Speech held by Agustin Carstens, General Manager, Bank for International Settlements, at Columbia University, New York, 17 April 2023.

For the first time in decades, high inflation and financial stress have emerged in tandem. They each have their own specific causes, but together they signal that the boundaries of monetary and fiscal policy’s “region of stability” are being tested. The approach to the region’s boundaries is visible across a number of dimensions: large fiscal deficits, high public debt and central bank balance sheets, together with the historically and persistently low interest rates that prevailed before the inflationary surge. These policy settings are the result of a decades-long journey where sequential policy decisions, often in response to crises, have progressively driven debt levels up and interest rates down. At each step, the policy choices seemed reasonable, even compelling. But cumulatively, they have brought us to an extraordinarily complex place where the risks to macroeconomic and financial stability loom large and the tensions between monetary and fiscal policies are growing. A shift in policy mindset is called for. Policymakers must acknowledge the limitations of stabilisation policies and they need to leave room for policy manoeuvre over time. Only by doing so can authorities preserve trust in government policies and ultimately in the key functions of the state.

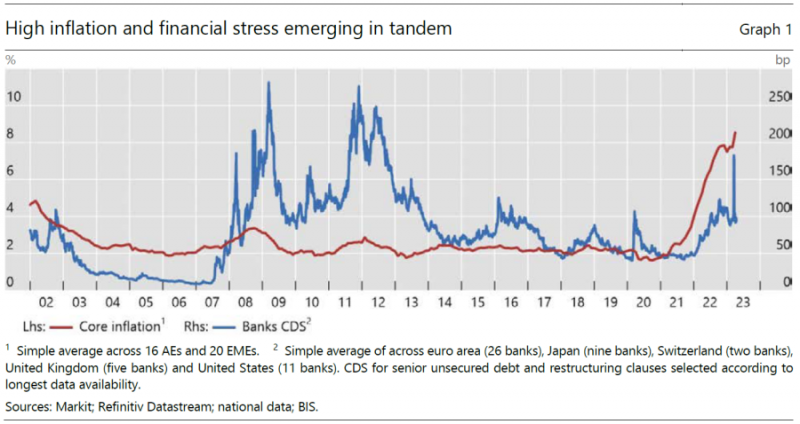

We are living in extraordinary times … once again. Over the past two years inflation has surged (Graph 1). Its rise has been large, sudden and global. In many parts of the world, it is now at levels unseen for generations. Meanwhile, financial systems have come under strain. Recent bank failures are the most prominent example, but far from the only one. For the first time in recent decades, we are seeing high inflation and financial stress emerging in tandem (Graph 1).

High inflation and financial stress each have their own specific immediate causes. But, in my view, they are a symptom of a broader and deeper problem. Monetary and fiscal policy have tested the boundaries of what I call the “region of stability”.

This region refers to the constellations of monetary and fiscal policy that, conducted over time, support macroeconomic and financial stability and keep the inevitable tensions between the two policies manageable. Staying clearly within this region prevents them from damaging the economy through inflation, financial stress and slumps. And it allows them sufficient headroom to deal with unexpected shocks that can cripple the economy and, in the process, the policies themselves.

The region’s boundaries are elusive. They cannot be summed up in simple metrics, like a limit for the ratio of public debt to GDP or the policy interest rate. The region evolves over time, influenced by long-run political and technological forces that shape the structure of production and finance. Macroeconomic policy settings can themselves alter the region’s boundaries, if kept in place for long enough.

The recent challenge to the boundaries is the latest in a long journey that stretches back at least to the 1970s. At each step, the policy choices seemed reasonable, even compelling. But cumulatively, they have brought us to an extraordinarily complex place. This reminds us that economic systems can appear stable until, suddenly, they are not. Challenges to the boundaries of the region may become fully apparent only ex post.

Let me explain.

Powerful secular tailwinds such as globalisation masked what had once served as a key signal that policies were testing the region’s limits – high inflation. The dynamics of financial liberalisation gave rise to a new signal – financial instability. Quiescent inflation fostered the belief that monetary and fiscal policy could smooth out every economic downturn and prolong expansions with little constraint. Strong stimulus was deployed in recessions but there was little normalisation and rebuilding of policy buffers when growth resumed. The pattern became starker after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and the pandemic-induced recession when extreme uncertainty prevailed, economic activity collapsed, and inflation hovered stubbornly below target.

