In recent decades, we have seen a persistent decline in interest rates across the globe. This has been driven by a decline in the underlying natural real rate of interest and since the global financial crisis also by subdued rates of inflation in many countries. In Denmark, the key policy rate has been negative for most of the past decade. For the financial sector, negative interest rates are increasingly becoming business as usual. For households and non-financial firms, preliminary evidence suggests that banks’ introduction of negative deposit rates had behavioural effects on top of the standard effects of a reduction in deposit rates.

In my remarks2 today, I will explore the topic of low interest rates from a Danish perspective. I hope that this will set the scene for today’s discussions in what will surely be a very fruitful conference.

The persistent decline in a wide set of interest rates is one of the most important topics in modern macroeconomics and finance. It is driven by a host of underlying factors operating at a global level, and it has implications for households, firms and financial institutions of all shapes and sizes.

The decline in interest rates is also affecting the scope for conducting economic policies. Most obviously, it challenges the effectiveness of conventional monetary policy as policy rates have moved closer to their effective lower bound. But it also has implications for the conduct of fiscal policy as well as for the optimal deployment of macroprudential tools. The link between low interest rates and fiscal policy in Denmark will be the topic for the panel discussion later this morning.

As Governor of Danmarks Nationalbank, the causes and consequences of very low interest rates is something that has been high on the agenda for at least a decade. In July 2012 we were the first central bank to introduce negative policy rates. And in early 2015 we reduced our key policy rate to -0.75 per cent. This means that together with the Swiss National Bank, we are the central bank that has operated with the lowest level of the key policy rate.

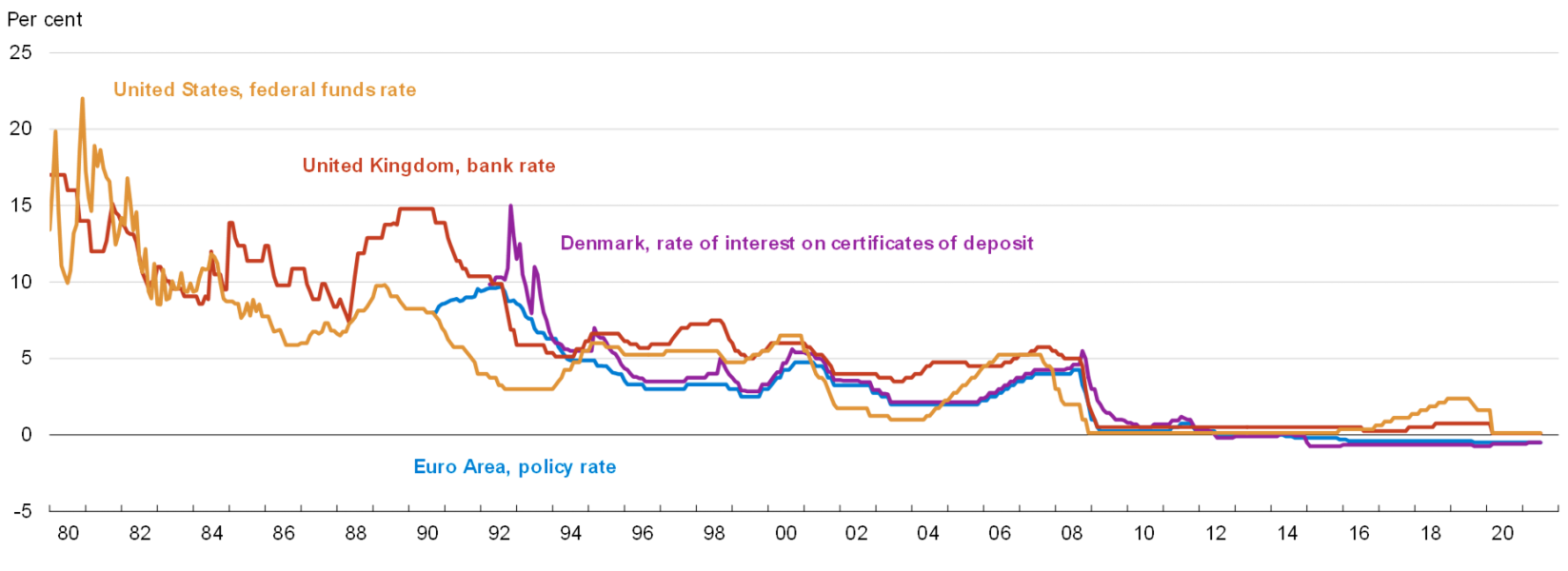

While we have been at the forefront when it comes to low and negative interest rates, we are clearly part of an international trend. Policy rates are currently negative in Denmark, Switzerland, Japan and the euro area. And in most other advanced economies, they are close to zero. This did not happen overnight. As you can see from chart 1, policy rates have been trending downwards since the 1980s.

