The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Fiscal Board or the European Commission.

The ongoing debate that seeks to reform the EU’s fiscal framework is characterised by two opposing perspectives. Those who point to the lacklustre compliance of some member states with current fiscal rules calling for a more stringent practice intent on reducing risks at the national level. And those who emphasise the lack of public risk sharing at the EU level arguing in favour of a central fiscal capacity. Against this backdrop, this brief lays out the evolution and performance of the EU’s fiscal framework over the past decades in order to frame the current political negotiations of reform. It highlights an unresolved challenge for further fiscal integration: the call for more money from the centre without a compelling way to strengthen cooperation.

Launched in the 1990s, the EU’s fiscal framework is meant to contribute to a smooth functioning of the single currency area. Successive crisis episodes put pressure on its original design triggering a series of reforms. At inception, the framework was geared towards protecting centralised monetary policy making from the possible fall-out of unsustainable national fiscal policies. Risk reduction rather than risk sharing was the main theme embodied in the Maastricht Treaty and subsequently in the secondary legislation underpinning the SGP.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09 and the subsequent euro-area sovereign debt crisis marked a clear paradigm shift. Confronted with the perceived risk of an imploding single currency, euro-area member states opened the door to elements of risk sharing such as the establishment of the European Stability Mechanism. To appease the sceptics of risk sharing and address concerns of moral hazard, access to the new instrument was subject to strict policy conditions, and new elements of risk reduction were introduced including the Fiscal Compact1, an attempt to hardwire key elements of the EU’s fiscal framework into national law. The Covid-19 pandemic has brought further instruments of risk sharing, most notably the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), albeit of a temporary nature. The introduction of new elements of risk sharing and risk reduction also came at the price of blending different governance models. In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, the time-tested but very involving community-method was complemented with nimbler yet ad hoc inter-governmental elements, and new national actors, national independent fiscal institutions, were added.

The academic literature has for a very long time been converging on the view that, ideally, an economic and monetary union needs both elements of risk reduction and risk sharing, including in particular a central fiscal transfer instrument. However, the history of EU economic integration is characterised by persistent differences in economic performance and in economic resilience to shocks and the political arena remains divided about the relative importance of risk reduction and risk sharing.

In a recent paper (Larch et al., 2022) we review the performance of the EU’s fiscal framework against the backdrop of the current state of the economic governance review.

The effectiveness of the EU’s fiscal framework has typically been assessed with regard to three main dimensions: (i) the long-term sustainability of public finances, (ii) the stabilisation of aggregate demand over the cycle, and (iii) the quality of public finances.2

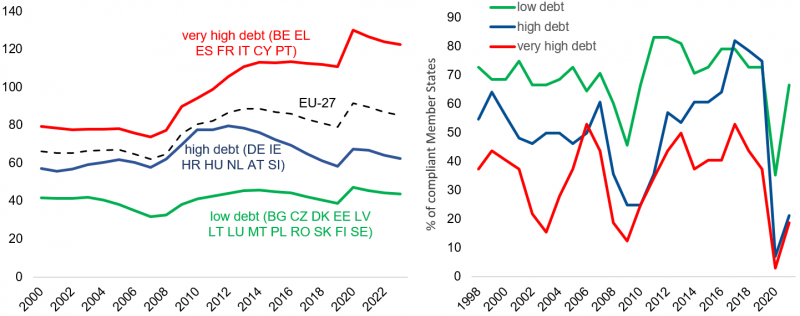

In terms of sustainability, the performance of the EU’s fiscal framework is very mixed. Countries that joined the euro with high debt levels have seen debt ratios rise further during economic downturns but did not manage to reduce them during subsequent recoveries. Following a ‘nominal strategy’, they reported automatic improvements of headline balances during economic upturns, but exhibited a much lower compliance with the structural balance and expenditure rules of the SGP (EFB, 2019). In contrast, countries that joined the single currency with lower debt levels, averted a ratcheting up effect by reversing increases of government debt during upturns. The EFB Secretariat’s compliance tracker underscores stark differences: in low debt countries, the average rate of numerical compliance with the SGP rules was 67% in 1998-2021, as opposed to 33% in countries with a very high debt (see Graph 1). Past reform efforts aimed at enhancing the relevance of the cycle in fiscal guidance have not been able to break the diverging pattern across the two groups.

