If the corona pandemic makes one thing clear, it is that not everything can be captured in models and figures. Yet, we can still distinguish some trends that are accelerating due to the covid-19 crisis. In addition, we can point out a number of new developments that arise from the pandemic and its aftermath. Governments are likely to seek refuge in raising public deficits to far higher levels and have them financed by central banks. This is not a sustainable solution, as stagflation will soon become a risk here. However, developments seem to be heading in this direction in the end, and it therefore looks as though interest rates will rise substantially in the longer term. Gold and other inflation hedges will benefit in this climate.

Flattening contamination curves, incubation times, serological tests… We have all become self-proclaimed virologists and epidemiologists. This is not very surprising. The vast majority of people become very restless due to great uncertainty. This is why, in a situation such as the corona crisis, we try to get a grip on unpredictability by holding on to assumed certainties and hard data.

If the pandemic makes one thing clear, it is that not everything can be captured in models and figures. Former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King and economist John Kay argue in their book Radical Uncertainty that a clear distinction should be made between risk and uncertainty.

Famous economists such as John Maynard Keynes and Frank Knight did this very explicitly. In short, they stated that risks can be measured, and that uncertainty cannot be measured. Renowned colleague Milton Friedman disliked this distinction; according to him, uncertainties were little more than risks that were not yet well defined. He literally said about the difference between risk and uncertainty: “I have not referred to this distinction because I do not believe it is valid. We may treat people as if they assigned numerical probabilities to every conceivable event.”

This mindset largely underpinned the financial and economic crisis of over a decade ago. Many believed that, with ever more and increasingly complex financial instruments, we had entered a world where uncertainty had been tamed by putting a price on every conceivable risk. Until it turned out that mortgages considered to be completely safe were not that safe after all.

Widely regarded as the first domino in the credit crisis, Northern Rock was one of the banks with the strongest capital reserves in 2007. At that time, mortgages were still considered to be entirely safe and problems on the funding side were not considered at all. Things certainly can change…

The corona crisis is an even bigger shock to people who believe that they can capture everything in models and data. While the risk of a pandemic has been on global economic risk lists for many years in surveys among CEOs, economists and scientists, no-one knew when and how it would happen and what the exact impact would be.

Analysts at the major banks and asset managers also basically admit this, as they have indicated in recent weeks that their models fall short in this crisis. They had not thought of a model in which governments would deliberately trigger a recession by paralysing substantial parts of the economy. No model was conceived for the possibility of the number of applications for unemployment benefits in the US increasing sixfold compared to the former record of 1982. It will therefore be very complex to predict with any accuracy how markets and economic growth will develop in the coming quarters.

This (re)new(ed) sense of radical uncertainty – as Kay and King call it – will take hold of society and the economy long after the pandemic is under control. For example, companies will strive for more resilience and robustness and keeping more options open in their processes. This also means that logistics principles such as Just In Time – which were considered sacred until recently – may no longer be relevant before too long.

In recent decades – also after the Great Recession (which may need to be renamed after the corona crisis) – administrators have often been enamoured of people who claimed to be able to capture everything in spreadsheets and provided a feeling of almost total control. When the worst of the pandemic is over, it will hopefully be realised that it is sometimes better and far less risky to dare to say ’I don’t know’ rather than to try and predict something at any cost, when this prediction is riddled with uncertainty.

However, as a company and investor you cannot say: “There are many things we do not know, which is why the uncertainty is too great and therefore we do not invest.” Making plans in an inherently uncertain future simply requires that you take certain uncertainties for granted and factor in definable risks for making responsible investment decisions.

One of the biggest risks is that people generally tend to extrapolate. For example, the longer things go well, the more positive the expectations for the future, where the risk of things going awry is considered to be (too) low. As a result, bigger risks are taken, which increases the vulnerability to unexpected shocks. This is evident at all levels, among individuals, companies and governments.

The corona crisis probably means that companies and investors are generally likely to stretch the range of possible scenarios with which they work. They will still want to exclude risks in the sense of threats as far as possible, but a certain degree of uncertainty should be recognised as unavoidable. Incidentally, uncertainty is not good or bad; things could still go both ways.