Chart 1: Policy rates have declined across the advanced economies

Note: Up until 1999, the Euro Area policy rate is represented by Deutsche Bundesbank’s repo rate. From January 1999 till October 2008, the policy rate is represented by the ECB’s main refinancing operations rate. From November 2008, the policy rate is represented by the ECB’s deposit facility.

Source: Macrobond.

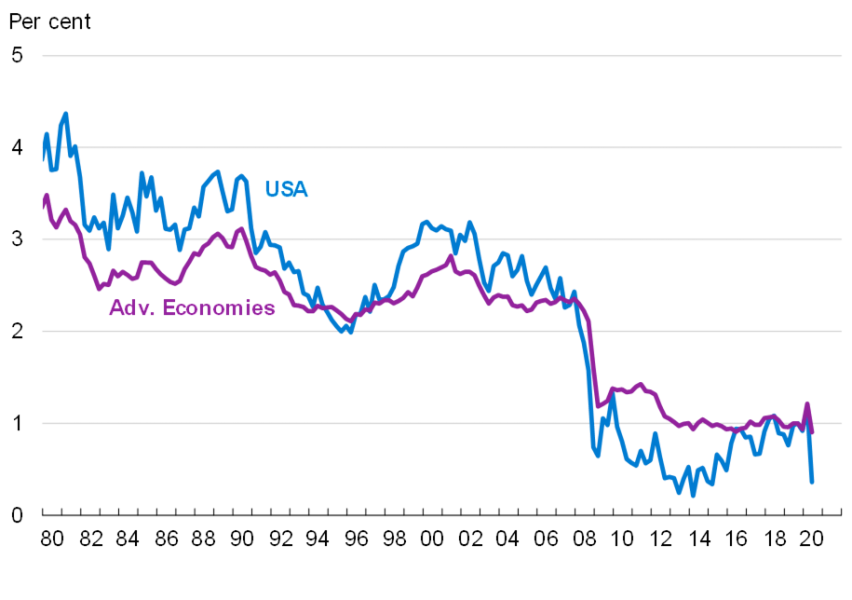

The secular decline in interest rates is no coincidence. It reflects key underlying economic and financial developments. First, the underlying equilibrium real interest rate, or r* for short, has declined. This is the real rate of interest that balances savings and investments so that inflation remains stable. Chart 2 shows estimates of r* for Denmark, the United States as well as a group of advanced economies.

Chart 2: Low policy rates reflect decline in equilibrium real rate of interest

|

|

Note: The natural real rate of interest is estimated with considerable uncertainty and the level differences between Denmark and the US/Advanced economies may reflect differences in estimation methods.

Source: Thomas Laubach and John C. Williams, 2003, Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest, Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol 85(4), Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach, and John C. Williams, 2017, Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants, Journal of International Economics, Vol 108(1), and Jesper Pedersen, 2015, The Danish natural real rate of interest and secular stagnation, Danmarks Nationalbank Working Paper No. 94.

The decline in r* reflects that from a global perspective, desired savings have risen relative to desired investments.3 But as we cannot interact with Mars, realised investment must equal realised savings at the global level. This means that in equilibrium, interest rates have declined.

Changing demographics have been identified as a key factor behind the decline in r*. In particular, an ageing population is found to have been driving up desired savings, thereby pushing down equilibrium interest rates.

Moreover, the decline in productivity growth that has been observed in many advanced economies since the 1990s may have reduced the incentive for firms to invest in new equipment. At the same time, slower productivity growth and hence slower growth in earnings may have contributed to higher household savings rates. If a household expects its incomes to increase substantially it has less incentive to save for the future. From that logic, weaker growth in incomes will tend to increase savings, putting downward pressure on r*.

