This policy brief is based on an article published in OeNB Bulletin Q3/25. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions the authors are affiliated with.

Abstract

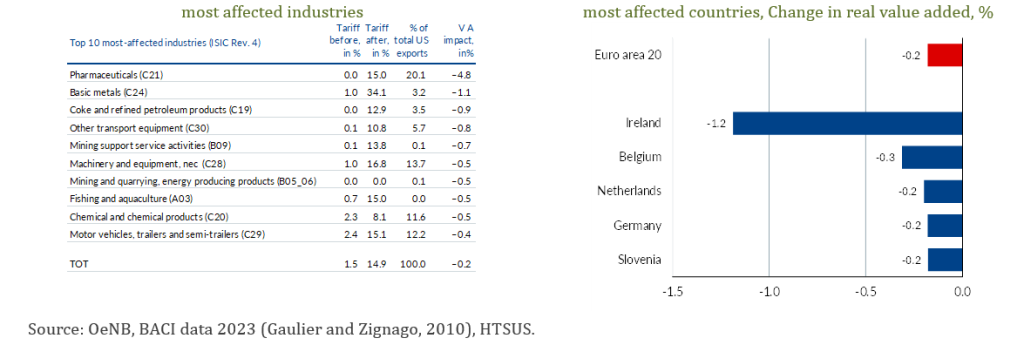

This policy brief assesses the medium-term effects of new US tariffs imposed in 2025, simulating the US-EU trade deal of July 27 for the euro area countries and their industries using a global input-output model. Results show EA-20 value-added declining by 0.2% in the short-term, up to 0.5% after 10 years, with varied effects across sectors and countries. Pharmaceuticals, basic metals and coke and refined petroleum products are most affected, while Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany face the largest country-level value-added losses. The policy brief also evaluates implications for policy and resilience strategies.

On president Trumps inauguration day January 20, the White House released a memorandum on its trade priorities, instructing several departments and agencies to undertake reviews of unfair trade practices by April 1.1 In February and March Trump started imposing tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China officially on the grounds of combatting fentanyl trafficking. Furthermore, Trump issued several presidential orders imposing import tariffs of 25% on steel, aluminum, copper, automobiles and automobile parts against all countries on national security grounds. Some of these were later increased to 50%. The trade war then fully escalated when Trump announced tariff against nearly all countries and a large range of products on April 2nd. These tariffs were justified by invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). To combat the bilateral US trade deficits that constitute the emergency, the initial tariff of 10% against all countries should increase to higher country-specific rates based on the size of the bilateral deficit by April 9th. The additional tariff rate for non-exempted products from EU countries would amount to 20%, while China would face an additional 34%. Following huge losses in the US stock market, Trump paused this increase for 90 days in which several countries brokered bilateral trade deals with the US.

On July 27 the president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen and Donald Trump agreed on a US-EU trade deal. According to the deal the US import tariffs on products entering from EU countries would still be an additional 50% for steel, aluminum and copper but for all other non-exempted products the tariff would be set to 15%. This includes products where the EU has high export shares to the US such as automobiles, automobile parts and pharmaceuticals. In return, some products such as unavailable natural resources, all aircraft and aircraft parts, generic pharmaceuticals and their ingredients and chemical precursors have been exempted. Furthermore, the EU agreed to buy LNG for 750 billion USD, to invest 600 billion USD in the US and to reduce/abandon tariffs on US automobiles and agricultural products.

In this policy brief, we bring an update of the results shown outlined in Schneider and Sellner (2025). Our analysis here will cover the impact of all US-tariffs vis-à-vis the EU2 introduced between January 20 and August 6 of 2025 on the industries of the euro area countries. This includes the additional 50% tariff rate on steel, iron, aluminum and copper and the flat rate of 15% agreed in the US-EU trade deal on all other non-exempted products including automobiles, automobile parts and pharmaceuticals. Exempted products include among other aircraft and aircraft parts and critical products such as specific energy sources, chemicals and semi-conductors.

We simulate the effects of the tariffs on value-added (VA) of the industries of the euro area countries in two steps.

First, we derive the decrease in US imports due to the tariffs for each partner country at a detailed product level. The decrease in imports is given by the tariff change at the product level multiplied by the tariff elasticity. We gathered product level tariff data from the US harmonized tariff schedule.3 The tariff elasticities are based on the long-term estimates of Fontagné et al. (2022), which are available at a detailed HS 3 6-digit product level (5,052 products). They range between –3.6 for highly differentiated products like footwear to –19 for standardized products like mineral products. An elasticity of i.e. –4 would imply that an increase in the tariff rate of 25% leads to a reduction in imports of 100%. Before applying these product-level elasticities we thus need to adjust them to reflect more plausible sizes for short- to medium-term impacts. We do this by re-scaling them such that the mean trade-volume-weighted US import tariff elasticity yields the causal estimates of Boehm et al. (2023), which are –0.76 after one year, –1.24 after 5 years and –2.12 after 10 years.

In a second step, we match the import decrease at the product level to the 45 ISIC Rev.4 sectors of our global input-output model which is based on the OECD’s global input-output table for 2019.4 We then feed this demand shock into the model which captures both the direct trade effects on targeted industries and the indirect repercussions transmitted through international production networks. As a result, we obtain the effects on output and value added per country and industry. Further details can be found in Schneider and Sellner (2025).

In the following we will focus on the short-term (one year after tariff increase) VA impacts which are also depicted in Figure 1.