More specifically, we still do not know much with 100% certainty about the coronavirus, including how deadly or infectious it is, how exactly the virus is transmitted, whether the virus is sensitive to warmer weather, how many people have been infected, and if and when a vaccine is available, et cetera. Regarding the latter, the following is a sobering comment on all the optimistic stories of impending treatment methods and vaccines: in the US, 90% of all vaccines that made it to clinical trials proved unsuitable for humans.

In addition, there are very painful examples of vaccines that were used too soon or where production went awry with disastrous results. One of the best-known examples dates back to 1955 when 200,000 people were accidentally vaccinated with an agent that contained an active form of the poliovirus. Tens of thousands fell ill, many suffered permanent paralysis, and several children died.

A renowned medical scientist recently warned that the whole world is pretending that we largely understand the coronavirus, when we only discovered the virus a few months ago and it sometimes took years before we understood other viruses. Therefore, when reading news reports – and certainly stories like Trump’s statements about new medicines and vaccines – realise that correlations do not have to be causal connections and that anecdotes are not data.

Ultimately, economies will only be able to run at full speed again – if at all – via (a combination of) three solutions:

All three escape routes are still foggy and dimly lit, so for now we have to make do with occasionally illuminated signposts. Looking at past medicine and vaccine developments, some of the much-hoped-for resources will undoubtedly disappoint. On the upside, it has probably never before been attempted on a such a great scale to suppress a disease, and the virus has similarities with previous viruses; and this is why research does not have to be started from scratch. For the time being, the most likely scenario – which is surrounded by all manner of uncertainties – is that we will at least still be faced with restrictive measures in the coming year, which will be tightened or weakened as and when the virus emerges.

Although we now realise more than ever how much we do not know and we live in a new world of a heightened sense of risk and uncertainty awareness, we can still distinguish some trends that are accelerating due to the corona crisis. In addition, we can point out a number of new developments that arise from the crisis and its aftermath.

From a political perspective, the direction in which countries will be moving in the wake of the crisis is not certain. At this point, incumbent governments are generally doing very well in the polls. This is in large part due to the ‘rally around the flag’ effect where citizens believe that now is not the time to protest against the government and choose to rally behind their political leaders. To some extent, this is even evident in the US, where ratings for President Trump – despite his lamentable approach – are at record levels; although this record isn’t much too boost about, standing at 46-47%…

In any event, if, during and after the crisis, the emphasis is placed on solidarity and cooperation that is required within and between countries, the moderate centre parties could do very well. David Brooks put it this way: “The moral story we tell has to be less about the evil we face and more about the solidarity we are building with one another. The story we tell has to be about how we took this disease and turned it into an occasion to become a better society.”

In addition, it is quite possible that left-wing politicians are more successful than right-wing politicians, since the current predicament has demonstrated the importance of a government that can adopt a large-scale, consistent and coherent approach and can protect its citizens against dangers and setbacks that businesses are unable to cope with. If people start appreciating more government intervention, they will also express this attitude in their voting behaviour. By the way, looking at the past, we usually see a pendulum movement between market forces and a more government-driven economy and a correction of out-of-control market thinking seemed to have been underway for some time.

This pendulum movement could have an unpleasant aftertaste if the emphasis is placed on a war against great evil and a danger that emerges from beyond one’s borders. If this sentiment prevails, protectionist, isolationist populists could gain momentum again. For the time being, populists in most of Europe have been on the defensive and in most places they make an extremely vulnerable impression.

We suspect that the ‘big government’s back’ hypothesis will still stand for a while, and that the appreciation of stronger social safety nets will not disappear like snow from the sun when the corona crisis has faded into the background somewhat. Particularly because the economic fall-out will continue for a while and because it is clear that the US welfare state, which is weak compared to Europe, is now a liability for the US. It has often been argued that the relatively basic social security of the US has made its economy far more flexible and innovative.

All this does not mean that it is a piece of cake for the centre parties. The populist parties that have been successful in recent years often plead for a left-wing socio-economic policy and a right-wing socio-cultural and security policy. If moderate politicians go wrong now, these parties could be successful.

In addition, based on historical and evolutionary research, it appears that countries that have experienced major epidemics and many infectious diseases are more inclined towards a collective society and stronger behavioural and normative standards. In addition, these countries often display more intolerance towards deviant behaviour, less innovation, authoritarian leadership, conservative voting behaviour and increased xenophobia.