The distribution of income and wealth across individuals is also a potential factor behind the decline in equilibrium interest rates.4 In a number of countries, the distribution of wealth in particular has become more uneven. As the wealthiest part of the population typically has a lower propensity to consume, this has contributed to an increase in global desired savings and hence a decline in r*.

We observed a pronounced decline in estimates of r* in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis. This is likely to reflect that the financial crisis led to a general reassessment of risks among firms and households in many countries, prompting them to deleverage. With a more cautious approach to savings and spending, r* must fall. This has been corroborated by stricter financial regulation that was implemented in response to the crisis.

The link between financial regulation and interest rates goes two ways. While a more prudent approach to spending and savings may have reduced equilibrium interest rates, an extended period of very low rates may in itself call for tighter regulation. In particular, such an environment may increase the risk of unsustainable increases in asset prices. This may be the case if investors take on more risk to increase returns or if they become overly optimistic about further increases in asset prices, thereby fuelling an asset price bubble. This leaves an important role for appropriately designed macroprudential measures.

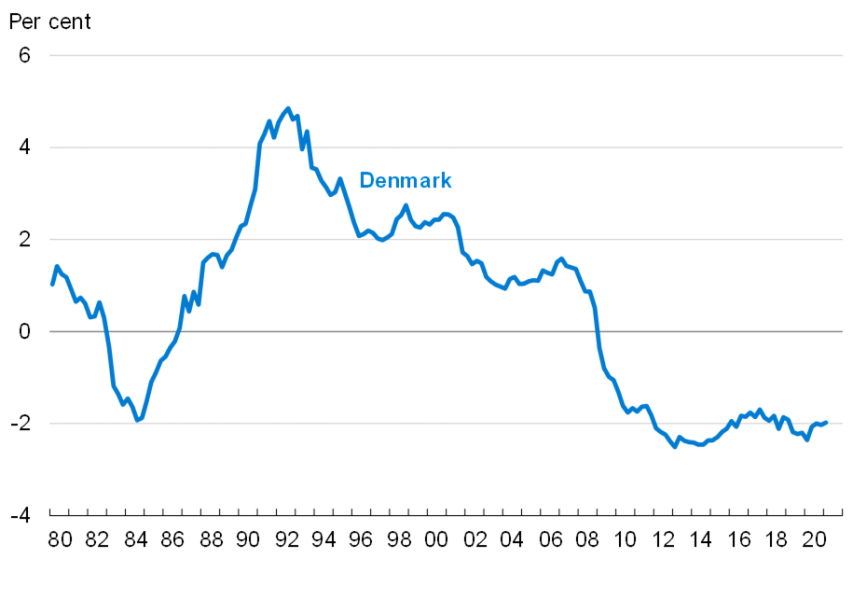

In addition to the decline in r*, very low policy rates in recent years also reflect that central banks have tried to stimulate aggregate demand in order to reach their inflation targets. In fact, inflation in many advanced economies has been subdued for an extended period of time as illustrated by chart 3.

Chart 3: Extended period of subdued inflation following global financial crisis

Note: Consumer prices, annual rate of change.

Source: Macrobond.

It is not the first time in history that real interest rates are negative across a number of advanced economies. But whereas earlier episodes of negative real rates have reflected temporary bouts of inflation, this time it has coincided with highly subdued price pressures in many countries.

While the key priority of monetary policy used to be to avoid inflation running too high, many central banks are currently struggling to avoid a situation where inflation drifts too far below target and inflation expectations risk becoming de-anchored. To that end, low policy rates have been accompanied by a number of other measures such as quantitative easing and forward guidance.

Danmarks Nationalbank sets policy rates with the sole objective of keeping the Danish krone pegged to the euro. This means that we do not consider developments in equilibrium interest rates or inflation when making decisions on monetary policy. But the policy regime implies that our policy rates closely follow those of the ECB. So, in that sense the decline in our policy rates reflects the same factors that have driven down interest rates in the euro area.

