We study the extent of monetary-fiscal interactions in the case of conventional and unconventional monetary policy for the four largest countries of the euro area. We find that the more modest impact on inflation of unconventional monetary policy easing compared to the response to a conventional easing, is associated with a conditional insignificant increase in the primary surplus in the former case and with a deficit in the latter case, both at business cycle frequency and in the long-run. This result may explain the more muted impact of non-standard monetary policies in the euro area when compared with the US and the UK.

The topic of coordination between monetary and fiscal policy has become the focus of policy discussion in recent years (Draghi, 2014, Lagarde, 2020, Schnabel, 2021). One reason is that there is limited space for traditional monetary policy based on steering the short-term interest rate when the latter is at or close to the effective lower bound (ELB). Many recent papers have advocated mechanisms to implement a coherent a monetary-fiscal policy mix (see for example the policy report by Barsch et al 2021).

In the euro area, the treaties are based on the assumption that monetary and fiscal policy can be and should be separated. The rigid separation between monetary and fiscal policy is achieved via an independent central bank with a narrow mandate and nineteen fiscal authorities committed to (fiscal) rules. It is the legal consequence of the belief that in an asymmetric federation, with a single monetary policy authority and nineteen fiscal authorities, macroeconomic stability is best achieved by a combination of a credible and independent central bank targeting price stability, and fiscal rules setting public deficit and public debt limits.

Operationally, the ECB acts on its mandate, and fiscal authorities react (monetary dominance). This design provides a sort of passive coordination whereby monetary policy always controls the price dynamics, and fiscal authorities take that as given. Since both the central bank and the fiscal authority are part of the government sector, this design corresponds to a particular institutional choice motivated by the idea that an independent central bank with a mandate of price stability should take the lead (“active” in economic jargon) while fiscal policy is constrained (“passive”) and cannot monetise public debt and hence has to generate real surpluses to pay for it. This design does not deny the inevitable interaction between monetary and fiscal policy, but it favours a particular coordination scheme between the monetary and fiscal authorities. Fiscal policy undertakes stabilization policy at the level of each member state, taking the common monetary policy as given, and subject to a set of fiscal rules – the “Stability and Growth Pact” (SGP) – that was created to operationalize the prohibition of excessive deficits.

The pros and cons of such design have been the object on an intense debate over the years and the rules of the SGP are currently being assessed by the EU. But independently from the normative question of whether there is a need for reform, the empirical question still remains unanswered. How have national fiscal policies responded to monetary policy actions in the euro area? This is the focus of our work.

Common understanding amongst economists is that the price level is in general determined by the joint action of monetary and fiscal action. Yet the way the monetary and fiscal authorities interact is the product of institutional arrangements and historical circumstances.

Empirically, there is limited knowledge about how the combination of monetary and fiscal policy affects inflation and not only for the EMU. The reason is that this is a complex topic since there are multiple channels of interaction. Monetary policy, by affecting interest rates, output and inflation has an impact on the government’s budget constraint. The response of fiscal authorities via the adjustment of the primary deficit depends on the fiscal framework and the stabilisation objectives of fiscal authorities. The effect on inflation depends on the combined effects of fiscal and monetary actions as these affect the adjustment which is required to satisfy the intertemporal budget constraint of the consolidated government sector (central bank and governments). This is the consequence of the fact that the constraint is a binding identity which depends on inflation, returns on government debt and primary surpluses.

In the governance of the euro area, the central bank is an independent institution. As a consequence, the budget constraints of the central bank and governments must be thought as separate ex-ante. However – ex-post – what matters to understand the dynamics of inflation is the consolidated budget constraint of the central bank and the nineteen fiscal authorities. Therefore, if we want to understand the causes of the under-shooting of the inflation target since 2013 in the European Monetary Union (EMU), we need to consider how primary deficits and returns have responded to monetary policy.

In a recent paper (Reichlin, Ricco, Tarbé, 2021) we estimated empirically the response of fiscal variables, inflation and the market value of government debt to monetary policy changes affecting the short-term rate (traditional policy) or long-term rates (forward guidance or quantitative easing). Beside estimating VAR-based impulse response functions, we used the intertemporal budget constraint identity to obtain a decomposition of unexpected inflation (conditional on monetary policy) into several components: the primary deficit, returns on the market value of government debt, and output growth. We modelled this relationship using a newly constructed dataset for France, Germany, Italy and Spain and also Euro-Area aggregate data.

