Two decades after its creation, Economic and Monetary Union finds itself at a crossroads. At its heart, a success: the common currency, the euro – 21 years old and already the world’s second-strongest currency. Over those two decades, monetary union has shown itself capable of continuing innovation, impressive in scope and depth. Nonetheless, even before the pandemic, it had become clear that more work was needed to complete the edifice of the union. In this article, we take stock of the monetary union’s achievements and argue that fresh thinking is needed to close the remaining institutional gaps. As we look towards the post-pandemic future, we need to reassess old paradigms and offer new solutions to old truths. We argue the post-pandemic agenda should focus on four areas: (1) monetary policy, (2) European fiscal infrastructure; (3) convergence and investment; and (4) financial markets, risk-sharing, and global positioning of the euro.

Two decades after its creation, the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) finds itself, once again, at a crossroads. Since the first euro was issued in January 2000, and especially in the decade after the global financial crisis, EMU had already adapted and evolved in a manner most would have thought impossible at the start. Now, as we emerge from the Covid pandemic crisis, it is continuing to chart new directions, reflecting the tectonic shifts that continue to affect the global economy and Europe, in particular.

Since the global financial crisis, developments like sub-par growth and investment rates, stubbornly low inflation, a continued secular decline of interest rates, and innovation in financial markets have upended traditional paradigms of monetary policy around the globe. Through it all, EMU’s crowning achievement, the euro, has managed to thrive. But despite its many achievements and successful reforms, it was clear even before the pandemic that more work was needed to complete the edifice of EMU. The pandemic and the deep economic crisis it caused put the spotlight on those remaining gaps. Yet it also highlighted something eminently positive: Europe’s capacity to act and to provide novel solutions.

In developing our ideas for the future of EMU, we will build on those achievements and gaps as we saw them at the eve of the pandemic. Yet we must also challenge some of our basic assumptions against the profound changes and new realities that have emerged in recent years. An overarching theme here, as in other policy areas, is that monetary policy will have to pay greater attention to policy interdependencies; the economic, social and political sustainability of solutions; and the common good of the Union.

As noted, the two decades since introduction of the euro have brought important achievements while also leaving many challenges yet to be met. Let us be clear: since it was launched in 2000, the euro has not only survived two seminal crises, but it is more “alive and well” than ever. We assess the success and imperfections of EMU under four broad headings: euro acceptance and resilience; price stability and convergence; institutional architecture; and the pandemic response.2

(1) Popular support and resilience

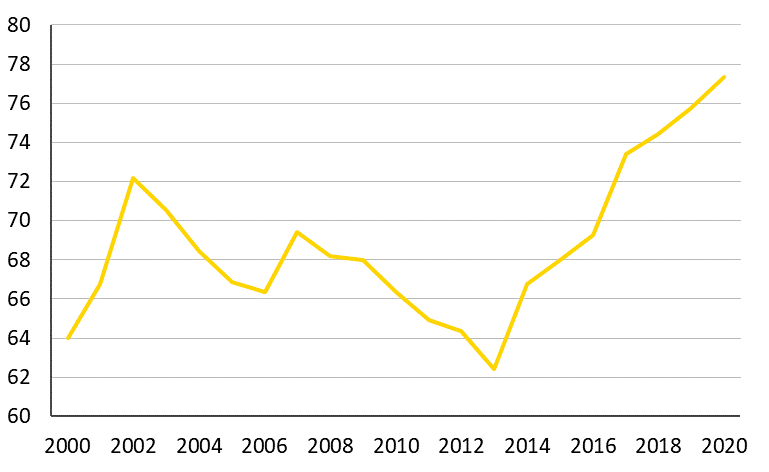

The euro area is now emerging from the most severe economic downturn of the last century, yet the euro is more popular than ever since its introduction 21 years ago. The most recent Eurobarometer survey shows that 79% of euro area citizens support “European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro” (see Chart 1).

Chart 1. Euro area citizen support for the euro (in %)

Source: European Stability Mechanism (ESM) calculations based on Eurobarometer (see below)/Haver Analytics, annual averages, population weighted national results.

Note: Share of positive responses for euro area citizens when asked whether they are “for” or “against” “A European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro”. Latest poll: European Union (April 2021), Standard Eurobarometer 94 – Winter 2020-21, Question B3.1 (page 133), Fieldwork Date February-March 2021.

And the euro area’s success is attractive beyond its borders: more European Union (EU) countries, such as Bulgaria and Croatia, would like to adopt the euro. Following years of reforms to comply with relevant standards, they have entered the euro area’s “waiting room”.3

This builds, of course, on the other elements of success such as low inflation, the removal of exchange rate fluctuations between member states, ease of travel, and the resilience of the common currency in global exchange markets. This has greatly facilitated domestic and foreign trade as well as financial transactions, reflected in the broad and increasing use of the euro domestically and internationally.

