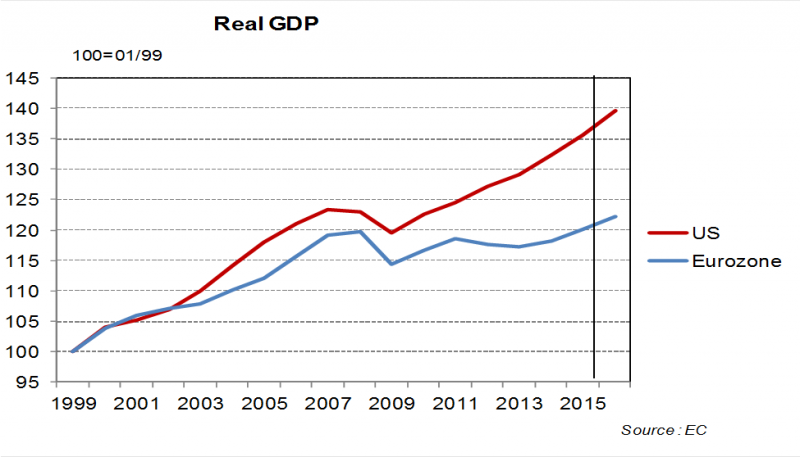

When we assess the current situation in the Eurozone, in particular in comparison with the United States, we tend to underscore the difference in growth and economic performance over the last few years, in particular since the 2008-09 crisis. What comes immediately to mind is that we have not yet fully recovered from the pre-crisis levels, as GDP is just coming back – for the average of the area – to the 2007-2008 levels, while the US is much above, by around 10 percentage points, as shown in the next figure. The unemployment rate in the Eurozone is higher, nearly twice as high as in the US. A similar unfavorable position would emerge from the comparison with the UK or even Japan.

There are several reasons for the worse performance. I will not list them all, but – for sure – the failure of the European institutional framework comes to mind, and much has been done during the crisis to repair it. However, when it comes to the main recipes for fostering growth in Europe, the accent is often put on structural reforms, a better use of the fiscal space, and the pursuit of an expansionary monetary policy. The focus is generally not on the institutional framework.

The Five Presidents’ Report, which puts the accent on the need to complete the Economic and Monetary Union, implicitly endorses this view. For the first stage, to last until the end of next year, nothing much is foreseen in institutional terms. Its title is “deepening by doing”, whatever these words may mean. In the second stage, whose length is uncertain, “the convergence process would be made more binding through a set of commonly agreed benchmarks for convergence that could be given a legal nature.” Only in 2025 the third stage is expected to start, with a complete institutional framework.

I would like to put forward the hypothesis that the incompleteness of the union, at least until 2025, is a key factor explaining the disappointing eco-nomic performance over recent years, and going forward. Such disappointing performance may foster the sentiment that Europe is not fulfilling its promises and thus fuel populist resentment and disaffection. In other words, the incompleteness of the Union may be the cause for the disenchantment towards the European project itself.

We should thus raise the question of whether it is appropriate to wait for the third stage, or for the next crisis, to make further progress towards a stronger union. Can we really take it for granted that when the next crisis will come, the forces of integration will prevail over the centrifugal pressures? Can Europe continue to progress, from crisis to crisis, or is there the risk that a rejection of the whole project might at some stage look like the best way forward, as has been the case with the British referendum?

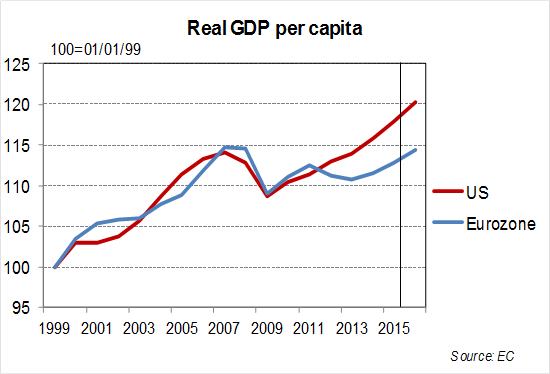

Looking more closely to the comparison between the Eurozone and US performances, it is interesting to note that between 2000 and 2008 the two areas experienced more or less the same rate of GDP growth, taking into account the difference in demographic trends. In other words, excluding population growth and considering GDP per capita, the Eurozone and US have performed quite similarly until the crisis, as the next chart shows. In fact, even after the crisis, from 2009 to 2011 the recovery was quite similar. In fact, in 2011 – on average – Eurozone per capita GDP was slightly higher than in 2007, while in the US, Japan and the UK it was slightly lower. In the year 2011 the Eurozone per capita GDP rose by 1.4%, more than in the US and the UK (0.9%) as well as Japan (-0.3%).

