Disclaimer2

Key Takeaways

How can Europe help its 25 million small and medium-sized enterprises better access finance and grow? These companies account for 99% of all EU businesses, half of its GDP, and two jobs out of three. However, SMEs can find it difficult to access finance given their smaller size, opacity, and somewhat weaker profitability than large firms. They therefore live on bank loans, credit lines, and leasing – their main three sources of financing (see: “Survey on the access of finance to enterprises,” European Central Bank, Nov. 24, 2021). What’s more, they have generally refrained from accessing capital market funding by issuing bonds or other securities.

To address these issues, the EU, through its Capital Markets Union project, aims to broaden access to a wider set of market-based sources of financing – including alternative sources – for all European companies at each stage of their development. This is reflected in Action 1 of the European Commission’s “Capital markets union 2020 action plan: A capital markets union for people and businesses,” adopted on Sept. 24, 2020. In particular, Action 5 seeks to direct SMEs to alternative providers of funding. A related discussion has emerged about whether direct SME funding through banks could be disrupted in Europe by the latest round of Basel rules regarding the capitalization of banks. This discussion has included questions about why only a small percentage of SMEs opt to obtain a credit rating to facilitate potential access local, regional, and international bond markets.

Here, we show how the funding structure European SMEs3 has evolved, with the aim of identifying how to enhance their access to traditional and alternative sources of funding. To perform our analysis, we used S&P Global Market Intelligence’s Private Company Financials database, comprising more than 800,000 records for EU companies (see the Annex). We classified them into four categories (micro, small, medium, large) according to their annual revenues. Then we determined how the share of their debt financing and equity financing has evolved. S&P Global Market Intelligence is an independent division of S&P Global, as is S&P Global Ratings.

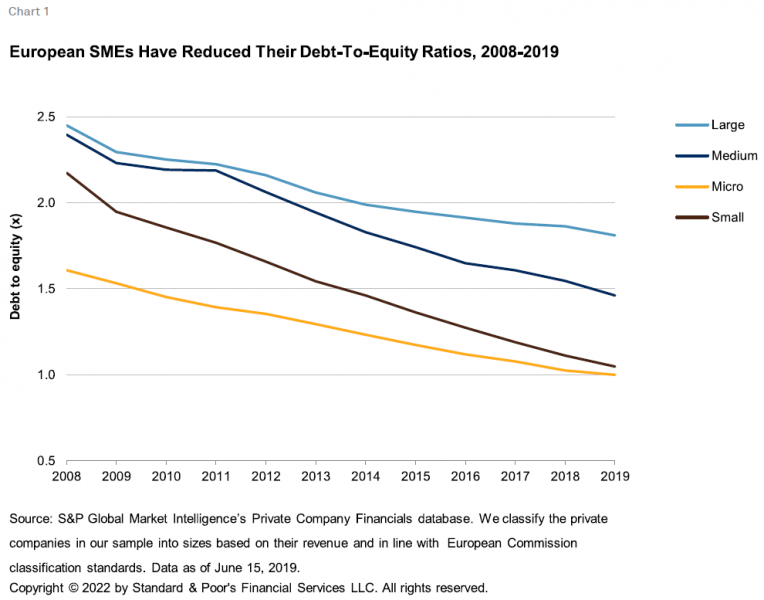

We found that European SMEs have reduced their debt compared to equity somewhat over the past decade. This improvement was more pronounced for SMEs than micro firms (see chart 1). These observations are in line with those of nonfinancial firms for 14 European countries available in the Banque de France’s Bank for the Accounts of Companies Harmonized (BACH) database.