Our framework is inspired by Hall and Sargent (1997) and Cochrane (2019, 2020). Common to their approach is to start from the general government intertemporal budget constraint as an equilibrium identity linking the market value of the debt to future discounted primary surpluses.

From that budget constraint, one can obtain a linearized identity that, in words, is of the following shape:

Inflation (impact) – Nominal Returns (impact) =

– (cumulated Surplus + cumulated Growth)

+ (cumulated future Nominal Returns – cumulated future Inflation),

where each term is to be thought of as an unexpected change.

The intuition is that an unexpected contemporaneous increase in inflation – if not matched by a movement in contemporaneous returns – has to correspond to either a decline in the (cumulated) surplus to GDP ratios, or a decline in cumulated GDP growth, or a rise in the discount rates1. These adjustments in the aggregate can happen as a combination of symmetric or asymmetric changes at the country level.

Since this identity involves bond returns, inflation and fiscal variables, it can be used to learn about the fiscal-monetary adjustment dynamics in an otherwise unrestricted empirical model.

To apply this framework to the euro area we need to extend it to the case of a single central bank and multiple fiscal authorities.

If the euro area were a full federation, there would be a single federal issuance of treasury determining a unique yield curve which would be linked to the current and future inflation via the general budget constraint. If it were a monetary union of disjoint states with a common currency, each fiscal authority would be independently balancing their own budgets, taking as given the inflation controlled by the independent central bank.

A more realistic view of the euro area – albeit stylised – is the one in which inflation is determined by the aggregate fiscal and monetary stance, and the aggregate fiscal stance is the sum of the fiscal positions of individual states that may or may not balance their budget independently, and are bound by the common inflation rate. Yet, each country issue debt and faces different market rates (and returns), and hence there is no common yield curve and spreads among countries can open up. Such a description can accommodate different mechanisms such as divergences in the national inflation rates in the medium-run, and fiscal transfers across countries to help balancing out national fiscal imbalances. Whether such mechanisms operate or not is an entirely empirical matter.

This stylised view of the euro area informs our empirical exercise.

We identify the shocks in the model using a combination of sign restrictions, as in Uhlig (2005), and the recently proposed narrative sign restrictions of Antolin-Diaz and Rubio-Ramirez (2018). In addition to traditional sign restrictions, we constrain an expansionary conventional monetary policy shock (MP) to have a negative impact on the short- and long-term interest rates, a positive impact on output, and a positive impact on inflation and inflation expectations for the first three quarters (inflation moving by a larger amount). We separately identify the MP and unconventional monetary policy shocks (UMP) based on their differential impacts on the yield curve. The MP shock is assumed to move short term interest rates by a larger amount than long term rates, leading to a steepening of the yield curve. The UMP shock has the opposite effect on the slope. We also assume that monetary policy shocks are neutral and do not affect real GDP, in the long-run.2

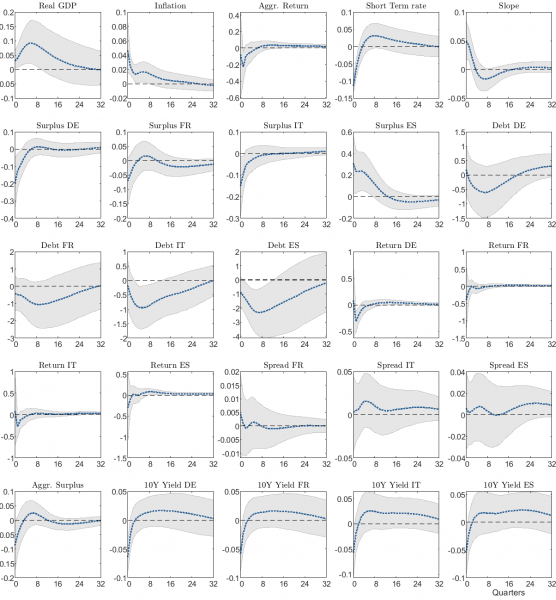

A first set of results pertains to conventional monetary policy (Figure 1). GDP and inflation respond as expected: there is a hump-shaped impact on GDP, peaking at about 0.1% in the second year, and an immediate impact on inflation and inflation expectations. In line with the transitory nature of the shock, the impact on long-term yields is both small in magnitude and short lived.