Thus, until 2011 the Eurozone did not behave very differently, in spite of the structural differences and the different policy responses to the crisis. This is not to say that Europe does not need to implement structural reforms, but rather that the developments prior to the crisis do not suggest that structural factors made a very big difference. In fact, the Eurozone created more jobs than the US in the first decade of this century.

Looking closely at the recent years, the main difference in performance was experienced after 2012-13. The Eurozone went through a recession, with a fall in GDP by 1.1% and 0.5% respectively, while the US, Japan and the UK continued to grow. The Eurozone recovery started only after 2014, but at a slower pace than in the other areas. In short, the Eurozone experienced a double-dip recession, while other countries had only one recession in 2008-09.

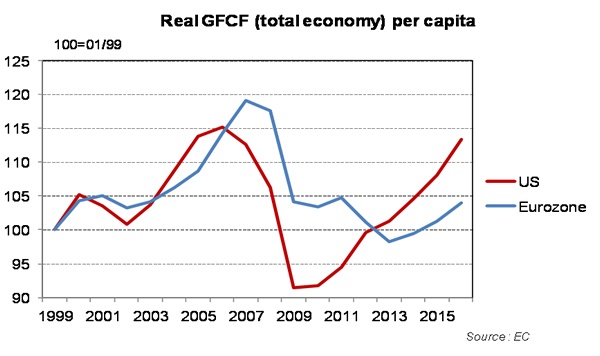

The key component of the double dip is investment. In 2012 and 2013 total Eurozone investment fell by 3.3% and 2.6%, against a rise of 6.3% and 2.4% in the US and 3.4% and 3.2% in Japan.

The contraction was experienced throughout the Eurozone, including not only the so-called periphery, but also the core. Germany’s investments fell by 0.4% in 2012 and 1.3% in 2013. In the Netherlands the contraction was 6.3% and 4.4%, respectively. Investment started to recover only in 2014-16 but at a slower pace than in the US.

What does the data suggest? Something fundamen-tal happened in the Eurozone in 2011-12, that aborted the recovery, produced two years of recession, and is currently slowing down growth.

We all know what happened in 2011-12. The Eurozone experienced a major crisis, with the doom loop between bank and sovereign risk which led to a spike in Government bond yields and huge tensions in the financial markets. Such a big crisis affected all countries, not only the periphery, but also the core, as shown by the German data.

Since the crisis, several actions have been undertaken. The ECB launched its “whatever it takes”, which reduced the risk of disruption of the Eurozone, and its Asset Purchase Program. The Single Supervisory Mechanism was created and banking union was started. Progress has been achieved in several countries under adjustment programs.

The question is whether these actions have put the Eurozone back on track to a sustainable growth, so as to catch up the ground lost during the crisis. The answer is negative.

Looking at the recent data, the average Eurozone growth has remained below that of the US, even in countries such as Germany which have come out relatively better than others from the crisis. Unemployment has fallen but remains comparatively high.

This suggests that pursuing structural reforms and restoring budgetary discipline is certainly essential in the current environment, but is not sufficient. If the differences in structure do not explain why Europe performed as well as the US before the crisis, can they explain the difference after the crisis?

This is why a new – possibly additional – hypothesis needs to be considered, i.e. that the actions taken so far in the institutional area are not sufficient to enable the Eurozone to grow again at its full potential. Macro and structural policies, even if they had more space and were implemented more forcefully, would not be enough. This means that as long as the institutional framework is not reinforced, growth in the Eurozone will remain subdued and will lag behind.

In fact, without further institutional strengthen-ing, there is a risk that other ammunitions, notably in the fiscal and monetary domain, are wasted.

What is the link between the institutional framework and economic growth, in particular investment? As we all know, investors need a stable environment to take decisions. The higher the uncertainty – of a political, social, economic nature – the lesser are the incentives to invest.

We are living in times of high uncertainty, at the global level. However, Europe has an additional dimension of uncertainty, an existential dimension, which affects the whole European construction.

We have had – and we are still having – a direct experience of such an uncertainty with Brexit. The whole world, in particular the one which enjoys democracy, is experiencing the rejection of elites by those that feel left behind by globalization. In the European context, this has also led to questioning supranational institutions, considered responsible of all the wrongdoings. While it may be easy to overthrow or replace the national – or local – elite, it seems to be less easy to do the same at the European level. Exiting may be easier. “If you can’t beat them, lose them!” could be the modern version of the popular saying.

