The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Bank of Slovakia (NBS)

Abstract

The post-pandemic inflation surge tested monetary policy frameworks around the world, and the outcomes can inform future policy framework choices. This is particularly the case for EU countries still outside the euro area, most of them in Central-Eastern Europe (CEE). The recent inflation-fighting record of the four Visegrad countries (Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia – ‘V4’) provided a “natural experiment” to examine monetary policy outcomes under two different monetary regimes, yet with broadly similar economic characteristics. Slovakia joined Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) in 2009, whereas Czechia, Hungary and Poland remained outside. We compare the inflation performance of the V4 countries under the two different monetary regimes and find that euro area membership was quite beneficial. It allowed Slovakia to restore price stability at a lower cost in terms of monetary policy tightening than its neighbours, and a more effective crisis management at times of stress.

The post-pandemic inflation period tested monetary frameworks across the globe, with satisfactory results overall. After a spectacular surge in inflation in 2022–2023, most advanced and emerging market economies have brought inflation back under control. Country experiences differed, however. Emerging markets (EMs) initiated monetary policy tightening about a year earlier than advanced economies. This allowed them to fight inflation more gradually – though with higher interest rates – and to reverse monetary tightening earlier on. By contrast, advanced economies such as the US, UK, Australia and the euro area reacted later to the rise in inflation, necessitating a faster space of interest rate increases with potentially higher risks to financial sector stability and more convoluted central bank communication (Evdokimova et al. 2024).

In this paper we take a closer look at this recent high inflation period in the CEE region, which experienced a sort of “natural experiment” with structurally similar countries living under two different monetary regimes: Slovakia as an EMU member and Czechia, Hungary, and Poland as countries outside the EMU with independent monetary policy. Drawing on our recent joint paper (2024), we consider how this episode can inform the complex debate on the pros and cons of euro adoption in the CEE economies that are still outside the euro area.

It is important to note at the outset that within the euro area, CEE member countries – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia – had considerably higher post-pandemic inflation rates than the euro area average. Falagiarda (2024) explains this primarily with significant differences in economic structure between the CEE countries and the rest of the euro area, such as higher CEE exposure to global shocks such as disruptions in global supply chains and the economic consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Falagiarda also points to higher unit profit increases in CEE euro area countries than elsewhere, linked, inter alia, to less competition and to tighter labour market conditions in CEE. The European Central Bank (ECB) cannot, of course, react to such country-specific differences within a monetary union, so that fiscal, macroprudential and structural policies must bear the brunt of any necessary country-specific adjustments.

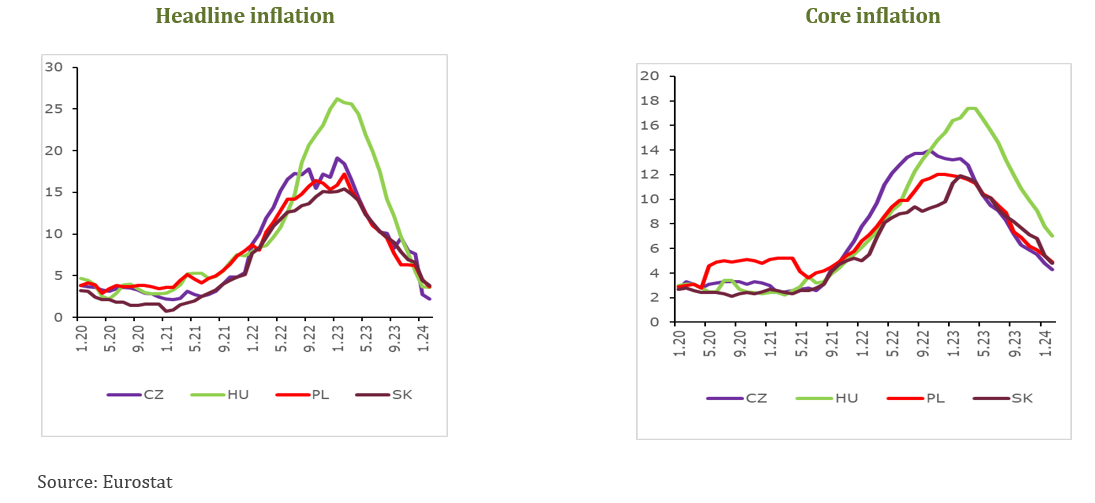

V4 countries’ headline inflation, as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), started to rise almost at the same time in the fall of 2021, albeit from higher initial levels in the three non-EMU countries compared to Slovakia. Hungary’s inflation was already above its central bank’s inflation target of 3 per cent (with +/- 1 per cent tolerance band) at the beginning of the period. Core inflation also started to rise in the fall of 2021, except for Poland, where core inflation was already elevated in the spring of 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Inflation in V4 countries

Hungary experienced the highest headline inflation among the V4 countries with over 25 per cent in late 2022. Inflation reached around 15–17 per cent in the other Visegrad countries, including Slovakia, where price increases were only a bit lower than in Czechia. All of these countries’ inflation rates were significantly higher than the euro area’s average peak rate of slightly over 10 per cent in the fall of 2022.