What is more interesting for our discussion are the responses of the fiscal variables. For the aggregate we estimate an immediate decline in the surplus-to-GDP ratio which, as shown in Figure 1, is driven by France, Germany and Italy, whereas Spain responds with a surplus. The value of debt-to-EA-GDP ratio falls for all countries in the first two years, although there is a high degree of uncertainty in these estimates.

Figure 1 – Impulse response functions to a one standard deviation conventional monetary policy shock (easing) in the euro area. The shock is small cut in the short-term interest rate, of about 10 basis points. The impulse response of real GDP is reported in level, i.e. as percentage deviation from the steady state. All other impulse responses are reported as annualized percentage-point deviations from the steady state. For details on the quarterly data construction and which variables enter the estimation, see appendix B of Reichlin et al (2021). Inflation and interest rates are in % (annualized). Slope is the German long-term interest rate minus the euro area short-term interest rate. Returns are nominal returns in % (annualized) on the portfolio of government debt, inferred from debt and surplus. Spreads are country long-term interest rates minus the German long-term interest rate. Debts are 400 times the logarithm of the following ratio: country debt over quarterly euro area GDP. Surpluses denote 400 times country primary surplus over quarterly euro area GDP, scaled by country debt over euro area GDP at steady state.

The response of the return on government debt is ambiguous since it is driven by both short- and long-term interest rate movements while sovereign spreads do not appear to react significantly to the conventional MP shock, indicating a symmetric transmission across the euro area.

To bring more insight to these results we can decompose unexpected inflation into various components using the intertemporal budget constraint identity. An unexpected increase in inflation has to correspond to a decline in the present value of surpluses, coming either from a decline in the surplus-to-GDP ratio, or a decline in GDP growth, or a rise in the discount rate. These adjustments in the aggregate can happen as a combination of symmetric or asymmetric changes at the country level.

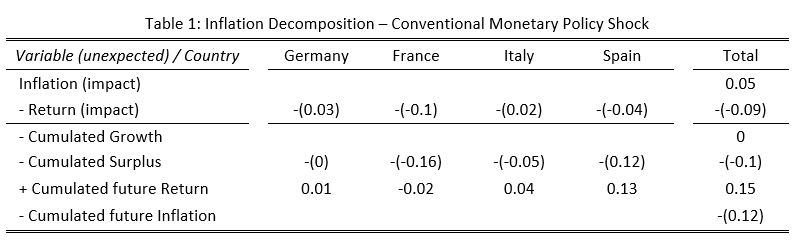

We report results on the decomposition in Table 1.

Table 1 – Unexpected Inflation decomposition in terms of changes to returns and future cumulated changes to growth, surplus, returns and inflation. The country columns display numbers weighted by country shares. For details on the quarterly data construction and which variables enter the estimation, see appendix B of Reichlin et al (2021). Inflation is in % (annualized). Returns are nominal returns in % (annualized) on the portfolio of government debt, inferred from debt and surplus. Surpluses denote 400 times country primary surplus over quarterly euro area GDP, scaled by country debt over euro area GDP at steady state.

The unexpected inflation decomposition reported in the table shows that the 10 basis points (bps) decline in the short-term rate corresponds to a small response in nominal returns characterized by a contraction in the short run of 9 bps, and then an increase by 15 bps in the long-run. Unexpected inflation jumps by 5 bps in the short run, and shows a cumulative increase of 12 bps in the long-run. Thus, the real discount rate term is 3 basis points, allowing a cumulated deficit of the same magnitude as -0.14 + 0.03 = -0.11 bps.

These results have to be understood as indicative since long-run estimates are necessarily imprecise due to the uncertainty in the assumptions on the level of the steady states.3 They point to a decomposition of unexpected cumulated inflation which is split by fiscal policy which eases in the same direction of monetary policy and a relatively muted response of returns on the market value of the debt. As we will see in the next section, this contrasts with the response to unconventional monetary policy.