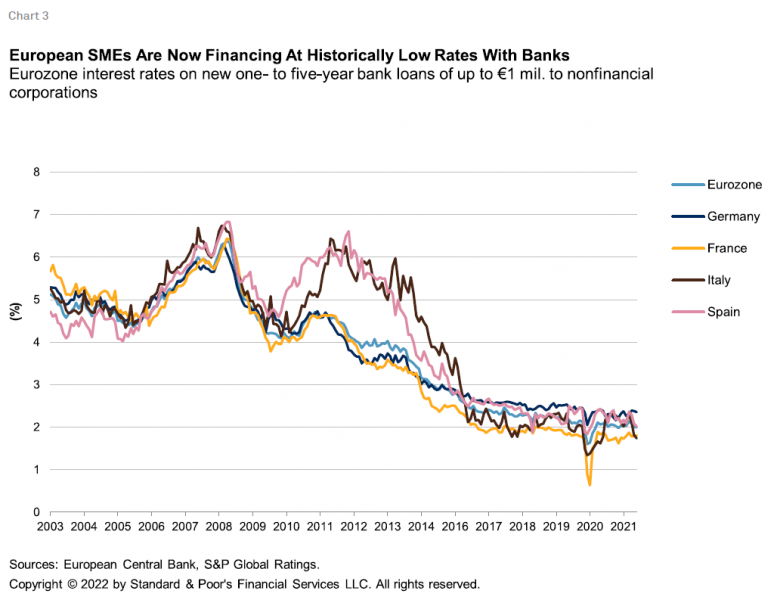

We don’t believe the shift from debt to equity means a strong improvement in the equity base of SMEs. Instead, it represents a consolidation, partly reflecting a rationing of bank loans and corporate deleveraging between 2009 and 2014 – especially in Spain and Italy. However, financing conditions have strongly improved for European SMEs in the past seven years. The large financing gap between funding needs and funding availability during the European debt crisis in 2011 and 2012, which was pronounced for micro enterprises, has been closed. Plus, the bold policy support granted to corporates during the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have helped avoid deep scars to their financing base (see chart 2). Today, European SMEs are financing at historically low rates – even negative in real terms – with banks. What’s more, the disparity in the cost of credit between the major economies of the eurozone has largely disappeared. In other words, the credit market for European SMEs is much less fragmented now than 10 years ago at time of the eurozone credit crunch (see chart 3), what is alone is a very positive outcome. So, the continuing shift from debt to equity after 2014 in an environment where the financing gap has been closed is an encouraging sign.

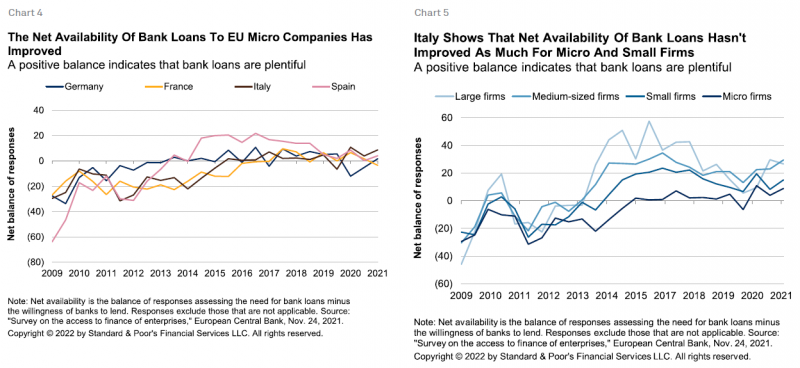

Since 2014, the availability of bank loans to SMEs has increased in all big eurozone economies and especially in those countries that suffered the most from the credit crunch at the beginning of the 2010s (see chart 4). However, the improvement has been less pronounced for micro and small companies than for medium-sized and large companies, a development that is very clear in Italy (see chart 5). That’s because Italian SMEs have a more capital-intensive profile, which is riskier for lending banks.

Several measures have been introduced in the last decade through regulators and central bankers to facilitate bank financing for SMEs. At the onset of the pandemic, this supportive policy stance continued. It was complemented by fiscal support measures, such as direct and indirect mitigation measures like government guarantees, which helped avoid another European credit crunch.

The SME Supporting Factor was introduced in the Capital Requirement Regulation (CRR) in January 2014 for all EU countries except Spain, which introduced it in 2013, notably diverging from the Basel accord. The purpose of the Supporting Factor was to reduce the potential adverse impact of the introduction of the countercyclical capital buffer between 2016 and 2019 on SME lending. In April 2020, the European Commission introduced its “quick fix” amendments to EU banking rules amid the pandemic and updated the Supporting Factor. This lowered capital requirements by up to 25 percentage points for loans granted to SMEs with an annual turnover not exceeding €50 million. These SME-specific measures lowered capital costs for banks and consequently reduced the borrowing costs that banks charge to SMEs as part of the price of loans.