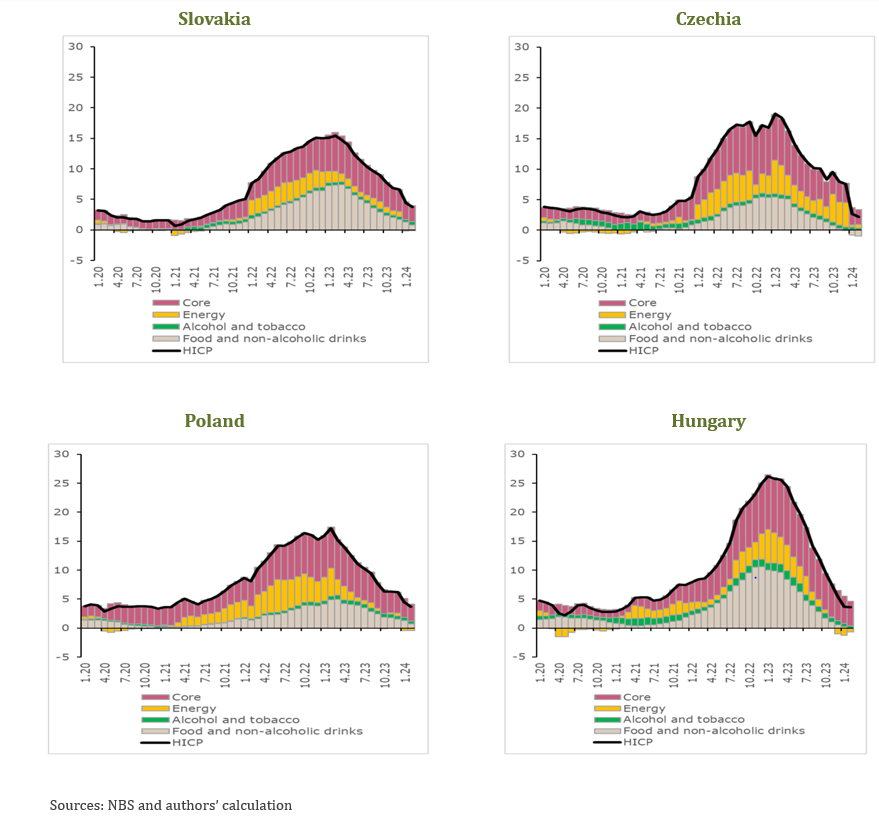

The energy price shock in early 2022 was a key driver of inflation in each country, particularly in Slovakia and Hungary (Figure 2). Food inflation played a particular role in Hungary and Slovakia, reflecting not only the impact of higher energy prices in the agriculture and food processing sectors, but also drought effects and unfavourable weather conditions. Core inflation was especially high in Hungary, followed by Czechia and Poland, and, to a lesser extent, Slovakia.

Figure 2. Inflation components in the V4 countries (%)

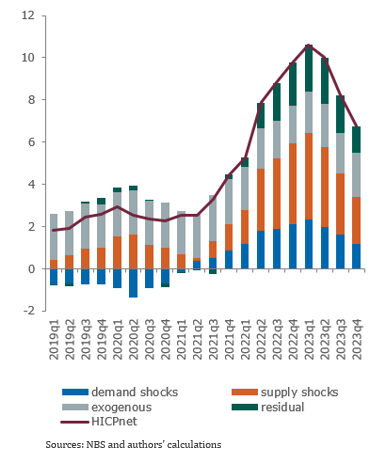

Zooming in on Slovakia, we calculate demand and supply side contributions to headline HICP inflation (Figure 3). In the period 2020–2023 Slovakia, like the other V4 countries, witnessed a “perfect inflation storm”. The Covid pandemic initially suppressed demand and limited supply in many ways, such as lockdowns, quarantines and social distancing measures. These led to disruptions in global supply chains to which CEE’s globally integrated markets are particularly sensitive. Fiscal measures implemented from the spring of 2020 to support households and enterprises added to demand pressures and increased imbalances in supply and demand. As vaccination became widely available, social distancing was curbed and supply constraints eased. But soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, resulting in another negative (energy) supply shock.