Graph 1: Government debt to GDP ratios and compliance record across country groups

Note: Countries are grouped by their average debt-to-GDP ratio over 2011-2019: (1) Very high-debt countries = above 90% of GDP (Belgium, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal); (2) High-debt countries = between 60% and 90% of GDP (Germany, Ireland, Croatia, Hungary, The Netherlands, Austria, Slovenia); (3) Low-debt countries = below 60% (Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden).

Source: European Commission, Compliance tracker of the EFB secretariat, own calculations.

In fact, the stabilisation properties of national fiscal policies have not improved across the board. Admittedly, there were clear episodes of counter-cyclical expansions under the SGP, especially in the wake of large negative shocks. However, countries performed much more heterogeneously during economic recoveries. Some achieved counter-cyclical tightening by building buffers, but many very-high-debt countries failed to take advantage of improving economic conditions.

It is also worth stressing that the experience of EU member states does not corroborate the claim according to which pro-cyclical fiscal policies can be attributed to the limits imposed by EU fiscal rules. Over the past several decades pro-cyclical fiscal episodes have been as frequent outside the EU as they were in EU member states (Larch et al. 2020). Rather, political economy issues remain strong, especially in economic good times. If all member states had stuck to the commitments under the SGP, stabilisation policies would have been more effective (see e.g. Gootjes and De Haan 2022).

The quality of public finances has generally played a secondary role in the EU’s fiscal framework. Some tools to promote public investment have been added to the SGP, driven by the notion that a shift in the allocation of expenditure towards government investment would have a growth-enhancing effect. Nevertheless, investment tends to be the first to fall victim of government consolidation efforts as it is politically less costly than cutting current expenditure or raise taxes. This pattern has been corroborated by the chronically anaemic public investment trends in the EU ever since the Great Financial Crisis. Empirical evidence suggests that fiscal rules have not been the constraining factor (European Commission 2022).

The mixed results of the EU’s fiscal framework characterised above corroborate a fundamental tenet of mainstream economic thinking: rational decision makers driven by self-interest will free ride on public goods and/or not internalise external effects produced by their actions. Cooperation is not the natural outcome; it requires binding contracts or outside enforcement. After all, it was this fundamental insight, together with a history of persistent differences in economic performance and resilience, which back in the early 1990s motivated the then 12 EU member states to agree on arrangements – anchored in the Maastricht Treaty and later on detailed in secondary EU legislation – aimed to avert significant spill-overs from national fiscal policies and to safeguard the effectiveness of centralised monetary policy.

While legal texts can sometimes confound motives, the most concise formulation of the underlying commitment can be found in declaration 30 of the intergovernmental conference which adopted the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007. It includes the following two plain sentences: “The conference reaffirms its commitment to the provisions of the Stability and Growth Pact as the framework for the coordination of the budgetary policies in the Member States. The conference confirms that a rules-based system is the best guarantee for commitments to be enforced and for all Member States to be treated equally.“

The declaration, which echoes concepts laid out in the Council resolution of 1997 heralding the entry into force of the SGP, emphasises the idea of an even-handed implementation of a commonly-agreed, rules-based system: in essence, cooperation through reciprocity and enforcement.

However, while built on the right premises, today the prevailing perception is that the SGP did not live up to its original expectations, at least not in all parts of the Union. The basic truth encapsulated in the popular notion that governments have no friends only interests, clearly overshadowed solemn declarations. As a result, today views continue to diverge about how to revisit the EU’s fiscal framework. The ongoing economic governance review – the official assessment process at the EU level launched at the beginning of 2020 – testifies to the difficulty of finding consensus.

To start with, many observers tend to generalise when it comes to the performance of the EU’s fiscal framework suggesting the SGP has not worked across the board. As highlighted above, such a generalisation does not reflect reality. A majority of EU member states has followed a course of fiscal policy which, even if not always compliant with the letter of the SGP every year, entails a virtuous path of public finances. Other countries, by contrast, followed an asymmetric approach: they let government debt increase during difficult times, but did not manage to bring it back down during upturns. Hence, the rules seem to have worked for most countries but not for all. Obviously, in a single currency area with highly integrated economies serious problems in one country can rock the whole boat.

While the spectrum of views is wide, it is characterised by two opposing schools of thought. The dispute is around the fundamental question of how to ensure cooperation among national fiscal policy makers in a single currency area. On one side of the spectrum, there are those who insist the commonly agreed rules are basically fine, they can be implemented with the right amount of flexibility and enforced properly, possibly through more automaticity. In clear contrast, the rival school of thought argues that in a multilateral context such as the EU, enforcement of rules will never work and that the only way to achieve any degree of buy-in from national governments is to adjust rules to national needs and preferences and to absorb spill-over risks with a central fiscal capacity.