Given the circumstances, it seemed natural that authorities could use their policies to promote growth without stoking inflation. But their ability to do so relied on aggregate supply adapting smoothly to changes in aggregate demand. This was the case for some time, but when the Covid pandemic rendered supply conditions unusually inflexible, the magnitude of the risks that were unknowingly taken became all too apparent.

Thus, a shift in policy mindset is called for. Returning firmly inside the boundaries of the region of stability should be a conscious and explicit policy consideration.

Let me elaborate on these thoughts. First, on the roles that fiscal and monetary policies have played in causing and addressing the immediate challenges of inflation and financial instability. And second, on the forces that led policymakers, at various times in the past, to approach the boundaries of the “region of stability”. I will then conclude with some reflections on how we could return to a more comfortable location within the region.

The first major challenge policymakers face is high inflation.

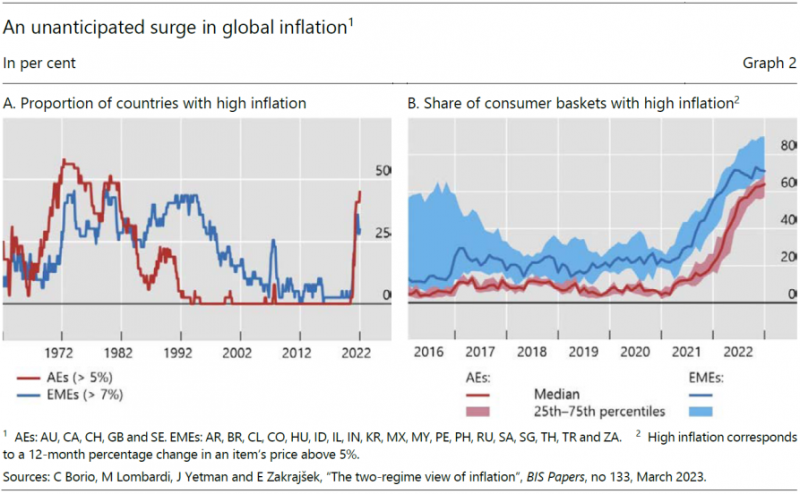

It has been almost two years since inflation returned with a vengeance. It remains much too high and has become widely entrenched across countries and sectors (Graph 2). It is increasingly clear that inflation will not come down by itself.

The causes of high inflation have been well documented. The pandemic disrupted supply chains for manufactured goods. The sudden jump in spending after restrictions lifted drove a rebound in demand for those goods. The war in Ukraine then sent commodity prices soaring.

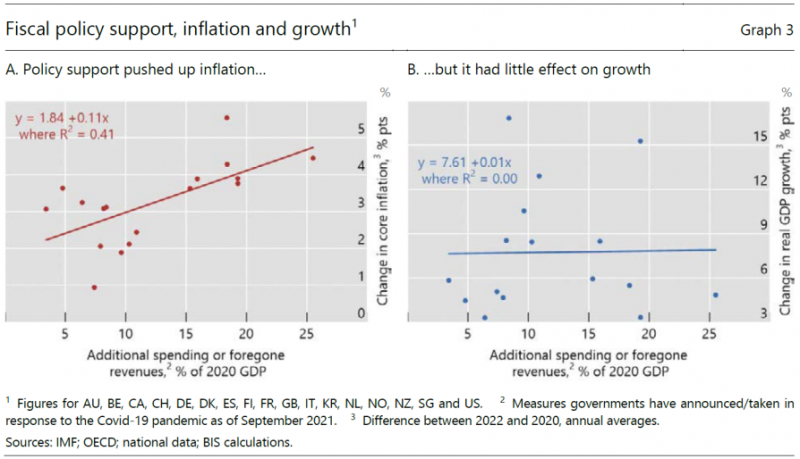

These forces were powerful. But the monetary and fiscal policy stimulus deployed during the pandemic gave inflation an even larger, and certainly more enduring, unexpected push. As a reminder, policy interest rates were lowered to zero, and often below. Central bank balance sheets ballooned. Fiscal stimulus since the start of the pandemic has exceeded 10% of GDP in many advanced economies – a push previously seen only in wartime. In many countries, households received large transfers, which in some cases exceeded the income hit from the pandemic. Firms benefited from generous subsidies to keep unutilised workers on the payroll; their debts were guaranteed. Because these measures added to demand at a time when supply was artificially constrained, they boosted inflation but did little for growth (Graph 3). The stimulus continued, and in some cases grew, long after economies started to recover.