Naturally, leaders in a number of countries are seizing the moment to strengthen their authoritarian tendencies and further demolish democracy, if any, in the name of the fight against the epidemic. The most striking example is Hungary, where Prime Minister Orban has completely sidelined parliament. This does not have to be directly fatal if it were not for the fact that a clear time frame is lacking in this state of emergency. In other words, it is quite possible that Orban will declare a permanent state of emergency, leaving nothing to fear from judges and parliament.

Many analysts are greatly concerned that many of the measures that are now being put in place to combat COVID-19 are slightly too convenient for politicians and other government officials. And that we will therefore see an accelerated erosion of democracies and freedoms in the coming years (this trend had been evident for more than a decade before the outbreak of the pandemic). The Orwellian surveillance state suddenly seems very close.

One thing is certain: liberal democracy will certainly not rest on its laurels in the coming years. Developments were already underway towards a world with two superpowers – China and the US – with both seeking to gain as many allies as possible through political, economic, cultural and military carrots and sticks, but the corona crisis will force players to make accelerated choices. In doing so, the US is doing no good in the way it deals with the pandemic. In addition, recent surveys show that Chinese citizens believes that it is increasingly less worthwhile to follow the example of the US.

Related to the foregoing is the question as to whether or not the crisis reinforces and accelerates the process of deglobalisation. Due to the credit crunch and increasing inequality, for example, the form of globalisation that had been declared sacred in the 1990s in particular was already under attack. More and more questions will be raised about the unrestrained movement of capital, people, services and goods around the world and the vulnerability to a high dependence on foreign suppliers, financiers and production sites.

It is not black and white in the sense that globalisation ends, but countries, companies and citizens are now scratching their heads. Businesses will steer far less on lowest cost and will focus more on security of supply / production. Governments will want to produce strategic products (such as medicines, medical equipment, food, means of communication, et cetera) domestically. If this is not possible, they will want to build larger stocks. And consumers will become more averse to risk and will save and postpone large purchases for a while.

Production chains will therefore be redesigned in the coming years in order to develop more security and governments will, even more than before, identify sectors and specific companies as essential for national security, protect them from foreign takeovers and keep them afloat with a great deal of public money if required. These developments will increase the cost price and reduce productivity, but this does not necessarily has to be bad if they make the system as a whole more robust.

Increasing restraint and prudence among most economic players seems to be self-evident. At the same time, we have to keep in mind that many believed that this scenario would be evident for a long time after 2008/2009. However, it did not take long before debts started rising very rapidly again. People sometimes underestimate how quickly people revert to their old behaviour once a crisis is over. This is why we will see more excessive forms of risk in the long run, but we still believe that the current calamity is such a major event that it could leave more lasting marks than the credit crunch. This is because this crisis directly affects the entire fabric of a society, no one is spared the consequences and it is literally and directly a matter of life and death.

How to translate the corona crisis and the resulting/accelerated larger trends for the markets in an uncertain time in which the so-called leader of the free world sometimes seems to rely more on anecdotes than on data?

Global economic growth is likely to be structurally lower following an upturn once the pandemic has subsided somewhat because production chains have built in more slack at the expense of efficiency. Moreover, this coincides with the further restriction of globalisation and generally more risk-averse behaviour. In addition, the corona crisis has brought the geopolitical fault lines to the surface even more, which is likely to lead to tensions between the US and China. In addition, governments should take over a far larger part of the economy if both consumers and businesses cut down on expenditure. This usually results in lower productivity.

In the somewhat shorter term, countries that have taken social distancing measures relatively late will generally be the worst off, as evidenced by studies into previous epidemics. During the Spanish flu in 1918, for example, US cities that announced strict measures had fewer victims and these cities showed a far stronger economic recovery than the laxer cities. This is one of the reasons why the recovery in Europe is likely to come sooner than in the US, and it will be more forceful. One could criticize the approach to the crisis in some European countries, but their approach is usually a relief compared to how things have sometimes panned out in the US in recent weeks. In addition, the US is likely to have a public deficit of 15% of GDP this year.

Within Europe, Germany in particular seems to have good opportunities to stand out once an upturn becomes evident before long. This is partly due to the very high number of hospital (and IC) beds per 100,000 inhabitants, the many tests that Germany is carrying out and its healthy public finances.

