The European fiscal rules are criticised on the one hand for the lack of scope for stabilisation, the lack of incentives for public investment, and the pressure towards very low debt. On the other hand, it is criticised that the implementation is lax, while high debt ratios are not reduced. This article discusses options which may reconcile these competing objectives. On the one hand, a sufficiently ambitious target, which reduces high debt ratios, should be binding. To this end, predictability should be improved, the scope for discretion reduced and the budgetary surveillance be transferred to an independent, non-political institution. On the other hand, a prudently designed expenditure rule and, in particular, national rainy day funds could increase room for fiscal manoeuvre. If the inclusion of government investment in the rules would be considered a suitable design should limit fiscal risks. Therefore, a “capped golden rule” is introduced. It combines a swift reduction of high debt ratios with protection for investment.

Sound public finances are crucial for a stability-oriented monetary union. They ensure that the Member States have market access and they safeguard a stability-oriented monetary policy. Monetary policy could suffer from fiscal dominance if confidence in sound public finances is lost. In such a situation it could come under pressure to assist fiscal policy sacrificing price stability. Within the European monetary union (EMU), Member States decide their own fiscal and economic policy. It therefore follows that Member States have to raise their own funding on the financial markets. Monetary financing by the Eurosystem and joint liability are prohibited by the treaties. Therefore, the ESM was created as a lender of last resort, although it does not provide unconditional assistance, and it is ultimately the Member States that decide whether and how to service government debt. In such an ambitiously designed monetary union, it is more necessary to avoid high debt ratios than in a framework in which monetary policy is conducted at the national level and debt is denominated in national currency. While fiscal rules cannot force through sound public finances, they should aim to achieve this and thereby strengthen market confidence.

The current low interest rates certainly make it easier for governments to shoulder their debt. They allow for less ambitious primary balances to achieve deficit targets. Yet high debt levels remain a risk – particularly in a monetary union. The currently very low interest rates must not be viewed as a permanent phenomenon. It would be risky, if they tempted governments to pursue a strategy of high debt levels.2 Otherwise, rising interest rates may quickly erode confidence in the soundness of public finances, with adverse effects on Member States and the monetary union. Even fiscal problems in a single country may be a heavy burden for monetary policy and risk giving rise to fiscal dominance.

Therefore, European budget rules should continue to aim at reducing high debt ratios and at maintaining sound positions. The current general goals, particularly the medium-term objective (MTO), do reflect this intention. The MTO is a budget that is close to balance in structural terms and depends on the size of the debt ratio. Where debt ratios are higher, the MTO is limited to a structural deficit of 0.5% of GDP. Where debt ratios are significantly below 60%, the MTO may be set less ambitiously – currently up to 1%.

The MTO, in general, should become more binding again. While some flexibility is appropriate and some complexity is unavoidable, the rules and their implementation still have to be transparent and predictable. This is becoming less and less the case.

At the same time there is scope for adjustments, which take on board criticism without compromising on the objective of sound public finances. To this end, the following aspects will be looked at: expenditure rules, rainy day funds and golden rules to protect investment.

Fiscal rules should be concrete and transparent. This allows fiscal developments to be assessed and treated in a comparable manner over time and between Member States. The European rules instead provide ample room for discretion, permitting deviations from the basic quantitative objectives. An improvement would be to significantly limit the exceptions, which are often neither clearly defined nor coherently justified. The implementation should be rules-based. All in all, policymakers as well as the general public should be able to understand the fiscal rules and their implementation.

Fiscal rules form a counterweight to short-term incentives in the political process to finance budgets with debt. Therefore, fiscal surveillance by political institutions is disadvantageous. Less political institutions are usually deemed to be more appropriate. Yet, the European Commission is the key player in fiscal surveillance at the European level, and it sees itself as a political institution. It weighs up its different policy objectives in the negotiation process with the Member States and the aim of the fiscal rules recedes into the background. Implementing the fiscal rules have become more of a political bargaining process than a rules-based process.

As limits are only effective if breaches are reported and penalised, it would be advisable to transfer fiscal surveillance to an independent institution. To offset political incentives, the competent authority should have a clear and narrow mandate and should not pursue conflicting objectives. Its tasks would be to flag up breaches of the rules, quantify adjustment paths according to terms agreed in advance and recommend procedural steps. Discretion should be strictly limited against the backdrop of relatively clear rules. Council decisions, which may still be made at the end of the process, would thus be prepared less politically. One could, for example, consider transferring the task of surveillance to the ESM and enhancing its independence in this particular area.