Let me be clear: the policy responses to the pandemic were fully justified at the time. They kept firms afloat and preserved livelihoods. And they prevented economies from falling into a tailspin. In unprecedented circumstances, policymakers took no chances. But calibrating the stimulus was extremely difficult in this environment. With the benefit of hindsight, it is now clear that policy support was too large, too broad and too long-lasting.

At first, most observers – including central banks – expected higher inflation to be transitory. After all, economies had seen many inflationary spikes in recent decades – often driven by higher oil prices – and inflation had always come back down. And some of it was transitory. The prices of oil, used cars and shipping are all much lower now than a year ago. In much of the world, inflation has taken a step down from the peaks reached late last year.

Nonetheless, the next phase of the disinflationary journey is tougher. The easy gains from smoothly functioning global supply chains, lower commodity prices and base effects have largely been banked. Services, where prices are stickier, have become the main force behind inflation. Labour markets are still tight. Growth may need to slow considerably more for monetary policy to gain traction.

There is no time to lose. The longer inflation lasts, the more likely is a shift to a high-inflation regime.1 Households and firms start paying much more attention to inflation: they didn’t need to in the days of price stability. An inflationary psychology takes hold. Inflation expectations become de-anchored. The genie gets out of the bottle. The costs of regaining price stability grow. Public support wavers for travelling the last mile required to return inflation to target.

Interest rates may need to stay higher and for longer than previously thought.

If they do, governments will feel the pinch. In much of the world, public debt rose steadily as a share of GDP post-GFC, even when growth was strong. The Covid-era stimulus has raised debt further, and the cost of servicing that debt is now rising rapidly. Meanwhile, monetary policy-induced lower growth rates will increasingly strain public finances.

Weaker fiscal positions could complicate central banks’ efforts to lower inflation.

In the near term, fiscal stimulus raises inflation, partly undoing the effects of tighter monetary policy. And we should take no comfort in the fact that higher inflation has helped lower public debt-to-GDP ratios. These drops do not provide exploitable fiscal space. Indeed, the IMF expects public debt levels in both advanced and emerging market economies to resume their upward march shortly and to return to their pandemic-era highs by 2028. Moreover, because persistent inflation calls for higher interest rates, it makes current high public debt levels less sustainable.

Over the longer term, central banks may come under pressure to slow the pace of monetary tightening to ease the burden on public finances. And even where higher interest rates are manageable, central banks may face political calls to take the foot off the brake or raise the inflation target. Large central bank losses, resulting in smaller transfers to the government, are adding to the pressures. These risks are material.

The second major challenge policymakers face is financial instability.

Our outsized, fast-paced and ultra-sophisticated financial system is a fragile one. Excess leverage and liquidity mismatches lurk in unsuspected quarters or even in plain sight. Financial institutions and markets, including banks and non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs), tend to stretch each other to the limit with uncanny regularity. As the edge approaches and confidence suddenly evaporates, tremors start to be felt. Wherever the boundaries of stability may lie, this type of financial system blurs their contours.