Figure 3. Slovakia: contributions to HIPC inflation (year-on-year, %)

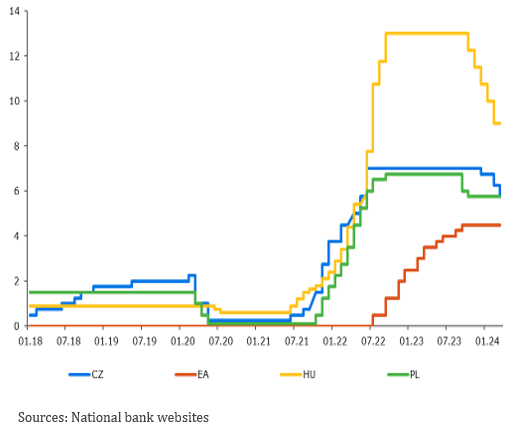

Monetary policy responded to inflationary pressures earlier in the three non-euro area CEE countries than in Slovakia (with a difference of up to a year) (Figure 4). As mentioned, this was in line with the observed global trend of emerging market central banks reacting faster to the rise in inflation than their advanced country counterparts, underpinned by improved monetary policy frameworks including in the CEE region.

Interest rates were raised to much higher levels in the three non-euro area countries than in the EMU/Slovakia. Given its record level of inflation, Hungary’s interest rates were increased the most. However, real interest rates remained negative for some time in all V4 countries, as well as in the euro area, the US and the UK.

Czechia and Poland experienced broadly similar – though higher – inflation rates to Slovakia, but Slovakia had substantially lower nominal interest rates within EMU, resulting in more deeply negative real interest rates for some time. This could, in principle, lead to a decline in the real value of debt and thus more buoyant domestic conditions.

Did Slovakia suffer in terms of fighting inflation because of the later and more muted monetary policy tightening by the ECB? Did ECB monetary policy lead to additional demand pressures in Slovakia relative to the other V4 countries? Inflation performance does not suggest so. In fact, inflation in Slovakia started to come down roughly at the same time as in the other V4 countries (except Hungary). A belated and less severe EMU monetary policy reaction was enough to bring inflation down roughly at the same time as in the other V4 countries. The common monetary policy did not “penalise” Slovakia by creating additional prices pressures or extending the high inflation period. On the contrary, it imposed a lower output-cost via much lower interest rates that were needed to bring inflation down.

Figure 4. Policy rates in the Visegrad 3 and EMU/Slovakia

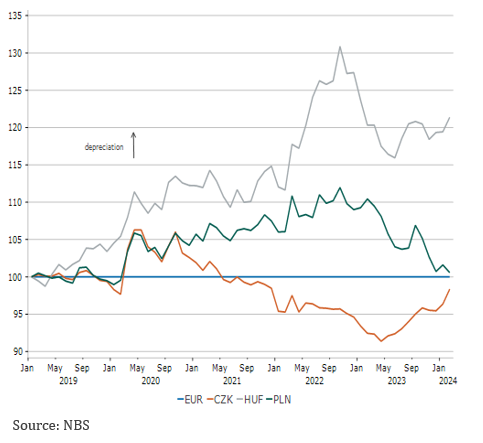

Currency developments influenced inflationary paths. The currencies of the three Visegrad countries outside the euro area exhibited wide fluctuations against the euro (and the US dollar), although less so for Czechia. The Hungarian forint and, to a lesser extent, the Polish zloty depreciated against the euro at the start of the pandemic in March 2020 and again after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which fed into price increases (Figure 5). It is critical to highlight that currency depreciations may have been much higher in Poland and Hungary (and several other countries in the region) without the ECB’s foreign exchange swap and repo operation support at the height of the market stress, such as in March–April 2020.1 As EMU member, Slovakia naturally did not have to worry about euro liquidity or exchange rate fluctuations against the euro. Its adoption of the euro and the backing of the ECB’s massive balance sheet made crisis management incomparably easier.

Figure 5. Currency movements vis-à-vis the euro (Jan 2019= 100)

Currency Unit/EUR (Jan 2019 = 100)

Fiscal policy influenced the post-pandemic inflation surge in two important ways: (i) via expansionary fiscal policies, first related to pandemic support to households and businesses, and then via energy subsidies in the wake of the surge in energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Figure 6); and (ii) by “providing shelter” to households and firms from the impact of monetary policy action, for example in the form of interest rate caps for certain activities or borrowers.