A frequent proposal is that expenditure ceilings should feature more prominently in the rules. This could indeed simplify the rules to some extent. However, there are drawbacks to expenditure rules and it would be important to take them into account when designing the rules.

Under the European rules, the MTO and adjustment needs (with a view to reaching the MTO) are defined as a structural balance or its change. Structural goals are intended to allow the automatic stabilisers to “breathe”. Like all target variables for budget rules, structural goals have specific inherent problems. But overall, while not being perfect, they are reasonable anchor points for budget rules and should therefore be retained – possibly operationalised with expenditure rules.

Expenditure rules may ease the problem that it is not always possible to unerringly achieve concrete structural balance targets. Obstacles are unexpected developments in revenues or overall economic output. Such forecast errors could cause structural balance objectives to be missed, although the budget plans have otherwise been implemented as planned. To meet targets despite unexpected developments, the implementation of the budget would have to be adjusted ad hoc within the budget year. This could trigger an erratic fiscal path and even after the budget year is over, an ex post revision could lead to a deviation from target. In order to cope with this problem, complex corrections and special assessments are currently carried out within the fiscal rules. As a result, transparency is lost and it is nearly impossible to identify why a requirement is considered as having been met or missed.

An expenditure rule could simplify budget execution and could make the assessment process more transparent. The structural balance to be achieved in the coming year could be translated into a corresponding maximum level of expenditure growth. This ceiling would then be the benchmark for assessing compliance with the rules in the year in question. Deviations in other categories or revisions of the cyclical adjustment would be excused.

Nevertheless, an expenditure rule is not as simple as it seems at first sight. It is difficult to implement and monitor such a rule in the individual government entities of a strongly decentralised or federal Member State. Moreover, it would be important to ensure that the expenditure ceiling is adjusted if there are any active measures on the revenue side. A tax cut, for example, should lead to a more ambitious expenditure target. A tax increase may be used to finance additional expenditure.

For the expenditure rule to be effective, it is essential that it is based on realistic forecasts. This is particularly true for the projections of i) profit-related taxes, which are especially hard to estimate, ii) changes in tax legislation, and iii) tax enforcement. If the respective revenue forecasts generally had an optimistic bias, the permissible expenditure growth would be set too high. The objectives for the structural balance would then regularly be exceeded and, thereby, the targets softened. In order to address false incentives, independent surveillance authorities could validate the forecasts and plans.

Moreover, it would be strongly advisable for the maximum expenditure growth to be determined annually, i.e. only for the coming year. For the following year, it would then have to be newly derived from the current, rule-compliant structural balance or from the required improvement in the structural balance. If expenditure targets were to span a number of years, there would be a risk that deficits rise over this period without countermeasures being taken. Rising debt ratios and accumulated future correction needs would be the result. For example, if economic activity were structurally weaker than forecasted for several years, the response to such a surprising development would be strongly delayed. This may undermine trust in sound public finances.

Control accounts can be an important addition to expenditure rules but also to fiscal rules in general. Budget objectives may be missed for a variety of reasons: Revenue forecasts may have been too high or too low, or spending may have been higher or lower than the authorised levels. This becomes problematic when, as a result, debt develops over time less favourably than the upper limits were designed to permit. It would therefore make sense to establish a control account. This account would record the amounts by which budget objectives have been exceeded or undershot. At the same time, a control account threshold for negative deviations from the target should be established. It should indicate when the cumulative impact on debt needs to be corrected. If the amounts recorded more or less cancel each other out over time, there would be no need for action. However, if the threshold were to be exceeded, the accumulated shortfall would have to be offset, in a rules-based manner, in the next few years. In this case, the requirements for the annual budget objective would have to be more ambitious for a certain period of time. Control accounts may also record cyclical components in order to prevent a debt increasing impact from a systematic bias.

The quantitative requirements of the European fiscal rules are sometimes criticised for being too narrow. This would become even more important if their implementation were to be tightened. Critics argue, for instance, that Member States are regularly forced to carry out procyclical consolidation in the event of an unexpected structural downturn. There are also calls for greater leeway to be provided for an active stabilisation policy.