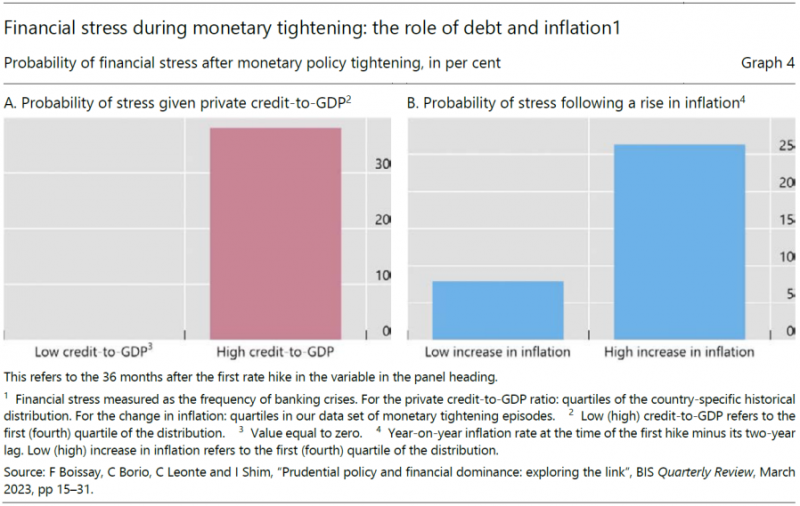

Over the past year, we have once again seen signs of stress. This is no surprise. Since the 1970s, banking stress has broken out, in close to one fifth of cases, within three years of a start on policy tightening. Larger increases in inflation and higher levels of private sector debt make stress more likely (Graph 4). Now, for the first time since the Second World War, very high levels of private debt have coincided with a surge in inflation. And all this has transpired after an unusually long phase of aggressive risk-taking in financial markets.

In some recent episodes of financial stress, it is hard to miss the footprint of the cumulative impact of monetary and fiscal policies. The root cause of these episodes has been the combination of high and rising public debt coupled with low-for-long interest rates.

For over a decade, many sovereigns issued outsize amounts of debt at very low interest rates and long duration. The bulk was absorbed by financial intermediaries. These intermediaries – notably banks, investment funds, insurance companies, pension funds and hedge funds – became exposed to the risk of higher interest rates. The expectation that interest rates would stay low shaped business models, fuelled risk-taking and encouraged leverage. It promoted aggressive maturity transformation and liquidity mismatches, thereby amplifying the potential for financial stress.

Consider two recent instances.

Silicon Valley Bank went under because its largely uninsured and concentrated depositor base woke up to high unrealised losses on long-duration, mostly government, securities. A classic depositor run and liquidity squeeze forced recognition of these losses. This triggered broader contagion across medium-sized US regional banks.

In the turmoil engulfing UK defined benefit pension funds last year, the problems originated from hedges against further declines in interest rates implemented through leveraged funds – so-called liability-driven investment (LDI) strategies. As monetary policy was tightening, an unexpected announcement putting fiscal policy credibility on the line drove yields up. As a result, the hedges generated heavy losses that threatened the solvency of the investment vehicles and generated a liquidity squeeze. This triggered forced selling of government paper in a falling market. The hedges protected the solvency of the pension funds but not that of the vehicles in which they had invested.

While, in the UK episode, concerns about the fiscal position caused localised stress, the damage can be much larger. Acute doubts about sovereign creditworthiness can destabilise the whole financial system through the so-called sovereign-bank doom loop. The loop is set in motion when banks’ exposures to the sovereign put institutions’ viability in doubt. Episodes of this kind have been more common in emerging market economies. But advanced economies have not been entirely spared. Recall the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area. Higher interest rates naturally heighten this risk.

The direction of causality can also run the other way. Financial crises can wreak havoc on fiscal accounts and endanger fiscal sustainability. Even as the economy tanks, sapping tax revenue, the sovereign has to step in as the financial system’s ultimate backstop. Central banks can provide liquidity, but only the government can address solvency. Past crises have shown that the fiscal costs can be very large.2

The risk of financial instability heightens the challenges that central banks face as they seek to restore price stability. The risk would be larger should central banks have to keep interest rates higher for longer. Substantial additional tightening could trigger renewed financial turmoil. And financial turmoil may require them to intervene to stabilise the financial system, in their capacity of lenders or market-makers of last resort. They have done so more than once in recent years. No wonder some observers have raised the concern that central banks might give up on their efforts to bring inflation under control – so-called “financial dominance”. I do not particularly like the term, as it implies that central banks are not following their mandates and are dominated by outside forces. This would be a mistake. I will come back to this point when elaborating on the way forward.

Let’s now look at the bigger picture to better understand how we got here. Where did the two policies find themselves before the inflation surge? In what sense were they testing the boundaries of the region of stability? And how did they get there?