Significant deviations between Danish and euro area policy rates only occur in situations with considerable pressure in foreign exchange markets. In fact, the initial introduction of negative policy rates in 2012 reflected substantial capital inflows amid the European sovereign debt crisis. And the reduction of the policy rate to a record low of -0.75 per cent in early 2015 was necessitated by very strong capital inflows following the decision of the Swiss National Bank to discontinue the ceiling on the Swiss Franc and the subsequent announcement of a large scale asset purchase programme by the ECB. But despite very low Danish monetary policy rates, subdued consumer price inflation means that real interest rates in Denmark are not lower than in a number of other countries.

While the decline in interest rates reflects underlying economic developments, the emergence of very low and even negative interest rates in itself has important implications. In that respect the pension sector is of particular interest as it makes decisions based on expected returns over very long horizons. And in Denmark, assets in pension funds and other retirement vehicles constitute more than 200 per cent of annual GDP, which is very high in an international comparison.5

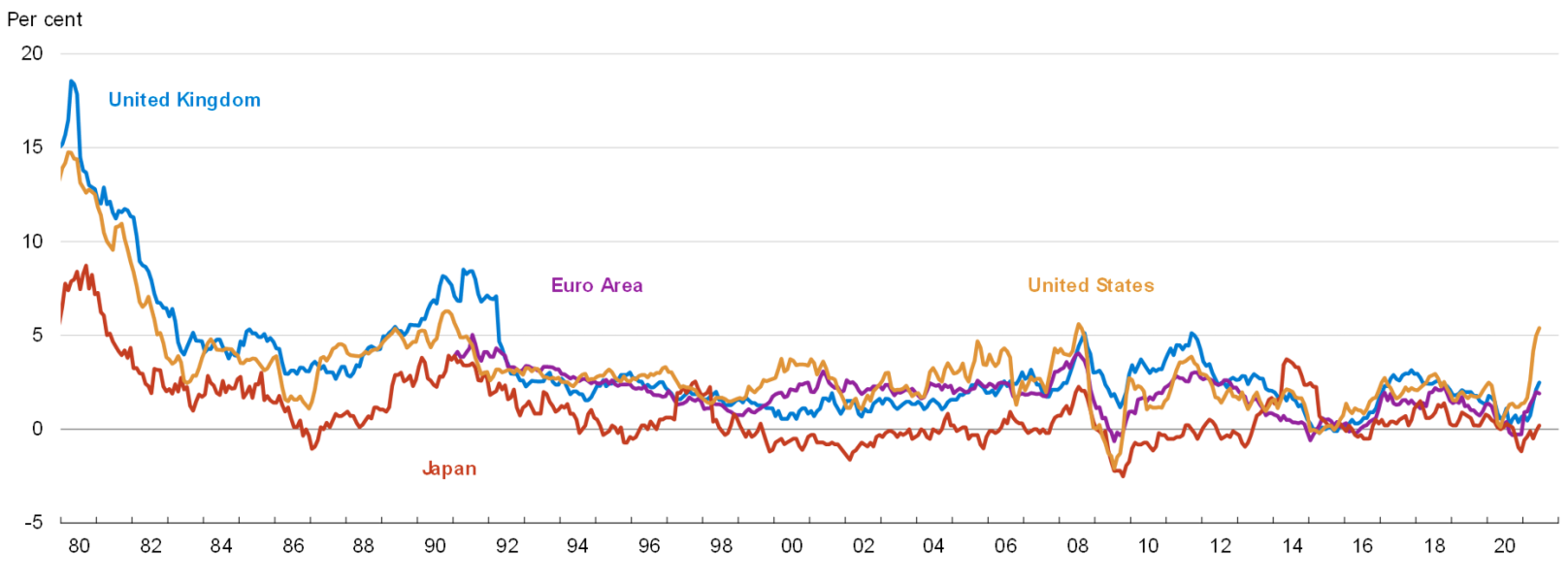

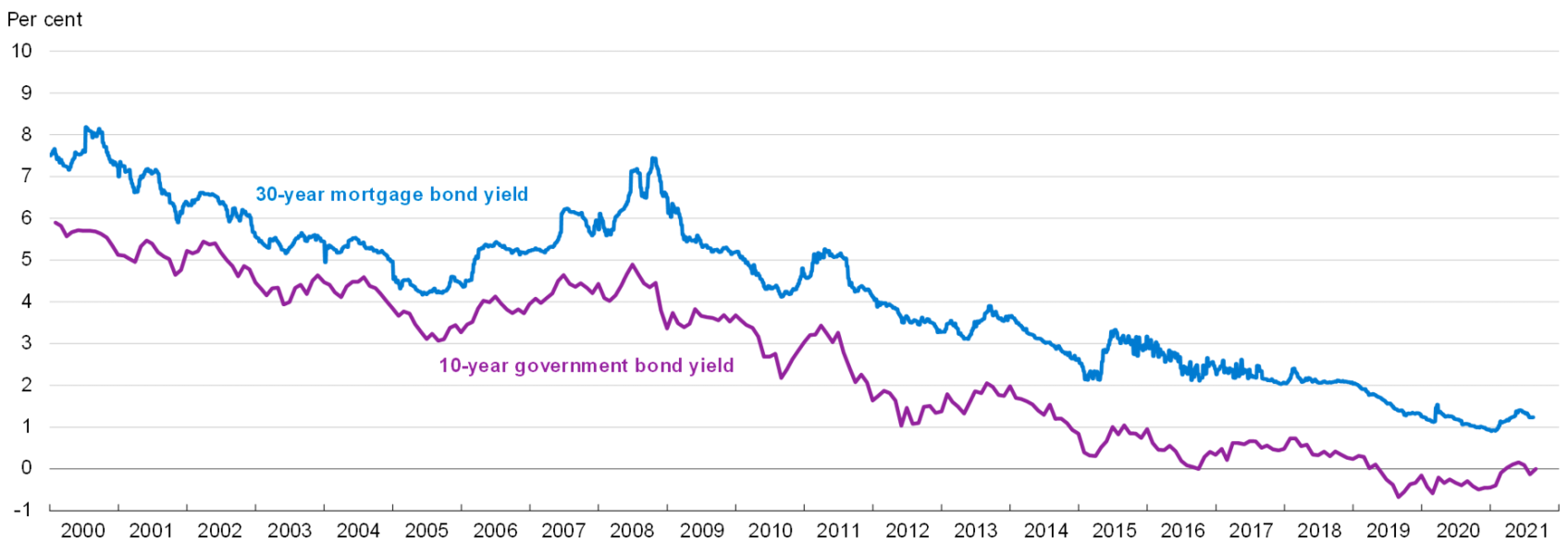

Chart 4 illustrates how long-term yields have declined over the last two decades, driving down the returns that pension funds can expect to earn on their investments. The decline in expected returns coincided with a substantial increase in longevity. Decreasing returns in conjunction with rising longevity may appear as a dangerous cocktail for a pension fund. But by shifting savers from schemes with a guaranteed minimum return to market-based schemes, Danish pension funds have reduced the impact of changes to returns and longevity on their financial position.

Chart 4: Danish long-term yields have declined

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream.

There is an ongoing debate about how pension savers respond to lower expected returns. The intertemporal substitution effect suggests that as return on savings declines, savers are encouraged to save less and spend more. But there is also an income effect – lower returns on pension savings make savers worse off in retirement.

In conventional macroeconomic models, the substitution effect dominates the income effect – when the interest rate declines, savings fall. This is also how I would expect interest rates to affect total private sector savings.

It may be worth taking a closer look at the interaction between the two effects when it comes to pension savings. Whereas total net financial wealth of Danish households is negative, pension savings are obviously positive financial wealth from the perspective of households. This is likely to increase the importance of the income effect for this particular component of savings. If households for example aim at achieving a specific replacement ratio at the time of retirement, low real interest rates imply that they have to save more. But as we are in unchartered territory with negative nominal rates, more research in this area is vital.