Pre-funded national rainy day funds could address this criticism without jeopardising debt reduction. The basic idea behind this type of fund is to build up a financial buffer in good times in order to prepare for “rainy days”. This concept could be added to the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) without permitting additional debt. The targeted upper ceiling for the debt path under the MTO should still be adhered to. Therefore, it should be possible to add assets to the fund only to the amount by which the MTO is overachieved. This reserve could then allow room for manoeuvre. The limit of the regular MTO could be exceeded at a later date by drawing on these funds. As a result, the regular MTO would not be met in every single year but on average from the time the rainy day fund is established. The concept of a rainy day fund builds on front-loading and, therefore, borrowing should not be allowed.

Such funds could, in principle, be used for different purposes. However, it would be highly advisable to stipulate provisions for a rule-based use of such funds in national legislation.3 Otherwise, funds risk creating new problems: For instance, existing reserves might be used to generate “political business cycles”. To avoid these problems, provisions could specify that the funds would be reserved for cushioning unexpected budgetary burdens. Drawing on the funds would then allow the adjustments to be spread over a longer period of time.

Rainy day funds should be organised at the national level. There are calls for the introduction of a European rainy day fund, which would be jointly (and possibly debt) financed. Its proponents often stress that additional borrowing opportunities and transfers between Member States are to be ruled out by the design of the fund. However, if this were indeed to be ruled out, the stated objectives of such a European fund could be achieved in a much more straightforward and transparent way using national rainy day funds. For example, national funds do not require complicated “claw-back” mechanisms to avoid permanent transfers between Member States. Debt-financed European funds including transfers between Member States would, first, risk eroding the fiscal rules if debt is no longer recorded in the national accounts. The debt burden does not disappear by shifting it to the European level. Second, an automatic transfer mechanism between member states seems not to fit well in the current design of the monetary union. Given that the Member States are responsible for their own fiscal and economic policies, national solutions appear more appropriate.

In the debate about budget rules, there are calls to allow borrowing to finance government investment expenditure (known as the “golden rule”). The European fiscal rules make no provision for this.

On the one hand, arguments in favour of a golden rule include the following:

On the other hand, arguments against include:

The arguments in favour of a golden rule are substantial and of relevance. But, the drawbacks – not least experienced in the past – are important as well and risk outweighing the potential benefits. The problems associated with a golden rule resulted in European fiscal rules avoiding such provisions. Placing a limit on government debt was seen as a priority.

Nevertheless, if the outcome of the current European debate is that the potential benefits outweigh the concerns, it would be crucial to narrow the risks down as much as possible. Four guiding principles would be advisable.

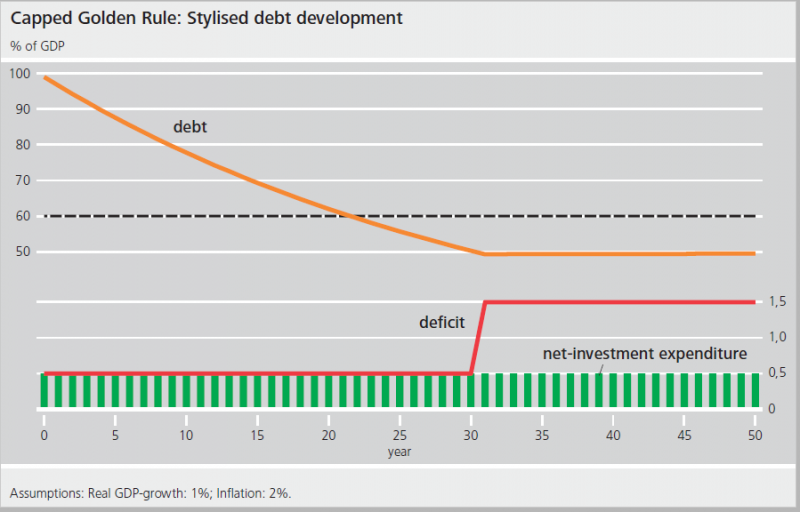

As a result, a golden rule could be based on the existing limits for the MTO and build in net investment. The rules allow a structural deficit of up to 0.5% of GDP provided that the debt ratio is not “significantly below 60%”. A debt ratio of 50% or below could be considered significantly below 60% and appears to be quite a sound basis for easing the 0.5% provision.

A capped golden rule could be designed as follows:

For debt ratios above 50% (i.e. not significantly below 60%):

For debt ratios significantly below 60% (50%), the MTO could be set less ambitiously.

