The Government has held a re-negotiation of our relationship with the EU that promises – at least in the short run – to make everyone worse off, less secure, and diminished in the eyes of the world. Emotionally, we have already `left’ the EU, so the pro-Europe campaign must set out a positive case to answer the question of why we want to `join’ Europe.

Whatever the result of the Third Referendum, a formal decision would then be made by Parliament within a few days to Leave OR, to revoke the Article 50 notice of intention to leave. That would end the damaging uncertainty immediately.

The EU27 has been far-sighted and given the UK a long enough postponement of Brexit for the UK to come to a settled view about what it really wants to do. Since that decision, the “will of the people” has been tested twice – though nominally on different topics.

Historical note about the 1975 referendum on Remaining in the EUThe UK joined the EU in 1973 through a vote in Parliament. MORI has provided an excellent review of opinion polls since. The bottom line is that electors soon came to the conclusion that we were wrong to have joined – by about 2:1. Harold Wilson won the February 1974 election with the promise of a referendum on EU membership BUT only after re-negotiating the deal. A year later, the polls were registering 41:33 in favour of leaving but the follow-up question was key: how would you vote if the terms were re-negotiated favourably? Opinion reversed to 50:22 in favour of staying – an 18% swing! On referendum day in June 1975, the people expressed their will very clearly: 67:33 to remain in. |

The 2019 campaign may be the opposite way round: the Government has held a re-negotiation that promises – at least in the short run – to make everyone worse off, less secure, and diminished in the eyes of the world. In 1975, the renegotiation was to be “favourable”. This time, whatever “deal” is finally agreed by Parliament to propose to the EU27, it will be seen as an “unfavourable” negotiation as the bland statements by the Leavers in 2016 are now exposed to full public scrutiny.

The people are already well aware that all is not going well with the 2016 concept of Brexit. Current polls show that only about 5% of respondents strongly approve of the Government’s handling of the negotiations but well over 40% disapprove. Will the UK get a “good deal”? Confidence in the outcome has slumped from 33% at the beginning of 2017 to only 6% now. This is a stunning decline in confidence about the outcome.

So the Leave campaigners have the difficult task of persuading the people to vote for a deal that is massively though to be bad – and by two entirely opposed camps: Many Leavers seem to want a no-deal exit – especially amongst Tory voters. So they should oppose the deal as not being Brexity enough. Many Leave voters of 2016 may become even more disillusioned the more the significance of the actual deal is explained to them.

The decisive factor may be the ability of the pro-Europe campaign to set out a positive case to answer the question of why we want to `join’ Europe – emotionally, we have already `left’. How can Europe fulfil our aspirations in policy areas where it has a say? Education, housing, roads, railways etc. are nothing to do with Europe – and Europe cannot solve these problems for us no matter how much we would like them to.

A huge weight of political and media attention has been placed on the Irish backstop. Sadly, little attention has been given to the longer-term significance of the Political Declaration on the Future Relationship (PDFR).

In the 15 months between October 2019 and December 2020, the UK and EU27 plan to negotiate an “ambitious, broad, deep and flexible partnership…” – an extraordinarily short period for such a mammoth task. After all, the Withdrawal Agreement itself has taken much longer already. UK politicians comfort themselves by repeating the (incorrect) mantra that the UK is the fifth largest economy. Very few of them have grasped that the EU27’s population is seven times the UK’ s, and its GDP is six times ours. This will not be a negotiation between equals.

The PDFR lays out the implications in plain English in its fourth paragraph: “The future relationship will be based on a balance of rights and obligations, taking into account the principles of each Party. This balance must ensure the autonomy of the Union’s decision making [author’s emphasis] and be consistent with the Union’s principles, in particular with respect to the integrity of the Single Market and the Customs Union and the indivisibility of the four freedoms”. In its 36 pages, the PDFR mentions the EU27’s autonomy of decision making no less than twelve times. The clock will surely tick down loudly on any UK attempt to negotiate away the Union’s autonomy.