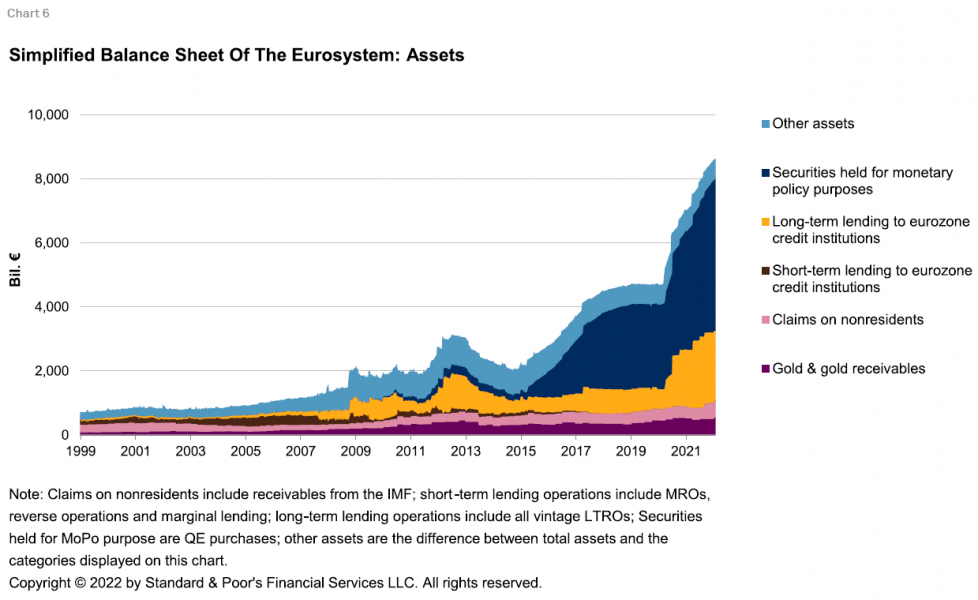

In parallel, the ECB started its quantitative easing (QE) program in 2014 with purchases of asset-backed securities and covered bonds and launched the first round of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). Both instruments have grown steadily in size as well as in scope since 2014, to the point where TLTROs make up a quarter of the ECB’s balance sheet and QE bond holdings half (see chart 6). The reduction of general interest rates because of these programs encouraged banks to expand net lending to the private sector, including SMEs, to meet the TLTRO conditions and receive the interest compensation in return.

The transition of the globally agreed final Basel standards into EU law is unlikely to constrict the bank lending channel for SMEs, in our view. Our base case is that European policymakers will maintain their pro-SME policy stance by including transitional arrangements to limit some of Basel’s negative impact on corporate and SME lending. We think that this policy stance will continue for the foreseeable future, at least as long as market-based financing still remains underdeveloped in Europe for SMEs.