(2) Price stability and convergence

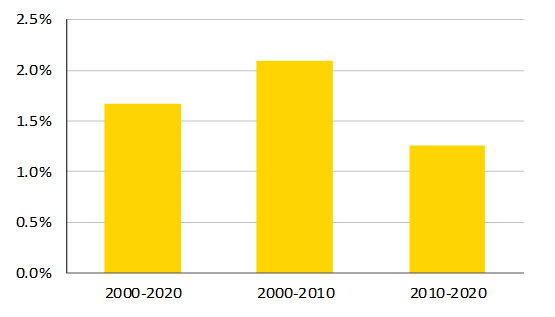

The European Central Bank (ECB) has succeeded in achieving its prime mandate, price stability, although inflation has remained below its objective over the past decade. Overall, inflation since 2000 has averaged 1.67% – not far off the ECB’s longstanding definition of price stability as close to but below 2%. That said, inflation over the past decade has been significantly below-target, averaging 1.25% since 2010 (see Chart 2). The shortfall can be explained by the fact that the euro area could not delink itself from the global trend decline in inflation and interest rates, and was hit by two major crises with deep recessions. Still, it is a concern and was a key issue calling for a review of the monetary policy strategy. The ECB recently completed its Strategy Review, as we will discuss below.

Chart 2. Euro area inflation: harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP)

Source: Eurostat, ESM calculations, averages for selected time periods.

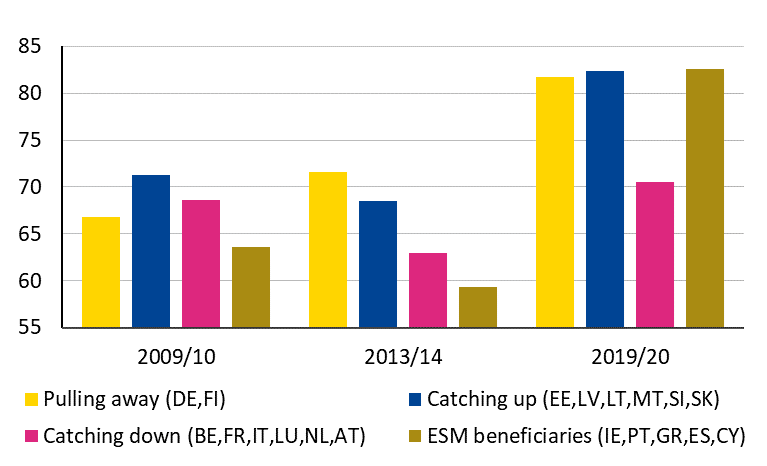

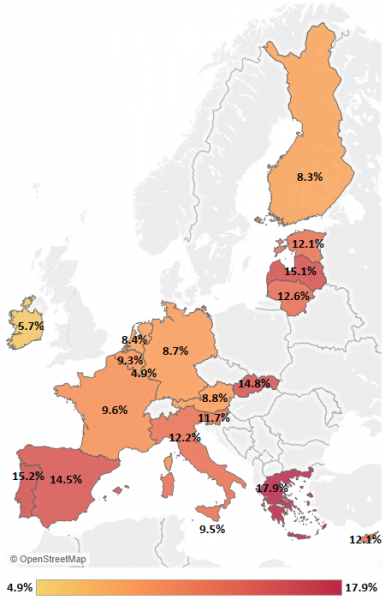

Economic convergence is important for sustained political support throughout the union. Indeed, EMU has supported the catching up and convergence of transition economies, and business cycles seem to have become more synchronised.4 Still, the record on convergence is mixed. While income disparity among euro area countries has declined significantly on average, some individual member states have fallen behind. Moreover, income divergence has increased within countries and across regions. In particular, a number of regions in “older” (non-transition) member states have experienced a widening negative income gap compared with the EU average. This lack of convergence across regions has created a political vulnerability for EMU, which is also visible in the varying support rate for the union among different countries and regions (See Chart 3). After the sovereign debt crisis, the attitude towards the euro improved significantly among ESM beneficiary member states, which experienced high growth periods following the ESM programme and related policy reforms.

Chart 3. Trust in the EU by country convergence

Source: ESM calculations based on European Commission.

Note: Group “pulling away” refers to countries with above-median GDP per capita in 2000 and above-median GDP growth from 2000 to 2020. Group “catching up” refers to below-median GDP per capita in 2000 and above-median growth from 2000 to 2020. Group “catching down” refers to countries with above-median GDP in 2000 and below-median GDP growth from 2000-2020.

(3) Institutions

The success of EMU is also attributable to the strength and independence of the ECB and significant institutional deepening on the regulatory and fiscal side. A number of these measures are taken at the EU level, but they contribute as well to the deepening of monetary union. The ECB’s commanding position as an independent central bank shaping economic and policy expectations in the euro area, the quality of its staff, tools and research, and the effectiveness of its actions to address two major crises are remarkable achievements. Moreover, the broad-based regulatory reforms and the creation of a European-level supervision and resolution framework after the past crisis have laid the groundwork for the high level of stability in the banking sector during the pandemic. That said, the record on financial sector integration is mixed, at best, as each country’s banking system still largely operates on its own and cross-cross border risk-sharing remains low. As discussed more fully below, this is a key shortcoming that hampers dynamic growth and innovation throughout the union, and is one of the key reform priorities for the period ahead.