Investment could also be factored into the adjustment path towards the MTO.

Such a design of a strict capped golden rule would ensure that very high and high debt ratios decline swiftly, given adherence with the rules. This cap would also limit the risks arising from undesirable interpretations and over-investment.

At the same time, this would counteract incentives to make excessive cuts to investment in order to comply with the European fiscal rules. Countries would be unable to comply with the fiscal rules by reducing investment expenditure to below 0.5% of GDP. Even where there is a need for structural adjustment, government investment would, at most, face limited consolidation pressure. At the same time, higher government net investment would still be possible, but it would not be permissible to finance it by additional borrowing.

There is a need for reform of the fiscal rules to ensure that high debt ratios fall swiftly. The way in which the European fiscal rules have evolved is unsatisfactory. Fiscal surveillance is insufficient. Even for highly indebted countries and in normal times, instances of structural loosening seem to be in line with the rules. In order to ensure a swift reduction of high public debt, the medium-term objective of the structurally (close to) balanced budget should be more binding on fiscal policymakers. Numerous exceptions and discretionary scope should therefore be dispensed with.

Limits must be implemented strictly. National parliaments remain responsible for setting fiscal policy, but the pressure to adopt a sound stance could be increased. Progress in this direction could be expected if fiscal surveillance were to be transferred to a clearly focused independent institution. Its work could be facilitated by an expenditure rule. For each fiscal year, the expenditure ceiling would be newly derived from the current, rule-compliant structural balance or the requested improvement in the structural balance. The expenditure ceiling would then be relevant with regard to the assessment of compliance with the rule. Multi-annual expenditure ceilings are not advisable.

There are ways to address calls for greater flexibility without compromising on the objective of sound public finances. In order to obtain room for manoeuvre in unexpected structural downturns, national rainy day funds could be established. They could create flexibility for fiscal policymakers, even if quantitative objectives were more stringent. The funds would be stocked in advance from overachieving the medium-term objective (MTO) and should not create additional scope for borrowing.

If the European rulebook were to move in the direction of greater protection for government investment, it should be cautiously designed: i) no compromises should be made on the objective of rapidly declining high debt ratios; ii) the rules should refer to stringently defined net investment; iii) additional debt should only be allowed for positive net investment and the amount of additional debt should be capped (capped golden rule); and iv) capital depletion (negative net investment) should call for a more ambitious fiscal position. For debt ratios significantly below 60%, positive net investment could permit some additional deficits compared to current limits. As a result, investment would be protected (in line with the calls made by the proponents of a golden rule), but not at the cost of reducing the scope for sound public finances.

Each Member State in the monetary union decides its own fiscal policy and hence – as long as this remains unchanged – must be responsible for its repercussions. Quite apart from the specific fiscal rules, each Member State decides whether or not to comply with the joint agreements and uphold them. The European level cannot enforce limits or ensure that debts are serviced. This means that individually liable financing on the capital market has to remain a key element of the monetary union. Potentially increasing risk premia still constitute a material incentive to run a sound fiscal policy. Targeted fiscal rules that are perceived to be binding can play a crucial role in creating and maintaining trust. But to do so, they have to be implemented in an appropriate manner, and compliance must be reviewed transparently and sanctioned if and when required.

This article contains substantial elements of a Monthly Report article published by the Deutsche Bundesbank in April 2019 (“European Stability and Growth Pact: individual reform options” ). However, the approach taken and the views expressed here are the sole responsibility of the author.

See, for example, the ECB in its economic bulletin 2/2019, Interest rate-growth differential and government debt dynamics, or ECB, Government debt reduction strategies in the euro area, Economic Bulletin, 3/2016 or Fuest and Gros, Government debt in times of low interest rates: the case of Europe, EconPol Policy Brief, 16/2019, March 2019, Vol. 3.

For suitable provisions in Germany, see Deutsche Bundesbank, Excursus: the use of reserves and off-budget entities by central and state government, Monthly Report, August 2018, pp. 69-73.

For example, given a structural deficit ratio of 1.5% and nominal GDP growth of 3%, the debt ratio would remain at around 50% (schematic view, without including deficit debt adjustments). Based on assumptions that would appear to be plausible, the government capital stock could converge to a size of around 50% of GDP given net investment of 0.5% of GDP.