The industry results show that pharmaceuticals stand out as the single most affected sector. Increasing the tariff rate to 15 % on these products would reduce VA in pharmaceutical manufacturing of the euro area by 4.8 %. This is because pharmaceuticals account for a fifth of all euro area goods exports to the US. The most severe decreases in VA in pharmaceuticals are expected to materialize in Ireland (–9.8 %), Belgium (–4.7 %) and the Netherlands (–3.2 %).5 The industry with the second highest VA loss is manufacture of basic metals (–1.1 %). While these products account only for roughly 3 % of total EA goods exports to the US, the average tariff rate of this industry will increase from 1 % to 34 %. The euro area results for this industry are driven by the VA impacts on basic metals in Germany (–1.1 %).

Figure 1. Short-term production network effects of US-EU trade agreement on EA-20 value added (VA)

The results by country reveal that total economy value added in Ireland will be most affected (–1.2%), given the prominent role of their pharmaceutical industry with its high export exposure to the US. The US-tariff impacts for the other euro area countries are much smaller and much closer to each other. Besides Ireland, the strongest impacts of the US tariffs are expected for Belgium (–0.3%), the Netherlands (–0.2%) and Germany (–0.2 %). Like in Ireland, the pharmaceutical industry is hit hardest by the tariffs in those countries.

We have retrieved the 5-year and 10-year impacts by multiplying the short-term results from above with the 5 resp. 10 year elasticities relative to the 1 year elasticity of Boehm et al. (2023). For the euro area, the negative impact value added rises from –0.2% after one year to –0.3% after 5 years and to ‑0.5% 10 years after the tariff increase.6 Our aggregate results for the EA – although not accurately comparable due to different scenario assumptions and underlying models – are in line with recent studies from Bruegel, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy and the European Commission (Barata de Rocha et al. (2025), Hinz et al. (2025) and European Commission (2025)).

The strength of our approach is that it produces results at a very disaggregated level. While Trumps trade policy is highly erratic, it is also oddly specific in that it targets and includes products at a very detailed product level. Our approach provides a plausible figure of tariff exposure given the specific products countries trade with the US and the underlying global production network of those products.

However, there are some caveats to consider when interpreting the results. Our input-output model is static and does not feature equilibrium adjustments, second round effects and monetary or fiscal policy reactions. It also cannot account for indirect effects such as trade and investment diversion, longer-term supply chain re-orientation, or the intensification of policy uncertainty. Evidence from recent years shows that elevated uncertainty tends to suppress business investment and household consumption, thereby amplifying the short-run burden of trade shocks.

The dynamic evolution of EU-US trade relations since 2019 poses another important challenge. Since then, EU exports to the US have risen considerably, with pharmaceutical shipments nearly doubling in value over five years. This means the model’s results may understate the real economic impact for countries and sectors where the US has become a more important destination. In addition, exclusion of potential retaliatory measures or collateral consequences—for example, volatility in the financial sector—suggests the potential for even larger downside risks to euro area growth.

Despite these caveats, there are some important policy conclusions that can be drawn from our analysis. First and foremost, the negative impact in the euro area is not negligible but manageable. However, certain industries (especially, manufacture of pharmaceuticals) might suffer considerably. In the short term, ongoing diplomatic initiatives to address trade disputes and to negotiate potential tariff reductions are essential for curbing further escalation dynamics. Furthermore, providing targeted support to highly exposed industries might be necessary. In the medium term, the EU should strengthen its efforts to diversify export markets, to reduce reliance on the US and to increase resilience against unilateral tariffs. In addition, enhancing integration of the EU internal market and improving the resilience of European supply chains can help cushion the effects of external trade shocks. These policy actions can help mitigate the negative ramifications of US tariffs and promote sustainable economic growth in the EU.

Barata da Rocha, M., N. Boivin and N. Poitiers. 2025. The economic impact of Trump’s tariffs on Europe: an initial assessment. Bruegel Analysis. April 17, 2025.

Boehm, C., A. A. Levchenko and N. Pandalai-Nayar. 2023. The long and short (run) of trade elasticities. In: American Economic Review 113 (4): 861–905.

European Commission. 2025. The macroeconomic effect of US tariff hikes. Special topic of the Spring 2025 economic forecast. May 19, 2025. The macroeconomic effect of US tariff hikes – European Commission.

Fontagné, L., H. Guimbard and G. Orefice. 2022. Tariff-based product-level trade elasticities. In: Journal of International Economics 137: 1–25.

Hinz, J., I. Méjean and M. Schularick. 2025. The consequences of the Trump trade war for Europe. Kiel Policy Brief No. 190. April 2025.

Schneider, M., and R. Sellner. 2025. The impact of US tariffs on EU industries: results from a global input-output model. OeNB Bulletin Q3 25, 23-47.

For a summary of all important escalations of the US trade war including the links to the relevant documents see Trump’s trade war timeline 2.0: An up-to-date guide | PIIE.

Hence, we do not consider the US-tariffs against other countries, in particular China, Canada and Mexico, as well as retaliatory tariffs (i.e. from China).

We used 2025 HTS Revision 18 of August 6, 2025 from https://hts.usitc.gov/download/archive

See https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/inter-country-input-output-tables.html. The model contains 76 countries and a region capturing the rest of the world.

Industry results by country are available from authors upon request.

Note that values are rounded to one digit.