When talking about institutional deepening, let’s not forget about the ESM – the crisis resolution mechanism created 10 years ago. The large financing packages provided to member states in difficulty, and the policy conditionality that accompanied them, helped those countries regain market access and address the macro and structural imbalances underlying the crisis. From a systemic viewpoint, it provided joint, solidarity support by the union, in a public risk sharing framework with elements of a central, fiscal capacity. Favourable lending conditions provided significant fiscal space and budgetary savings for countries receiving ESM support.

(4) The pandemic response

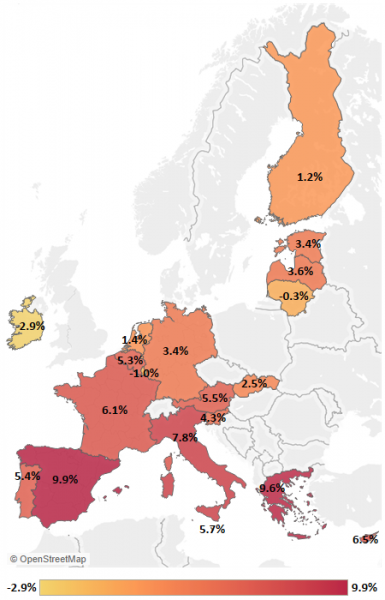

The European policy response taken in the pandemic – both the first package incorporating measures by the ESM, European Investment Bank and the European Commission, and the second phase leading up to Next Generation EU (NGEU) – have demonstrated a willingness and capacity of the union to act quickly, jointly, in solidarity, and on a large scale. The size of support is larger for countries that suffered more from a common shock and those with lower per-capita income (see Chart 4). This is a crucial sign of ‘political maturity’ of the union, which has clearly helped preserve the euro area’s integrity through the crisis and further buttressed the euro’s popularity.

Chart 4. Economic loss in 2020, in % of GDP (left-hand side), and Recovery and Resilience Facility grants and loans maximum allocations (right-hand side)

|

|

Source: Ameco, Darvas, Z. (2021), European Commission.

Note: The calculations of the total Recovery and Resilience Facility support include a maximum amount of loans potentially available to each Member State equal to 6.8% of 2019 Gross National Income. The calculations of the expected economic loss are computed for 2020, with 2019 as a base. Some Member States have recorded a minor recovery and therefore a negative loss.

The impressive scope and depth of institutional innovation we have experienced over the past decade – including the EU’s unprecedented Covid crisis response, which has ushered policies into new, untested territory – should open the door to fresh thinking on how to tackle the remaining gaps. We need to reassess old paradigms, such as on debt sustainability, joint European fiscal action, and the coordination of monetary and fiscal policies.

EMU faces a number of challenges that will shape the post-pandemic policy agenda. Many of these challenges are global, including the need to revive low growth, manage ageing populations, reduce inequality and regional divergences, and address climate change. Others are Europe-specific, such as reforming our fiscal rules and surveillance, further integrating banking systems and capital markets, strengthening the international role of the euro, and balancing national and European interests.

To tackle these challenges effectively, the post-pandemic environment will benefit from greater focus on common goals as well as a more holistic view of policy complementarities and coordination across policy areas. While doing this, we must not discard basic economic principles, such as the need to respect budget constraints. Instead, the point is to recognise changed economic realities – such as low-for-long interest rates and climate change – and incorporate them into policy-making, with focus on interdependencies and on economic, social, and political sustainability.

The post-pandemic agenda for strengthening EMU further should focus on four areas: (1) monetary policy, including its relationship with fiscal and sovereign crisis management; (2) European fiscal infrastructure; (3) convergence and investment; and (4) financial markets, risk-sharing, and global positioning of the euro.

I. Monetary policy and supportive policy settings

The ECB’s new monetary policy strategy sets out a clear framework for monetary policy over the medium-term, taking into account the potential risks from the lower bound on interest rates, financial imbalances, insufficient support from fiscal and other macro-structural policy settings, and climate change. It thus clarifies the setting for monetary policy while also pointing to the agenda for other key policies required to ensure the continued success of EMU.

ECB strategy review

The ECB recently approved its new monetary policy strategy, which includes a number of clarifications as well as new directions. It adopted a symmetric 2% inflation target over the medium term, and confirmed the harmonised index of consumer prices as the appropriate price measure. The new strategy is clear in its focus on euro area inflation, medium-term orientation, and primary tools; and it recognises the potential risks to medium-term price stability from financial imbalances and climate change.

Interdependencies and wider policy implications

The strategy emphasises the pervasive role of macro-financial linkages, and the importance of integrated economic, monetary, and financial analysis in assessing and managing risks to the medium-term inflation outlook. This highlights one of the key lessons from recent years: successful monetary policy – particularly near the zero bound – needs the support of strong macro, financial, and structural policies. This has been taken into account in the repeated calls by the ECB in recent years for a supportive fiscal policy stance and growth-boosting reforms to complement its policy actions. In several respects, it moves away from the axiomatic view of strict separation of monetary and fiscal policy with greater emphasis on policy coherence and complementarity.5

