Often members of Central banks Boards are divided by commentators between hawks and doves. Christine Lagarde announced her willingness to be a “owl”, symbol of money and… wisdom in the ancient Greece. Christine Lagarde‘s turn towards the quality required to efficiently organize the decision making process is especially illuminating when used to analyze the relationship between the gender balance in central banking, the transmission of monetary policy and women economic concern. Against this background, the extreme gender imbalance in central banking impedes decisions makers to be as wise as one could hope and expect. Central banking remains a man’s world; since the creation of the ECB, 93 % of decisions makers in the governing council were male. The “listening exercise” of the ECB as well as the surveys we did in France, show that women feel less concerned by economic and monetary policies. They also focus on other issues than men, more tangible such as social inequalities or purchasing power. Even if it is difficult to determine if women behave differently than men in Monetary committees because of their gender or because of different life history, occupation and education, a more inclusive central banking may help to take better decisions and hence better transmit monetary policy.

1. It’s a man’s world with a glass ceiling slow to crack

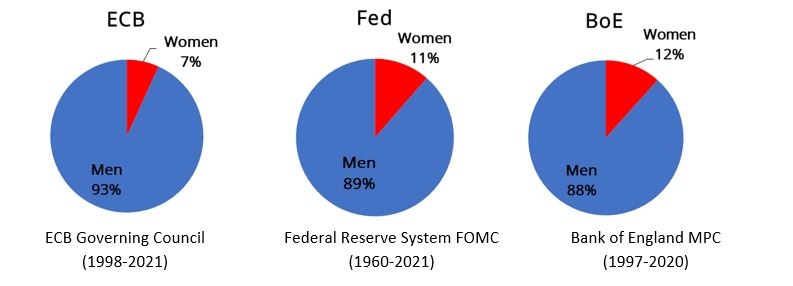

At the top, central banking has been and is still in 2021 a man’s world. Decisions were taken and are still taken by men and prepared by male top managers. Since the creation of the ECB to today, women held 7% of the seat of the Governing Council, a percentage that is slightly lower than in the Federal Reserve System or the Bank of England where women have held respectively 11% et 12% of the seats of the Federal Open Market Committee or the Monetary Policy Committee, see Chart 1. In the first 23 years of existence of the Eurosystem, Chrystalla Georghadji is the only woman to have acted as a Governor of a national central bank, in Cyprus, between 2014 and 2019. Since she has left, there is no more female governor (only the Board includes two women, Christine Lagarde and Isabel Schnabel). The figure is not that different for the top managers, though the situation is slowly improving. To take the example of Banque de France, women hold 30% of the top management positions against 21% in 2012 despite the fact that 46% of the staff is actually a woman.

The gender share in central banking is especially low when compared to the level achieved in national and local assemblies or in the governments of the countries of the European Union.2 It is also much lower than the gender share of European listed companies. To add some pessimism, the glass ceiling in expert groups seems slower to crack, as shown by the large imbalance in national dedicated COVID-19 task forces reported by the 2021 EU report on gender equality.3

Chart 1: A hard “glass ceiling” in monetary policy committees

Source: Istrefi K and G. Sestieri, 2018, “Central banking at the top: it’s a man’s world”. Banque de France blog, Updated with data up to 2021.

2. Do women economic concern differ from men’s view?

It is always dangerous to generalize. However women tend to have differing views from men on economic and monetary matters, maybe less because they are women but because as women they are often less educated, less paid and still in charge, more than men, of housekeeping. This difference was once again confirmed by the various events organized this year by the ECB and the national central banks of the Eurosystem in the context of the ongoing Strategy Review of the Eurosystem.

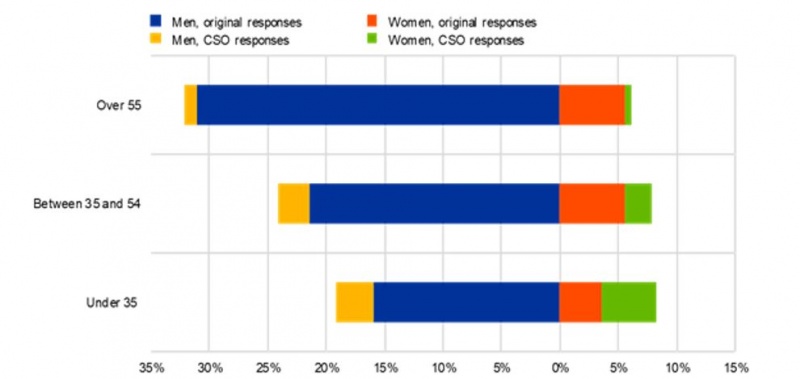

At the European level, the ECB launched an “ECB Listens Portal”, encouraging the general public to express their views on a range of issues. As usually found by the academic literature on gender, the respondents under-represents women and young: 22% of respondents were female (but mostly young, which is encouraging). And when women expressed their concerns, they are more vocal on issues such as the declining purchasing power, the worsening economic outlook, unemployment and job precariousness, climate change and growing inequality and poverty (see chart 2).