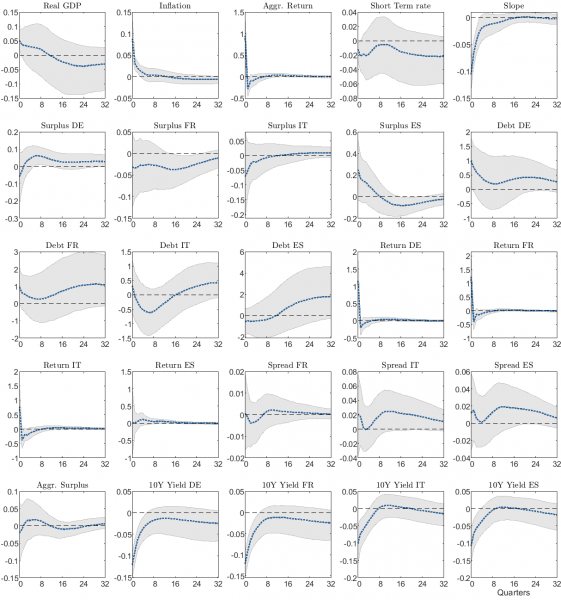

A second set of results for unconventional monetary policy is reported in Figure 2. We observe a small positive reaction of output and a sizable response of inflation on impact, yet both effects are less persistent than in the case of conventional shocks. The effect on the surpluses is negligible and not significant. While the value of the debt increases on impact for some countries, the response is not significant beyond the first period. This is associated with an unambiguous response in the returns on government debt, which explains the increase in the market value of the debt for Germany and France.

Figure 2 – The figure shows impulse response functions to a one standard deviation unconventional monetary policy shock (easing) in the euro area. A one standard deviation shock corresponds to a 10 basis points decline in the long-term average yield. The impulse response of real GDP is reported in level, i.e. as percentage deviation from the steady state. All other impulse responses are reported as annualized percentage-point deviations from the steady state. For details on the quarterly data construction and which variables enter the estimation, see appendix B of Reichlin et al (2021). Inflation and interest rates are in % (annualized). Slope is the German long-term interest rate minus the euro area short-term interest rate. Returns are nominal returns in % (annualized) on the portfolio of government debt, inferred from debt and surplus. Spreads are country long-term interest rates minus the German long-term interest rate. Debts are 400 times the logarithm of the following ratio: country debt over quarterly euro area GDP. Surpluses denote 400 times country primary surplus over quarterly euro area GDP, scaled by country debt over euro area GDP at steady state.

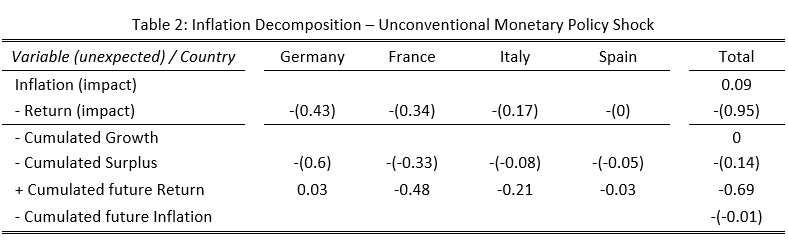

Table 2 – Unexpected Inflation decomposition in terms of changes to returns and future cumulated changes to growth, surplus, returns and inflation. The country columns display numbers weighted by country shares. For details on the quarterly data construction and which variables enter the estimation, see appendix B of Reichlin et al (2021). Inflation is in % (annualized). Returns are nominal returns in % (annualized) on the portfolio of government debt, inferred from debt and surplus. Surpluses denote 400 times country primary surplus over quarterly euro area GDP, scaled by country debt over euro area GDP at steady state.

The unexpected inflation decomposition reported in the table shows that the 10 basis points (bps) decline in the long-term rate due to the unconventional monetary policy shock corresponds to a large adjustment in the nominal returns which jump 95 bps in the short run, and contract by 69 bps in the long-run. Inflation movements are muted, about a half of what seen in the case of conventional monetary policy. We have a jump by 9 bps in the short run, and a cumulated decline by 1 bps in the long-run. Thus, the real discount rate term is -68 bps.

While in the case of conventional monetary policy we have seen a cumulated deficit in the long-run, here we have a cumulated primary surplus to GDP ratio which increases by 14 bps generating crosswinds in the aggregate.

The muted fiscal response conditional on an UMP shock is telling us that when that policy was active, i.e. since the 2008 crisis (first via targeted loans, then via forward guidance and asset purchases), fiscal authorities did not use the fiscal space afforded by the decrease in long-term rates. Overall, the response of the primary surplus to a monetary policy easing is insignificant in the short-run, while it seems to be positive in the long-run, unlike in the case of conventional policy. This long-run finding is mainly to be attributed to Germany.

These results come with two warnings. First, as we have seen, estimates are quite imprecise. Second, long run results are also sensitive to assumptions on the steady state, as already commented. This is a problem hard to address given the short sample and the evolving policy landscape.