Boosting potential growth and convergence

No policy arrangement can last unless it serves the needs of its constituents – in other words, nothing works without sustainable growth or if too many people are left behind. Hence, the critical importance of NGEU as a recovery plan that combines the provision of large amounts of resources with growth-boosting reforms in member countries.6 Addressing the large and growing divergences, especially among regions, and lifting growth in lagging countries in the euro area, is critical for making the monetary union more sustainable, resilient, and serving the needs of all its citizens. A recent paper by ESM staff examined this issue and presented some policy recommendations.7

Two decades after its creation, Economic and Monetary Union finds itself at a crossroads. At its heart, a success: the common currency, the euro – 21 years old and already the world’s second-strongest currency. Over those two decades, monetary union has shown itself capable of continuing innovation, impressive in scope and depth. Nonetheless, even before the pandemic, it had become clear that more work was needed to complete the edifice of the union. In this article, we take stock of the monetary union’s achievements and argue that fresh thinking is needed to close the remaining institutional gaps. As we look towards the post-pandemic future, we need to reassess old paradigms and offer new solutions to old truths. We argue the post-pandemic agenda should focus on four areas: (1) monetary policy, (2) European fiscal infrastructure; (3) convergence and investment; and (4) financial markets, risk-sharing, and global positioning of the euro.

Appropriate fiscal support while avoiding fiscal dominance

As monetary policy focuses on the medium-term inflation target, fiscal policy – at national and euro area-levels – plays an enhanced role in supporting demand, especially when interest rates are near the lower zero bound. Then fiscal policy has a role in also buffering aggregate exogenous shocks. In this context, monetary policy needs to ensure appropriate financing conditions to allow for the proper operation of the monetary policy transmission mechanism. But it cannot be the safeguard of favourable financing conditions for the sovereign under all circumstances. Country risk should be addressed by appropriate macro, structural and macro-prudential policies at the country level. Official financial support (lender-of-last-resort), if needed, should remain conditional on such appropriate country policy settings. For euro area countries this role has been given to the ESM under its enhanced mandate, including joint responsibility with the European Commission for future programme design and monitoring. ESM instruments allow for setting policy conditionality according to the needs of the specific case. We are well on track to implementing the enhanced mandate, along with the ongoing ratification of the new ESM Treaty, and ensuring the ESM is fit and ready for purpose.

II. A new European fiscal policy framework – an important complement for monetary union

In a nutshell, we need to develop our fiscal framework and instruments so that they create the right conditions not only for debt sustainability, but also for sustained growth and stabilisation. The new institutional framework will need a stronger role for both national and EU-wide fiscal policies. They can build on existing structures, yet need to be bolder and more comprehensive in design and implementation.

Fiscal rules

There is widespread – albeit not unanimous – agreement that the EU fiscal rules should be reformed and streamlined when the period of suspension ends (currently through 2022). Of course, it remains a basic truth that public finances must be sustainable. Looking at the current macro-environment, we believe that governments should be able to meet their current and future payment obligations without exceptional financial assistance or going into default.

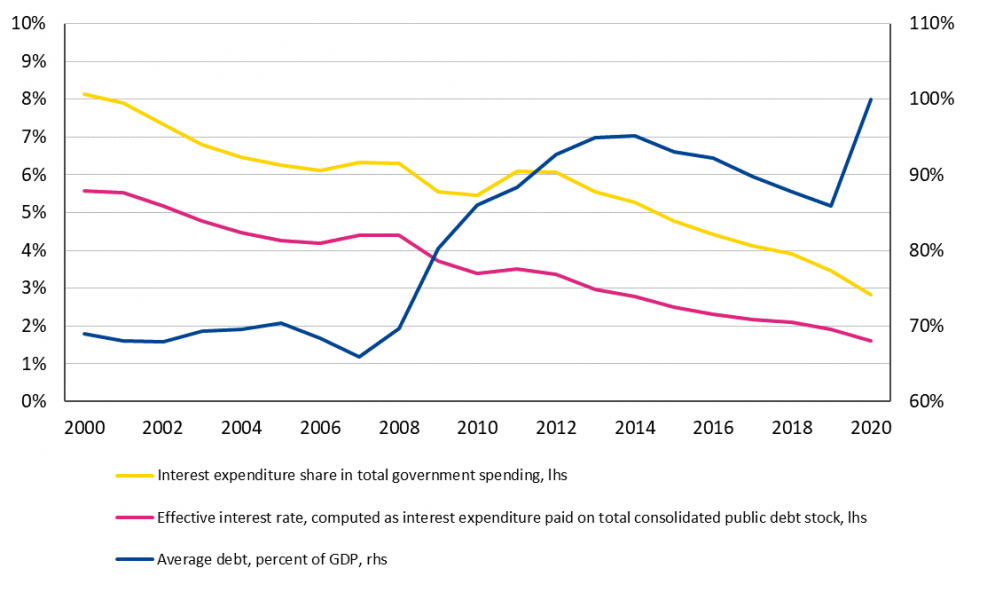

What has changed is that the debt carrying capacity of advanced economies has increased substantially, given low-for-long interest rates, innovations in financial markets, and improvements in countries’ debt management capabilities. Interest payments on public debt have declined sharply as a share of total government expenditures, despite the rise in debt levels. Like others, we have come to the conclusion that a simplified EU fiscal framework could be built around a 3% deficit limit and modified reference value for the debt-to-GDP ratio (see Chart 5). These headline values would be operationalised by an expenditure rule and a debt adjustment path.8

Chart 5. Euro area debt and effective financing costs

Source: ESM calculations based on European Commission, Eurostat.

