Note: This policy brief is based on a keynote speech delivered at the Bank of Finland & SUERF Conference on “Monetary Policy Implementation: Old Wisdoms and New Trends” in Helsinki, on 11 June 2025.

Abstract

This policy brief explores how the central banks, the Eurosystem in particular, are transitioning toward a new phase in monetary policy implementation—one shaped by lessons from the past decade of unconventional policy, evolving market structures, and the need for greater adaptability. It outlines three central themes: the appropriate size and composition of the central bank balance sheet, the design of liquidity tools to balance rate control and financial stability, and the evolving role of reserves, including the future of minimum reserve requirements. Emphasizing flexibility, data-driven adjustment, and the importance of active engagement from the central banking community, the policy brief frames the ECB’s 2024 operational framework update as a foundation—rather than a finish line—for future policy refinement and resilience.

“It’s a new dawn, it’s a new day …” and, at least for those of us who spend our days occupied by the mechanics of operational frameworks, it just might be a new life for monetary policy implementation.

I promise not to sing like Nina Simone, or any of the other great voices who have recorded the classic song Feeling Good. But I believe that the spirit of that song captures something essential about where we find ourselves today. After years of unconventional measures, swollen balance sheets, and abundant reserves, combined with shifts in financial market structures, technology and regulation, we are clearly entering a new phase.

We are rethinking how monetary policy should be implemented in a new, more “normal” environment – whatever that may mean in a world where economic policies are redrawn every morning in the Truth Social.

But, let me borrow the spirit of Nina Simone’s question: Are we feeling good? Are we confident that our frameworks are fit for purpose?

This policy brief offers an important opportunity to reflect on those questions. Even among central bankers, implementation details are sometimes treated as a footnote. But we at the Bank of Finland believe this conference helps to fill still existing gaps. After all, how we implement monetary policy does shape the financial system and its infrastructure in a fundamental way.

I will first outline three interrelated key themes we must confront as we design the next stage of our implementation frameworks: the size and role of central bank balance sheet, the design of central bank liquidity tools, and the role of the reserves market.

Let’s begin with a brief overview of where we currently stand.

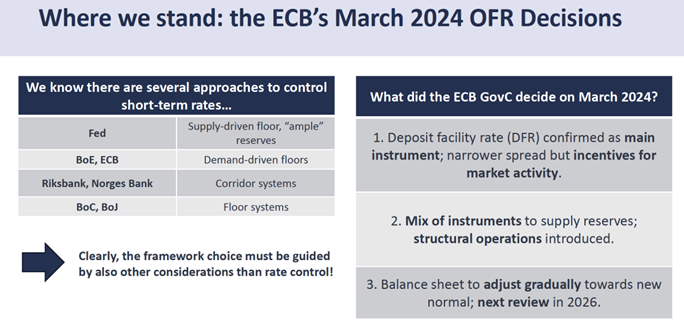

We know central banks can use different approaches to control short-term interest rates. The Federal Reserve operates with ample reserves, the Bank of England uses a demand-driven floor system, and the Swedish Riksbank has opted for a narrow corridor. All these approaches work well. They all achieve their core objective: control over short-term interest rates.

Since multiple frameworks can achieve their ultimate goal, the choice must be guided by other considerations: how each framework interacts with the financial system, the incentives it creates and side effects it implies. In other words, the design of an implementation framework is not just about whether it works, but how it works in practice and solves the associated trade-offs.

In March 2024, the ECB Governing Council decided to move toward a demand-driven system. The new framework resembles the Bank of England’s model in several respects, but of course, it reflects the unique characteristics of the euro area: its bank-based financial system, heterogeneity, and the institutional design in the single currency area.

Let me briefly recap the key elements of the Eurosystem’s updated framework:

Finally, the balance sheet will not remain permanently oversized. However, the adjustment process will be gradual, allowing us to assess how our tools perform, how markets develop and adapt as needed. The next formal review, scheduled for 2026, gives us flexibility along the way.

Now, let’s take a step back and examine some broader implementation questions that apply not only to the Eurosystem but to central banks more generally.

A central question, one I’m sure others will also raise today, is: What is the appropriate size of the central bank balance sheet? And how should we approach the transition?