The implication is quite clear: the EU27 will – indeed must – continue to develop the Single Market to maximise their own interests – with strong support from their citizens (see below). The current co-incidence of `rules’ will only persist if the UK follows, precisely, any changes they make to their rules as time goes by. Perhaps Brexiters have read the EEA/EFTA analysis of that group’s influence “Bearing in mind that the EEA EFTA States have little influence on the decision-making phase on the EU side…”. Diminutive Switzerland is well on the way to being obliged to accept a new institutional relationship with the EU that corresponds closely to this EEA model. Brexiters often refer derisively to this relative balance of powers as that of a “vassal state”. They are right about the likely negotiations on the UK/EU27 balance.2

But this is precisely what is required if the Irish backstop is not to crystallise. If it does crystallise as a hard border that undermines the Good Friday Agreement, then US House of Representatives Speaker Pelossi has recently stated forcefully that the Congress would not agree to a trade deal with the UK – no matter how much President Trump wishes.

Even if the transitional period of clearly vassal-statehood is extended, it is the current Members of Parliament who will vote on the outcome of these negotiations. Will the European Research Group (ERG) and fellow travellers accept such a permanently vassal state deal? Extremely unlikely. On current Parliamentary arithmetic, there must therefore be a high risk that this hoped-for “ambitious … partnership” will not be voted into existence in 15 months’ time. Instead, the UK will terminate its economic relationship with EU27 and move to trade on “WTO terms”.

|

Unfortunately the WTO will probably barely exist by then as President Trump will have successfully neutered the vital Appellate Body (see my European Movement blog of November 2018). Moreover, the splitting of the EU’s Tariff Rate Quotas with the UK may have been thwarted by Russian objections. |

Overall, the risks are high that Prime Minister May’s “Deal” will lead to a future EU/UK economic relationship that is “crashing out with no deal”. The only difference will be whether the private sector is caught flat-footed in October 2019 (because of its belief in Government statements) or has the time to migrate more comprehensively by December 2020. In all probability, `a’ deal agreed by Parliament will be not some nice, clean compromise Brexit but – as the Chancellor explained – it will be a catastrophic miring of the economy for years.

Moreover, Parliament may finally be persuaded to vote for “a” deal that will not be accepted by the EU27. Its peoples also have a “will” and the evidence (see below) is that they will not tolerate any unwinding of the single market that would give the UK frictionless trading access to their market.

It is now essential that any proposals agreed by Parliament are properly fleshed out as to what the proponents actually want to do, how they would achieve it and the likelihood of the EU accepting it. Wishes for a `unicorn’ that will remove all the things that people are `against’ no longer cuts the mustard. Most of these objectionable `things’ are problems at the national level and are not even a matter where the Union level can act.

It is time to get real about practical proposals as 17 million Leavers cannot be misled into thinking there is a magic, painless solution to all the nation’s ills. Moreover, they cannot be allowed to oppress significantly the 16m Remainers, let alone the 13 million non-voters.

So any deal agreed by Parliament should be sent for detailed consideration – perhaps by a Parliamentary Commission of both Houses (analogous to that in 2013 on Banking Standards). The Commission would take evidence on all the ramifications of each proposal so that all elements of Britain’s future place in the world are properly considered: foreign policy, security, economic etc.

Studies should be commissioned from all major global commentators so, in the economic field for example that could include the IMF, OECD, European Commission as well as HM Treasury and private sector players. (As a particular example, the City may not be popular but the impact on its contribution of 11% of tax revenues must be carefully considered as well as its £68 billion of foreign earnings. Even after this contribution, the UK’s current account deficit is £80 billion (4% of GDP – the worst amongst major countries.))

The Parliamentary Commission would have to assess the likelihood of EU27 accepting the proposals as the UK’s hope for a series of `unicorns’ must be tested against the reality already set down in the Political Declaration on the Future Relationship. Once we have left the EU, there can be no simple reversion to the status quo if we do not like the future relationship – vassal or not. The Parliamentary report must compare and contrast the likely eventual relationship with the current situation of full EU membership. The comparisons would be across all matters of significance to the UK’s future well-being.

Each elector would be sent an easy-read summary of the Parliamentary Commission’s report comparing and contrasting the two options so that no-one could say they were not informed on what they were voting about. There should have to be a minimum turnout – 75%? Parliament would only feel itself bound by an absolute majority of the electorate (23 million votes).

Whatever the result, a decision would then be made by Parliament within a few days to Leave OR to revoke the Article 50 notice of intention to leave.

In February, Dr Fox – the relevant government minster – released a statement saying it would not be able to replicate the EU”s free trade deal with Japan after Brexit as Japan has not agreed to continue existing trade terms in the event of no deal.

The economic power of the EU is fully recognised by its peoples as one of its major strengths. The UK is automatically part of about 40 trade agreements which the EU has with more than 70 countries.