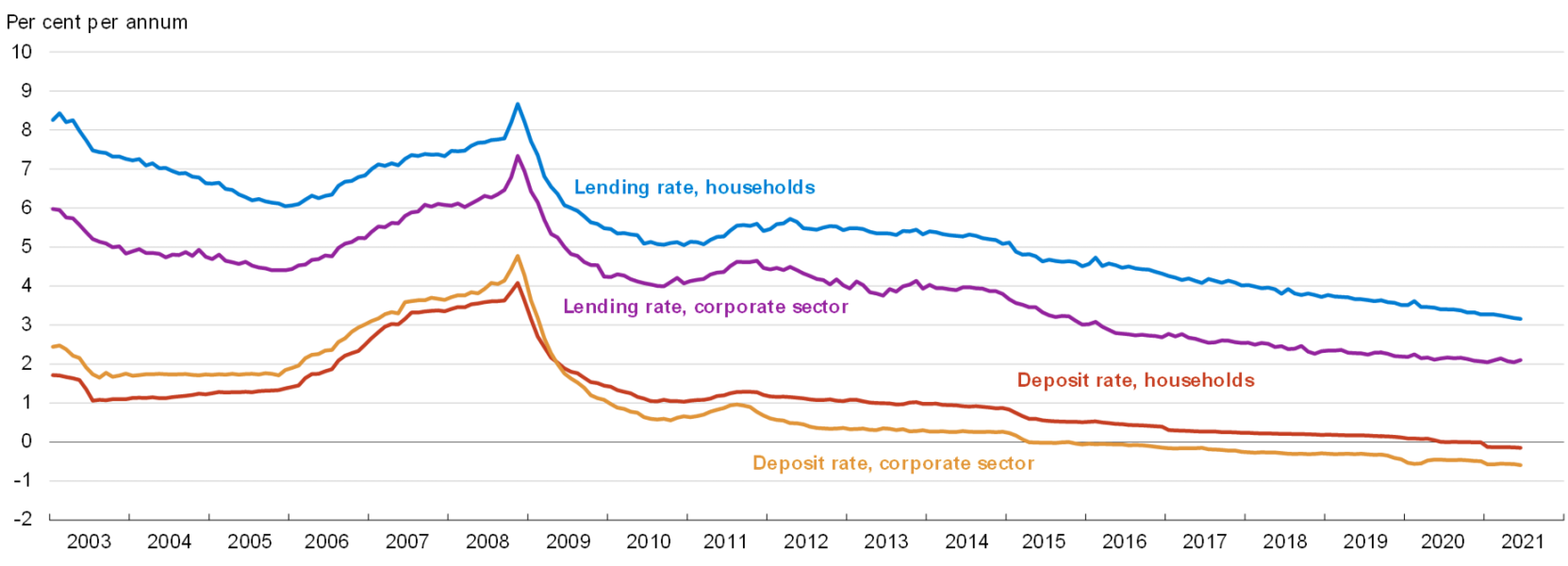

Many households and firms most directly feel the impact of low interest rates via their bank. Lending as well as deposit rates have declined alongside the reduction in policy rates as illustrated by the chart 5. For lending rates, pass-through from policy rates has been more sluggish than what we are used to. But we have not seen indications of a so-called reversal rate, where negative policy rates become a drag on lending.6

Chart 5: Deposit rates have become negative in Danish banks

Note: The chart shows Danish banks’ average lending and deposit rates for households and corporates.

Source: Danmarks Nationalbank.

Now look at deposit rates. While our key policy rate first became negative in July 2012, it was not until the beginning of 2015 that banks started charging negative deposit rates to firms. Initially for large firms and institutional investors, but increasingly to firms more generally.

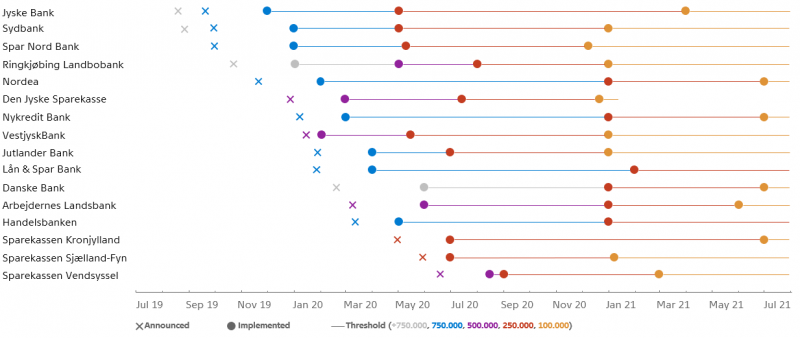

For several years, household deposit rates appeared to be subject to a zero lower bound. But in August of 2019, Jyske Bank announced as the first Danish bank that it would charge negative rates on large household deposits with effect from December of that year. Since 2019, most Danish banks have introduced negative rates on deposits exceeding a certain threshold as illustrated by chart 6. Currently the threshold is typically DKK 100,000, with deposits in excess hereof being remunerated at a rate of -0.6 per cent.7 The banks have been reducing the threshold in steps as they have been venturing into unchartered territory.