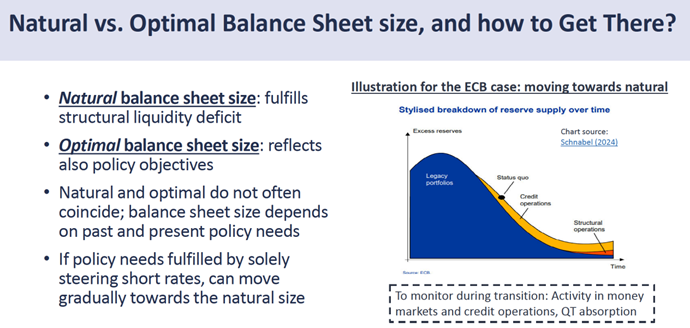

A helpful distinction here is between the natural and the optimal size.

The natural size is the minimum needed to meet the structural liquidity needs of the banking system. For the central banks issuing a reserve currency, like the Eurosystem, typically the liability side dominates. That is, the demand for banknotes and reserves exceeds central bank’s basic demand for assets like foreign exchange reserves. This kind of a structural liquidity deficit is met through policy operations on the asset side, typically by providing banks with refinancing operations and/or holding a securities portfolio.

The optimal balance sheet size goes beyond the natural one. It incorporates policy objectives and some trade-offs. A larger balance sheet can reduce short-term rate volatility and support financial stability, at least in the short run, but it also expands the central bank’s footprint in financial markets, reduces incentives for market activity, and may introduce moral hazard.

There is no universal one-size-fits-all answer to the optimal balance sheet size. It evolves with the financial system and institutional context. One unresolved question is whether abundant reserves (or large balance sheet) genuinely enhance financial stability. Recall the 2023 US banking turmoil: Silicon Valley Bank and some others collapsed despite abundant reserves in the U.S. banking system. Conversely, in the euro area, abundant reserves may have helped to shield banks from contagion.

Ultimately, the size and composition of the balance sheet reflect both past and present policy needs. For example, in 2020, the pandemic pushed the optimal size far above the natural level. This illustrates the key point: the natural and optimal sizes do not always, or even often, coincide. But when steering short-term rates is sufficient, the optimal and natural balance sheet sizes can over time converge.

In the future, we will be moving (in the euro area) to a hybrid model, having a structural outright portfolio together with lending operations. The marginal reserve unit will be supplied through the latter, in a demand-driven manner.

As we transition from today’s oversized balance sheet, three elements are particularly important:

So far, we’ve seen no signs of reserve scarcity. But our new operational framework must be ready before scarcity re-emerges. And it’s not just about us, banks must also be ready to use the tools as intended.

To conclude this section, given the uncertainties, we need not only a steady-state balance sheet, but also a credible transition path, one that remains flexible and data-driven.

Now to my second topic: the design of liquidity tools.

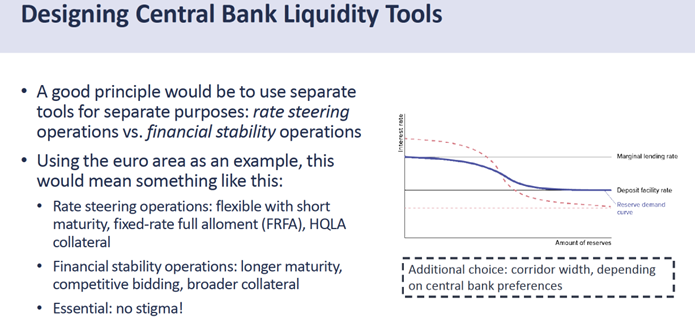

I’ve long argued for a clear distinction between two types of operations: first, short-term operations to control the short market rates, and second, structural longer-term operations aimed at enhancing financial stability.

For the euro area this could mean:

First, tiered collateral framework: Limit short-term policy operations to high-quality liquid assets (HQLA), while accepting the broader range of collateral in longer-term operations. This would support the control over interest rates and put limits to regulatory arbitrage, much like the Bank of England’s approach.

Second, different tender procedures: fixed-rate full allotment (FRFA) is ideal for short-term operations. Indeed, one of the main findings in my PhD thesis, already over 20 years ago was precisely that fixed-rate operations offer the best control over short-term rates, especially when banks’ demand for reserves is uncertain. FRFA adjusts reserve supply quickly, also supporting financial stability and even liquidity in bank resolution if needed. And we can go beyond the current weekly operations: why not consider an open-ended 24/7/365 facility at the policy rate against high quality liquid assets?