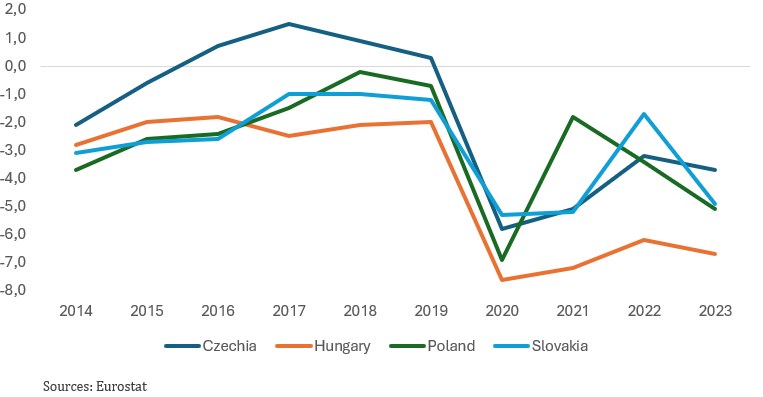

The V4 countries entered the pandemic period with relatively sound fiscal positions in terms of moderate levels of public debt and small deficits. The pandemic crisis management measures, however, increased fiscal deficits substantially across the region from 2020 onwards. The fiscal deficit remained particularly high for long in Hungary (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Fiscal balance in V4 (% of GDP)

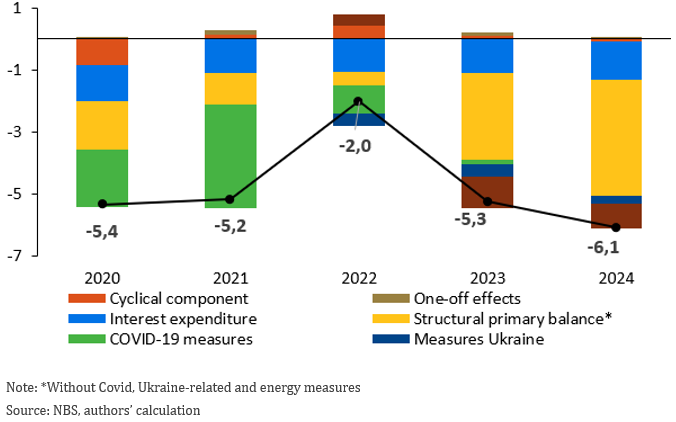

We examine Slovakia’s fiscal record in more detail (Figure 7). The Covid-related fiscal measures of 2020–2021 were taken at a time when inflation was (still) relatively low. Some of the measures explaining the substantial deficits during 2023 and 2024, however, such as increased social benefits and direct energy support measures contributed to inflation.

Figure 7. Slovakia: Fiscal balance decomposition (% of GDP)

In Poland, the “Anti-Inflation Shield” measures introduced in early 2022 – a reduction in VAT and excises on a range of food and service items – are estimated to have contained inflation temporarily for one year by some 4 percentage points (IMF 2023). In Hungary, limiting utility and energy price increases and related open and de facto subsidies were also significant. For example, the government specifically introduced caps on interest rate increases (“kamatsapka”), which weakened the pass-through of policy interest rate increases to prices. In addition, it provided below-market interest rate loans under various government schemes (Coen-Bech et al. 2023). More significant fiscal consolidation took place in Czechia in 2022–2024, supporting inflation reduction but also contributing to weaker domestic demand and growth.

The V4 countries made remarkable progress towards convergence since their EU membership in 2004. Recent studies prepared around the 20th anniversary of EU membership identify a significant “EU accession bonus” in the growth performance for the countries that joined in 2004.2 However, within the V4 group we observe some country differences with regards to growth performance and convergence. Convergence in Slovakia seems to have stalled in recent years, possibly along with Czechia, though it also slowed in other V4 countries.

Analysing the reasons behind this trend is beyond the scope of this study but given that – in our view erroneously – some observers blame the convergence slowdown on EMU participation, a few comments should be made. It is true that EMU membership puts a much bigger onus on national fiscal policies and structural-regulatory reforms. This is even more so the case for smaller economies, which often benefit from lower interest rates and more abundant liquidity than outside EMU. What EMU members do with this depends largely on the countries themselves. Some have taken a proactive role and accelerated structural reforms and investing in human capital, such as Finland and Ireland. Others have taken a more complacent approach to reforms, which may be the case in Portugal (de Souza 2024).

Looking at the situation in the V4 countries, productivity growth has declined in the past decade or so albeit this is a more general phenomenon. The reasons for this are complex but public investment has for example “flatlined” in Slovakia, because EU funds tended to substitute rather than add to national public investment. In Poland and Hungary, public investment also declined, and there were at times issues with the ability to access EU funds, due to governance compliance issues.