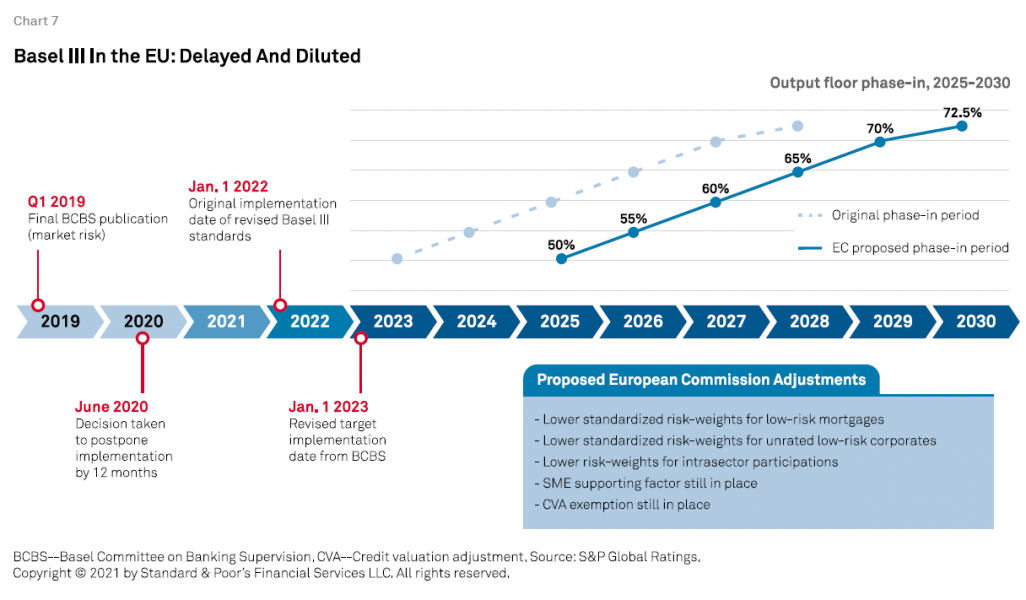

On Oct. 27, 2021, the European Commission published its draft directive and regulatory proposals to implement the Basel III regulatory framework into EU law. This directive, also covering capital requirements for SME exposures, would finalize implementation of the global revisions to Basel III (published in 2017) that aim to reduce disparities in the way global banks calculate credit, operational, and market risk – notably through their use of internal models. Already the result of intense lobbying, the proposal faces further political debate and potential tweaks before it is finalized and transposed into national laws. Originally targeted for implementation in January 2022, then delayed to 2023 after the pandemic hit, the revised rules will likely take effect in the EU from January 2025, with a five-year phase-in period, meaning that the framework will be fully in place by 2030 at the earliest.

When looking deeper into the likely to be delayed and gradually revised capital requirements rules under the proposed EU directive, we don’t expect a negative impact on SME lending. We rather find that it might have a mildly positive effect considering:

In what is a net positive for banks’ required size of regulatory capital, and therefore funding costs for SME lending, the new directive allows banks to use the standardized or the internal ratings-based approach for corporate and SME loans.

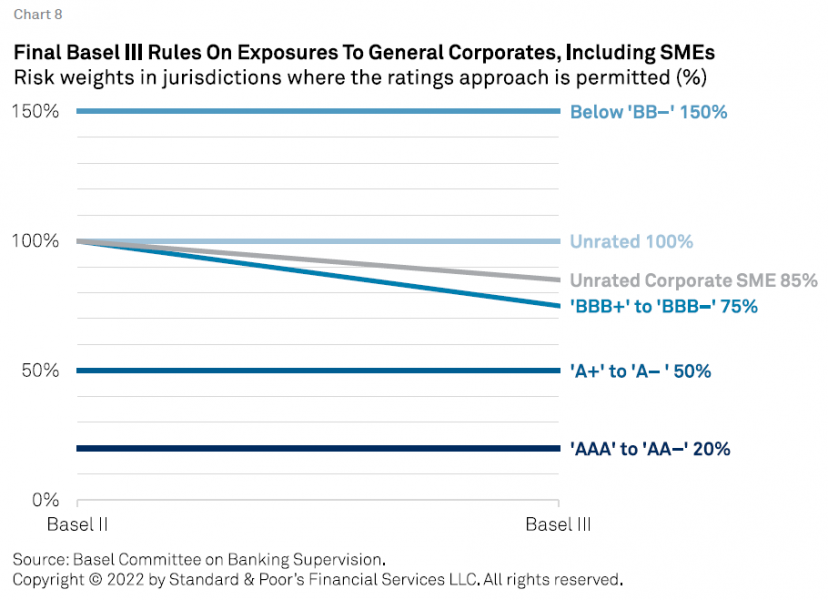

Standardized approach. Many banks that fund SMEs use the standardized approach for loan exposures to calculate credit risk-weighted assets – one component of the denominator of regulatory capital ratios. For example, the Bundesbank estimates that German banks use the standardized approach for up to 70% of loans granted to SMEs. Chart 8 shows the risk weights of the existing standardized approach and under the new Basel III rules. With the updated rules, standardized risk weights were lowered to 75% from 100% for SMEs rated ‘BBB+’ to ‘BBB-‘ for jurisdictions allowing the use of external credit ratings, while for unrated corporate SMEs (those with turnover of less than €50 million) the risk weight is reduced to 85% from 100% previously. For Europe, the SME Supporting Factor under the European Commission’s “quick fix” effectively implements the already lower risk weights of 85% for SME exposures (with turnover higher than €2.5 million) and even lower for below €2.5 million (76%).