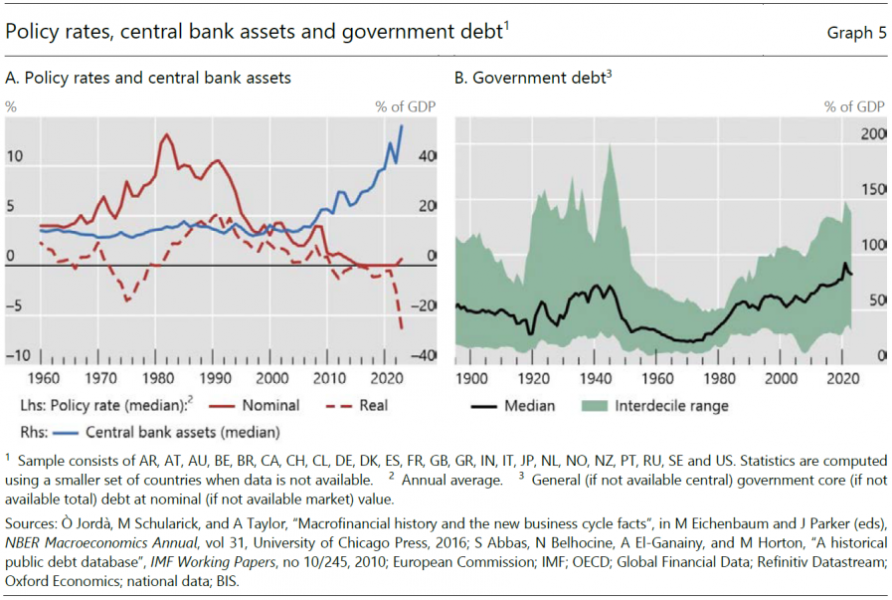

Monetary and fiscal policies were in an extraordinary place before the inflation surge (Graph 5). Nominal interest rates were at record lows. Real interest rates had never been negative for so long. Meanwhile, central bank balance sheets and public debt were approaching record highs. This configuration was historically unprecedented.

These were symptoms that the two policies were testing the boundaries of the region of stability. They also illustrate how navigating the region involves fundamental intertemporal trade-offs. Policy settings that appear stabilising and compelling in the near term can, if maintained for long enough, generate instability down the road. It is not the month-to-month policy choices that matter, but their trajectory and cumulative impact. What policymakers may take as given at any point in time – as part of the landscape, as it were – can be, to a material extent, the result of past decisions. Things may even appear stable for a long time until, suddenly, they are not. At that point, the disruptive force of the hidden accumulated vulnerabilities surfaces with a vengeance. All this makes the region’s boundaries hard to pinpoint in real time, as they expand and shrink with the evolution of the economy and the financial system.

Indeed, the configuration of monetary and fiscal policies appeared surprisingly stable before the inflation surge. The perception of a new normal had a certain allure. However, monetary and fiscal policy had gradually lost room for policy manoeuvre, and worryingly so. To be sure, as the effective response to the Covid-19 crisis shows, they could still do more. But only at the cost of stretching conditions further. This left the economy even more exposed to future shocks and raised the risk that the policy settings could generate further vulnerabilities.

Over time, policies would have needed to regain policy headroom; but in the process they would have worked at cross-purposes. Higher interest rates would make fiscal consolidation harder; fiscal consolidation would put pressure on monetary policy to remain easy for longer if growth remained subdued.

What we have seen in the pandemic’s aftermath is just one of the possible manifestations of this inevitable tension.

The journey to the boundaries of the region of stability on the eve of the recent inflation surge was not linear. The symptoms of an overly expansive policy stance evolved with the economic landscape that those policies were helping to shape together with more fundamental, structural forces. A consistent factor in all this was the overestimation of how far macroeconomic policies could be used to steer the economy and, by pushing hard enough, ignite the engine of long-term growth – this is what I call the “growth illusion”. Let me explain.

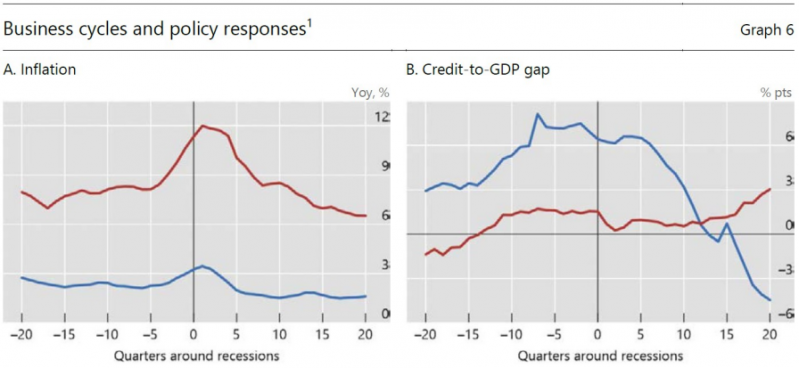

We can divide the period going back to the 1960s into two phases, with the mid-1980s as a rough watershed (Graph 6).