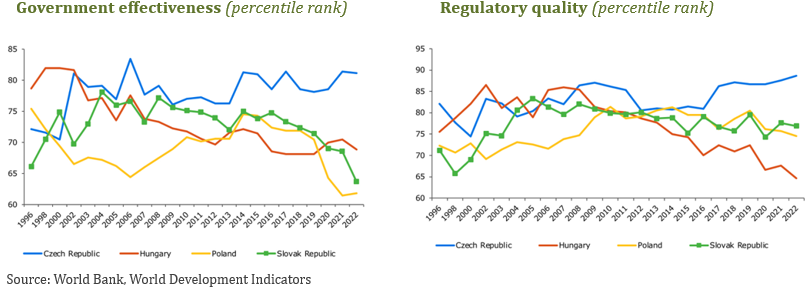

We also observe a trend decline in government effectiveness and, to some extent, regulatory quality, which might have played a role in the convergence slowdown, though Czechia is an exception (Figure 8).

While there is little evidence that EMU membership in itself provides major benefits for real convergence, there is also no evidence to the contrary. The single most important lesson to learn when it comes to EMU membership and growth is to avoid complacency and take good advantage of available funding options for productivity-increasing investment in human and physical capital as well as innovation in a more business-friendly environment.

Figure 8. “Doing business” in the V4, 1996–2022

We analysed the recent post-pandemic inflation period in the four Visegrad countries. Given their similar economic structures and context, the inflation surge under two different regimes – with Slovakia being EMU member and the other three countries pursuing independent monetary policy – can be seen as a “natural experiment” to test the impact of euro area versus national monetary policy in small, open economies.

Our findings are as follows:

What do these findings imply for euro membership of the current non-EMU EU countries? In our view, the conclusions are rather clear. For small, open, highly integrated economies, de facto monetary sovereignty is quite limited. By contrast, membership in a very large monetary union, encompassing the main trading partners and benefitting from the credibility and – if needed – crisis management capacity of the ECB, provides clear benefits, even in case of very large, multiple supply-side shocks to inflation.

Cohn-Bech, E., Foda, K., Roitman, A. (2023): Drivers of Inflation: Hungary. Selected Issues Paper No. 2023/004, International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/selected-issues-papers/Issues/2023/02/27/Drivers-of-Inflation-Hungary-530224

De Souza, L.V. (2024): Unhappy Anniversary: Missed opportunities for growth and convergence in Portugal. CEPR VoxEU, 11 March. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/unhappy-anniversary-missed-opportunities-growth-and-convergence-portugal

EBRD (2024): Regional Economic Prospects (May 2024). European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). https://www.ebrd.com/rep-may-2024.pdf

Falagiarda, M. (2024): Inflation in the eastern euro area: reasons and risks. ECB Blog, 10 January. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2024/html/ecb.blog240110~4901f29da7.en.html

Greene, M. (2024): Who is buying? Outlook for consumption in a rate cutting cycle. Speech, The North East Chambers of Commerce, Newcastle, 25 September. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2024/september/whos-buying-speech-by-megan-greene.pdf

Grossi, B., (2024): The EU Miracle: When 75 Million Reach High Income. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19114. CEPR Press, Paris & London. https://cepr.org/publications/dp19114

IMF (2023): Republic of Poland: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report. European Department, International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400244216.002

IMF (2024): Regional Economic Outlook for Europe: Soft Landing in Crosswinds for a Lasting Recovery. International Monetary Fund, 19 April. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400272363.086

Evdokimova, T., Nagy Mohácsi, P., Ponomarenko, O., and Ribakova, E. (2024): Breaking down success: How emerging markets have outperformed the Fed and the ECB, VoxEU, February 24, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/breaking-down-success-how-emerging-market-central-banks-have-outperformed-fed-and-ecb

Panetta, F. – Schnabel, I. (2020): The provision of euro liquidity through the ECB’s swap and repo operations: ECB Blog, 19 August. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2020/html/ecb.blog200819~0d1d04504a.en.html

Martin, R. and Nagy Mohacsi, P. (2024) Fighting Inflation within the Monetary Union and Outside: The Case of the Visegrad 4 (December), https://hitelintezetiszemle.mnb.hu/en/fer-23-4-st6-martin-nagy-mohacsi

Rey, H. (2015): Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence. NBER Working Paper No. 21162. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21162

For a summary of the ECB’s motivation behind its currency swap and repo operations, see Panetta and Schnabel (2020).

The EBRD (2024) finds that compared to Germany, this group of countries observed a convergence of 24 percent in per capita income, of which 14 per cent is an “EU accession bonus”, that gave rise to faster GDP and real income growth. Grossi (2024) similarly finds a significant “EU bonus” for this group of countries.