Internal ratings-based approach. Some banks use internal models for their SME portfolio to calculate capital requirements. These models allow banks to estimate relevant risk parameters, such as the probability of default for loans and loss given default if a borrower is unable to pay back the loan, to infer capital requirements to cover potential credit losses in the future. The revised Basel III rules introduce some “input floors,” which will set minimum values for the parameters banks use to calculate their capital requirements under the IRB approach, resulting in increased capital requirements. What’s more, and a significant change from the previous Basel standard, an “output floor” will be introduced and restrict some of the beneficial effects from internal models to make these models globally more comparable. As such, the new output floor limits how much banks can reduce their capital requirements for loans relative to the standardized approach.

To smooth the impact of the introduction of the output floor, the EC has proposed to phase it in over five years. Starting from 50% of calculated credit risk-weighted assets (RWA) under the standardized approach in 2025, the output floor will increase gradually toward 72.5% in 2030 (see chart above). Considering the relatively large RWA impact from the output floor – particularly for unrated corporates and SMEs – the EC’s proposed transitional rule would avoid a negative impact on credit supply and give banks more time to adapt. In addition, banks would be allowed to apply a preferential risk weight of 65% of their exposures to corporates and SMEs when calculating the RWAs for the output floor, at least until the end of 2032.

That said, the proposed rule would apply only to exposures to unrated corporates and SMEs with a probability of default of less than or equal to 0.5%, which corresponds to an “investment-grade” rating according to the view of the European Commission.

The IRB approach is no longer applicable for the calculation of RWAs for equity investments in corporates and SMEs. Banks have to use the standardized approach, which would lead to higher RWAs under new Basel rules, for example, 250% for standard corporate equity exposures and 400% for speculative equity investments. To somewhat offset this tightening, European lawmakers have also proposed to reduce the impact by carving out equity investments deemed as “long-term strategic” from the 400% classification, to bring it back to 250%, and by introducing a transition phase of five years for both the 250% and the 400% exposures.

In their implementation of Basel rules, European policymakers have continuously sought to avoid negative consequences from tightening banking regulations on SME lending. We expect this stance to continue in the future, at least until banks are the ones to provide most SME funding.