In France, according to the survey conducted by Banque de France in its « Banque de France listens » event, conducted over 5 000 French people, the results also confirm some of the previous trends on women. Unsurprisingly, respondents working in the financial sector and men were considerably more likely to admit to having sound knowledge of the ECB and NCBs. As in the ECB survey, women are more worried than men about the economic situation, they put social exclusion and poverty among their top economic priorities (44% vs 36% of men) and they are less likely to report basic or very good knowledge of monetary policy (4% vs 11% of men).

Two consequences follow.

Firstly, men and women have diverging views and the difference in their perceived view on the knowledge of monetary policy shall make them pay attention to different type of monetary policy news. As underlined by Isabel Schnabel from the European Central Bank, “It’s really about equal opportunity, not equal results.”4 Following this point of view, a highly imbalanced gender share in a central banking committee may, at least sometimes, hinder the efficiency of the aggregation of diverse views and therefore complicate or slow the transmission of monetary policy as well as the introduction of new topics at the agenda (climate, inequality, gender).

Second, a high gender imbalance in central banking is worrying for ethical reasons. Women form a diverse pool of talents. Aging societies cannot afford to waste these. As illustrated by the Covid19 outbreak, they were on average more exposed to the virus, from hospitals to nursery homes, schools or grocery stores. They also suffer relatively more from the constraints imposed by the sanitary situation, both in terms of their ability to balance their professional and personal life when schools closed and in terms of increase of unemployment or recourse to job-retention scheme. Absent indirect channels of transmission, the aggregation of the views of frontliners may have been less timely.

For all these reasons, women should be better represented in Central Banks. It would also contribute the legitimacy of the institutions in a time when “experts” and “technocrats” are seen as too distant and criticized.

Chart 2: Share of respondents by gender, age group and type of response

Notes: “CSO responses” refers to responses that were copy-pasted from contributions offered by organisations such as Greenpeace. “Original responses” refers to the remaining responses. Source: ECB

3. Why promoting diversity in central bank governance?

There is of course a legal argument for gender equality that is written in the goals assigned to the EU and in national laws. But there are arguments beyond the legal aspect that I want to bring to the discussion.

As already suggested above, the mere existence (and success) of monetary policy committees is to pool knowledge and bring a diversity of views and perspectives to the table. Gender imbalance at the top deprives these bodies of the increase in the quality of knowledge needed to make informed policy decisions, and this may push some given concern to the background. Because monetary decisions arise from the deliberation and vote of a committee of human beings, the relative weight given to the various relevant concerns is necessarily a product of the mix of talents and concerns of the humans assembled around the table.

Yet the impact of gender on the quality of the decisions of a committee is hard to measure objectively because it is difficult to disentangle the impact of gender from the other personal or professional characteristics of women versus men. Research is also more than scarce on the matter, partly because very few women have been in the position to decide on monetary policy.

Recent research is however insightful to discuss the issue at stake. In finance, it is now common to find that more diverse boards in terms of gender is associated with better bank performance, better monitoring of bank managers and therefore lower agency costs (Cardillo et al. 2020). There is also a strong positive association between the share of women in senior positions and firms performance (Christiansen et al. 2016).

In terms of monetary policy outcomes, research have mostly wondered whether women had a stance more dovish – i.e. more in favor of fighting unemployment than inflation – or hawkish – i.e. whether they were more inclined to use the interest rate policy to drive the inflation rate. In a large sample of countries, Masciandaro, Profeta and Romelli (2020) have found that central bank boards with relatively more gender-balanced have tended to push monetary-policy committee towards setting more hawkish policies. By construction, those results do not control for the mandate assigned to the central bank. When focused only on the US history, a recent research conducted at Banque de France have shown that female FOMC members were mostly on the dovish side while men were more hawkish (Istrefi, 2019).

But are women intrinsically more dovish or hawkish than men? Not necessarily as Istrefi and Bordo (2018) have shown. They rather advocate that three main factors have shaped the type of FOMC members. First, the type of economic events they have experienced at birth: FOMC members born during the Great Depression of the 1930s were more inclined to fight unemployment than FOMC members born during the Great Inflation of the 1960s and 1970s. The second factor that influenced the stance of the FOMC member is the economic ideology of their Alma Mater: Having graduated from Chicago University is more likely to make a member hawkish than having graduated from Harvard University. The third important factor is the political affiliation of the US president who appointed them.