As economic growth plays a key role in reducing government debt burdens, the redesigned fiscal rules need to allow for productive, growth-enhancing public investment. Sustainable fiscal adjustment requires growth and social cohesion, hence the importance of growth-friendly fiscal policies that pay attention to the social impact, investment needs, and long-term growth determinants such as climate change and technological progress. Growth-enhancing fiscal policies can be achieved through an improvement in the quality of public finances, and it does not per se require higher deficits.

Stabilisation facility

National fiscal policies often fail to build sufficient buffers during upswings, which constrains the ability to provide stimulus – or even leads to a pro-cyclical (contractionary) stance – in a downturn. It would therefore be practical to complement the reformed framework of EU fiscal rules with a new fiscal stabilisation instrument, to help address country-specific shocks, especially for sharper downturns and more vulnerable countries. As the past experience has shown, national fiscal policies may simply be overburdened in view of the amplitude of the downturn, and this becomes even more prevailing if the monetary policy support which can be expected is constrained in a very low interest rate environment.

There have been many ideas and proposals for how such a stabilisation instrument could work.9 It could take the form of a euro-wide unemployment insurance scheme, a so-called rainy day fund, an ESM credit line, or a more informal system of transfer payments related to fluctuations in unemployment. The goal would be the same: to help smooth intra-EU cyclical fluctuations in an enhanced, well-circumscribed, public-risk sharing framework – and thereby further strengthen EMU. A stabilisation facility would not require a central budget, which implies annual spending. It could be based on a revolving fund, upon which countries draw when needed, and which avoids continuous transfers.

III. NGEU: convergence and investment

The NGEU recovery package aims to help Member States repair the economic and social damage from the pandemic. It also supports the transition to green, digital, sustainable growth and fosters social and territorial cohesion.

NGEU is an EU-wide instrument, but in the unfolding European pandemic support it also contributes to deepening EMU. It is a one-off measure and not a permanent tool. Still, it points toward possible future union-wide solutions to promote convergence and the transformation of our economies, for example, through an enlarged EU budget based on common taxation.

There are two principles in the current setting that should be preserved:

NGEU for the first time creates positive incentives for reforms for participating EU countries. Closely tied to the European Semester, this will positively affect the implementation of country-specific recommendations. So far the European macroeconomic surveillance and adjustment framework was largely built on political, and hypothetically even financial, sanctions which were rarely invoked. Positive incentives can strengthen compliance and reform efforts.

And second, focusing on “green taxation” and external trade and transactions is consistent with the EU’s competencies and common objectives. This consistency supports the political clarity of roles and the legitimacy of the measures. On that account we welcome that the current proposals for new own- resources of the EU include union-wide carbon emission-related levies. They recognise that effective carbon pricing is by far the most effective mechanism to promote the transition towards a net-zero carbon emission economy.10

IV. Financial markets, private risk-sharing and the euro

Financial markets in Europe have come a long way since the global financial crisis. Banks, in particular, have played a crucial role as positive shock-absorbers during the pandemic – in contrast to their shock-amplifying role in the great financial crisis. This has been achieved thanks to the broad and intense policy efforts to address the legacies of the crisis and fortify the system.11

Nevertheless, European financial markets remain segmented, heavily bank-focused, and hampered by uncoordinated and, at times, inefficient debt resolution systems. Weak profitability, limited market size, and inefficient and unclear regulations add to the constraints. As a result, many European financial institutions are falling behind, private-sector risk-sharing is limited12, and capital formation and entrepreneurial dynamism are stunted.

This is particularly relevant now, as we are looking to restart our economies, boost investment, and aim for greener, more digital, and more resilient growth. The strong public spark that NGEU is providing must also reach private enterprises, which will inevitably have to be the backbone of future growth.

It is, therefore, a priority that we further progress toward integrated financial markets across the monetary union, with appropriate safeguards for financial stability. European leaders and the European Commission have laid out a twin-track agenda toward this goal, i.e. banking union and capital markets union. Both will help to strengthen the international role of the euro.

Banking union

Completing banking union is vital given the central role the banking sector needs to play in financing the post-pandemic recovery. A crucial step in completing banking union is the introduction of the ESM backstop to the Single Resolution Fund next year. This backstop serves as a supplemental safety net as it can lend funds to the Single Resolution Fund to finance a resolution in case failing banks deplete the Fund’s resources. A strong, well-financed, and transparent bank resolution mechanism provides confidence to markets, prevents ripple effects for other financial institutions, and helps to protect people’s deposits. The backstop will also contribute to the robustness and resilience of EMU as a whole.

Additional reforms are needed to complete banking union, and the euro-finance ministers (Eurogroup) have been working on four key elements: a European Deposit Insurance Scheme, cross-border integration, the crisis management framework, and the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures. Much progress has been made toward solutions in all four areas in preparatory work streams; however, political agreement among member states has so far eluded us.