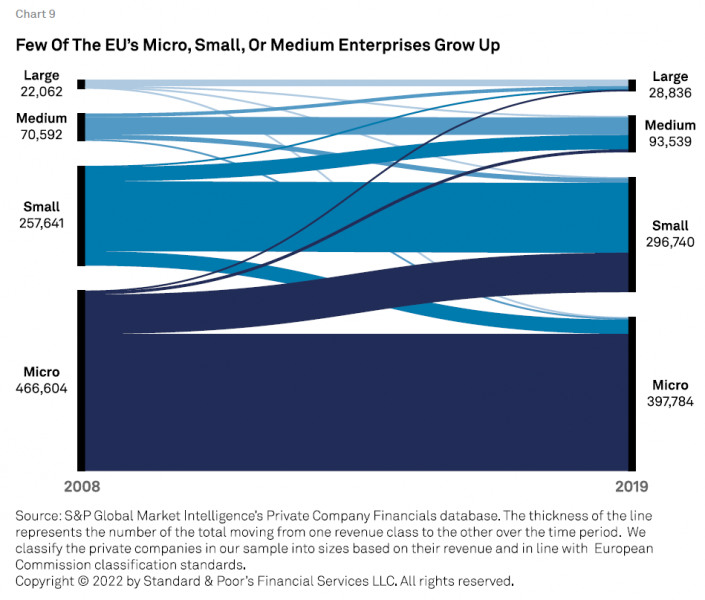

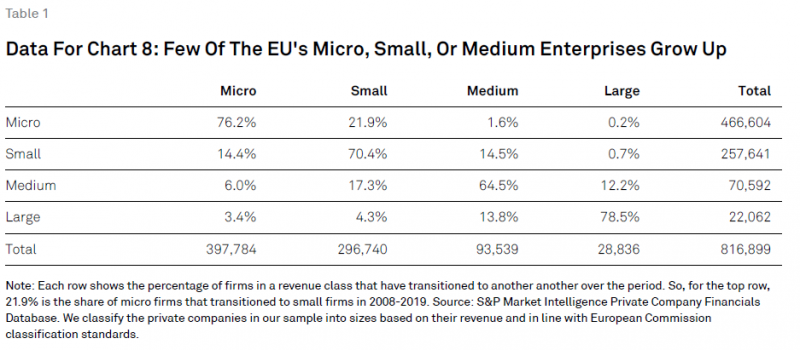

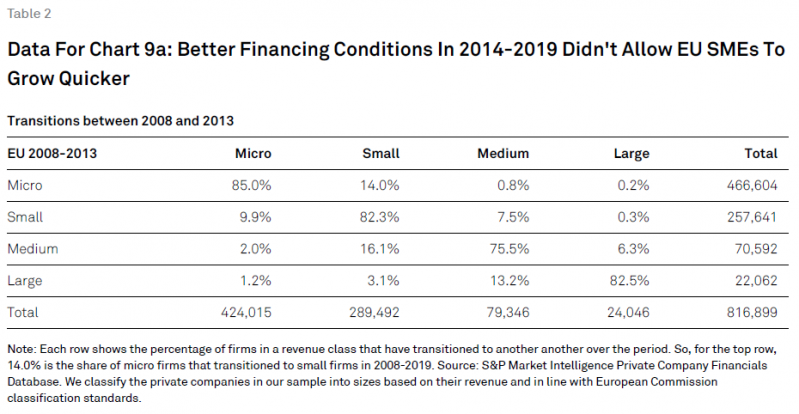

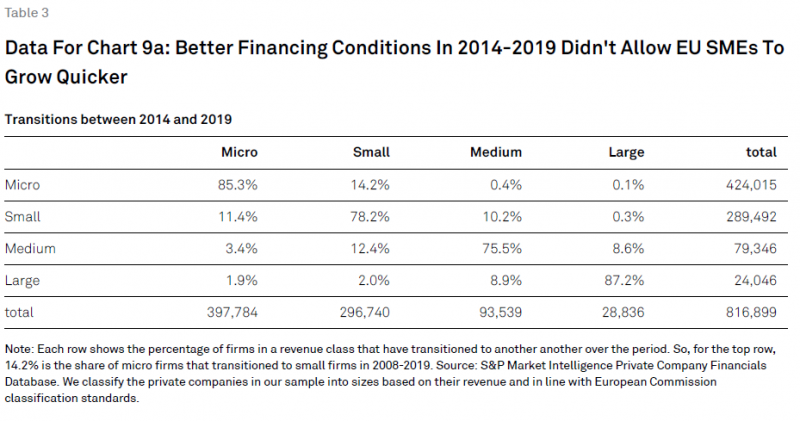

We find that SMEs based in the EU are slow to grow. Investigating the share of companies within our database that have moved from one category of revenues to another from 2008 through 2019, we find that less than a quarter (23%) of micro enterprises have moved to the next category of revenues. Even fewer small (15%) and medium-sized (12%) enterprises have done so (see chart 9). There is no major difference in this transition whether the companies are based in the European Monetary Union (EMU), the Nordic countries, or the U.K. We find that U.S. SMEs present in our sample are much more dynamic in this respect.