In the euro area the empirical fiscal-monetary mix appears to vary depending on the conventional (i.e. affecting the short-term interest rate) or unconventional (i.e. shifting the long end of the yield curve) nature of the monetary policy shock.

Key in this difference are two factors: (i) the movement of the returns on the value of the debt, which depends on the change in yields at the relevant maturity, and (ii) the response of the primary surplus which depends on fiscal policy.

Nonstandard monetary policy has a much larger effect on returns since, given the average debt maturity, long-term yield changes have a higher impact on returns than changes in the short-rate. The long-run price level is lower than in the conventional policy case, and the primary surplus increases slightly.

The interpretation of this result is that, when unconventional monetary policy was implemented – post financial crisis – the combination of high legacy debt and fiscal rules constrained the fiscal response determining a situation in which the monetary and fiscal authorities worked against one another.

A key question is whether the more muted impact of non-standard monetary policies in the euro area in comparison with the US and the UK (see Hartmann and Smets, 2018) can be explained by the fact that fiscal policy since the financial crisis was cyclical and constrained by the fiscal rules in a situation of high public debt. In fact, a reasonable hypothesis is that a “conservative” fiscal policy at the effective lower bound may have been one of the causes of the persistent undershoot of the inflation target since 2012.

Paradoxically, when the economy was at the ELB, in a situation in which fiscal policy is more powerful than monetary policy, the responsibility for stabilization fell on the shoulders of monetary policy alone, while fiscal policy was generating crosswinds.

Going forward, the likelihood of recurrent large supply shocks like pandemics, or climate emergencies, suggest that spill-over of fiscal policy to inflation will be especially large and that fiscal policy will need to be used proactively.

Antolin-Diaz, Juan and Juan Francisco Rubio-Ramirez, “Narrative Sign Restrictions for SVARs,” American Economic Review, October 2018, 108 (10), 2802-29.

Bartsch, Elga, Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Giancarlo Corsetti, Xavier Debrun “It’s All in the Mix: How Monetary and. Fiscal Policies Can Work or Fail Together”. Geneva Reports on the World Economy 23, 2021.

Cochrane, John H, “The fiscal roots of inflation,” Technical Report, National Bureau of Economic Research 2019.

Cochrane, John H., “The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level”, Unpublished, 2020.

Draghi, Mario, “Unemployment in the Euro Area,” Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, Annual central bank symposium in Jackson Hole, European Central Bank 2014.

Hall, George J. and Thomas J. Sargent, “Interest rate risk and other determinants of post-WWII US government debt/GDP dynamics,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2011, 3 (3), 192-214.

Hartman, Philipp and Smets, Frank, (2018), The European Central Bank’s Monetary Policy during Its First 20 Years, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 49, issue 2 (Fall), p. 1-146.

Lagarde, Christine, “Monetary policy in a pandemic emergency,” Keynote speech by Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, at the ECB Forum on Central Banking, European Central Bank 2020.

Reichlin, Lucrezia and Ricco, Giovanni and Tarbé, Matthieu, Monetary-Fiscal Crosswinds in the European Monetary Union (May 1, 2021). CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP16138.

Schnabel, Isabel, “Unconventional fiscal and monetary policy at the zero lower bound,” Keynote speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Third Annual Conference organised by the European Fiscal Board on “High Debt, Low Rates and Tail Events: Rules-Based Fiscal Frameworks under Stress”, European Central Bank 2021.

Uhlig, Harald, “What are the effects of monetary policy on output? Results from an agnostic identification procedure,” Journal of Monetary Economics, March 2005, 52 (2), 381-419.

Cochrane (2019) then decomposes further the contemporaneous nominal return term, between a future inflation term and a future real discount rate term, by assuming a geometric maturity structure. Unexpected inflation has to correspond to a decline in expected future surpluses, or a rise in their discount rates.

We complement the restrictions on impulse responses with narrative sign restrictions, following Antolin-Diaz and Rubio-Ramirez (2018). In particular we assume that: (i) a contractionary (negative) conventional monetary policy shock happened on the third quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2011, being the single largest contributor to the unexpected movement in the short-term interest rate during those two periods; (ii) an expansionary (positive) unconventional monetary policy shock took place on the first quarter of 2015, and it was the single largest contributor to the unexpected movement in the term spread between the German long-term interest rate and the short-term interest rate during that period.