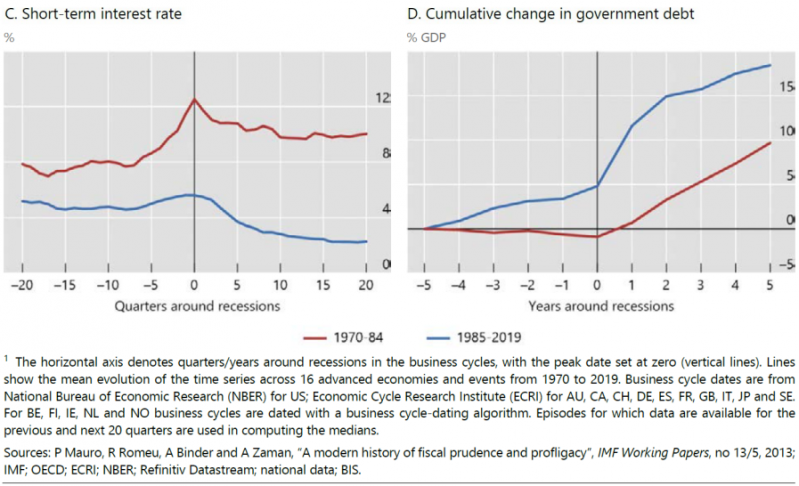

In the first phase, let’s say from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s, surging inflation was the red flag, signalling that policies had overstepped the boundaries of the region of stability. Recessions were typically triggered when monetary policy was tightened to tame inflation. Simplifying somewhat, the intellectual backdrop was the belief that policymakers could fine-tune the economy by a carefully calibrated mix of monetary and fiscal policy. Hence the concept of a stable long-run trade-off between unemployment and inflation. The result was the Great Inflation of the 1970s.

In response to the inflation crisis, policymakers took steps to bring monetary and fiscal policies back clearly within the region of stability. Central banks sought to end inflation for good by aggressively hiking policy rates. Following the disinflation in the first half of the 1980s, monetary regimes prioritising price stability gradually became the norm. Interest rates declined substantially from their previous peak. However, the rise in interest rates on the back of monetary tightening in the early 1980s had exposed fiscal fragilities. In combination with persistent fiscal deficits, this led to a surge in public debt. Thus, many governments were forced to embark on fiscal consolidation and take a step back within the region of stability. For more than a decade from the early 1990s, public debt levels, on average, stabilised.

In the second phase, say from the late 1980s to the eve of the pandemic, changing macroeconomic policy frameworks went hand in hand with fundamental structural change. Financial systems were profoundly liberalised. By the early 1990s, a “government-led” financial system had given way to a “market-led” one, both domestically and internationally.3 The globalisation of the real economy followed. Emerging market economies, China most notably, joined a seamless global labour force; tight production networks spread across the world.

Against this backdrop, the nature of the business cycle changed equally fundamentally. Inflation ceased to be the main symptom that policies were testing the limits of an economic expansion. Central banks were doing their job and the globalisation of the real economy was eroding the pricing power of workers and firms. These were powerful tailwinds that helped central banks hardwire the low-inflation regime. The symptoms of overstretch now took the form of financial imbalances. Inflation-induced recessions gave way to financial recessions. Financial cycles became larger and more disruptive, culminating in the GFC. Financial liberalisation had provided fertile conditions.

Over time, the shift from inflationary imbalances to financial imbalances contributed to the gradual erosion in policy space. Monetary policy eased during contractions to cushion the economy and fight the headwinds of private-sector balance sheet repair. But it had little reason to tighten much during expansions since inflation remained low and stable. Interest rates progressively declined. For fiscal policy, the GFC was a watershed. Financial crises forced sovereigns to backstop the financial system and support faltering economies. Public debt increased massively, sustained by low interest rates that kept a lid on debt servicing costs.