As is often the case with opposing views, both sides make some valid and some less valid points. Those insisting on enforcement do not want to accept the plain fact that although sanctions under the SGP have formally been strengthened and widened over the course of successive reforms, they have never been applied. Of course, sanctions are meant to have a dissuasive effect ideally discouraging member states from deviating from the course of fiscal policy implied by the commonly agreed rules. Hence, a history without recourse to sanctions under the SGP may not necessarily be a bad sign. However, in combination with a dismal compliance record in some EU member states, which over time ended up accumulating very high levels of government debt relative to GDP, it certainly is.

The truth is that albeit formally empowered, the Council never found the necessary majority to apply the sanctions laid down in the commonly agreed fiscal rule. However, enforcement of EU fiscal rules can also be strengthened through links with other EU policy instruments. Conditionality under the EU’s cohesion policy, which absorbs a very large relative share in the budget of the Union, is a prime example. Relevant EU law includes provisions of macroeconomic conditionality, which have been extended and strengthened over time. They oblige the Commission to propose the suspension of several European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) in case of non-effective action under the EDP.

Those disputing the viability of any kind of enforcement and insisting on bespoke commitments, possibly negotiated individually for each country, underestimate the importance of reciprocity. The resolution of 1997 mentioned above may not produce any legal effects, but it highlights a crucial point that has been consistently present in the implementation of the SGP since inception: a rules-based system aimed at equal treatment. The coordination of national fiscal policies can only be effective if its application across member states is perceived as fair. If discretion trumps rules and some members consistently get away with a more lenient treatment than others, the overall commitment to cooperate weakens.

Since there are no free lunches, we are currently faced with the price of the very uneven SGP compliance. The central monetary authority is confronted with a trade-off that it has tried to avoid since inception: price stability versus integrity of the single currency area. To be clear, the strong surge of consumer price inflation in the euro area in 2022 is mostly caused by the energy crisis linked to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, less by recent expansionary fiscal policies. However, if all euro-area member states had kept debt-to-GDP ratios at medium or low levels, the ECB and the member states would have had much more policy space to fight the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the latest terms-of-trade shock ensuing from energy price hikes.

The ingenuous solution envisaged by those who question the viability of enforcing common rules through peers is to call for a permanent fiscal stabilisation capacity aimed at absorbing large common or idiosyncratic shocks. Allocating more power to the central level would be the most extreme form of enforcement involving the loss of national sovereignty. However, it is probably no coincidence that most proposals advocating a permanent central fiscal capacity are not very specific about governance. They seem to be predicated on the assumption that a central fiscal capacity can be established at unchanged governance. In other words, the EU simply gets access to more resources to be distributed in some way, while national governments and parliaments maintain current fiscal policy prerogatives including the freedom to free ride.

Would such an innovation solve current challenges and lead to a politically stable solution? In all likelihood not. To be clear, ever since Mundell formulated the theory of optimal currency areas in the 1960s, we know that a central fiscal transfer mechanism should be part and parcel of a single currency area. But we also know that achieving the common sense of political purpose and the political majorities needed to establish a fiscal transfer mechanism is very challenging.

Policy proposals intent on simply adding a permanent fiscal capacity at the EU level without flanking governance reforms do not address the underlying issue of cooperation or lack thereof. They take it for granted that rules-based cooperation will never be enforced at the level of peers and see a central fiscal instrument as the only way to stabilise the system. But there lies the catch 22: The majorities required to establish a permanent fiscal capacity to address instability, including the one stemming from insufficient cooperation, are a fairly distant prospect. At unchanged governance, the current tension between the two rival groups would simply resurface around the size, the trigger and the degree of redistribution of a permanent central fiscal capacity. Without the adequate level of political representation and accountability at the EU level, combined ideally with tighter limits on national fiscal policy discretion, a central fiscal capacity would remain a barren arrangement ultimately bound to fail. More money from the centre but no credible commitment to strengthen cooperation seems difficult to achieve.

As should have become clear by now, the fundamental disagreement about the opportunity and effectiveness of enforcement of EU fiscal rules largely overlaps with the relative importance attached to risk reduction versus risk sharing. Past reforms of the EU’s fiscal framework typically involved concessions on both sides: New elements of risk sharing or flexibility around rules came together with new elements of risks reduction. There was a clear awareness that progress can only be achieved when moving ahead on both fronts. In the current context of the economic governance review the willingness to make concessions to the other side seems limited.