In contrast to the operations in which the central bank acts as a rate setter, competitive auctions make more sense for longer-term operations. Acting as a rate taker in these financial stability-oriented operations reduces distortions, puts a price on enhanced liquidity transformation, and reveals information on reserve demand.

Third, no stigma: credit operations must be seen as a normal part of the toolkit. Several central banks are encouraging banks to use facilities in the future. From my perspective, the two main features to prevent stigma are: 1) if the price of borrowing reserves directly from the central bank does not exceed the market rate, the use of central bank facilities should not result in a separating equilibrium, and in any case 2) the institutions using the central bank operations or facilities should not be disclosed.

Finally, the width of the interest rate corridor matters. Whereas rate volatility grows with the width of the corridor, a wider corridor provides more room for market activity. Hence, the optimal width depends on central bank preferences regarding rate volatility and market footprint. In the Eurosystem, the Governing Council opted last year for a 15-basis-point spread between the deposit facility rate and main refinancing rate.

That said, different frameworks may work equally well in different contexts.

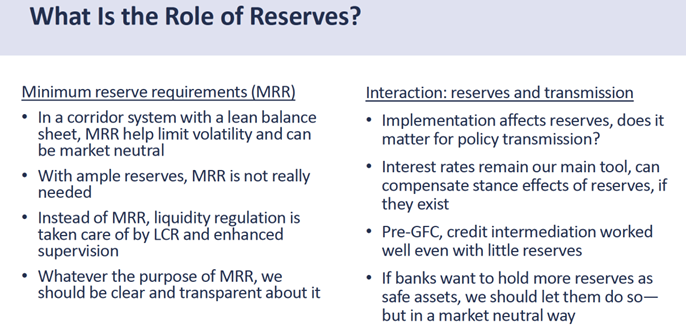

Let me close with a few reflections on reserves and in particular minimum reserve requirements (MRR), and their function in the operational framework.

In a corridor framework with a lean balance sheet, MRR limits rate volatility and is market-neutral, if remunerated appropriately.

But in ample reserve or demand-driven floor regimes, like the Fed or the BoE, MRR plays no real role in rate control. This is evidenced also by the fact that neither the Fed nor the BoE have MRR. Today, the other historical function of reserve requirements, liquidity assurance, is largely covered by the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and other supervisory tools.

If one applies MRR, one should be clear about its aim, and this should also drive its design. Do we aim at better rate control, monetary policy effectiveness, financial stability, or central bank income? Currently, minimum reserves are not remunerated by the Eurosystem. MRR are not currently needed to reduce short-term rate volatility. It functions more like a tax, countering the effect tiering had when negative interests were applied.

More broadly on the role of reserves in transmission. The choices on the design of monetary policy implementation affect the amount of reserves in the banking system. But is this an issue from monetary policy transmission perspective?

While we should be mindful of the links between implementation and transmission, policy rate, our most effective and best understood tool, will remain the primary tool for setting the monetary policy stance also in the future. Furthermore, any potential impact from our implementation choices to the policy stance e.g. via credit intermediation can be taken into account while setting the policy rate.

We managed fine pre-GFC with far less reserves. Still, if banks want to hold more safe assets in the form of reserves than 20 years ago, let’s allow that, in a market neutral way. Perhaps they should even be allowed to pre-commit to a certain level of reserve holdings and access them via long-term structural credit operations at competitive prices.

In this respect, I see merit in the idea of voluntary reserve requirements.

Even if demand for reserves proves higher than expected, that does not mean central banks need to hold massive securities portfolios and accept related risks. In bank-based economies, especially currency unions without fiscal unions, structural credit operations may be a more efficient and targeted way to supply liquidity.

Let me conclude by returning to the question I posed at the beginning: Are we feeling good?

After reflecting on the progress we’ve made, I’d say: I feel better than James Brown.

But seriously, this is a moment of opportunity. The Eurosystem has a solid operational foundation. Now is the time to learn, refine, and adapt. We’re not starting from scratch. We’re building on years of experience, evidence, and excellent collaboration within the central banking community.

Our framework is not static. The insights we get from conferences like this improve its evolution. We still face many open questions: how the adopted frameworks perform in practice, how markets react, and how implementation choices support broader policy goals.

Because let’s not forget: the operational framework we design today will shape the financial system and its infrastructure and define how monetary policy works in the next crisis.