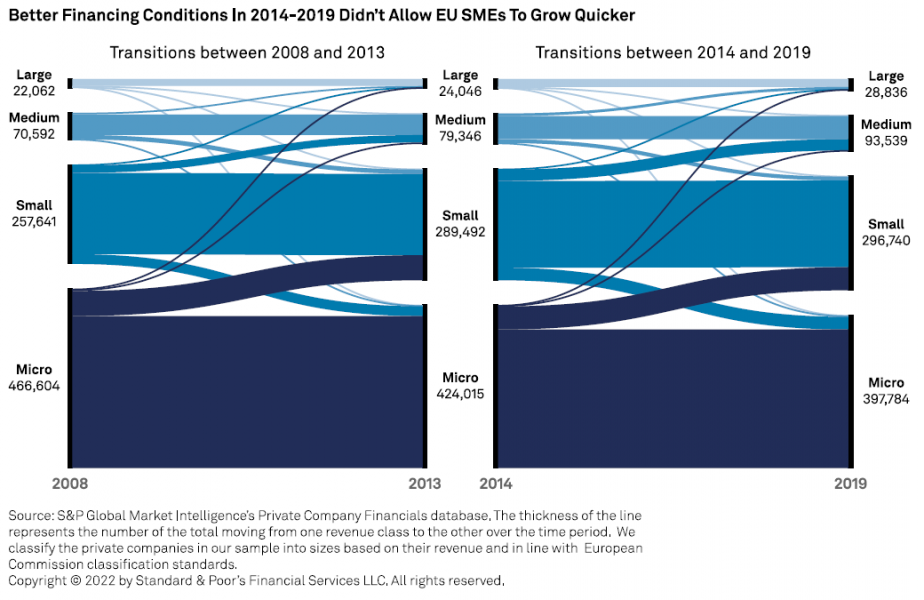

What’s more, improved financing conditions have not allowed European SMEs to grow faster. European SMEs did not grow quicker in terms of revenue between 2014 and 2019 (a time of loose financing conditions and incentives for banks to grant loans to SMEs) than they did between 2008 and 2013 (the global financial crisis and the European debt crisis), whatever their initial size (see chart 10). However, we note that slightly fewer large and medium-sized firms fell back into the lower revenue category in the second period.

![]()

It can be argued that easier financing conditions have not led to higher growth because European companies operated in the same slow growth environment. However, with SMEs accounting for half of European GDP, it can also be argued that more investment from their side would have changed the environment where they operate.

Our findings at first glance confirm the widespread view that not only the available amount and cost but also the kind of financing matters for SMEs in Europe. Several studies highlight the uneven impact of SME financing practices on their economic performance. In the past, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development identified private equity financing as a source of growth for SMEs. The use of private equity, venture capital for the most part, is said to increase operational efficiency and earnings, boost investment, and employment (see “EBRD Transition Report 2015-16: Rebalancing Finance,” especially Chapter 4, Nov. 10, 2015). More recently, the think tank New Financial pointed out that capital markets improve the allocative efficiency of capital by effectively crowdsourcing decisions about value and potential to a wide range of investors and channeling investment to its best possible use (see “A New Vision for EU Capital Markets,” February 2022). These views suggest that the kind of financing, rather than the shape of it – which we examined in the first part of this article – is key to boosting economic performance. Indeed, SMEs today have more than a binary choice of financial themselves via bank loans or debt capital markets. The development of leasing, factoring, and crowdfunding has increased funding alternatives for SMEs. Similarly, the think tank Bruegel has documented an acceleration in venture capital for EU companies (see “Venture capital: a new breath of life for European entrepreneurship? Feb. 10, 2022). If sustained and sustainable, SMEs’ increased recourse to venture capital might increase the allocative efficiency of capital. This may mean that finance of the future, rather than forms of the past, could be more effective ways to jumpstart growth of Europe’s SMEs, and with it, the livelihoods of millions of people.

How we used S&P Global Market Intelligence’s Private Company Financials database

This research is mainly based on S&P Global Market Intelligence’s propriety database Private Company Financials, which provides more than 200 standardized financial statement items for some 10 million private companies globally. Driven by our research questions, we tapped the database to constitute our working data set, mapping financial data with company-specific, currency, geographic, and other information.

To keep the same population of companies over the period of investigation, we had to restrict our sample to 1.1 million private companies, of which 76% are based in the EU (excluding the U.K.), 14% in the U.K., 10% in the Nordic countries outside of the EU, and less than 1% in the U.S. (rounded numbers). The geographical distribution reflects the nature of the Private Company Financials database, specifically, the expansion in coverage of European companies through 2020 and 2021, and data provided to S&P Global Market Intelligence through its partnerships with third-party providers. We did not apply any methodology that would skew the geographical distribution of the original sample. All revenue data were converted to euros, using foreign exchange rates published by the ECB.

Giorgio Baldassarri, group manager for quantitative modeling at S&P Global Market Intelligence, and David Doyle, S&P Global’s Head Of Government Affairs And Public Policy, EMEA, also contributed to this report.

This policy note does not constitute a rating action. S&P Global’s opinions, quotes, and credit-related and other analyses are statements of opinion as of the date they are expressed and not statements of fact or recommendations to purchase, hold, or sell any securities or to make any investment decisions, and do not address the suitability of any security. Copyright © 2022 by Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC. All rights reserved.

How we define small and medium-sized enterprises: For this report, we borrow the European Commission’s definition of a SME (see: “SME definition” ec.europa.eu). Micro companies have revenue up to €2 million a year. Small companies have annual revenue up to €10 million, medium-sized companies up to €50 million, and large companies greater than €50 million.