Beyond these areas, countries should look at national insolvency frameworks. Efficient and more convergent corporate insolvency frameworks will enhance economic resilience, strengthen the business environment and private investment, and support deeper financial integration – benefiting banking union and as well as capital markets union.

Capital markets union and equity finance

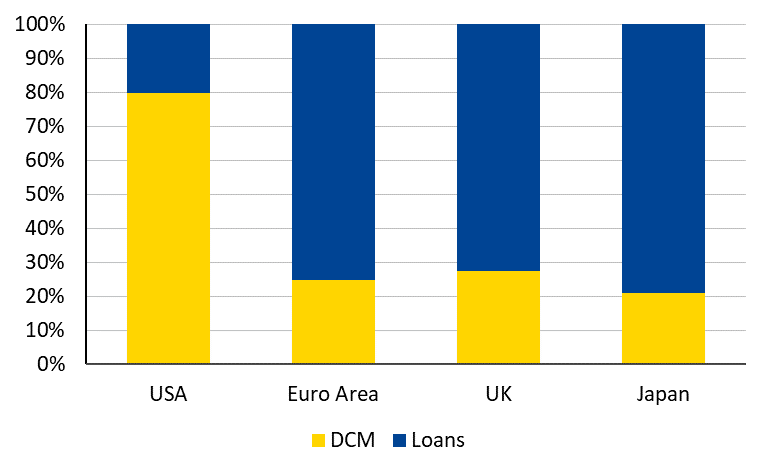

As bank financing, mostly loans, is the main source of financing for small- and medium-sized enterprises, completing banking union is vital for supporting Europe’s recovery – but we cannot stop there. Capital markets union has the potential to change the current inefficiencies in the allocation of savings in a highly fragmented EU financial sector, which hampers investment, innovation, and long-term growth. In comparison with the US, the EU lags behind in terms of use of equity to finance firms, as well as the dynamism of venture capital and initial public offerings, IPOs. Corporate credit is largely provided by banks (see Chart 6).

Chart 6. Debt capital markets (DCM) and loan financing of non-financial corporations

Source: SIFMA Capital Markets Fact Book 2021.

Some countries may emerge from the crisis with too much debt, and the resulting need to deleverage risks would hold back investment. Standard loan financing is often not available to start-ups that are inherently more risky, and there is a link between start-up activity and the number of mature, large, innovating firms that transform industries and boost growth. Therefore, we need to strengthen equity or equity-type financing. In the US there is more equity investments at an earlier stage of companies and the country now has over 400 so-called unicorns13 compared to about 100 in Europe. Tech firms, which receive a lot of early stage capital, have been growing at a fast pace and now dominate the US equity markets, while they are comparatively small in Europe14.

In the medium term, the integration of capital markets will facilitate cross-border investments, increase risk-sharing, and open up new financing options for companies. This will help sustain growth going forward and boost investment in a greener and more digital economy.

Strengthening European capital markets supervision will boost the attractiveness of the European market for international investors. This calls for steps to facilitate securitisation, support equity finance, improve market access for small firms, and enhance the safety of market infrastructure and regulatory transparency. A safe digital infrastructure, which should eventually include a digital euro, will add to the attractiveness of the European market and the euro.

International role of the euro

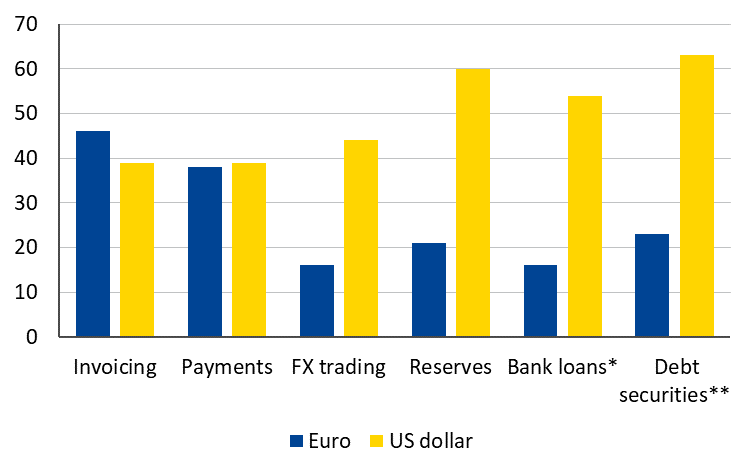

The euro’s international role has come a long way, but still has some distance to go – as a recent ESM staff discussion paper documents.15 Just two decades after its creation, the euro is now the world’s second-most important currency, especially for payments of goods and services where it already rivals the US dollar – while the dollar still reigns supreme in financial assets and flows (see Chart 7).

Chart 7. Global share of the US dollar and the euro in %

Source: Strauch and Hudecz (2021).

Notes: *Bank loans include cross-border loans denominated in a foreign currency (i.e. currencies foreign to bank location country); **Debt securities include securities that are issued in a currency other than that of the borrower’s residency.

Strengthening the international role of the euro would benefit the euro area and its citizens by supporting stable financing conditions, attracting investors, helping to finance the post-pandemic recovery, and preparing our economy for the future. The inherent, gradual move towards a multipolar global system is also welcome, and a strong role for the euro in such a system is essential, from economic, financial, foreign-policy, and national-security perspectives.