Bringing more diversity around a table is therefore not only ethic and legal imperatives, it also doubles the pool of talents. To paraphrase Margarita Delgado Deputy Governor of the Banco de España, “we cannot let 50% of our talent go to waste”.5

As communication is de facto a monetary policy tool as illustrated by the importance of Forward Guidance in managing future economic outlook, and given that communication must be directed towards the general public, and not only the experts, the place of women in monetary policy decision must be a renewed and increasing priority for central banks.

Central banks will succeed in their attempts to reach out with the wider public if they can connect, listen and build common understanding using innovative communication means. This will require an active listening of the registry of words that have the greatest impact on agents’ expectations. If the formation of expectations differs across types, history or gender, central banks will have to experience a revolution in terms of the wording and means of communication they use with the public. This will likely require bringing parity to the decision-making table and to bring more diversity (in general, beyond gender) in the process of aggregating information to be able to take into account the diversity of economic beliefs and expectations. In return, this will strengthen central bank credibility in public eyes, and rebuild trust, thus making monetary policy more effective.

Conclusions

This paper starts with an old paradox. The world of decision-makers is still a man’s world but women are mainly in charge of crucial and vital economic tasks in our societies and households. Yet their economic concern and the way they form expectations are at first glance different from those of men, maybe mostly because of different life history, level of education and occupations. Does that makes a difference, even from a central banker point of view? It may well, notably through the channel of the way women react to the communication of central banks, which feedback on the communication central banks must adopt to be more effective in the transmission of their monetary policy. Yet it is not only gender per se that matters but the fact that decisions are better informed when diverse point of views are represented around the table, in all and every dimension of diversity. Greater diversity at the top will make the world a better place to live in. And it would be fairer.

Arnold, Martin and Daniel Dombey, 2021, Women central bankers want action on ‘hidden barriers’ to equality, Financial Times published 4th of May.

Bagehot, Walter, 1873, Lombard Street: A description of the money market London: Henry S. King & Co.

Bernanke, Ben S., 2004, Gradualism, Remarks at an economics luncheon co-sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (Seattle Branch) and the University of Washington, Seattle, 20 May.

Cardillo, Giovanni, Enrico Onali, Giuseppe Torluccio, 2020, Does gender diversity on banks’ boards matter? Evidence from public bailouts, Journal of Corporate Finance forthcoming.

Christiansen, Lone, Engbo, Huidan Lin, Joana Pereira, Petia Topalova, and Rima Turk, 2016, Gender Diversity in Senior Positions and Firm Performance: Evidence from Europe, IMF Working Paper WP/16/50.

van Daalen KR, Bajnoczki C, Chowdhury M, et al., 2020, Symptoms of a broken system: the gender gaps in COVID19 decision-making, BMJ Global Health.

Eggertsson, Gauti B. and Michael Woodford, 2003, The Zero Bound on Interest Rates and Optimal Monetary Policy, Brooking Papers on Economic Activity 33(1).

European Commission, 2021 report on gender equality in the EU, 2021.

Friedman, Milton and Anna J. Schwartz, 1963, A monetary history of the United States 1867-1960, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gaballo, Gaetano, 2016, Rational inattention to news: The perils of Forward Guidance, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 8(1), p. 42-97.

Hansen, Lars Peter, and Thomas J. Sargent, 2001, Robust Control and Model Uncertainty American Economic Review, 91 (2), p. 60-66.

Krugman, Paul, 1998, It’s Baaaack! Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 28(2): 137–87.

Istrefi Klodiana and Michael D. Bordo, 2018, Perceived FOMC: the Making of Hawks, Doves and Swingers, Banque de France Working Paper #683.

Istrefi, Klodiana and Giulia Sestieri, 2018, Central banking at the top: it’s a man’s world, Banque de France blog, with data updated to 2021.

Istrefi Klodiana, 2019, In Fed Watchers’ Eyes: Hawks, Doves and Monetary Policy, Banque de France Working Paper #725.

Masciandaro, Donato and Paola Profeta and Davide Romelli, 2020. Do Women Matter in Monetary Policy Boards? BAFFI CAREFIN Working Papers 20148, Universita’ Bocconi.

Morris, Stephen and Hyun Song Shin, 2002, Social Value of Public Information American Economic Review 92(5), p. 1521–34.

See the 2021 report on gender equality in the EU .

Source: van Daalen et al. (2020).