However, the BBC Fact Checker reports that only 9 of these 40 are likely to be ready for rolling over. The volumes of these nine are pitifully low in comparison with the rest.

For a country dependent on foreign trade in both goods and services, being part of the world’s largest importer and exporter gives huge clout in negotiating trade deals. Third countries cannot give us a better deal in areas covered by their EU trade deals – current or in negotiation – without having to give the EU an equivalent deal – the Most Favoured Nation concept. Perhaps the trade experts are going to be proven right, so what is the point of leaving the EU?

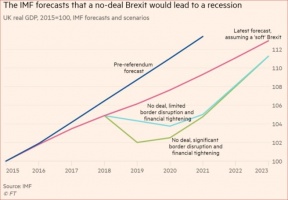

Ahead of the World Bank/IMF spring meetings, the IMF produced an economic forecast for the UK that included yet another lowering of expectations. However, a no-deal Brexit could be a severe blow to the economy. The Financial Times summarised the scenarios in this chart (right). The shortfall from the pre-referendum forecasts is painfully clear.

| Ahead of the World Bank/IMF spring meetings, the IMF produced an economic forecast for the UK that included yet another lowering of expectations. However, a no-deal Brexit could be a severe blow to the economy. The Financial Times summarised the scenarios in this chart (right). The shortfall from the pre-referendum forecasts is painfully clear. |  |

The Centre for European Reform (CER) publishes a regular update on the cost of Brexit relative to having continued on the 2016 growth path. Their March 2019 study says “The UK economy is 2.5 per cent smaller than it would be if Britain had voted to remain in the European Union. The knock-on hit to the public finances is £19 billion per annum – or £360 million a week.”What will be the impact on public opinion if the economic data in the months before a People’s Vote suggest that “the experts” are turning out to be right? In 1975, the negotiation of a “favourable” deal produced an 18% swing in the opinion polls about staying in. What will increasingly obvious proof of an “unfavourable “deal” do?

However, the 2019 referendum must not be a campaign of pitting one expert against another to undermine the Leavers’ case and expose the worsening of the nation’s standing that is widely expected. Instead, the positive case for being a full part of the European Union must be made.

The United Kingdom cannot escape from its geographical proximity to the mainland of Europe and its 66m population shares many aspirations with the other 440 million citizens of the EU27. But much of what needs 21st century renewal in Britain is entirely domestic so Europe has no role to play. It is the success of our economy that will deliver jobs and tax revenues – the life-blood of our communities and public services, as well as funding our defence and security.

However, in the modern world, there are many issues that transcend borders and then our vital national interests may coincide with our nearest neighbours – in Europe. So the question that should be at the heart of the 2019 referendum is whether `joining’ the European Union of the 2020’s could buttress, and amplify, future policies by the British political system – operating within the UK – that are likely to fulfil these aspirations of the British people.

The EU is also evolving rapidly. If sharing the EU’s policies in the near future make it more likely that Britain can deliver its own commitments to its own people, then we should remain a full member and encourage the policies that we believe will directly help us in Britain.

Eurobarometer 90 fieldwork was done last autumn and published in December. It found some strong trends of rising support for the EU’s policies “EU citizens support all but one of the EU priorities and common policies tested. Support is strongest for “the free movement of EU citizens who can live, work, study and do business anywhere in the EU”, with more than eight in ten in favour. After a slight increase, support for “a European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro” has reached its highest ever level in the euro area. Slightly more than seven in ten respondents feel they are citizens of the EU. For the second consecutive time this view is held by the majority of the population in all 28 EU Member States – only the second time this has happened since spring 2050.”