The challenges intensified in the aftermath of the GFC. Monetary policy struggled to push inflation back up to target: the globalisation tailwinds that had helped to bring inflation down to target pre-GFC were hindering the central bank’s efforts to push it back up. As fiscal policy sought to regain some of the room for manoeuvre lost in the aftermath of the GFC, monetary policy became the “only game in town”. As time wore on, fiscal policy was then asked to give a helping hand. It was a topsy-turvy world compared with the one that had preceded it.

And then the pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine struck.

What does this analysis mean for policy? Let me sketch a broad direction of travel.

The near-term challenge is to restore price stability. This is the priority. At the same time, central banks will need to address any further financial strains that might emerge. If a high-inflation regime sets in, the costs to price and financial stability will be too high. There will be a premium on differentiating measures designed to achieve the two objectives. It will be important to ensure that the tightening path consistent with lower inflation is not compromised by the immediate needs of the financial sector. Fiscal policy will also have to play its part. Through consolidation, it would help to reduce pressure on aggregate demand and inflation, limit the risk of being a source of financial instability and provide more headroom should it be called upon to support crisis management by tackling solvency concerns. As monetary and fiscal policy acting in tandem bring inflation under control, financial instability should subside.

The longer-term challenge is to ensure that monetary and fiscal policies operate clearly within the region of stability on a lasting basis. This has to do with strategies, institutions and mindsets.

Policy strategies should aim to keep room for policy manoeuvre over time. This calls for more symmetrical policies over the business cycle. Arguably, there is room for monetary policy to be somewhat more tolerant of moderate, even if persistent, shortfalls of inflation from point targets once inflation settles at a low level. In a low-inflation regime, inflation has certain self-stabilising properties; as a result, the central bank can better enjoy the fruits of its hard-earned credibility. This will help to make the interest rate cycle more symmetrical. And it will also reduce the need to keep interest rates unusually low for unusually long, thereby limiting the associated side effects, most notably the build-up of financial vulnerabilities. As for fiscal policy, when assessing fiscal space, it would be important to account for the flattering effect of financial booms on the fiscal accounts and the possible costs of financial stress.

To expand the room for manoeuvre of monetary and fiscal policy, it is essential to complement them with a sound micro- and macro-prudential framework. A lot has been done following the GFC to strengthen the financial system. That said, progress has been uneven. It has made good progress in the banking sector but has lagged behind in the NBFI one, which in the meantime has grown in leaps and bounds. Moreover, recent strains in the banking sector indicate that there is still work to do there as well.

Beyond adjustments to monetary and fiscal policy strategies, institutional safeguards are necessary to limit tensions between the two policies and promote their coherence. Central bank independence remains key. Mechanisms to encourage prudent fiscal policy, such as independent fiscal councils and well designed fiscal rules, should be given greater bite.

Ultimately, though, what matters most is mindsets. Policy adjustments require the limitations of macroeconomic stabilisation policies to be acknowledged. Those policies can be a major force for good, but, if overly ambitious, can also cause great damage. The journey I have described shows that, if the specific challenges evolve with the economic landscape, the root cause of failures does not. The fallacies of the “growth illusion” teach us that, to generate resilient and sustainable growth, there is no alternative to working on the supply side of the economy.4 Structural reforms are politically difficult, we know; but we also know that there is no free lunch. The region of stability concept, hard as it may be to apply in real time, embodies the recognition of the limitations of macroeconomic policies. The region is not a number, or even a set of numbers, but a way of looking at the world and guiding policy. It can help preserve the all-important trust that society must have in the state and its decision-making.

See “Inflation: a look under the hood”, Chapter II, BIS Annual Economic Report, June 2022 and C Borio, M Lombardi, J Yetman and E Zakrajšek,“The two-regime view of inflation”, BIS Papers, no 133, March 2023.

For an in-depth overview of the link between fiscal policy and financial stability, see C Borio, M Farag and F Zampolli, “Tackling the fiscal policy–financial stability nexus”, BIS Working Papers, no 1090, April 2023.

T Padoa-Schioppa and F Saccomanni “Managing a market-led global financial system” in Managing the global economy: fifty years after Bretton Woods, Institute of International Finance, Washington DC, 1994, pp 235–68.

See A Carstens, “A story of tailwinds and headwinds: aggregate supply and macroeconomic stabilisation”, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, 26 August 2022.