European policy makers have recognised the importance of the topic, which was high on the agenda of the Euro Summit earlier this year. Fundamentally, strong and credible European institutions, a strengthening euro area economy, and stability of the financial system will underpin the international role of the euro. Moreover, the Recovery and Resilience Facility under the NGEU will sharply expand the pool of euro-denominated safe assets, which can serve as an anchor for euro-denominated debt markets, where the euro lags substantially behind the dollar. The euro will also draw strength from enhanced crisis management, thanks to the ESM’s new role as backstop for the Single Resolution Fund, and from the focus of the NGEU package on digital transformation and green finance.

Looking ahead, EMU can become a well-tuned ‘concert of policies’, national and European, supporting dynamic, sustainable growth for the well-being of citizens across the euro area. EMU can act as an agent of convergence and stability, bringing along the laggards, helping those in temporary difficulties, and giving incentives and resources for transforming the euro area economy toward green, digital, sustainable growth. Integrated, European financial markets will offer ample funding for dynamic, innovative, and environmentally sustainable investments, guided by monetary and prudential policy settings that deliver around 2% inflation on average and contribute to financial stability.

Therefore, we believe that the following priorities should inform a concrete policy agenda for the next year and a half:

Amendola, A., Di Serio, M., Fragetta, M. and Melina, G., “The Euro-Area Government Spending Multiplier at the Effective Lower Bound”, IMF Working Paper 19/133, International Monetary Fund, 2019.

Beblavy, M. and Lenaerts, K., “Stabilising the European Economic and Mone-tary Union: What to expect from a common unemployment benefits scheme?” CEPS Research Report No 2017/02, February 2017.

Beblavy, M. Gros, D. and Maselli, I., “Reinsurance of National Unemployment Benefit Schemes,” Centre For European Policy Studies, No. 401. January 2015.

Beetsma, R., Cima, S. and Cimadomo, J., “A minimal moral hazard central stabilisation capacity for the EMU based on world trade,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP12600, January 2018.

Bianchi, F. and and Melosi, L., “The dire effects of the lack of monetary and fiscal coordination,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Elsevier, vol. 104(C), pages 1-22, 2019.

Bianchi, F., Faccini, R. and Melosi, L., “Monetary and Fiscal Policies in Times of Large Debt: Unity is Strength,” NBER Working Papers 27112, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc., 2020.

Bianchi, F., Melosi, L. and Rogantini, A., “Who is Afraid of Eurobonds?,” forthcoming in 2021.

Borgioli, S., Horn, C.-W., Kochanska, U., Molitor, P., Mongelli, F., P., Mulder, E., Zito, A., “European financial integration during the COVID-19 crisis”, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 7/2020.

Brandolini A., Carta, F. and F. D’Amuri, “A Feasible Unemployment-Based Shock Absorber for the Euro Area,” IZA Policy Papers 97, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), 2015.

Capella-Ramos, J., Checherita-Westphal, C. and Leiner-Killinger, N., “Fiscal transfers and economic convergence,” Occasional Paper Series 252, European Central Bank, 2020.

Carnot, N., M. Kizior and G. Mourre, “Fiscal stabilisation in the Euro-Area: A simulation exercise,” No 17-025, Working Papers CEB, Universite Libre de Bruxelles, 2017.

Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M. and Rebelo, S. “When is the government spending multiplier large?” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 119, 2011.

Coenen, G., Erceg, C. J., Freedman, C., Furceri, D., Kumhof, M., Lalonde, R., Laxton, D., Linde, J., Mourougane, A., Muir, D., Mursula, S., de Resende, C., Roberts, J., Roeger, W., Snudden, S., Trabandt,M. and Veld, J. I. “Effects of fiscal stimulus in structural models”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 4, 2012.

Darvas, Z. “Next Generation EU payments across countries and years”. Bruegel, blog post, August 2021.

Delbecque, B., “Proposal for a Stabilisation Fund for the EMU,” CEPS working document No. 385, October 2013.

Diaz del Hoyo, J.L., Dorrucci, E., Heinz, F.F. and Muzikarova, S., “Real convergence in the euro area: a long-term perspective,” Occasional Paper Series 203, European Central Bank, 2017.

Dolls, M., Fuest, C., Neumann, D. and A. Peichl, “A Comparison of Different Alternatives using Micro Data,” International Tax and Public Finances, January 2017.

Dullien, S. “A euro-area wide unemployment insurance as an automatic stabilizer: Who benefits and who pays?” Social Europe, December 2013.

Eggertsson, G. B. “What fiscal policy is effective at zero interest rates?” in Acemoglu D. and Woodford M. (eds), NBER Macroeconomics Annual, vol. 25, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010.

Enderlein, H., Guttenberg, L. and J. Spiess, “Blueprint for a cyclical shock insurance in the euro area,” Jacques Delors Institute, September 2013.

European Central Bank, Strategy Review, July 2021.

European Commission: Recovery plan for Europe, July 2020.

European Commission, Standard Eurobarometer 94, Winter 2020-2021.

European Fiscal Board, “Annual Report 2018”.

European Fiscal Board, “Annual Report 2020”.