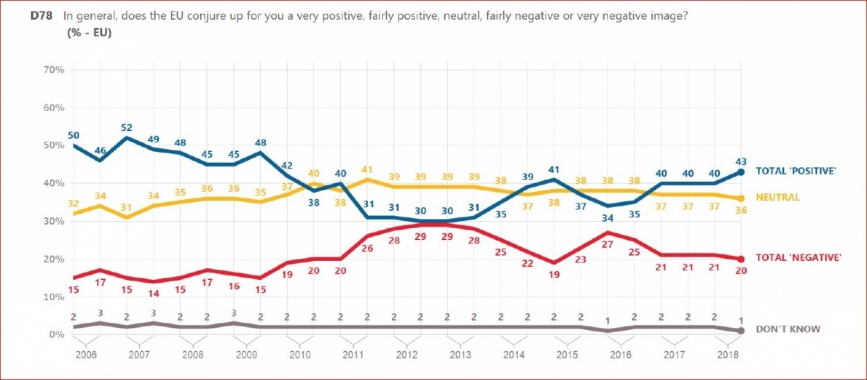

The paradoxical effect of Brexit has been to raise support strongly for the EU amongst citizens – up by more than 20% since the Brexit Referendum. Strikingly, “support” in the UK is at the EU average of 43% – with one of the strongest increases during 2018. Illustrating the polarisation in the UK, a negative view is held by 27% – one of the most negative views though far outweighed by the “positives”. The positive Europe campaign must focus on the factors contributing to this strong shift in favour of the EU concept – to make the case that we should want to `join’ it.

The Parliament elections in 2014 were fought in the shadow of the euro crisis when views for and against the EU were roughly balanced. The subsequent, steady recovery in the economy has powerfully boosted opinions about the EU. Will this be visible in the Parliament elections in May as it could mark a distinct shift in the perceived benefits of Europe, and thus the importance of the Parliament? If European opinion is on the move, Britain must surely be part of that movement.

Source: Standard Eurobarometer 90

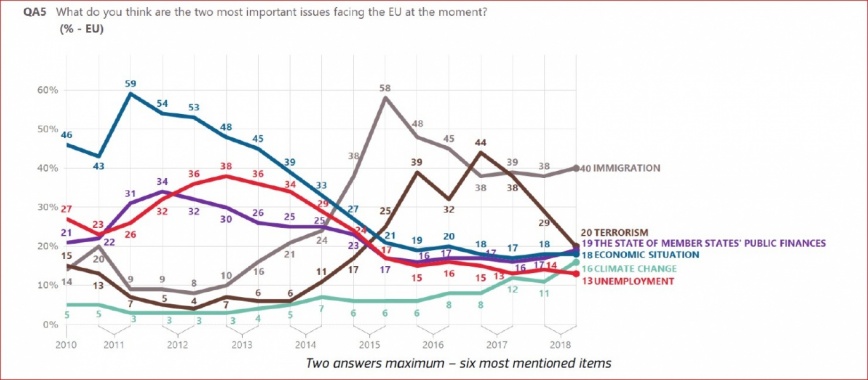

Source: Standard Eurobarometer 90

There are two striking features in the Eurobarometer data:

Should it come to negotiations on the Political Declaration on the Future Terms in the future, Britain’s Leavers must recognise that the European peoples will not allow anything that undermines the Single Market. So “cherry picking” will remain firmly off the agenda.

Given the geographic proximity and shared cultural history, it would not be surprising if the people of the UK and mainland Europe aspire to many similar goals, whilst also sharing concerns about factors involving the whole continent. Of course, there will be differences between states just as there are between regions within a state. The old industrial areas in the UK have different concerns to those of say London but many of these problems need to be tackled locally rather than nationally, or nationally rather than at Union level – the well-known principle of “subsidiarity” (see more detail European Parliament Fact Sheet).

1. What are UK electors concerned about? YouGov provides a tracker for the last few years. The data for April 2019 illuminates the shifts that can happen in public opinion as it responds to events. To stress again, the EU only has a policy role in a few of these areas so Leaving will not solve most of the public’s concerns.

a. Primary issues: Brexit is by far the most salient – named by 72% and is nearly twice the next issue – crime (34%). The third biggest issue is health (32%). Immigration/asylum has more than halved and slipped from top place in the immediate aftermath of the referendum to fifth – from 56% to 22%. Surprisingly, the economy is only in 4th place at the moment (27%).

b. Secondary issues named by 10-20% of respondents: Education, housing, environment, welfare benefits, and defence/security.