This risk is particularly high when national politicians tend to shift the blame for any negative event on Europe, in the hope of saving themselves. Even the pro-European politicians, who advocate “not being against Europe, but being against this kind of Europe” are becoming less appealing than those who promote a much more straightforward concept, like “if we can’t reform Europe, let’s just as well quit it”.

While the advent of a new, populist ruling class at the global level may translate into a substantial change in policies, in the European case it may imply putting the membership of the Union into question, which entails consequences of a completely different dimension. In Europe, any uncertainty about the outcome of elections or any hardship experienced during a crisis may have existential implications. The fact that a country might leave the Eurozone, or that the Eurozone itself might implode, has a totally different impact on an investment decision than a change in policy or in government within a given unchanged institutional set-up.

The commitment to the euro that ruling politicians repeatedly make are an attempt to reduce the uncertainty, but cannot distract from the fact that the question about the future of the Eurozone, and its membership, continues to be asked at conferences and investment fora, especially outside of Europe. The complexity of the project is an additional obstacle for those trying to understand whether it will be resilient to shocks in the future. The fact that a “muddling-through” policy worked quite effectively in the past is not necessarily seen as a good reason why it will work in the future. The doubts about the sustainability of the European project, expressed in particular outside the continent, are fueled not only by the emergence of populist anti-European sentiment but also by the lack of convergence of key fundamentals.

Let me focus on the financial sector. Consider for instance the so-called Target2 balances, which reflect the creditor and debtor positions of European banks within the central bank payment system. The data show that the gross creditor and debtor positions have not decreased, and in fact continue to rise. This may be in part due to technical factors, linked to the way in which the ECB implements its quantitative easing. But it also suggests that banks still prefer to hold deposits at the ECB rather than lend to banks in other countries. The interbank money market has not fully recovered since the crisis. A possible interpretation is that banks consider that lending to banks located in other countries is still too risky.

Another indicator to look at is the integration of the Eurozone financial sector. Nearly two years after the start of the banking union, there is little progress. Banks are focusing increasingly on their domestic market, “re-nationalizing” their activities. There has been no cross-border merger, while some consolidation has started within borders. This may be the result of remaining regulatory obstacles to cross-border consolidation, of the incomplete nature of banking union – in particular with respect to the lack of a common deposit guarantee – or the uncertainty related to the long term prospects of the Eurozone.

The banking union is not complete, and its incompleteness fuels fragmentation which slows down cross border financial flows. The uncertainty about the further steps that need to be implemented to complete the union slows down investment and economic growth.

To sum up, the last crisis – which is the deepest since the inception of the Union – has raised doubts about the sustainability of the Union itself, in particular the Eurozone. In spite of the progress which has been accomplished so far, the doubts have not disappeared. They represent a major risk for entrepreneurs starting a business or wanting to expand in the continent. The fact that some of the reforms that are required to credibly reduce the risk of disruption, such as a more centralized fiscal policy or a fully-fledged banking union, do not appear politically feasible in the near term, tend to reinforce these doubts. These doubts in turn tend to weaken the Eurozone economy and fuel further imbalances. The Eurozone is the area in the world with the highest excess of savings over investment, which translates into a current account surplus (around 3% of GDP). This excess fuels the broader savings glut at the global level, which is responsible for the low level of interest rates. The main message is that the lack of a complete institutional framework in the Eurozone is one of the reasons for the unsatisfactory performance over the last few years. Growth has picked up, but not sufficiently, and the recovery remains fragile. This in turn fuels dissatisfaction with the European institutions, because they are not delivering what people expect, and in the end lead people to think that we need less Europe, rather than more Europe.

How can we get out of this catch-22?

The answer is that we need more architects – new architects – to prepare the detailed design of a more complete institutional framework for the European Union. These architects may today look like utopists, out of space, idealists. Like the revolutionaries of the old times they may have to work out of the limelight, against the current, waiting for the right time for their ideas to be shared. But sooner or later the need for their plans will be vital. In fact, I am convinced that sound and rational plans for moving forward towards a more complete union could be easily understood and accepted by the European people, if they see that this is a way to address the problems of their everyday life. What we need, first and foremost, is more courageous politicians, that are not afraid of reforming their countries and the Union because they may lose their job at the next election. They are bound to lose their job anyway, unless they understand that the only way for their own countries to prosper in this global world is to rely on a successful Europe.

The Policy Note is based on a speech held by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi at the Belgian Financial Forum on 18 November 2016.