Chart 6: Most banks have introduced negative deposit rates for households

Source: Individual bank press releases.

In Danmarks Nationalbank, we have analysed how Danish firms and households have responded to negative deposit rates. We find that when a firm is exposed to negative deposit rates, it increases the likelihood that the firm will move its deposits to another bank.8 Moreover, it becomes more likely to repay debt. The effect of negative rates is not limited to financial decisions. Firms that are charged negative deposit rates also increase employment and investment in fixed capital compared to other firms.

These findings suggest that the response of firms to changes in deposit rates is non-linear at zero. This could reflect an ’awareness effect’ – when firms are exposed to negative deposit rates they may become more aware of their economic situation. For example, firms with large bank deposits are often approached by their bank when it introduces negative deposit rates. Negative rates could also increase the risk appetite of firms, explaining the observed pickup in employment and investment.

Somewhat similar to what we see for firms, there are indications that households reduce deposits with banks that announce negative deposit rates.9 In addition, they appear to increase their demand for investment fund shares and switch their deposits to pool schemes.

As negative deposit rates for households are still a recent development, we can only speculate on their wider implications. When new data becomes available, it will be pertinent to study to which extent negative deposit rates lead households to increase their spending – for example by purchasing a new car or move to a more expensive home. If this is the case, negative deposit rates may lead to more lending. But if households instead simply reduce their deposits by paying back debt, lending could decline.

The transmission of negative policy rates is likely to differ across countries for a number of reasons. For example, some countries have legislation that restricts banks from imposing negative deposit rates.10 Nevertheless, the key lesson that I draw from our experience is that for the financial sector, negative interest rates are increasingly becoming business as usual. Even the key non-linearity associated with negative rates – the lack of transmission to deposit rates – is fading.

For non-financial firms, preliminary evidence suggests that the introduction of negative deposit rates had real effects on top of the standard effects of a rate cut. This may also have been the case for households although more evidence is needed in this area. But as firms and households become more accustomed to paying interest on their deposits, these effects may be attenuated.

Of course, there is a limit to how low rates can go. But we have seen that negative policy rates are a viable policy tool in a world of low equilibrium interest rates. Demographic factors suggest equilibrium interest rates are likely to remain low for the foreseeable future. This suggests that the topic for this conference could not have been more relevant.

I would like to thank Morten Spange for his support in preparing these remarks, as well as colleagues at Danmarks Nationalbank for helpful comments.

Opening remarks held by Lars Rohde, Governor of Danmarks Nationalbank, at the conference “Long run outlook for interest rates”, on 1 September 2021.

See e.g. Claus Brand, Marcin Bielecki and Adrian Penalver (editors), 2018, The natural rate of interest: estimates, drivers and challenges to monetary policy, ECB Occasional Paper No. 217, and the references therein.

See e.g. Lawrence Summers, 2014, US economic prospects: Secular stagnation, hysteresis, and the zero lower bound, Business Economics, Vol 49(2), National Association for Business Economics.

See OECD, 2021, Pension Funds in Figures.

See Jakob Feveile Adolfsen and Morten Spange, 2020, Modest pass-through of monetary policy to retail rates but no reversal, Danmarks Nationalbank, Working Paper No. 154.

This threshold typically applies only if the customer uses the bank as its primary bank – otherwise negative rates apply to the full amount. Currently households pay negative interest on approximately one third of their total bank deposits.

See Kim Abildgren and Andreas Kuchler, 2020, Do firms behave differently when nominal interest rates are below zero?, Danmarks Nationalbank, Working Paper No. 164.

See Rasmus Kofoed Mandsberg, Alexander Meldgaard Otte and Morten Spange, 2021, The response of household customers to negative deposit rates, Danmarks Nationalbank, Analysis no. 9.

See European Banking Authority, 2020, Risk Assessment Questionnaire – Summary of the Results.