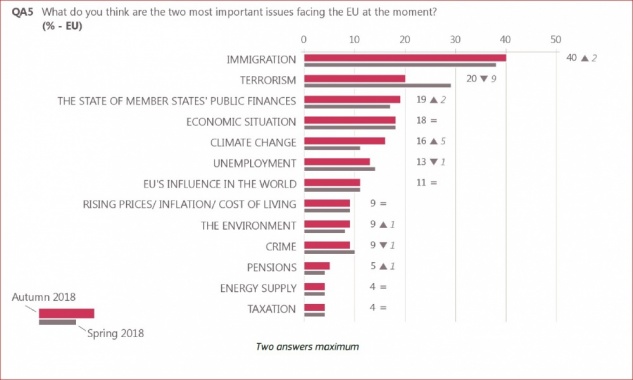

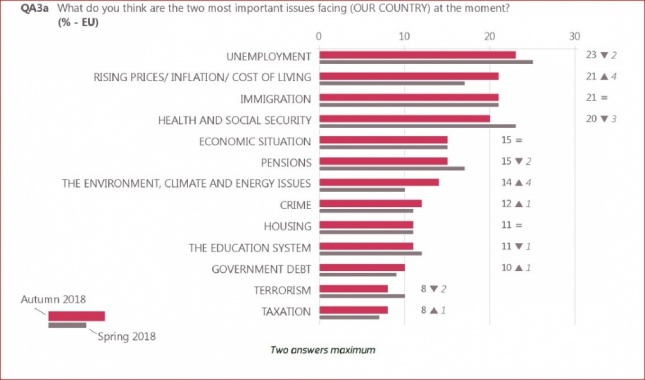

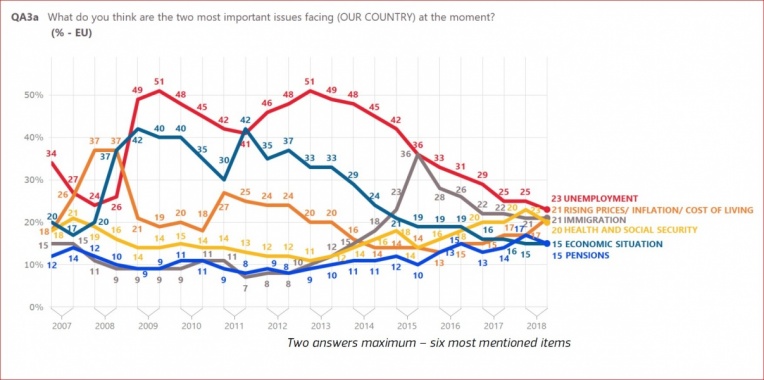

2. What are EU electors concerned about? The data comes from Eurobarometer 90 – published in autumn 2018. As this is a long-running set of standard questions, Brexit is not included. The key charts from Eurobarometer cover: the most important issues currently, a breakdown by country, and over time. These charts are in Appendix I and Appendix II.

(1) Immigration: Concern began to rise as the consequences of the Syrian war unfolded from 2011 onwards when only 9% of respondents put it in their top two concerns. By 2015, it was overwhelmingly the most important issue to 58% but has now dropped sharply to 40%. But it is still twice any other concern.

(2) Terrorism has followed a similar trajectory up and now down to 20%.

(3) Public finance and the economic situation have also sunk back from the levels of concern at the height of the crisis. The economic situation has fallen from its 59% peak to only 18% now.

(4) Unemployment has followed a similar path and is now only the sixth most concerning issue.

Comparisons between the UK and the EU27 states are very interesting – having excluded the British pre-occupation with Brexit. Immigration tops the list for both but the UK’s concern (31%) was well below the EU average (40%). The YouGov Tracker reports that, subsequently to Eurobarometer’s fieldwork, UK concern has dropped sharply again. UK concern about terrorism matches the EU average, as does concern about Member States’ public finances. The general economic situation is the fourth most important topic in both the UK and the EU.

Perhaps the biggest difference is in views about crime. It is the tenth most important topic in the EU but second in the UK. Its salience in the UK has shot up recently amidst the wave of knifings but crime is not a policy area where the EU acts at all. However, the European arrest warrant allows speedy extradition, and access to criminal/terrorist data is also acknowledged as being a major benefit of EU membership.

The broad conclusion is that UK and EU27 citizens share the same concerns about policy at the Union level. When the question is put about purely domestic policy problems, the UK shows some differences – most notably about unemployment where our rate is at record lows so is not a source of worry – though the implication about UK productivity certainly should be. Health and social security are dramatically more of a worry to UK citizens than in the rest of the EU – but they have been for many years. Again, these are not policy areas where the EU has any influence – except positive ones in say more efficient testing of medicines.

This paper is a substantially shortened version. The full paper is here http://grahambishop.com/StaticPage.aspx?SAID=583

More analysis “Never mind the Backstop: This is a bad deal, full stop.” People’s Vote (link)