European Parliament, “The Euro at 20: Successes, Problems, Progress and Threats”, 2019.

Furceri, D. and Zdzienicka, A., “The Euro Area Crisis: Need for a Supranational Fiscal Risk Sharing Mechanism?” IMF Working Paper 13/198, 2013.

Franks, JR, BB. Barkbu, R. Blavy, W. Oman, and H. Schoelermann, “Economic Convergence in the Euro Area: Coming Together or Drifting Apart?” IMF Working Paper 18/10, 2018.

Giovannini, A., Horn, C.-W., Mongelli, F.-P., “An early view on euro area risk-sharing during the COVID-19 crisis”, VOXEU, January 2021.

Hudecz, G., Moshammer, E., Raabe, A., Cheng, G.: “The Euro in the World”, ESM Discussion Paper 16, March 2021.

Hudecz, G., Moshammer, E., and Wieser, T., “Regional disparities in Europe: should we be concerned?” ESM Discussion Paper 13, July 2020.

Ignaszak, H., Jung, P., Kuester, K., “Federal Unemployment Reinsurance and Local Labor-Market Policies”, ECONtribute Discussion Paper No. 040, November 2020.

Lenarčič, A., and K. Korhonen, “A case for a European rainy day fund,” ESM Discussion Paper 5, November 2018.

Martin, P., Pisani-Ferry, J., Ragot, X., “Reforming the European Fiscal Framework,” French Council of Economic Analysis. No. 63. April 2021

Miyamoto, W., Nguyen, T. L. and Sergeyev, D. “Government spending multipliers under the zero lower bound: evidence from Japan”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 10, 2018.

Parry, I., “Putting a Price on Pollution. Why a Carbon Tax Makes Sense”. IMF Finance and Development, Vol. 56, No. 4, December 2019.

Ramey, V. A. and Zubairy, S. “Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: evidence from U.S. historical data”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 126, 2018.

Smets, F. and Beyer, R., “Labour market adjustments in Europe and the US: How different?,” ECB Working Paper Series 1767, 2015.

Strauch, R. and Hudecz, G., “Strengthening the international role of the euro”, ESM blog, March 2021.

The views expressed in this note are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

For a summary of EMU achievements see European Parliament (2019).

“Euro area waiting room”: countries join the Exchange Rate Mechanism II, which is a system for managing exchange rate fluctuations, smoothing the path of entry into the single currency.

See the discussion in Smets & Beyer (2015), Diaz del Hoyo et al. (2017), Franks et al. (2018), Hudecz et al. (2020) and Capella-Ramos et al. (2020) among others.

This view is backed by substantive academic literature. A vast number of theoretical (Eggertsson (2011), Christiano et al. (2011) and Coenen et al (2012)) and empirical studies (Ramey and Zubairy (2018), Miyamoto et al. (2018) and Amendola et al. (2019)) illustrate that the effectiveness of the fiscal policy increases dramatically when the monetary policy is constrained by the ZLB (passive collaboration). There is also an emerging literature (Bianchi and Melosi 2019, Bianchi et al. (2020) and Bianchi et al. (2021)) that views the monetary and fiscal policy reaction functions to be regime-dependent and argues in favour of fiscal monetary policy (active) coordination during large recessions.

European Commission: ‘Recovery plan for Europe’, https://www.suerf.orgwww.ec.europa.eu

Hudecz, G., Moshammer, E., Wieser, T (2020), Regional Disparities in Europe: should we be concerned? ESM Discussion Paper 13, July 2020.

EFB (2020), EFB (2018), Martin et al. (2021).

A number of concrete models have been proposed in the last decade, e.g. Dullien (2013), Dolls et al. (2017), Beblavý and Lenaerts (2017), Beblavý et al. (2015), Brandolini et al. (2015), Enderlein et al. (2013), Delbecque (2013), Furceri and Zdzienicka (2013), Carnot et al. (2017), Beetsma et al. (2018), Lenarčič and Korhonen (2018)and Ignaszak, Jung and Kuester (2020).

See, for example, Ian Parry: Putting a Price on Pollution. Why a Carbon Tax Makes Sense. IMF, Finance and Development, December 2019, Vol. 56, No. 4.

Giovannini, A., Horn, C.-W., Mongelli, F.-P., An early view on euro area risk-sharing during the COVID-19 crisis, VOXEU 10 January 2021, Available at: An early view on euro area risk-sharing during the COVID-19 crisis | VOX, CEPR Policy Portal (voxeu.org)

Borgioli, S., Horn, C.-W., Kochanska, U., Molitor, P., Mongelli, F., P., Mulder, E., Zito, A., (2020), European financial integration during the COVID-19 crisis, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 7/2020. Available at: European financial integration during the COVID-19 crisis (europa.eu)

Privately-owned start-ups with over €1 billion valuation. Source of unicorn count: various websites providing data on unicorns by country and regions (including cbinsights.com real-time unicorn tracker, traxn.com, statista.com).

The largest five companies in the US are now technology companies and have a combined market cap of €9.2 trillion while the five biggest technology companies in Europe are worth €630 billion.

Hudecz, G., Moshammer, E., Raabe, A., Cheng, G.: “The Euro in the World”, ESM Discussion Paper 16.