By the very nature of the impasse, the two camps are both right and wrong at the same time. Insisting on a system that is not enforced may be principled but not expedient. By the same token, it is misleading to assume macro-financial stability in EMU can be safeguarded through more fiscal power at the supranational level, on the premise it would suppress entrenched conflicts of interest over the appropriate balance between risk sharing versus risk reduction without adjusting governance and accountability and without addressing ‘free-riding’.

At the time of writing, it is difficult to anticipate what the final outcome of the ongoing reform debate will be. So far, agreement has been reached on a number of principles such as simplifying the EU fiscal rules, focusing on the sustainability of public finances, ensuring a growth-friendly debt reduction, strengthening the medium-term orientation of budgetary policies and improving enforcement.

Translating these principles into a concrete reform plan is another matter. When the economic governance review was launched in early 2020, times were fairly stable and the urgency to act with a major reform correspondingly low. The Covid-19 pandemic first and the war in Ukraine after have radically changed the context amplifying pre-existing challenges and adding new ones. The current focus of EU policy makers is clearly on energy and security which generates a growing awareness that haggling over the reform of the EU’s fiscal framework should not hold back progress on more existential issues. In other words, circumstances may eventually push the two rival camps to agree on a compromise to be able to invest national and collective political capital in tackling bigger challenges.

The Commission communication of 9 November 2022 outlining orientations for a possible reform of the SGP supports this narrative.3 It charts out an evolution of the SGP, which, if agreed, would introduce significant innovations in the way the common fiscal framework is implemented, while keeping the underlying philosophy of coordination largely unchanged. In particular, it is predicated on the assumption that less demanding and more differentiated adjustment requirements will improve the willingness to cooperate.

Admittedly, the orientations also refer to the intention of applying sanctions more rigorously. However, while the proposal on how to modify adjustment requirements is very detailed, the part on sanctions is at this stage a pledge similar to those of the past. Moreover, the orientations for reform turn debt sustainability analysis into the linchpin of EU fiscal surveillance, potentially shifting the balance towards more discretion and altering the basic and original understanding of equal treatment.

The Commission communication does include a couple of references to a permanent central fiscal capacity when setting the scene for a possible reform of the economic governance framework. But the orientations proper are limited to a review of the fiscal rules. Most stakeholders seem to accept the fact that putting them together would give rise to a toxic mix heightening the persistent tensions between groups of countries and lowering chances of success.

In the final analysis, tensions can only be resolved once fiscal policy is built around a governance framework that safeguards the appropriate enforcement or political accountability at the EU level. Until now the determination to hold ‘free-riders’ accountable has been limited, as has been the appetite to establish a permanent fiscal capacity. The spectrum of possible ways forward is delimited by two scenarios: one in which enforcement is eventually achieved without major changes in EU governance; the other where fiscal cooperation is accompanied by governance reforms strengthening political responsibility and accountability at the EU level. Until then, major not self-inflicted crises affecting the stability of the euro area will be tackled by temporary EU fiscal instruments.

EFB (2019): Assessment of EU fiscal rules with a focus on the six and two-pack legislation. European Fiscal Board: Brussels

European Commission (2022): Do negative interest rate-growth differentials and fiscal rules matter for the quality of public finances? New evidence. In: Report on Public Finances in EMU 2021. Institutional Paper No. 181: 59-86.

Gootjes, B. and De Haan, J. (2022): Procyclicality of fiscal policy in European Union countries. Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 120.

Larch, M., Orseau, E., and van der Wielen, W. (2020): Do EU Fiscal Rules Support or Hinder Counter-Cyclical Fiscal Policy?. CESifo Working Paper, 8659.

Larch, M., Busse, M., Gabrijelcic, M., Jankovics L ., and Malzubris, J (2022): Assessment of the EU’s fiscal framework and the way forward: persisting tensions between risk reduction and risk sharing., Bruges European Economic Research Papers, Vol. 2022/42

The Fiscal Compact is Title III of the intergovernmental Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union, signed in March 2012. This specific part of the Treaty lays down obligations for the 19 euro area countries, while Bulgaria, Denmark and Romania are bound by the same requirements on a voluntary basis.

The Spanish version of the full paper will be published in the forthcoming issue no. 175 of Papeles de Economia Espanola.

Commission communication on orientations for a reform of the EU economic governance framework.