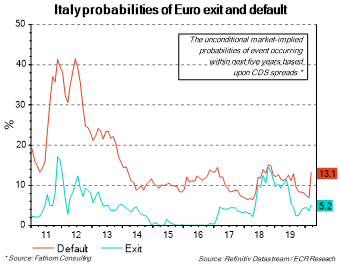

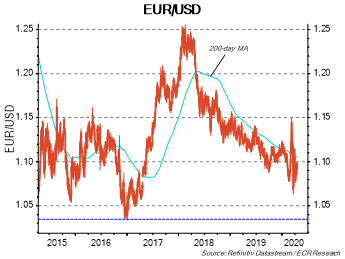

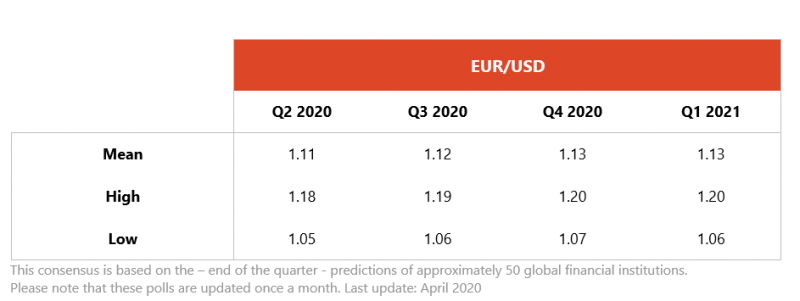

In view of the above, the euro is likely to strengthen significantly against the dollar in the coming quarters. Unless the northern European countries abandon Italy and the Eurozone is in jeopardy again.

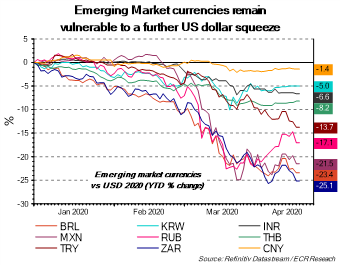

The coronavirus is only beginning to wreak havoc now in many emerging and developing countries. Investors would do well to be very careful in terms of investing in this group of economies for the time being due to their generally very weak healthcare systems, poor governance, large dollar loans, far worse options in terms of social distancing, their dependence on tourism and/or (oil) exports and existing political tensions. Specifically, we would keep a close eye on Brazil and Mexico – relatively open economies that buried their heads in the sand far too long when it comes to corona and which rely greatly on oil and tourism.

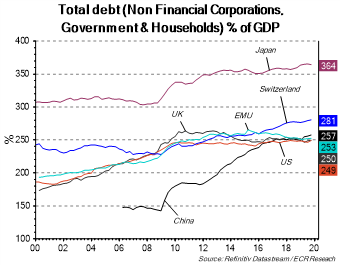

In any case, debts of many companies and governments will rise considerably. Certainly against the background of an ageing population, as a result of which expenditure on health care and pensions will rise considerably. This means that once the situation has normalized to an extent, the recovery will be slowed down because efforts will have to be geared towards debt reduction.

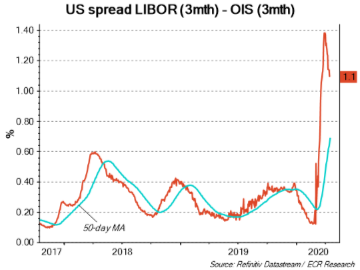

In addition, companies and individuals who want to borrow will be faced with reluctance among banks and other credit suppliers, due to, among other things, far higher bankruptcy risks and uncertainty about the extent to which economies have been permanently disrupted.

Low growth and high debt usually lead to deflation. Deflation is very risky, as the soaring debts will weigh even more heavily in this case. Governments are therefore likely to seek refuge in raising public deficits to far higher levels and have them financed by central banks. This is not a sustainable solution, as stagflation will soon become a risk here. However, developments seem to be heading in this direction in the end, and it therefore looks as though interest rates will rise substantially in the longer term. Gold and other inflation hedges will benefit in this climate.

In any case, the financial markets and the global economy are most likely in for a protracted rough patch considering the unpredictable and dangerous combination of a pandemic that is far from over (with an uncertain outlook when it comes to vaccines and medicines), a slowing of and reconfiguration of globalisation, a strengthening of authoritarian tendencies, a comeback of big government and rising, unsustainable debt levels.

This policy note originally appeared as Global Political Risks publication on the research platforms of ECR Research and ICC Consultants.